While paleontologists and researchers often receive the spotlight for groundbreaking fossil discoveries, the meticulous work of laboratory technicians and fossil preparators remains largely in the shadows. These skilled professionals transform raw field specimens into scientifically valuable artifacts through painstaking preparation, preservation, and documentation. Their expertise combines artistry with scientific precision, yet their names rarely appear in headlines or museum placards. The following five individuals represent countless technicians whose behind-the-scenes contributions have fundamentally advanced our understanding of prehistoric life. Their stories highlight the critical importance of technical expertise in paleontological research and demonstrate how these dedicated professionals often develop innovations that change the entire field.

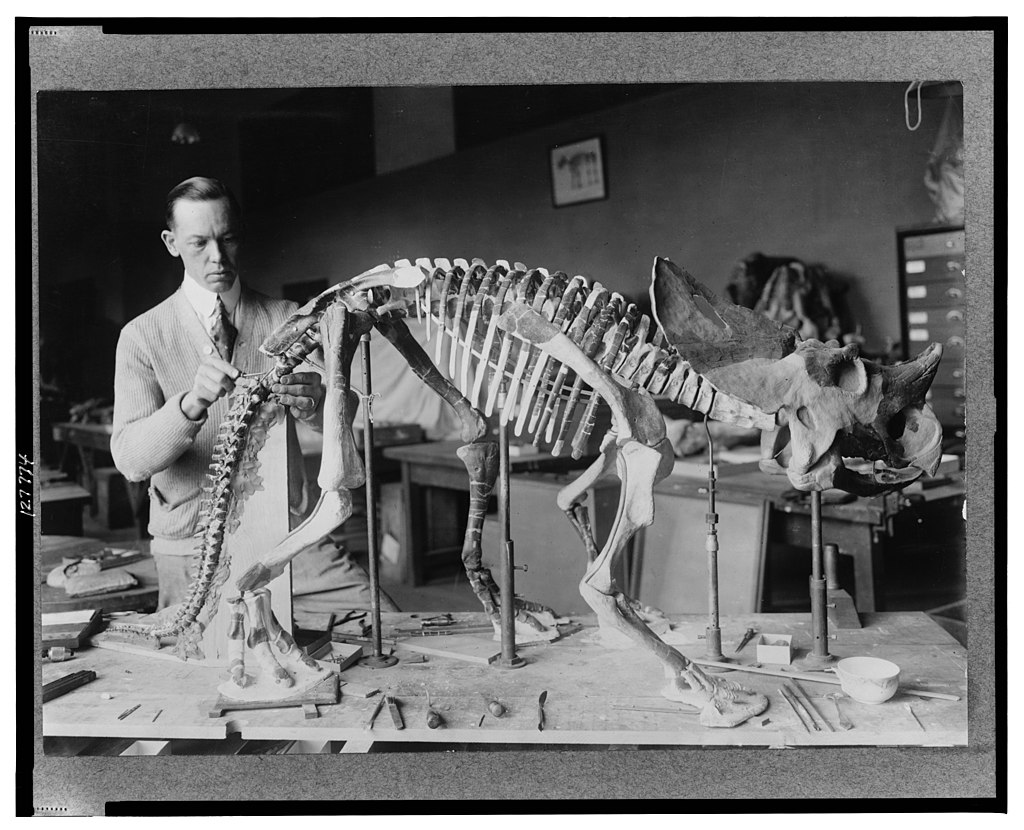

Norman Ross: The Dinosaur Doctor of the American Museum of Natural History

Norman Ross served as the chief preparator at the American Museum of Natural History from 1911 to 1941, during what many consider the golden age of dinosaur discoveries. Working closely with renowned paleontologist Barnum Brown, Ross developed revolutionary techniques for fossil preparation that are still used today. His most significant contribution was perfecting a method for removing matrix rock from delicate fossils using pneumatic tools adapted from dentistry equipment. Ross personally prepared many of the most iconic dinosaur specimens on display at the AMNH, including the first mounted Tyrannosaurus rex skeleton. Despite his crucial role in preserving these specimens, Ross’s name appears in few scientific papers and museum exhibits. His meticulous notes on preparation techniques, however, trained generations of preparators and established standards that transformed the field of vertebrate paleontology.

Ione Fassett: The Woman Who Preserved the La Brea Tar Pits

Ione Fassett joined the staff at the La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles in 1924, becoming one of the first female fossil preparators in America. Her groundbreaking work involved developing methods to clean and preserve fossils recovered from the uniquely challenging asphalt deposits. Fassett pioneered techniques using organic solvents to remove sticky tar without damaging delicate bone structures, an innovation that made possible the scientific study of thousands of Ice Age specimens. Over her 32-year career, she personally prepared more than 10,000 fossils, including many of the most impressive specimens still on display at the La Brea Tar Pits Museum. Despite her technical innovations and incredible productivity, Fassett rarely received formal recognition in scientific publications. Her detailed preparation logs, however, continue to provide invaluable data for researchers studying taphonomy and preservation in tar pit environments.

Vincenzo Fusco: The Master Artisan of Bolca

Working in the limestone quarries near Bolca, Italy during the mid-20th century, Vincenzo Fusco developed unparalleled skill in preparing the exquisitely preserved Eocene fish fossils for which the region is famous. Unlike institutional preparators, Fusco was largely self-taught, beginning his career as a quarry worker before developing specialized techniques for revealing the incredibly detailed fish fossils embedded in the fine-grained limestone. His innovation came in the form of specially designed micro-tools and a technique involving alternating applications of dilute acid and neutralizing solutions that allowed unprecedented detail to be revealed. Fusco prepared specimens now housed in major museums worldwide, including several type specimens used to describe new species. Though his name rarely appears in scientific literature, paleontologists specializing in fossil fish universally acknowledge that Fusco’s preparation skills revealed anatomical details that would otherwise have remained hidden, significantly advancing our understanding of fish evolution.

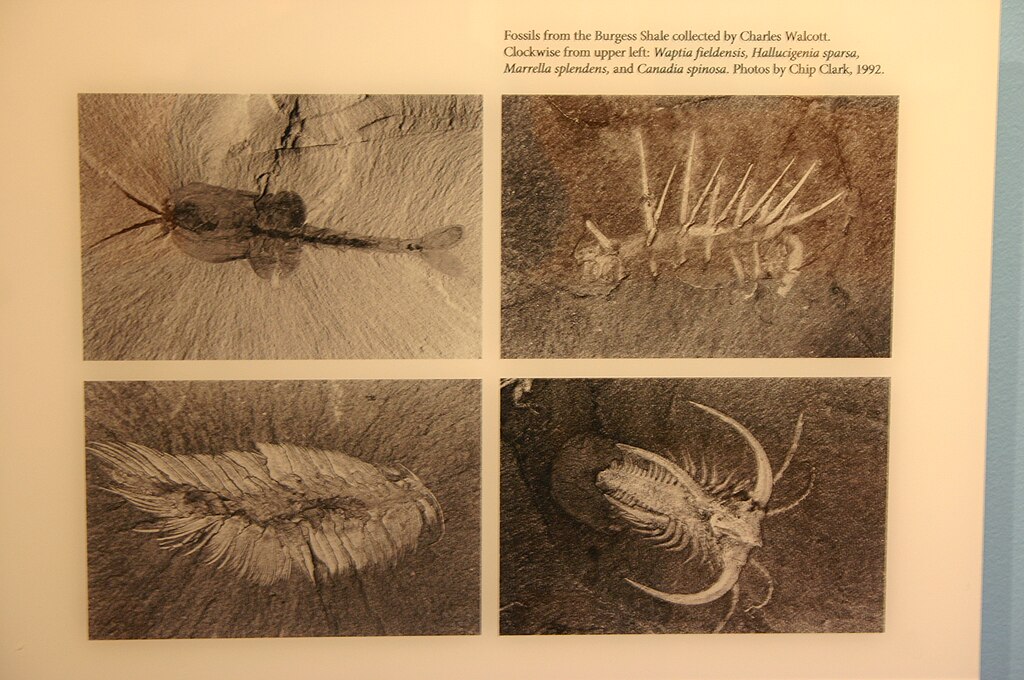

Gladwyn Sullivan: The Technician Behind the Burgess Shale Revolution

The Burgess Shale fossils represent one of paleontology’s most important discoveries, preserving soft-bodied creatures from the Cambrian explosion over 500 million years ago. When paleontologist Harry Whittington began his landmark reanalysis of these specimens in the 1960s, he relied heavily on the technical expertise of Gladwyn Sullivan, a preparator at Cambridge University. Sullivan developed specialized photographic techniques that revealed previously unseen details in these flattened fossils, including using polarized light and various enhancement methods that made faint impressions visible. These technical innovations proved crucial to reinterpreting bizarre creatures like Opabinia and Hallucigenia, fundamentally changing our understanding of early animal evolution. While Whittington and colleagues Stephen Jay Gould and Derek Briggs received scientific recognition for the revolutionary interpretations, Sullivan’s technical contributions that made these insights possible remained largely uncredited outside specialist circles.

Mei Yangfeng: The Preservation Pioneer of Liaoning

The spectacularly preserved feathered dinosaurs and early birds from China’s Liaoning Province have transformed our understanding of dinosaur-bird evolution over the past three decades. Behind many of these remarkable specimens is the preparation work of Mei Yangfeng, who joined the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing in the early 1990s. Mei developed specialized techniques for preparing the delicate fossils from the finely laminated lake sediments, including methods to stabilize the often fragile feather impressions. Her most significant innovation was a transfer preparation technique that allowed both sides of split fossils to be studied and preserved, effectively doubling the information available from each specimen. Though rarely mentioned in scientific papers describing the headline-making discoveries, Mei has prepared dozens of type specimens that defined new species of feathered dinosaurs. Her technical protocols for Liaoning fossil preparation have been adopted by institutions worldwide working with similar preservation conditions.

The Critical Role of Laboratory Technicians in Paleontology

Laboratory technicians in paleontology occupy a unique position that bridges fieldwork and research. Their work begins where excavation ends, with specimens often arriving encased in protective plaster jackets or embedded in matrix rock. The preparation process requires removing this surrounding material while stabilizing the often fragile fossil underneath—work that demands both technical skill and anatomical knowledge. A preparator must make countless decisions that affect a specimen’s scientific value, determining which features to emphasize and how to preserve structures for future study. This process can take months or even years for complex specimens, with preparators documenting each step and sometimes making discoveries that field paleontologists missed. Modern preparators also incorporate cutting-edge technologies like CT scanning to guide their work, blending traditional craftsmanship with scientific innovation in ways that fundamentally shape our access to the prehistoric world.

The Art and Science of Fossil Preparation

Fossil preparation exists at the intersection of art and science, requiring technical precision guided by scientific understanding. Preparators must possess intimate knowledge of comparative anatomy to recognize important structures as they emerge from the rock. They must also understand the physical and chemical properties of both the fossil material and surrounding matrix to select appropriate tools and techniques. Preparation involves an arsenal of implements ranging from dental picks and airscribes to precision air abrasives and chemical treatments. The best preparators develop an intuitive feel for their materials, knowing exactly how much pressure to apply or which solvent will dissolve matrix without damaging bone. This specialized knowledge often remains tacit rather than formalized, passed from experienced preparators to apprentices through direct mentorship. The field continues to advance through innovation, with techniques like acid preparation, ultraviolet light examination, and CT-guided preparation expanding what’s possible in revealing ancient life forms.

The Gender Dimension in Preparation Work

The history of fossil preparation reflects broader gender dynamics in science, with women often channeled into technical roles rather than research positions. Beginning in the early 20th century, many museums employed female preparators, considering their supposedly “natural” patience and manual dexterity well-suited to detailed preparation work. While these gender assumptions were problematic, they created employment opportunities for women in paleontology at a time when research positions remained largely closed to them. Many female preparators, like Ione Fassett, developed significant technical innovations despite limited formal scientific training. This pattern persisted throughout much of the 20th century, with preparation labs often employing more women than research departments. Today, while the field has become more balanced, the historical contributions of female preparators remain underrecognized in the scientific literature. Their stories represent an important chapter in the broader history of women in science, highlighting how technical roles often provided pathways to scientific contribution when more direct routes were unavailable.

Changing Recognition Patterns in Modern Paleontology

The traditional model of scientific credit in paleontology has historically focused on field collectors and research scientists, leaving preparators underrepresented in publications and public recognition. This paradigm has begun shifting in recent decades, with more institutions acknowledging the intellectual contributions of preparation staff. Modern scientific papers increasingly include preparators as co-authors when their technical work substantially contributes to research findings. Museums have also started featuring preparation labs with viewing windows that allow visitors to watch technicians at work, highlighting their crucial role in the scientific process. Professional organizations like the Association for Materials and Methods in Paleontology now provide formal platforms for preparators to share techniques and receive recognition from peers. These changes reflect growing recognition that preparation work involves not just technical execution but scientific judgment and discovery that fundamentally shapes research outcomes.

The Challenges of Modern Fossil Preparation

Today’s fossil preparators face unique challenges that their predecessors could hardly have imagined. The increasing rarity of accessible fossil sites means that each specimen carries greater scientific importance, amplifying the pressure to maximize information recovery during preparation. Preparators must now balance traditional mechanical preparation with preservation for future analytical techniques that may not yet exist. Modern preparation labs increasingly incorporate cutting-edge technologies like micro-CT scanning to guide preparation decisions, allowing visualization of internal structures before they’re exposed. Chemical analysis has become a standard part of preparation protocols to ensure compatibility between stabilizing compounds and future research methods. Perhaps most challenging is the need to document everything digitally, creating comprehensive records that future researchers can access. These evolving demands require today’s preparators to continuously update their skills and knowledge, transforming what was once considered a purely technical role into a sophisticated scientific specialty requiring extensive training and ongoing professional development.

The Legacy of Innovation in Preparation Techniques

Throughout paleontology’s history, many of the most significant technical innovations have emerged from preparation laboratories rather than research departments. Norman Ross’s adaptation of dental tools for fossil preparation in the early 20th century revolutionized the field’s capabilities, allowing the recovery of delicate structures previously impossible to extract from matrix rock. In the 1940s, preparators at various institutions pioneered acid preparation techniques that made possible the study of microscopic fossils like conodonts. The 1970s saw preparation staff developing specialized methods for electron microscope studies, revealing previously invisible details of ancient organisms. More recently, preparators have developed protocols for CT-guided preparation that allow virtual examination of fossils before physical preparation begins. These innovations highlight how technical staff often drive methodological advances in paleontology, creating new research possibilities through their practical problem-solving. The history of paleontological methods cannot be separated from the contributions of these skilled technicians who have repeatedly expanded the boundaries of what researchers can observe and study.

The Educational Pathways of Fossil Preparators

Unlike academic paleontologists who follow relatively standardized educational paths through doctoral programs, fossil preparators enter the field through diverse routes that combine formal education with apprenticeship. Historically, many preparators began as artists, skilled craftspeople, or field assistants who learned through direct mentorship from experienced technicians. Today, while some institutions offer specialized training programs in fossil preparation, most professionals still develop their skills through a combination of formal coursework and extended apprenticeship. Educational backgrounds among preparators vary widely, from fine arts and sculpture to geology, biology, and conservation science. This diversity of backgrounds contributes to innovation in the field, as preparators bring techniques and perspectives from different disciplines. The apprenticeship model remains essential because many crucial skills—like developing the “feel” for different types of fossil material—can only be acquired through guided practice. This educational pattern highlights the unique position of preparation work as a specialized craft that serves scientific ends, requiring both technical mastery and scientific understanding.

Conclusion: Recognizing the Hands Behind the Fossils

The stories of Norman Ross, Ione Fassett, Vincenzo Fusco, Gladwyn Sullivan, and Mei Yangfeng represent just a small sample of the countless technicians whose skilled hands have shaped our understanding of prehistoric life. Their contributions remind us that paleontology is not just a science of discovery but also of recovery—the painstaking process of revealing information preserved in stone. As museums and research institutions increasingly acknowledge the crucial role of preparation work, we gain a more complete picture of how paleontological knowledge is produced through collaboration across specialties. The next time you marvel at a perfectly preserved fossil in a museum display, consider not just the ancient organism and the scientist who studied it, but also the skilled hands that carefully freed it from stone, making its story accessible to science and the public alike. These unsung heroes deserve recognition as essential contributors to our understanding of life’s deep history.