You might think climate change is purely a modern concern, something we’ve only started grappling with in recent decades. That’s not quite right, though. Long before factories and automobiles, the climate of North America was undergoing wild swings that transformed entire ecosystems and human societies. What happened to the towering mammoths? Why did thriving cities vanish into dust?

Archaeologists have long been concerned about the effects of past climatic events, especially how these events may have influenced human decision-making processes. The stories these ancient shifts tell us are fascinating, unsettling, and surprisingly relevant today. Let’s dive in.

It Created a Bridge Between Continents

Because so much water was piled up on land in ice sheets, the sea level was about 350 feet lower at the peak of the last ice age about 20,000 years ago. The lowered sea exposed a wide plain between Siberia and Alaska, creating a land bridge across the Bering Sea. This wasn’t just any strip of land. It was a highway for humanity itself.

Genetic, linguistic, and fossil evidence suggests that the first humans in America came from northeast Asia, and it is likely that they walked across the land bridge between Siberia and Alaska sometime during the last ice age. Without the ice age locking up ocean water, North America might have remained uninhabited by humans for thousands more years. Climate, in this case, literally opened the door to an entire hemisphere.

It Wiped Out Ice Age Giants

Picture enormous ground sloths lumbering through ancient forests, saber-toothed cats stalking herds of woolly mammoths, and giant beavers the size of bears. These and a variety of other species all became extinct about 10,000 years ago. The debate over what killed them still rages among scientists today.

Megafauna populations appear to have been increasing as North American began to warm around 14,700 years ago. But we then see a shift in this trend around 12,900 years ago as North America began to drastically cool, and shortly after this we begin to see the extinctions of megafauna occur. Some argue humans hunted them to death. Others point to the changing climate. Honestly, it was probably both working in tandem. Given the large amount of megafauna in the northeast, and the lack of evidence for human involvement in their demise, they argue that overkill cannot have been the only or even the major factor for continent-wide extinctions: Climate and environmental stresses must have also played a key role.

It Transformed the Great Basin Into a Desert

Today, the Great Basin between the Cascade Range and the Rocky Mountains is a dry, arid expanse of sagebrush and salt flats. During the ice age it was a wetter place. About 15,000 years ago the Great Salt Lake in Utah was about 1,200 feet deeper and covered an area about the size of Lake Michigan.

Imagine that shift. A massive inland sea gradually shrinking away. As the ice melted and the climate warmed, the west became the relatively dry region we know today. The people and animals that depended on those waters had to adapt or relocate. This drying trend fundamentally reshaped the landscape and made survival in the region far more challenging.

It Forced Forests to Migrate Thousands of Miles

Trees can’t exactly pick up and walk, yet they moved. Spuce trees, which like colder climates, retreated northward by about a thousand miles, giving way to grassland and broadleaf trees. As temperatures rose following the Ice Age, entire forests essentially migrated, shifting their ranges over generations.

This wasn’t just botanical shuffling. Many large mammals like the Mastodon that preferred cold climates were not able to adjust to these changes. When your food source or habitat suddenly disappears over the horizon, survival becomes nearly impossible. The vegetation changes rippled through the food chain, reshaping ecosystems across the continent.

It Triggered Cultural Revolutions Among Indigenous Peoples

The team found that nearly all of the transitions between one cultural period and the next occurred at times of ecological and environmental changes. This isn’t coincidence. When the environment shifts dramatically, people have to rethink everything: where they live, what they eat, and how they organize their societies.

Thus the Paleoindian period, 13,500 to 11,250 years ago, was characterized by the presence of cold-adapted plants such as sedges and spruce and pine trees; the so-called Early Archaic period, 11,250 to 8200 years ago and corresponding to warmer climes, saw a decrease in pine and an increase in oak trees; and 8200 years ago, when another, short cold spell hit much of the world, prehistoric humans underwent another cultural shift known as the Middle Archaic period. Each climate shift brought new challenges and opportunities, forcing communities to innovate or relocate. The authors don’t claim that climate change directly drove cultural change, but they do argue that prehistoric humans periodically “adjusted their tool kits” in response to climate changes.

It Caused the Collapse of the Ancestral Puebloans

The cliff dwellings of Mesa Verde and the grand structures of Chaco Canyon are hauntingly beautiful. They’re also abandoned. Then suddenly, around 1250 AD, they vanished. Well, not vanished exactly. They migrated, leaving behind their architectural marvels.

From 1276 to 1299, the infamous Great Drought devastated the region, lasting an agonizing 300 years. That’s no ordinary dry spell. Current scholarly consensus is that Ancestral Puebloans responded to pressure from Numic-speaking peoples moving onto the Colorado Plateau, as well as climate change. Crops failed, water sources dried up, and entire communities were forced to seek refuge elsewhere. The drought didn’t just inconvenience them. It fundamentally reshaped the Southwest.

It Destroyed North America’s Largest Prehistoric City

Cahokia was first occupied in 700 ce and flourished for approximately four centuries (c. 950–1350). It reached a peak population of as many as 20,000 individuals and was the most extensive urban center in prehistoric America north of Mexico and the primary center of the Middle Mississippian culture. It rivaled European cities of the same era.

Then it crumbled. Climate change in the form of back-to-back floods and droughts played a key role in the 13th century exodus of Cahokia’s Mississippian inhabitants. Imagine your city flooded one decade and drought-stricken the next. The lake core showed that summer precipitation likely decreased around the onset of Cahokia’s decline. This could have affected the ability of people to grow their staple crop maize. The population scattered, abandoning their monumental earthworks to the elements.

It Shaped the Rise and Fall of Medieval Warm Period Societies

Chaco Canyon in New Mexico, Cahokia near St. Louis, and Casas Grandes in northern Chihuahua rose during the warm and moist years of the Medieval Warm Period. With the onset of the Little Ice Age around A.D. 1300, these centers faced a marked decline in population and agricultural production. Climate wasn’t just a background factor. It was a driving force.

Warmer, wetter conditions allowed agriculture to thrive, cities to expand, and cultures to flourish. When that window closed and colder, drier conditions set in, those same societies struggled to adapt. The major centers collapsed, as did dozens of smaller towns. It’s hard to say for sure whether they could have survived with different strategies, but the climate shift was undeniably brutal.

It Created Megadroughts That Reshaped the Southwest

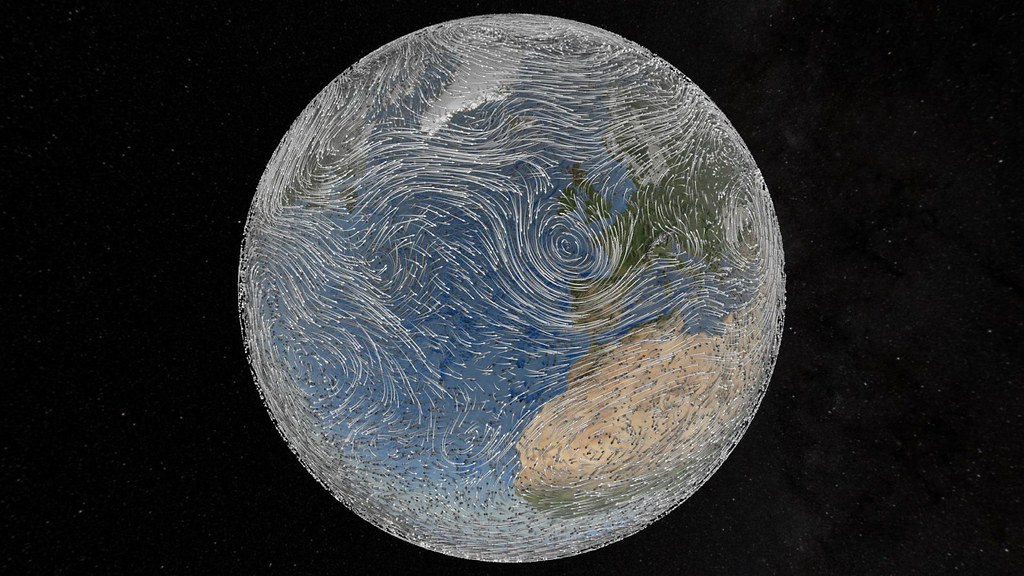

These simulations revealed that early Holocene droughts were influenced by high-pressure systems associated with lingering ice sheets, which shifted moisture patterns. As the ice sheets melted, rising summer temperatures further intensified drying across the continent. These weren’t droughts lasting a couple of seasons. They lasted decades, even centuries.

The study suggests that as current climate change progresses, North America could again face extensive drying, despite potentially increased rainfall, due to higher evaporation rates driven by warming temperatures. The past might be prologue. Ancient megadroughts forced mass migrations and societal collapses. What will modern megadroughts do to our own civilization?

It Altered the Course of Viking Settlement Attempts

Vikings reached North America centuries before Columbus, establishing settlements in places like Greenland and Newfoundland. The first Europeans to set foot on America were Vikings who settled Greenland under the leadership of Eric the Red in about 1000AD. His son, Leif Erikson, led an expedition to colonize America that probably settled in Newfoundland.

The Greenland colony didn’t last, though. The colony in Greenland was abandoned in about 1400AD when cooler temperatures associated with the Little Ice Age made farming there too difficult. They couldn’t grow enough food to survive as temperatures dropped. Climate didn’t just challenge ancient Native American societies; it also pushed European settlers off the continent for centuries.

Conclusion: Climate as the Silent Architect

Climate change has been shaping North America’s story for thousands of years. It built bridges between continents, toppled empires, erased species, and forced entire civilizations to pack up and move. The ancient peoples of North America weren’t passive victims. They adapted, innovated, and survived countless environmental upheavals.

Yet sometimes, the changes were just too much. The lesson here isn’t about doom and gloom. It’s about understanding how profoundly climate shapes everything we are and everything we build. Our ancestors faced these challenges without weather satellites, climate models, or global supply chains. What does that tell us about our own resilience, or lack thereof? Did you expect that climate played such a powerful role in shaping the continent’s ancient history?