Deep within the fossilized remains of mighty dinosaurs, paleontologists have discovered something truly remarkable—smooth, polished stones that once served as nature’s own food processors. These aren’t just random rocks that happened to end up in the wrong place. They’re gastroliths, and they tell an incredible story about how some of the most massive creatures ever to walk the Earth managed to digest their meals.

The Mystery of the Smooth Stones

Imagine digging through a dinosaur skeleton and finding a collection of perfectly polished stones nestled where the stomach should be. That’s exactly what happened to early paleontologists, and it left them scratching their heads for decades. These stones, called gastroliths, are far too smooth and uniform to be accidental—they show clear signs of having been tumbled and worn down by constant friction.

The word “gastrolith” comes from Greek, meaning “stomach stone,” which perfectly describes their function. Unlike the jagged rocks you’d find scattered around a dig site, these stones have a distinctive appearance that immediately sets them apart. They’re typically made of hard materials like quartzite, granite, or chert, and their surfaces gleam with a polish that could only come from years of grinding against other stones.

How Dinosaurs Became Living Rock Tumblers

The process of how these stones became so perfectly polished is fascinating in itself. When dinosaurs swallowed these rocks, they didn’t just sit there doing nothing—they became part of an incredibly efficient digestive system. The muscular walls of the dinosaur’s gizzard would contract rhythmically, causing the stones to tumble and grind against each other and against tough plant material.

This constant churning action served two purposes: it broke down fibrous plant matter that would otherwise be impossible to digest, and it gradually polished the stones to a mirror-like finish. The harder the rock, the better it worked as a grinding tool, which explains why dinosaurs seemed to have a preference for particularly tough stone types.

Giants That Needed Help Chewing

The dinosaurs that used gastroliths weren’t your typical sharp-toothed predators. These were massive herbivores like sauropods—the long-necked giants that could reach lengths of over 100 feet. Think about it: these creatures had relatively small heads compared to their enormous bodies, and their teeth weren’t designed for extensive chewing like modern mammals.

Sauropods like Brontosaurus and Diplodocus had to swallow their food quickly and efficiently, often gulping down entire branches and leaves without much processing. Without the ability to chew their food properly, they needed another way to break down all that tough plant material. Enter the gastrolith—nature’s solution to a prehistoric digestive dilemma.

The Science Behind Stone Digestion

The mechanics of gastrolith digestion are surprisingly sophisticated. The stones worked in a specialized part of the digestive system called the gizzard, which functioned much like a powerful mill. This muscular chamber could exert tremendous pressure, crushing and grinding plant material with the help of the swallowed rocks.

Research suggests that the grinding action of gastroliths could increase the surface area of plant material by up to 30 times, making it much easier for digestive enzymes to break down cellulose and extract nutrients. This process was so effective that it allowed these massive dinosaurs to extract maximum nutrition from relatively low-quality plant matter.

Birds: The Living Proof

You don’t have to look far to see gastroliths in action today—many modern birds use the exact same system. Chickens, ducks, and geese regularly swallow small stones and gravel to help digest their food. Bird enthusiasts often notice their feathered friends pecking at gravel or sand, and now you know why.

The similarity between dinosaur and bird digestion isn’t coincidental—birds are, after all, direct descendants of dinosaurs. Watching a chicken’s gizzard work is like getting a window into how massive sauropods processed their meals millions of years ago. It’s a living demonstration of an ancient survival strategy that has stood the test of time.

Fossil Evidence That Tells a Story

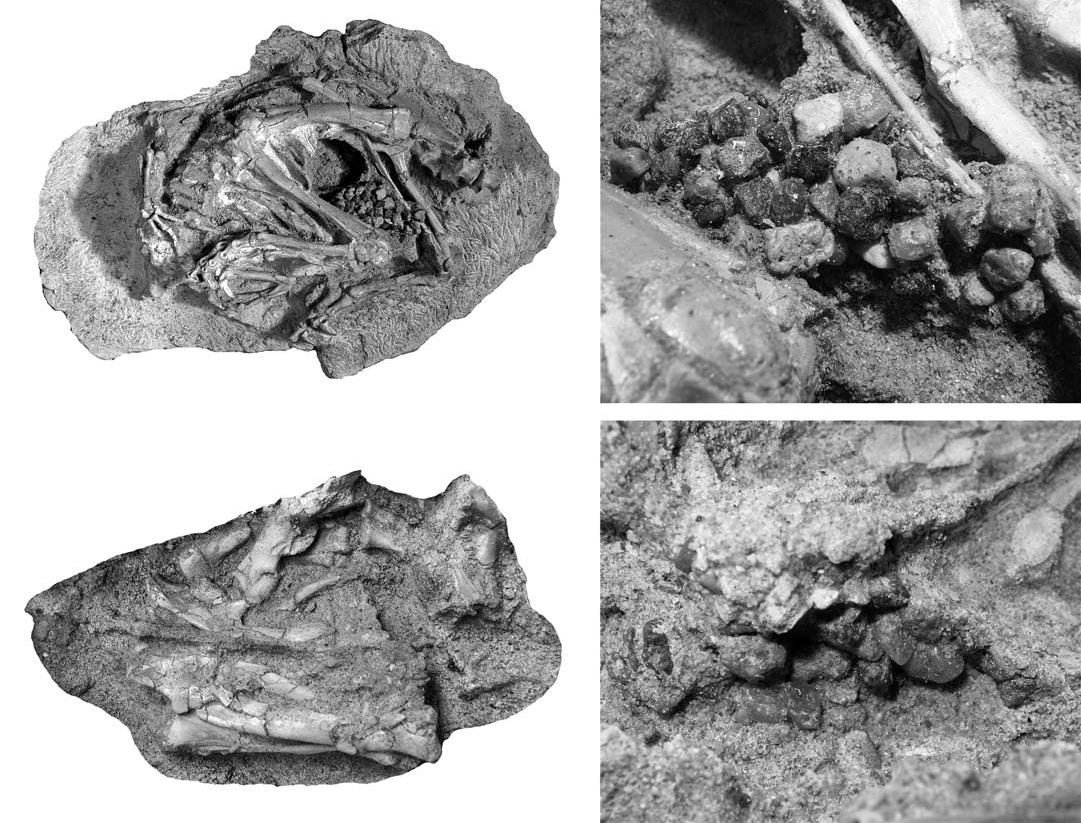

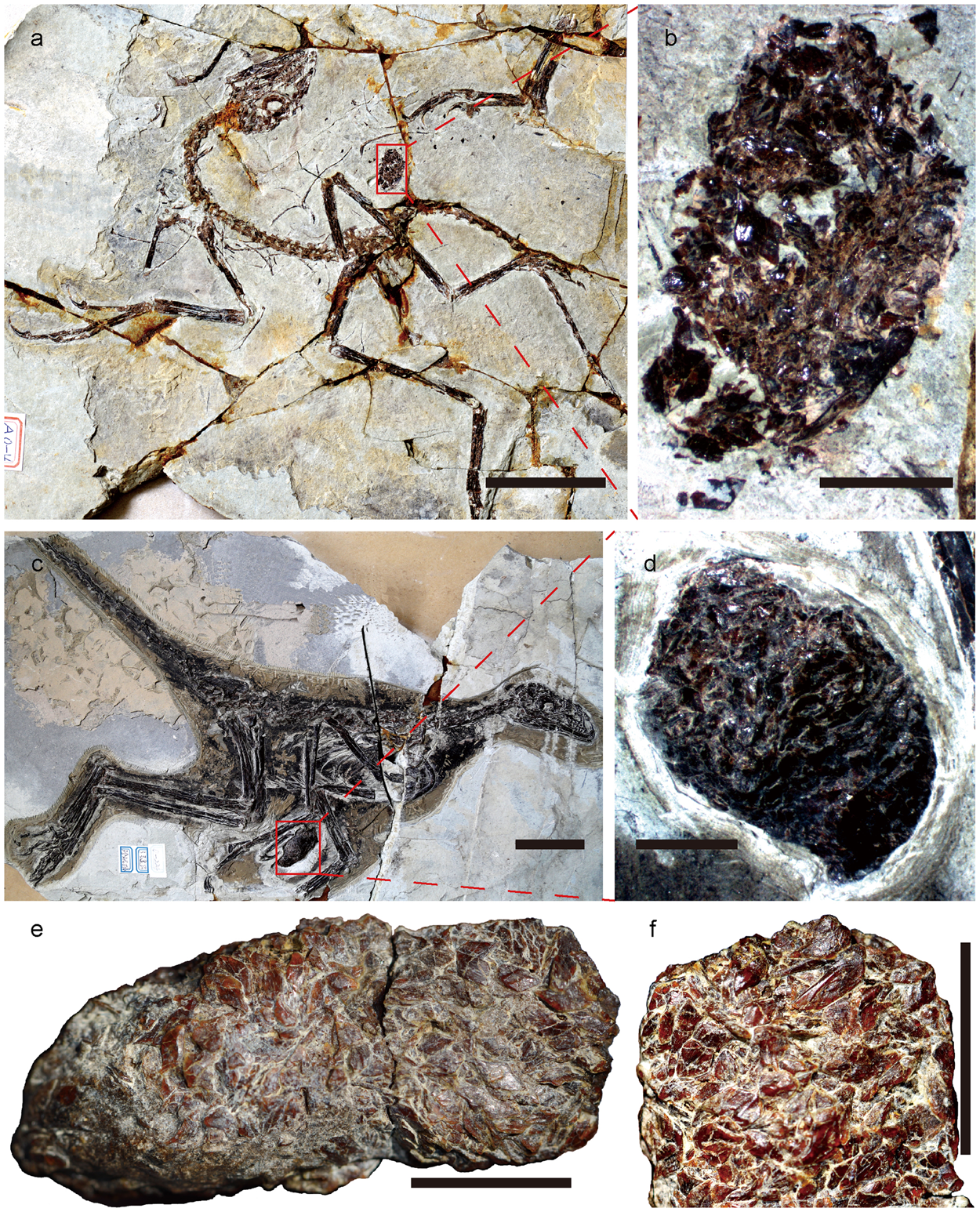

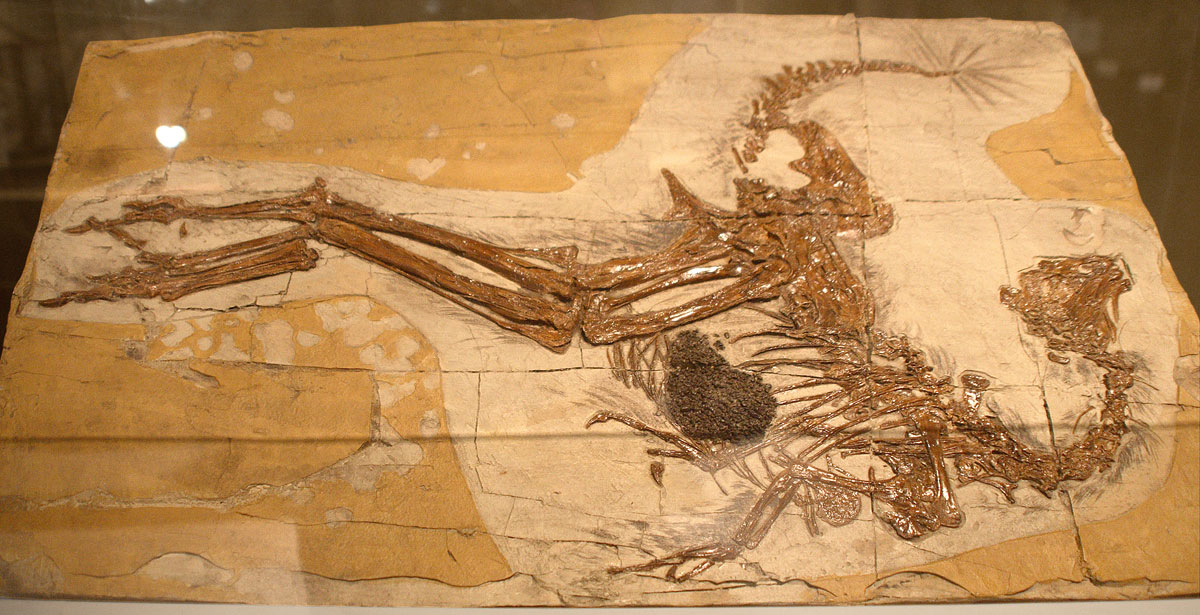

The fossil record provides compelling evidence for gastrolith use among dinosaurs. Paleontologists have found collections of smooth stones in association with dinosaur skeletons at sites around the world, from North America to China. These discoveries aren’t random—the stones are typically found in clusters where the dinosaur’s stomach would have been located.

Some of the most convincing evidence comes from articulated skeletons where the bones are still in their original positions. In these cases, the gastroliths are found exactly where you’d expect them to be if they were indeed stomach stones. The positioning is so consistent that it’s become one of the key ways paleontologists identify potential gastrolith sites.

Size Matters in the Stone Selection

Not all stones made good gastroliths—dinosaurs were surprisingly selective about their rock choices. The size of the stones correlates directly with the size of the dinosaur, suggesting that these animals had an instinctive understanding of what would work best for their digestive needs. Smaller dinosaurs used pebbles, while the largest sauropods swallowed stones the size of baseballs or even larger.

The optimal size seems to have been about 1-2% of the animal’s body weight in total stone mass. This ratio provided the perfect balance between grinding efficiency and the energy cost of carrying around a belly full of rocks. Too small, and the stones wouldn’t provide enough grinding action; too large, and they’d be metabolically expensive to carry around.

The Great Gastrolith Debate

Despite the compelling evidence, the gastrolith theory isn’t without its skeptics. Some paleontologists argue that not all smooth stones found with dinosaur fossils are necessarily gastroliths. They point out that stones can become polished through other geological processes, and that some supposed gastroliths might have been deposited by streams or other natural forces after the dinosaur died.

This debate has led to more rigorous criteria for identifying true gastroliths. Scientists now look for specific characteristics: the stones must be found in anatomically correct positions, they must be made of materials not locally available, and they must show the distinctive polish patterns that come from biological grinding rather than water action.

Crocodiles and Other Modern Stone Swallowers

Dinosaurs weren’t the only ancient creatures to use gastroliths, and they’re not the only modern animals to employ this strategy either. Crocodiles and alligators regularly swallow stones, though the purpose isn’t entirely clear. Some researchers believe the stones help with digestion, while others think they might serve as ballast to help these semi-aquatic predators control their buoyancy.

Seals and sea lions also swallow stones, and in their case, the ballast theory makes more sense. These marine mammals need to control their position in the water column while diving, and stones in their stomachs could help them maintain neutral buoyancy at different depths.

The Chemistry of Digestion

The chemical environment inside a dinosaur’s gizzard was far from gentle. The combination of powerful acids, digestive enzymes, and mechanical grinding created conditions that could break down even the toughest plant materials. The gastroliths had to survive in this harsh environment while maintaining their effectiveness as grinding tools.

Over time, the constant acid exposure and mechanical wear would have gradually broken down the stones themselves. This means that dinosaurs probably had to replace their gastroliths periodically, swallowing new stones as the old ones became too small or too worn to be effective. It’s a fascinating example of how these ancient animals had to actively maintain their digestive “equipment.”

Geographic Clues in Stone Selection

One of the most intriguing aspects of gastrolith research is the discovery that many dinosaurs traveled considerable distances to find suitable stones. Analysis of gastrolith composition often reveals rock types that don’t occur naturally in the area where the dinosaur fossil was found. This suggests that these animals made deliberate journeys to specific locations where they could find the right kind of stones.

These “gastrolith pilgrimages” provide valuable insights into dinosaur behavior and migration patterns. Some paleontologists believe that knowledge of good stone sources might have been passed down through generations, creating traditional routes that dinosaur herds would follow to maintain their digestive health.

Implications for Dinosaur Metabolism

The presence of gastroliths has significant implications for our understanding of dinosaur metabolism and lifestyle. The fact that these massive animals invested energy in finding, swallowing, and carrying around stones suggests that they had very active digestive systems and high metabolic rates. This challenges older ideas about dinosaurs being slow, cold-blooded creatures.

The efficiency of gastrolith digestion may have been one of the key factors that allowed sauropods to grow to such enormous sizes. By maximizing the nutrition they could extract from plant matter, these dinosaurs could support their massive bodies on what might otherwise have been inadequate food resources.

Preservation and Study Challenges

Studying gastroliths presents unique challenges for paleontologists. Unlike bones, which can be definitively identified as belonging to a particular species, stones are much harder to connect to specific dinosaurs. The geological processes that preserve fossils can also scatter or destroy gastrolith assemblages, making it difficult to determine their original arrangement.

Modern imaging techniques like CT scanning have revolutionized gastrolith research, allowing scientists to see inside fossil specimens without damaging them. These non-invasive methods have revealed gastrolith clusters that were previously hidden within rock matrices, providing new insights into dinosaur digestive anatomy.

The Future of Gastrolith Research

As technology advances, our understanding of gastroliths continues to evolve. New analytical techniques are helping scientists determine not just what stones dinosaurs swallowed, but where those stones came from and how they were used. Isotope analysis can reveal the geographic origin of stones, while microscopic examination of wear patterns provides clues about digestive processes.

These gastroliths represent more than just ancient rocks—they’re windows into the daily lives of creatures that lived millions of years ago. Each polished stone tells a story of survival, adaptation, and the remarkable ways life finds solutions to fundamental challenges. The next time you see a bird pecking at gravel or watch a chicken scratch in the dirt, remember that you’re witnessing an ancient strategy that once helped the largest land animals in Earth’s history thrive in their prehistoric world. What other secrets might these simple stones still hold?