The Late Cretaceous period, spanning from about 100 to 66 million years ago, represents one of the most dramatic chapters in Earth’s history. While Tyrannosaurus rex commands the spotlight in popular culture, this ancient world teemed with an incredible diversity of predators that would make today’s apex hunters look like house cats. From the razor-clawed Utahraptor to the crocodilian giants lurking in primordial swamps, the Late Cretaceous was a time when being a herbivore meant living on borrowed time. These weren’t just oversized lizards stumbling around a prehistoric landscape – they were sophisticated killing machines, each perfectly adapted to their ecological niche, employing hunting strategies that would make modern predators envious.

The Dracorex: When Dragons Walked the Earth

Imagine discovering a skull so perfectly dragon-like that paleontologists couldn’t resist naming it after the Harry Potter series. Dracorex hogwartsia, literally meaning “dragon king of Hogwarts,” represents one of the most captivating discoveries in recent paleontology. This smaller relative of Pachycephalosaurus possessed a skull adorned with spikes and knobs that would make any medieval artist proud.

What makes Dracorex particularly fascinating isn’t just its mythical appearance, but its potential role as a juvenile form of larger pachycephalosaurs. The creature’s skull features tell a story of evolutionary adaptation that challenges our understanding of dinosaur development. Some scientists believe Dracorex might actually represent the teenage phase of Pachycephalosaurus, similar to how a tadpole transforms into a frog.

The discovery of Dracorex in South Dakota’s Hell Creek Formation opened new discussions about dinosaur classification and growth patterns. These weren’t massive predators, but their unique skull structure suggests they had their own specialized feeding strategies and social behaviors that set them apart from other herbivorous dinosaurs of their time.

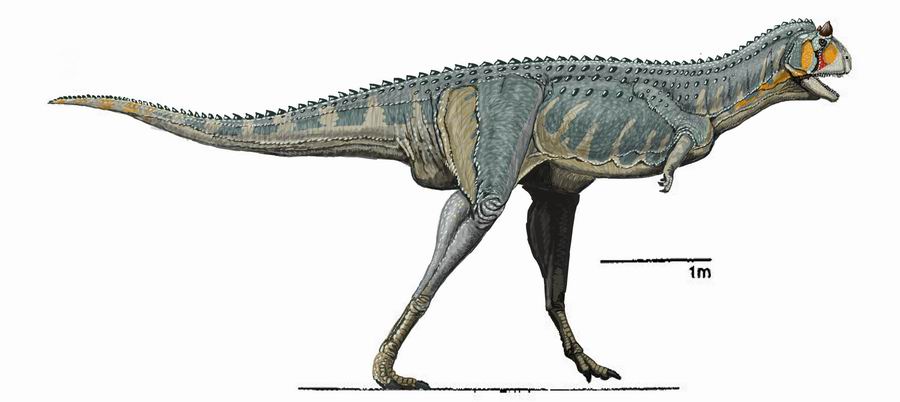

Carnotaurus: The Meat-Eating Bull

Picture a two-ton predator sprinting across the South American plains at speeds that would shame a racehorse. Carnotaurus sastrei, the “meat-eating bull,” represents one of evolution’s most specialized experiments in predatory design. With forward-facing horns jutting from its skull and eyes positioned for stereoscopic vision, this dinosaur was built for one purpose: high-speed pursuit of prey.

Unlike the heavily muscled arms of its distant relative Tyrannosaurus, Carnotaurus took arm reduction to an extreme that seems almost comical today. Its forelimbs were mere stubs, so reduced they lacked elbows entirely. This might seem like a disadvantage, but it actually reveals something remarkable about this predator’s hunting strategy – it relied entirely on its powerful legs and devastating bite.

The discovery of Carnotaurus skin impressions provides unprecedented insight into how these predators might have appeared in life. The fossilized skin shows small, pebbly scales arranged in rows, similar to modern crocodiles but adapted for a life of constant motion. This wasn’t a slow, lumbering giant but a precision-engineered pursuit predator that could run down prey across open landscapes.

Giganotosaurus: The True Giant

When paleontologists first unearthed Giganotosaurus carolinii in Argentina, they realized they had found something that challenged T. rex’s throne as the ultimate predator. This South American giant stretched up to 43 feet in length and may have outweighed even the largest Tyrannosaurus specimens. But size wasn’t its only advantage – Giganotosaurus possessed a skull designed for slicing rather than crushing.

The teeth of Giganotosaurus tell a different story than those of T. rex. While Tyrannosaurus evolved banana-shaped teeth for bone-crushing bites, Giganotosaurus developed blade-like teeth perfect for slicing through flesh. This suggests fundamentally different hunting strategies – where T. rex might have been an ambush predator capable of delivering devastating single bites, Giganotosaurus was likely a more active hunter that relied on blood loss to bring down prey.

Living alongside the massive sauropod Argentinosaurus, Giganotosaurus may have been part of cooperative hunting groups. The idea of pack-hunting giants sounds like science fiction, but evidence suggests these predators might have worked together to bring down prey that would have been impossible for a single individual to tackle.

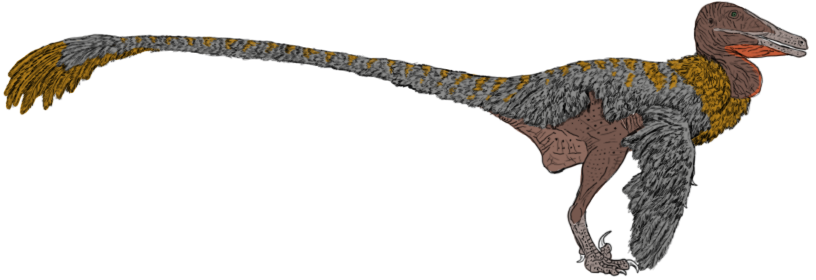

Utahraptor: The Ultimate Sickle-Claw

If Velociraptor was a deadly kitchen knife, then Utahraptor ostrommaysi was a medieval battle axe. This North American predator represents the pinnacle of dromaeosaurid evolution, combining the intelligence and agility of smaller raptors with the size and power of much larger predators. Standing nearly 6 feet tall at the hip and measuring up to 20 feet in length, Utahraptor was large enough to hunt even the biggest herbivores of its time.

The signature weapon of Utahraptor was its massive sickle-shaped claw, measuring up to 15 inches in length. This wasn’t just for show – biomechanical studies suggest these claws could deliver devastating puncture wounds that would cause rapid blood loss in prey. The hunting strategy likely involved leaping onto large herbivores and using these claws like climbing hooks while smaller pack members attacked from below.

Recent discoveries have revealed that Utahraptor, like many of its smaller relatives, was likely covered in feathers. This creates an almost surreal image – a giant, feathered predator equipped with switchblade claws, hunting in the forests of ancient Utah. The intelligence required to coordinate such complex hunting strategies suggests these weren’t just mindless killing machines, but sophisticated predators capable of problem-solving and social cooperation.

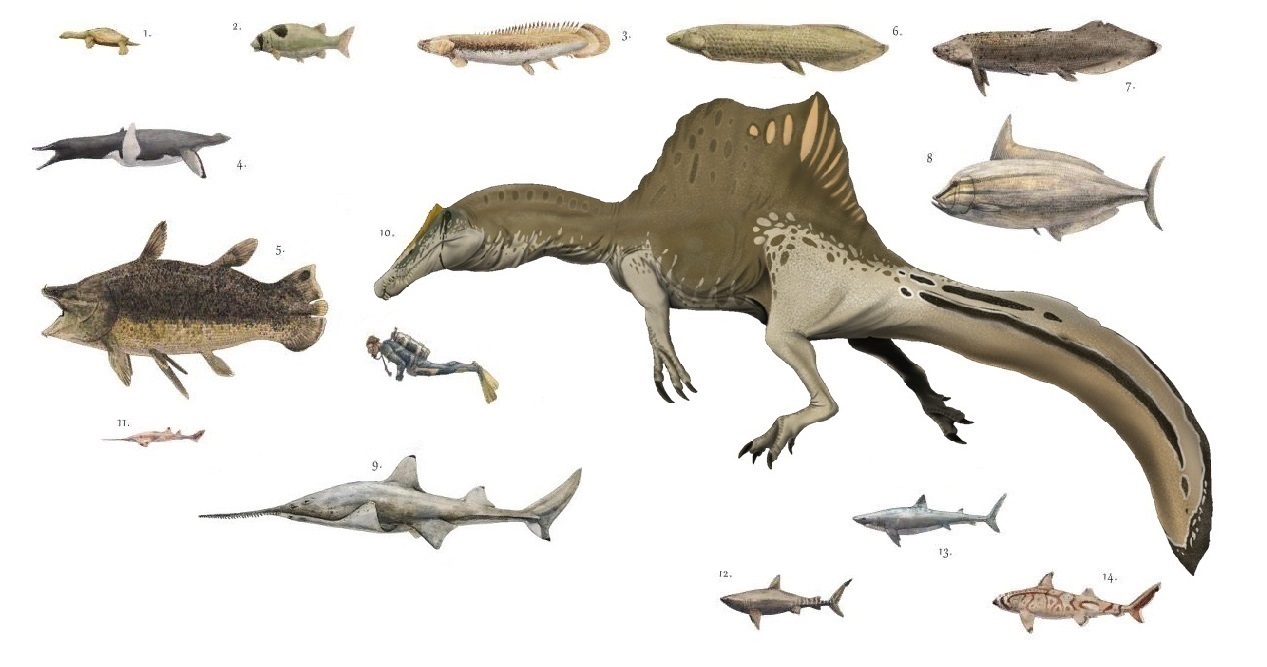

Spinosaurus: The River Monster

Long before crocodiles ruled the waterways, Spinosaurus aegyptiacus dominated the river systems of ancient Africa. This semi-aquatic giant represents one of the most unusual predatory dinosaurs ever discovered, with adaptations that seem almost alien compared to typical theropods. The massive sail on its back wasn’t just for temperature regulation – it may have been a display structure used for communication with other Spinosaurus individuals.

Recent discoveries have revolutionized our understanding of Spinosaurus anatomy and behavior. The paddle-like tail, dense bones for underwater navigation, and elongated skull filled with conical teeth all point to a lifestyle more similar to modern crocodiles than to terrestrial dinosaurs. This wasn’t a land predator that occasionally fished – it was a fully aquatic hunter that spent most of its time in the water.

The ecological niche occupied by Spinosaurus had no real equivalent in the modern world. Imagine a predator larger than T. rex, but designed for aquatic hunting, capable of pursuing large fish and even small dinosaurs that came to drink at the water’s edge. This semi-aquatic lifestyle allowed Spinosaurus to avoid direct competition with other large predators while exploiting a rich food source that most dinosaurs couldn’t access.

Allosaurus: The Persistent Predator

While technically reaching its peak during the Late Jurassic, Allosaurus fragilis continued to terrorize prey well into the Early Cretaceous, making it one of the most successful predatory dinosaur genera in history. This medium-sized theropod, measuring up to 28 feet in length, developed a hunting strategy based on persistence and opportunism that kept it competitive even as larger predators evolved around it.

The skull of Allosaurus reveals a predator designed for versatility rather than specialization. Its teeth were sharp but not overly large, its bite force was moderate but sufficient, and its body was built for sustained activity rather than explosive power. This jack-of-all-trades approach allowed Allosaurus to exploit a wide variety of prey and hunting opportunities.

Evidence suggests that Allosaurus may have been one of the first dinosaurs to develop pack hunting behaviors. Fossil sites containing multiple individuals of different ages suggest these predators may have lived and hunted in family groups, with juveniles learning hunting techniques from adults. This social structure could explain how Allosaurus remained successful for so long despite competition from larger and more specialized predators.

Mapusaurus: The Pack Hunter

In the badlands of Argentina, paleontologists uncovered evidence of something that would have been absolutely terrifying to witness – a pack of giant predators hunting together. Mapusaurus roseae, closely related to Giganotosaurus, represents one of the clearest examples of cooperative hunting behavior among large theropod dinosaurs. Multiple individuals found together suggest these 40-foot predators worked as a team to bring down the largest prey animals of their time.

The discovery of Mapusaurus fossils in a bone bed containing individuals of different ages provides compelling evidence for complex social behavior. Unlike modern pack hunters like wolves, these weren’t small, agile predators – they were multi-ton killing machines that somehow coordinated their attacks. The logistics of such cooperation boggles the mind when you consider the size and power of these animals.

Living alongside Argentinosaurus, the largest land animal ever discovered, Mapusaurus faced prey that would have been impossible for any single predator to kill. The evidence suggests these predators developed sophisticated hunting strategies that involved coordinated attacks, with different individuals playing different roles in bringing down massive sauropods. This level of cooperation requires intelligence and communication skills that rival modern mammals.

Carcharodontosaurus: The Shark-Toothed Giant

In the scorching deserts of what is now North Africa, Carcharodontosaurus saharicus ruled as the apex predator of its ecosystem. Named for its resemblance to great white shark teeth, this massive theropod developed one of the most efficient slicing mechanisms in the dinosaur world. Its skull, measuring up to 5 feet in length, was filled with serrated teeth designed to tear through flesh with surgical precision.

The hunting grounds of Carcharodontosaurus were unlike anything in the modern world. Ancient Africa was a lush, tropical environment filled with massive sauropods, heavily armored fish, and crocodilians that would dwarf today’s largest specimens. In this competitive environment, Carcharodontosaurus evolved to be not just large, but incredibly efficient at processing prey.

Biomechanical studies of Carcharodontosaurus skull structure reveal a predator optimized for rapid feeding. The relatively narrow skull and sharp teeth suggest a feeding strategy focused on quick, deep wounds that would cause rapid blood loss. This approach would have been particularly effective against large prey animals that couldn’t be killed quickly through crushing bites alone.

Majungasaurus: The Cannibal King

On the isolated island of Madagascar, evolution took a dark turn with Majungasaurus crenatissimus, a predator that regularly practiced cannibalism. This medium-sized theropod, measuring about 20 feet in length, lived in an environment where food was scarce and competition was fierce. The evidence for cannibalistic behavior comes from bite marks on Majungasaurus bones that match the teeth of other Majungasaurus individuals.

The skull of Majungasaurus was built like a battering ram, with a thick, reinforced structure that could withstand tremendous impacts. This robust construction suggests these predators engaged in violent confrontations with each other, possibly fighting over territory, mates, or food sources. The single horn projecting from its skull may have been used in these intraspecific battles.

Living on an island meant that Majungasaurus faced unique evolutionary pressures. With limited prey diversity and nowhere to expand their territory, these predators turned to cannibalism as a survival strategy. This behavior, while shocking to modern sensibilities, represents a fascinating example of how predators adapt to extreme environmental constraints.

Acrocanthosaurus: The High-Spined Hunter

Prowling the forests of Early Cretaceous North America, Acrocanthosaurus atokensis stood out among predators with its distinctive sail-like ridge running along its back. This massive theropod, measuring up to 38 feet in length, combined the size of the largest predators with unique adaptations that set it apart from its contemporaries. The elongated neural spines that formed its distinctive back ridge may have supported either a sail or a muscular hump.

The arms of Acrocanthosaurus were particularly well-developed compared to other large theropods, suggesting they played an important role in hunting behavior. Unlike the reduced arms of T. rex or the vestigial limbs of Carnotaurus, Acrocanthosaurus possessed powerful forelimbs with large, curved claws that could have been used to grapple with prey or deliver devastating slashing attacks.

Trackway evidence suggests that Acrocanthosaurus was an active predator that pursued prey across considerable distances. The spacing and depth of fossilized footprints indicate these predators could maintain steady speeds while hunting, rather than relying purely on ambush tactics. This endurance hunting strategy would have been particularly effective against the large herbivores that shared their ecosystem.

Dakotaraptor: The American Giant Raptor

Just when paleontologists thought they understood Late Cretaceous predators, the discovery of Dakotaraptor steini in South Dakota’s Hell Creek Formation changed everything. This massive dromaeosaurid, measuring up to 18 feet in length, lived alongside T. rex and proved that the raptor body plan could scale up to truly gigantic proportions. With sickle claws measuring over 9 inches long, Dakotaraptor was equipped to hunt prey that would have been impossible for smaller raptors to tackle.

What makes Dakotaraptor particularly fascinating is its coexistence with Tyrannosaurus rex in the same ecosystem. Rather than competing directly, these predators likely occupied different ecological niches, with Dakotaraptor using its speed and agility to hunt medium-sized prey while T. rex focused on the largest herbivores. This niche partitioning allowed both predators to thrive in the same environment.

The discovery of flight feathers associated with Dakotaraptor suggests that even these giant raptors retained some of the ancestral features that connected them to birds. While certainly too large to fly, these feathers may have been used for display purposes or to provide insulation. The image of a giant, feathered predator stalking through Late Cretaceous forests adds another layer of wonder to these remarkable creatures.

Austroraptor: The Southern Giant

In the windswept plains of ancient Argentina, Austroraptor cabazai represented the southern hemisphere’s answer to the giant raptor body plan. This massive dromaeosaurid, measuring up to 16 feet in length, developed unique adaptations that set it apart from its northern relatives. The elongated skull and conical teeth suggest a diet that included fish and other aquatic prey, making it one of the most specialized giant raptors.

The arms of Austroraptor were proportionally smaller than those of other large dromaeosaurids, but this reduction may have been an adaptation for a more pursuit-based hunting strategy. Like modern flightless birds, Austroraptor may have relied primarily on its powerful legs for hunting, using its reduced arms primarily for balance and maneuvering during high-speed chases.

The ecosystem of Late Cretaceous Argentina was incredibly diverse, with multiple large predators competing for resources. Austroraptor’s apparent specialization for fishing and hunting smaller prey would have allowed it to avoid direct competition with giants like Giganotosaurus while still maintaining a successful predatory lifestyle. This ecological specialization demonstrates the incredible diversity of hunting strategies that evolved among Late Cretaceous predators.

Rajasaurus: The Crowned Predator

In the ancient forests of what is now India, Rajasaurus narmadensis ruled as the apex predator of its isolated ecosystem. This medium-sized theropod, measuring about 30 feet in length, possessed one of the most distinctive skull ornaments of any predator – a prominent horn projecting from the top of its head. This crown-like structure gave the dinosaur its name, which means “king lizard.”

The isolation of the Indian subcontinent during the Late Cretaceous led to the evolution of unique predator adaptations. Rajasaurus developed in an environment separated from other major landmasses, resulting in evolutionary solutions that were distinctly different from contemporary predators elsewhere. The skull horn may have been used for display purposes or in combat with other individuals.

Living on the drifting Indian plate, Rajasaurus faced prey animals that were also unique to this isolated ecosystem. The predator-prey relationships that developed in this environment were unlike those anywhere else in the world, creating a fascinating example of how geographic isolation can lead to unique evolutionary innovations. The relatively robust build of Rajasaurus suggests it was well-adapted to hunting the specific prey animals available in its environment.

Therizinosaurus: The Gentle Giant’s Claws

Not all Late Cretaceous giants were traditional predators, and Therizinosaurus cheloniformis represents one of evolution’s most surprising experiments. This massive theropod, measuring up to 16 feet tall, possessed claws that could reach over 3 feet in length, yet it was entirely herbivorous. The enormous claws that initially suggested a fearsome predator were actually adaptations for stripping vegetation from tall trees.

The discovery that Therizinosaurus was herbivorous revolutionized our understanding of theropod evolution. Here was a lineage of predators that had completely abandoned carnivory, developing into massive plant-eaters that could compete with sauropods for high-growing vegetation. The massive claws served as sophisticated harvesting tools, allowing these giants to access food sources unavailable to other herbivores.

The ecological impact of Therizinosaurus would have been enormous. As one of the largest herbivores of its time, it would have shaped plant communities through its feeding behavior while also serving as prey for the largest predators. The coexistence of gentle giants like Therizinosaurus with apex predators like Tarbosaurus created complex ecological relationships that we’re still working to understand.

The Predator’s Paradise Lost

The Late Cretaceous period ended with one of the most dramatic extinction events in Earth’s history, bringing an end to the age of giant predators. The asteroid impact that occurred 66 million years ago didn’t just eliminate the dinosaurs – it ended an entire ecosystem built around some of the most sophisticated predators ever to walk the Earth. The diversity of hunting strategies, body plans, and ecological adaptations that had evolved over millions of years was wiped out in a geological instant.

What survived the extinction event were the small, adaptable species that could exploit new ecological niches in the post-impact world. The age of giant predators was over, replaced by a world where mammals would eventually develop their own sophisticated hunting strategies. Yet the legacy of these Late Cretaceous giants lives on in their descendants – the birds that still employ many of the same hunting techniques developed by their dinosaurian ancestors.

The study of Late Cretaceous predators continues to reveal new insights into predator evolution and behavior. Each discovery adds another piece to the puzzle of how these magnificent creatures lived, hunted, and interacted with their environment. The more we learn about these ancient predators, the more we realize that the Late Cretaceous was not just the age of T. rex, but the age of predatory innovation on a scale that the world has never seen since.

The Late Cretaceous period stands as a testament to the incredible diversity of predatory strategies that evolution can produce. From the pack-hunting Mapusaurus to the semi-aquatic Spinosaurus, from the high-speed Carnotaurus to the gentle giant Therizinosaurus, this era showcased predatory adaptations that spanned every conceivable ecological niche. These weren’t just larger versions of modern predators – they were entirely unique solutions to the challenges of survival in a world unlike anything that exists today. The next time you see a T. rex skeleton in a museum, remember that it represents just one member of an incredibly diverse cast of characters that made the Late Cretaceous one of the most fascinating chapters in the history of life on Earth. What other secrets about these magnificent predators are still waiting to be discovered in the rocks beneath our feet?