Think you know everything about prehistoric life? Picture this: while great white cruised ancient oceans at roughly 2-3 miles per hour, some dinosaurs were already mastering aquatic movements that would make modern marine predators jealous. These weren’t your typical land-bound giants stumbling into water. These were precision-engineered swimming machines with adaptations that took millions of years to perfect.

The idea might sound impossible at first. After all, most of us grew up imagining dinosaurs as strictly terrestrial creatures, stomping through forests and plains. Yet recent discoveries have shattered that misconception completely. Scientists now know that several dinosaur species developed remarkable aquatic abilities, complete with dense bones for buoyancy control, paddle-like tails for propulsion, and specialized feeding techniques that rivaled the most skilled marine hunters.

So let’s dive in and discover which prehistoric giants could have left today’s eating their bubbles.

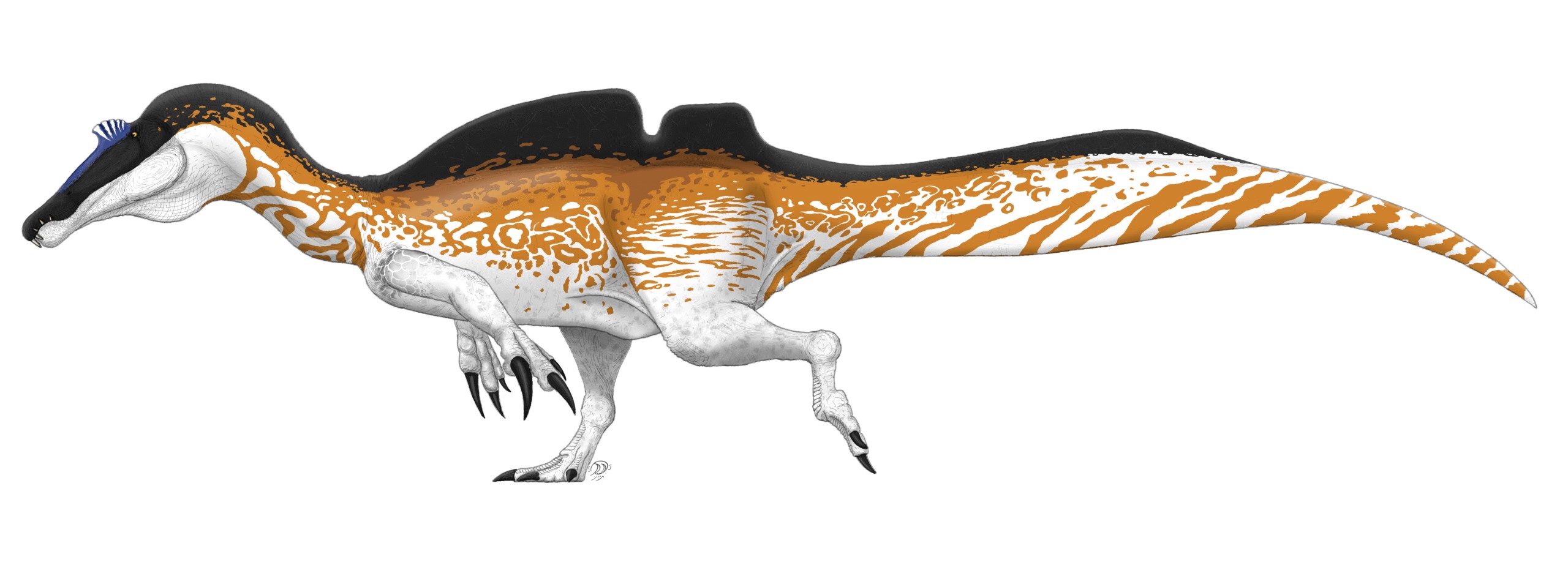

Spinosaurus: The Paddle-Tailed Speed Demon

The mighty Spinosaurus stretched an incredible 50-59 feet in length and holds the distinction of being the first dinosaur confirmed to have swimming abilities. This wasn’t just any dinosaur taking a casual dip. Scientists discovered that Spinosaurus possessed dense bones specifically designed to help maintain neutral buoyancy in freshwater environments, along with a distinctive paddle-like tail optimized for aquatic propulsion.

What made this giant so effective in water? Its snout contained specialized pressure receptors that allowed it to detect swimming prey without even seeing them, essentially giving it a sixth sense for underwater hunting. While its jaws weren’t built for crushing like a crocodile’s, they were perfectly adapted for quickly snapping at fast-moving fish, giving it a significant advantage over lumbering that relied purely on brute force.

Baryonyx: The Heavy-Clawed Fishing Expert

Recent studies revealed that Baryonyx from prehistoric England possessed relatively dense bones suitable for deep-water swimming, making it another skilled aquatic hunter alongside its famous cousin Spinosaurus. Despite being a land-dwelling creature, this “heavy claw” dinosaur could grab fish directly from rivers and swim effectively in shallow waters using its distinctive serrated teeth.

The secret weapon? Its name literally translates to “Heavy Claw,” referring to the massive claw on its first finger. Picture a creature that combined the fishing skills of a modern bear with the swimming efficiency of a seal. Bone density analysis confirmed that Baryonyx had the physical adaptations necessary for underwater submersion and hunting, capabilities that would have made it formidable against any ancient shark species.

Suchomimus: The Crocodile Mimic Swimmer

Suchomimus from Niger presents an interesting case – while it had bones more similar to land-dwelling predators like T. rex, it still possessed the characteristic crocodile-like features of its spinosaurid family. Though its bone density suggests it wasn’t a deep-water swimmer like its relatives, this “crocodile mimic” still lived by water and specialized in catching fish.

What set Suchomimus apart was its approach to aquatic hunting. Rather than diving deep like Spinosaurus or Baryonyx, this clever predator likely employed ambush tactics from shorelines and shallow waters. With conical teeth resembling those of crocodiles and an elongated snout perfectly designed for aquatic prey capture, it could outmaneuver in the crucial transition zones between water and land where many marine predators struggled to operate effectively.

Irritator: The Brazilian Water Hunter

Irritator from Brazil belongs to the same spinosaurid family that produced the most accomplished aquatic dinosaurs. Scientific analysis indicates that South American spinosaurids like Irritator were intermediate between different spinosaur groups, suggesting unique adaptations. This positioning in the evolutionary tree hints at specialized swimming capabilities that may have been distinct from its African and European relatives.

The Brazilian environment during the Cretaceous period was rich with river systems and coastal areas, providing the perfect training ground for aquatic adaptations. Evidence suggests spinosaurs were opportunistic predators that could hunt both fish and terrestrial prey, giving Irritator a versatility that would have been invaluable when competing with marine predators. Its ability to seamlessly transition between aquatic and terrestrial hunting would have provided significant advantages over limited to water-only environments.

Siamosaurus: The Asian Aquatic Specialist

Siamosaurus represents the spinosaurine branch of the family tree and has been confirmed as a member of the specialized Spinosaurinae subfamily. Like other spinosaurines, it possessed unserrated straight teeth that were widely spaced – a design perfectly suited for gripping slippery aquatic prey. This dental arrangement was fundamentally different from typical land predators and clearly indicates aquatic specialization.

The Asian waterways where Siamosaurus lived were teeming with fish and other aquatic life, creating an environment where swimming efficiency would have been crucial for survival. Research indicates that these spinosaurs developed swimming modes involving oscillating flukes, different from the eel-like undulation previously suggested. This advanced propulsion system would have given Siamosaurus speed advantages over contemporary that relied on simpler tail movements.

Ichthyovenator: The Fish Hunter of Laos

Ichthyovenator from Laos has been classified within the Spinosaurinae subfamily, indicating close relationships with the most aquatically-adapted dinosaurs. Its name literally means “fish hunter,” leaving little doubt about its preferred prey and habitat. Scientific analysis of spinosaur locomotion suggests these dinosaurs were highly specialized for aquatic movement from early in their evolutionary development.

The Southeast Asian environment provided unique challenges and opportunities for aquatic dinosaurs. Ichthyovenator and its relatives developed morphology unlike any other known aquatic tetrapod, suggesting innovative solutions to underwater hunting that modern never evolved. This specialized anatomy likely gave it superior maneuverability and hunting efficiency compared to operating in the same ancient waters.

Oxalaia: The South American River Master

Oxalaia represents another member of the advanced Spinosaurinae subfamily, though it may be synonymous with Spinosaurus itself. Studies of South American spinosaurids reveal they were intermediate between major spinosaur groups, suggesting unique evolutionary adaptations. This intermediate position indicates Oxalaia developed distinct swimming capabilities adapted to South American river systems.

The rivers of prehistoric South America were vastly different from modern waterways, filled with giant fish and other aquatic prey that required specialized hunting techniques. Like other spinosaurs, Oxalaia was likely an opportunistic predator capable of taking both aquatic and terrestrial prey. This flexibility would have been crucial when competing with ancient and other marine predators for limited resources in shared habitats.

Angaturama: The Mysterious Brazilian Swimmer

Angaturama from Brazil may be synonymous with Irritator but represents the intermediate evolutionary position of South American spinosaurids. Research indicates these Brazilian forms possessed craniodental features that placed them between the major spinosaur groups. This unique positioning suggests Angaturama developed swimming adaptations that were distinct from both African and European relatives.

The mystery surrounding Angaturama’s exact classification highlights how diverse spinosaur swimming adaptations became across different continents. Scientists are still uncovering the full ecological breadth of non-avian dinosaurs, with spinosaurs becoming more puzzling the more we learn about them. What’s clear is that Angaturama possessed the fundamental spinosaur body plan optimized for aquatic hunting, giving it advantages over in prehistoric Brazilian waters.

Sigilmassasaurus: The Moroccan Water Predator

Sigilmassasaurus from Morocco may be synonymous with the famous Spinosaurus, but whether separate or not, it represents the pinnacle of spinosaur aquatic adaptation. The Moroccan fossil record provides crucial evidence of dense-boned dinosaurs perfectly adapted for freshwater hunting in prehistoric North African river systems. This region was a hotspot for aquatic dinosaur evolution.

Morocco during the Cretaceous period featured extensive river networks that supported diverse aquatic ecosystems. The spinosaurine dental pattern of widely-spaced, unserrated teeth was perfectly designed for gripping slippery prey. Recent discoveries in Morocco have provided nearly complete tail fossils that confirm the advanced swimming capabilities of these dinosaurs. Such specialization would have made Sigilmassasaurus a formidable competitor against any shark species sharing its habitat.

Carcharodontosaurus: The Unexpected Aquatic Giant

While not a spinosaur, Carcharodontosaurus shared habitat with Spinosaurus but was a strictly terrestrial predator with no confirmed swimming adaptations. Evidence from swim tracks proves that various dinosaur species took “watery voyages,” with some specifically hunting fish and other aquatic animals. This suggests even primarily terrestrial predators like Carcharodontosaurus may have been more aquatically capable than previously thought.

Paleontologists have discovered fossilized dinosaur droppings containing fish scales, along with evidence of teeth specialized for aquatic prey. Swim tracks show distinctive drag marks preserved in soft sediment where floating dinosaurs’ toes touched the bottom while swimming. The size and power of Carcharodontosaurus would have made it a devastating aquatic predator when circumstances required, potentially outpacing smaller through sheer muscular force.

Conclusion

The prehistoric world was far stranger and more diverse than we ever imagined. These ten dinosaurs represent a complete revolution in our understanding of ancient life, proving that the boundaries between land and sea were much more fluid sixty-six million years ago. Each new discovery reveals how far we still are from fully understanding these animals and how much we’ve underestimated the ecological breadth of non-avian dinosaurs.

From Spinosaurus with its pressure-sensing snout to Baryonyx with its fishing claws, each species developed unique solutions to aquatic hunting that modern never achieved. These weren’t accidents of evolution – they were precision-engineered swimming machines that dominated ancient waterways through superior adaptations.

What do you think about these aquatic dinosaurs outperforming ? Tell us in the comments which prehistoric swimmer surprised you most!