Picture this: You’re standing in a Kansas wheat field, golden stalks swaying in the breeze, when you stumble upon a massive skull with razor-sharp teeth longer than your fingers. This isn’t science fiction – it’s the incredible reality of what lies beneath America’s heartland. Millions of years ago, where farmers now harvest corn and cattle graze peacefully, colossal marine predators ruled an ancient ocean that stretched from the Gulf of Mexico to the Arctic Circle.

The Western Interior Seaway transformed North America into something unrecognizable – a continent split in half by a shallow, tropical sea teeming with creatures that would make today’s great white sharks look like goldfish. These weren’t just big fish; they were evolutionary masterpieces, perfectly adapted killing machines that dominated their watery world for over 40 million years.

The Great Drowning of North America

Around 100 million years ago, during the Late Cretaceous Period, our planet was a dramatically different place. Sea levels rose to extraordinary heights, flooding vast portions of continents worldwide. In North America, this massive flooding event created what scientists call the Western Interior Seaway – a body of water that would make the Mediterranean Sea seem like a pond.

This ancient ocean wasn’t just large; it was transformative. The seaway stretched over 2,500 miles from north to south and reached widths of up to 600 miles. Imagine driving from New York to Los Angeles and spending half that journey crossing open ocean – that’s the scale we’re talking about.

The flooding happened gradually, but its effects were profound. As polar ice caps melted and tectonic activity shifted the ocean floor, water levels rose by as much as 800 feet above today’s levels. This created perfect conditions for marine life to flourish in ways we can barely comprehend today.

Kansas: The Unexpected Ocean Floor

Today’s Kansas might be famous for tornadoes and wheat, but 80 million years ago, it sat at the bottom of a warm, shallow sea. The Smoky Hill Chalk formation, now exposed across western Kansas, tells an incredible story written in limestone and fossilized remains. This chalky white rock formation extends for hundreds of miles and represents millions of years of accumulated marine life.

What makes Kansas particularly special for paleontologists is the exceptional preservation conditions that existed in this ancient sea. The warm, oxygen-poor waters at the bottom of the seaway created perfect conditions for fossilization. When marine creatures died, they sank into the soft sediment and were quickly buried, preventing decay and preserving even delicate structures.

The chalk itself is largely composed of microscopic marine organisms called coccoliths – tiny calcium carbonate plates from single-celled algae. These organisms were so abundant that their accumulated remains formed massive limestone deposits that we can still see today.

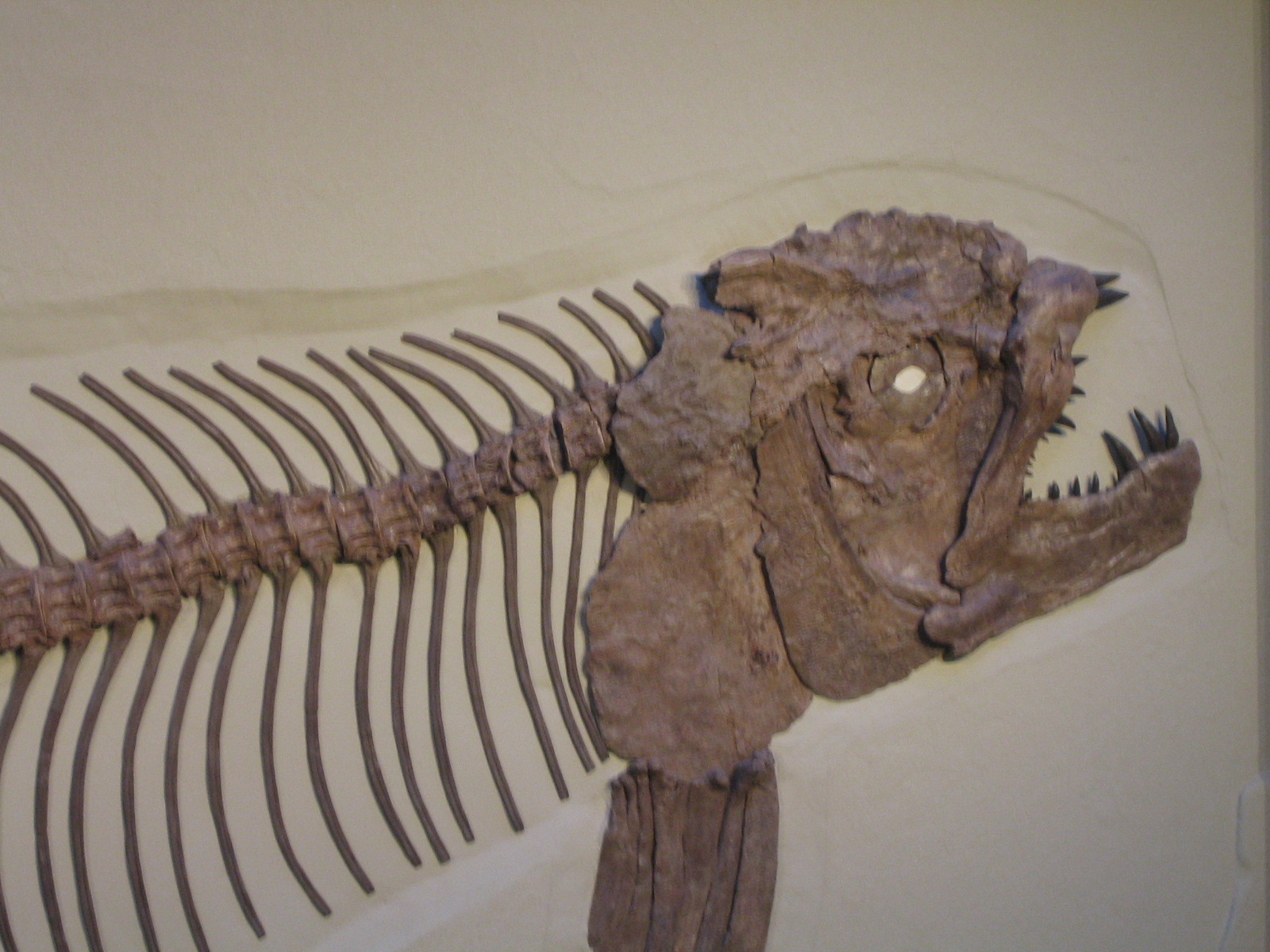

Tylosaurus: The Underwater Tyrant

Among the most fearsome predators ever to prowl Kansas waters was Tylosaurus, a mosasaur that could grow up to 50 feet long. Picture a massive snake with flippers instead of legs, armed with a mouth full of sharp, backward-curving teeth, and you’re getting close to understanding this prehistoric terror. These weren’t dinosaurs, but rather marine reptiles related to modern snakes and lizards that had adapted completely to ocean life.

Tylosaurus possessed a distinctive ramming snout – a solid, club-like extension of its skull that it likely used to stun prey or engage in battles with rivals. Fossil evidence shows bite marks and healed wounds on Tylosaurus specimens, suggesting these giants weren’t above cannibalism when the opportunity arose.

Their hunting strategy was probably similar to modern orcas, using their powerful tails to propel themselves through the water at incredible speeds. When they struck, their victims had little chance of escape from those crushing jaws.

Xiphactinus: The Bulldog Fish from Hell

If Tylosaurus was the underwater serpent, then Xiphactinus was the sea’s ultimate predator fish. Growing up to 20 feet long, this bony fish earned the nickname “bulldog fish” for its massive head and powerful jaws lined with fang-like teeth. What sets Xiphactinus apart in the fossil record is the incredible preservation of specimens that died with their last meals still inside them.

The most famous Xiphactinus fossil, nicknamed “Fish-within-a-Fish,” shows a 14-foot specimen that died after swallowing a 6-foot fish called Gillicus. The smaller fish apparently struggled so violently inside the predator’s stomach that it ruptured internal organs, killing both predator and prey. This remarkable fossil is now displayed at the Sternberg Museum in Kansas, offering visitors a glimpse into an ancient life-and-death struggle.

Xiphactinus likely ambushed its prey from below, using its streamlined body to rocket upward and engulf smaller fish in its cavernous mouth. Its success as a predator is evident from the numerous fossils found throughout the Western Interior Seaway.

Cretoxyrhina: The Ginsu Shark

Long before great whites ruled the oceans, Cretoxyrhina mantelli terrorized the Western Interior Seaway. This prehistoric shark, nicknamed the “Ginsu shark” for its incredibly sharp teeth, could reach lengths of 24 feet and possessed some of the most efficient cutting teeth ever evolved. Unlike modern sharks that primarily rely on crushing and tearing, Cretoxyrhina’s teeth were designed for precision slicing.

The shark’s teeth were so sharp and numerous that they could slice through bone with ease. Paleontologists have found mosasaur vertebrae with perfectly clean cuts that could only have been made by Cretoxyrhina’s razor-like dental arsenal. These cuts are so precise they look like they were made with modern surgical instruments.

What made Cretoxyrhina particularly dangerous was its intelligence and hunting strategy. Evidence suggests these sharks hunted in coordinated groups, much like modern wolves, allowing them to take down prey much larger than themselves, including juvenile mosasaurs and large fish.

Platecarpus: The Agile Hunter

While Tylosaurus dominated through size and brute force, Platecarpus succeeded through speed and agility. This smaller mosasaur, typically reaching 14 feet in length, was built like an underwater cheetah. Its streamlined body, powerful tail, and relatively lightweight build made it perfectly suited for pursuing fast-moving prey through the ancient seas.

Platecarpus had proportionally larger eyes than its giant cousins, suggesting it relied heavily on vision for hunting. This adaptation would have been particularly useful in the murky waters of the Western Interior Seaway, where visibility was often limited. The shark’s flexible spine and powerful swimming muscles allowed it to make sharp turns and sudden direction changes that larger predators couldn’t match.

Fossil evidence shows that Platecarpus primarily fed on smaller fish, squid-like creatures, and even birds that ventured too close to the water’s surface. Its teeth were perfectly adapted for grasping slippery prey, with a slight curve that prevented escape once the victim was caught.

Hesperornis: The Toothed Terror Bird

Not all the monsters of the Western Interior Seaway lived entirely underwater. Hesperornis, a flightless diving bird about six feet long, ruled the interface between sea and sky. What made this bird truly terrifying was its mouth full of sharp, backward-pointing teeth – a feature that no modern bird possesses.

These prehistoric birds were perfectly adapted for underwater hunting, with powerful legs positioned far back on their bodies for maximum swimming efficiency. Their wings had evolved into small, useless appendages, but their torpedo-shaped bodies could slice through water with remarkable speed. When hunting, Hesperornis would dive deep beneath the surface, using its toothed beak to snatch fish and small marine reptiles.

The presence of teeth in Hesperornis represents an evolutionary experiment that modern birds have abandoned. These teeth were not separate structures like mammalian teeth, but rather extensions of the jaw bone itself, making them incredibly strong and well-suited for gripping slippery prey.

Gillicus: The Silvery Survivor

While giants dominated the headlines, smaller fish like Gillicus formed the foundation of the Western Interior Seaway’s food web. These herring-like fish, typically 2-6 feet long, traveled in massive schools that could stretch for miles. Their abundance supported the entire ecosystem, providing food for everything from small sharks to giant mosasaurs.

Gillicus possessed large eyes and a streamlined body perfectly adapted for detecting predators and making quick escapes. Their schooling behavior offered protection through numbers – while a few individuals might fall victim to predators, the majority of the school would survive. This survival strategy was so successful that Gillicus fossils are among the most common found in Kansas today.

The preservation of Gillicus schools in the fossil record provides scientists with incredible insights into ancient marine ecosystems. Some fossil slabs contain dozens of complete Gillicus specimens, apparently killed simultaneously by rapid burial or oxygen depletion events.

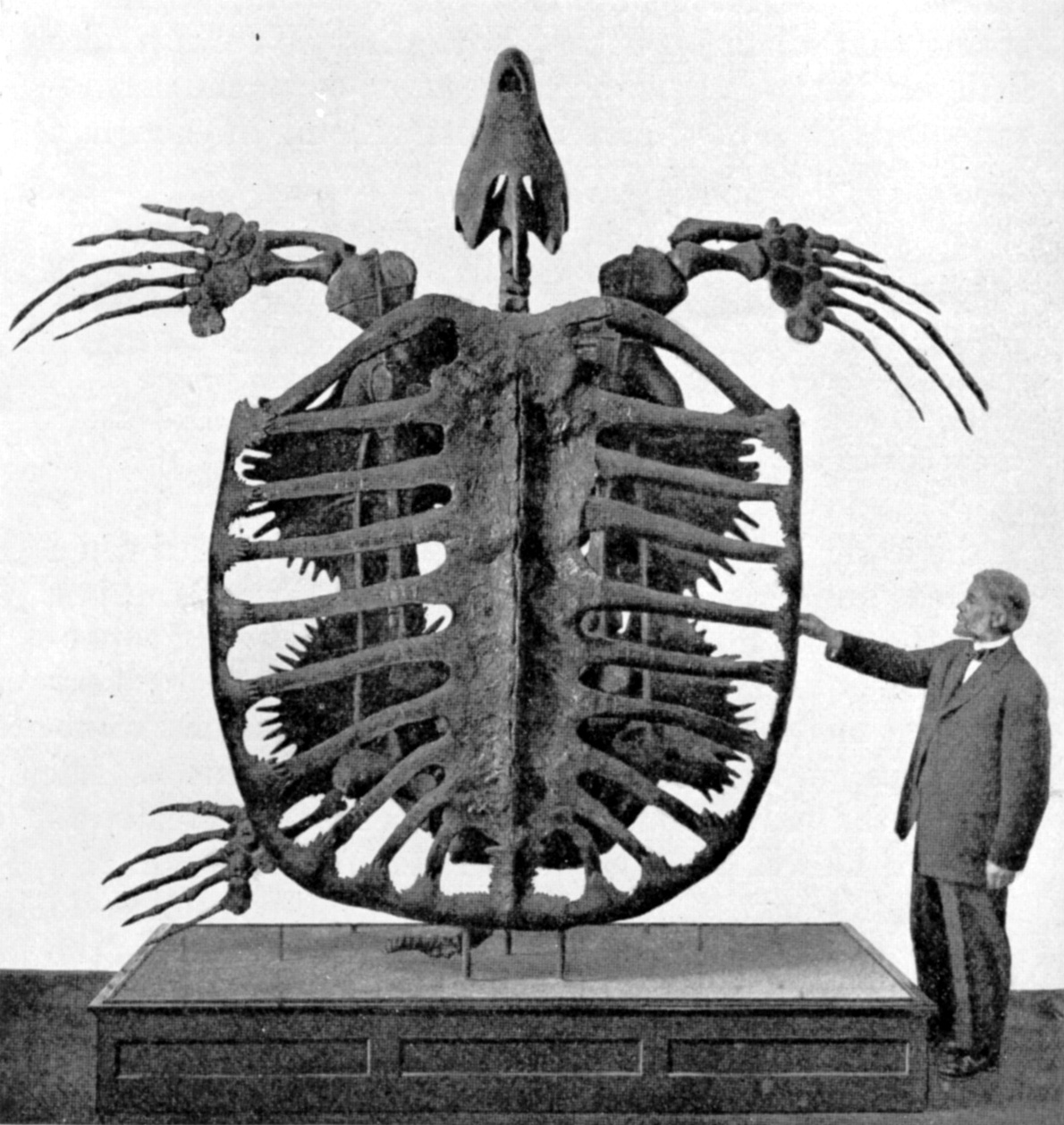

Archelon: The Gentle Giant

Not every creature in the Western Interior Seaway was a fearsome predator. Archelon, the largest sea turtle that ever lived, cruised these ancient waters as a gentle giant reaching lengths of 12 feet and weighing over 4,400 pounds. Unlike modern sea turtles with their hard shells, Archelon had a leathery carapace similar to today’s leatherback turtles, but on a massive scale.

These ancient turtles were perfectly adapted for life in the open ocean, with powerful flippers that could propel their massive bodies through the water with surprising grace. Their diet consisted primarily of jellyfish, squid, and other soft-bodied creatures, which they captured using their sharp, beak-like mouths.

Archelon represents the peaceful side of the Western Interior Seaway, showing that not every large marine reptile was a predator. Their presence indicates that the ancient seas were rich enough in plankton and small organisms to support massive filter-feeding and soft-prey specialists.

Squalicorax: The Opportunistic Scavenger

While the giants grabbed most of the attention, smaller sharks like Squalicorax played crucial roles as both predators and scavengers in the Western Interior Seaway. These 6-foot sharks were the ocean’s cleanup crew, feeding on everything from fish to marine reptile carcasses. Their triangular, serrated teeth were perfect for both catching live prey and stripping meat from bones.

Squalicorax teeth are among the most common shark fossils found in Kansas, suggesting these sharks were incredibly abundant. Their success came from their adaptability – they could hunt when opportunities arose, but were equally happy to feed on dead or dying creatures. This flexibility allowed them to thrive in an ecosystem dominated by much larger predators.

The abundance of Squalicorax fossils also tells us something important about the ancient ocean’s productivity. These sharks required a constant food supply to maintain their populations, indicating that the Western Interior Seaway was incredibly rich in marine life at all levels of the food chain.

Pteranodon: Masters of the Ancient Skies

While sea monsters ruled the waters below, equally impressive creatures commanded the skies above the Western Interior Seaway. Pteranodon, with wingspans reaching 23 feet, soared over the ancient ocean like living airplanes. These pterosaurs weren’t dinosaurs, but rather flying reptiles that had evolved sophisticated adaptations for aerial life.

Pteranodon possessed hollow bones and air sacs throughout their bodies, making them incredibly lightweight despite their massive size. Their long, toothless beaks were perfectly designed for snatching fish from the water’s surface, much like modern pelicans. The distinctive crest extending from the back of their skull may have served as a rudder during flight or played a role in species recognition.

These aerial giants likely spent most of their time soaring over the seaway, using thermal currents to stay aloft with minimal energy expenditure. When feeding opportunities arose, they could dive down to snatch fish or squid from the surface, then return to their aerial domain.

Dolichorhynchops: The Long-Necked Marvel

Among the most elegant creatures in the Western Interior Seaway was Dolichorhynchops, a plesiosaur with an extraordinarily long neck that could comprise nearly half of its total body length. These 17-foot marine reptiles moved through the water like underwater giraffes, using their extended necks to probe crevices and pursue prey in areas their bulky bodies couldn’t reach.

The long neck wasn’t just for show – it was a highly sophisticated hunting tool. Dolichorhynchops could keep its body motionless while extending its neck to ambush unsuspecting fish and squid. The element of surprise was crucial, as the neck could strike with lightning speed to capture prey before it could escape.

Recent studies of Dolichorhynchops fossils have revealed sophisticated adaptations in their neck vertebrae, including specialized joints that allowed for incredible flexibility. This anatomical precision shows how evolution fine-tuned these creatures for their specific ecological niche.

The Great Extinction: When the Seas Retreated

The golden age of sea monsters came to an abrupt end around 66 million years ago, coinciding with the mass extinction event that eliminated non-avian dinosaurs. As sea levels dropped and the Western Interior Seaway drained away, the marine giants that had ruled these waters for millions of years found themselves without a home. The inland seas that had supported such incredible diversity became dry land, forcing marine life back to the world’s oceans.

The retreat wasn’t gradual – geological evidence suggests it happened relatively quickly in geological terms, over perhaps a few hundred thousand years. For creatures adapted to shallow, warm seas, this represented a catastrophic loss of habitat. The specialized ecosystems that had evolved in the Western Interior Seaway couldn’t simply migrate to the deeper, cooler waters of the open ocean.

Climate change, volcanic activity, and the famous asteroid impact all played roles in this transformation. The combination of factors created a perfect storm that ended one of the most remarkable chapters in Earth’s marine history, leaving behind only fossils to tell their incredible story.

Modern Discoveries: Kansas Continues to Amaze

The story of Kansas’s fossil sea monsters is far from over. Every year, paleontologists and amateur fossil hunters continue to make remarkable discoveries that reshape our understanding of these ancient ecosystems. Recent finds have included new species of mosasaurs, exceptionally preserved fish specimens, and even fossilized soft tissues that provide unprecedented insights into how these creatures lived.

Modern technology is revolutionizing how scientists study these ancient remains. CT scanning allows researchers to examine internal structures without damaging precious fossils, while advanced chemical analysis can reveal information about diet, metabolism, and even body temperature. These tools are helping paint an increasingly detailed picture of life in the Western Interior Seaway.

The Sternberg Museum of Natural History in Hays, Kansas, continues to be a world-renowned center for marine fossil research, housing one of the most important collections of Western Interior Seaway specimens in the world. Visitors can see the actual fossils that have helped scientists understand these remarkable creatures.

The Western Interior Seaway represents one of the most extraordinary periods in North America’s natural history, when inland seas supported ecosystems unlike anything we see today. These ancient waters were home to some of the largest, most specialized marine predators ever to exist, creatures so perfectly adapted to their environment that they dominated their world for tens of millions of years. The fossils they left behind in Kansas and across the American heartland continue to amaze scientists and visitors alike, offering tangible connections to a time when sea monsters truly ruled the Earth. What other secrets might still lie buried beneath America’s farmland, waiting for the next curious explorer to uncover them?