Think you know what made ancient predators deadly? It wasn’t always just brute strength or massive teeth. Sure, the Ice Age had its share of terrifying creatures, but what’s genuinely fascinating is how smart these animals actually were.

Picture this: animals coordinating ambushes, using tools of sorts, and even demonstrating strategic thinking that rivals modern predators. We often imagine prehistoric hunters as simple killing machines, but the reality is far more intriguing. The tactics these creatures employed were refined over millions of years of evolution, creating hunting strategies that would make even today’s apex predators take notice.

Saber-Toothed Cats: Precision Killers With a Twist

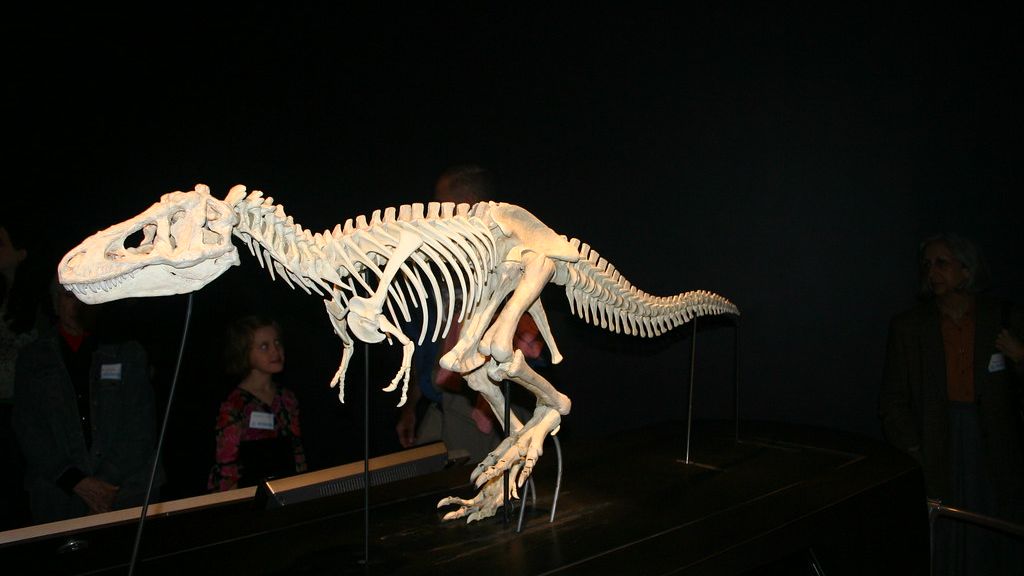

Saber-toothed cats had surprisingly weak jaws but extremely strong neck muscles, which completely changes our understanding of how they hunted. Imagine a predator whose bite was three times weaker than a modern lion’s, yet it successfully dominated its ecosystem for millions of years. Here’s the thing: those iconic fangs weren’t meant for crushing at all.

These cats ambushed large prey using powerful back and forelimb muscles to pull down and position the animals for killing bites. Instead of the chase-and-bite strategy we see in modern big cats, they operated more like precision assassins. Sabertooths were probably ambush predators with strong forelimbs and necks, subduing prey with their forelimbs and driving sabers into the flesh with their neck muscles.

The most shocking part? When subjected to the same forces a lion handles easily, the entire skull of a saber-tooth experienced tremendous stress and strain, risking snapping teeth or skull if it tackled large prey still on their feet. They had to completely immobilize their victims first. Injured cats ate softer foods, likely a higher proportion of flesh, fat and organs, and allowed each other access to food when injured pack members couldn’t take down their own prey, suggesting these fearsome predators actually displayed social cooperation and care.

Terror Birds: Axe-Wielding Avian Nightmares

If you thought prehistoric birds were harmless, think again. Terror birds were large carnivorous, mostly flightless birds that were among the largest apex predators in South America during the Cenozoic era, ranging in height from 1 to 3 meters, with the largest specimens weighing up to 350 kilograms. Let’s be real, a ten-foot-tall bird with a beak like a battle axe is nightmare fuel.

Their hunting method was downright brutal yet ingenious. When the victim was at close range, phorusrhacids killed by striking using their large beaks as axes, with precise repeated vertical strikes. Picture a predator that doesn’t bite down like typical animals but instead hammers its prey to death with calculated blows. The terror bird had a highly flexible and developed neck allowing it to carry its heavy head and strike with terrifying speed and power, with developed neck muscles and heavy head producing enough momentum to cause fatal damage.

These birds didn’t just rely on speed. Phorusrhacids may have used ambush tactics to approach prey, as their large and tall forms would be easy to identify from a distance. Scientists theorize that the large terror birds were extremely nimble and quick runners, able to reach speeds of 48 km/h. The combination of ambush strategy, incredible striking power, and decent speed made them virtually unstoppable in their ecosystem.

Dire Wolves: Pack Intelligence Over Individual Strength

Wolves, dingoes, and painted dogs are known for running large prey down over long distances, with all three species inflicting bites to further weaken the animal over the course of the hunt. Dire wolves, the now-extinct cousins of modern gray wolves, took pack hunting to another level entirely. These weren’t the fictional beasts from television but real predators with serious strategy.

Dire wolves were more likely to suffer from injuries to the head, neck, ankles and wrists, with neck injuries clustered together that could have resulted from wolves being dragged by thrashing prey. This tells us something profound: they were willing to take hits as a team. Unlike the saber-toothed cats that avoided head injuries at all costs, dire wolves put themselves in harm’s way because they hunted cooperatively.

Canids pant when hot, which has the double effect of cooling the animal via evaporation of saliva while also increasing the amount of oxygen absorbed by the lungs. This adaptation gave them endurance advantages that allowed for persistence hunting strategies. It wasn’t just about being fast in short bursts but about wearing down prey over time through coordinated attacks and relentless pursuit.

Komodo Dragons: The Venom-Tracking Combo

Modern Komodo dragons give us insight into how ancient monitor lizards might have hunted, and honestly, it’s both fascinating and terrifying. Varanid lizards possess a unique heart structure that allows them to run faster over longer distances than other lizards, and they utilize a forked tongue to track injured prey over large distances after a failed ambush, with several species also utilizing venom to ensure the death of their prey.

Think about the sophistication here. These aren’t mindless biters hoping to get lucky. They combine initial ambush attacks with a backup plan: if the prey escapes, the venom ensures it won’t get far, and that forked tongue becomes a GPS system for tracking. The cardiovascular adaptations mean they don’t tire out during pursuit either.

This hunting strategy represents a remarkable evolutionary innovation. Rather than committing fully to either ambush or pursuit tactics, these lizards developed a hybrid approach that maximized success rates. The venom doesn’t kill immediately but weakens the prey over time, making the eventual takedown far easier.

Ancient Crocodilians: Masters of the Calculated Ambush

Living crocodilians and carnivorous turtles are specialized ambush predators and rarely if ever chase prey over great distances. Their prehistoric relatives perfected this strategy to an art form. Ancient crocodiles launched ambush attacks from bodies of water, and a Homo habilis individual dubbed OH8 may have fallen victim to such an attack 1.8 million years ago, with bone damage matching that characteristic of a crocodile attack, losing half of its left foot.

What makes crocodilian hunting so sophisticated isn’t flashiness but patience and precision. These predators could wait motionless for hours or even days, conserving energy while monitoring their surroundings. When the moment arrived, the explosive power of their attack gave prey almost no chance of escape.

The calculation involved is remarkable. Crocodiles had to assess water depth, prey size, and approach angles perfectly. One miscalculation meant going hungry, so evolutionary pressure refined these ambush skills over millions of years. Modern crocodiles still use nearly identical tactics, proof that this hunting strategy achieved near-perfection long ago.

Early Hominins: Intelligence as the Ultimate Weapon

Here’s where things get really interesting. Foragers thrived in tropical grasslands by either adopting fast hunting strategies requiring sophisticated hunting tools or by cooperating extensively relying on enhanced social structure to promote cooperative behavior. Our ancient ancestors weren’t the strongest or fastest, but they might have been the smartest.

Ancient human hunters likely waited in brushy, forested areas for animals to pass by and may have even hidden in the branches of trees since hooved animals tend not to look up, relying more on smarts than persistence, getting close enough to club the animal with a sharp object. That’s tactical thinking on a level most predators never reached. Using height advantage and exploiting prey behavior patterns shows genuine strategic planning.

The first experimental study on how stone weapons like Clovis points might react to the force of an approaching animal revealed that the spear tip behaved like a modern hollow-point bullet, causing serious damage to creatures such as mastodons, bison, and saber-toothed cats. Think about that: ancient humans engineered weapons with ballistic properties. The Levallois technique required craftsmen to prepare a core of good-quality stone then cut a pointed item off with one stroke, a process requiring them to imagine the final outcome in advance, and stone tips made with this technology appeared simultaneously with a relative decrease in large prey bones.

Giant Hyenas: Opportunistic Geniuses

Predators like saber-toothed cats dominated the food chain, and our ancestors and their relatives may have frequently relied on scavenging their felled prey, with models suggesting hominins were most successful when banding together to exploit and defend such finds from adversaries like giant hyenas seeking their own easy meals. Giant hyenas weren’t just scavengers waiting for leftovers. They were strategic competitors who understood resource value.

Scavenging may have required some pretty sophisticated behavior, cognition and communication, challenging our assumptions about intelligence in ancient predators. These animals had to rapidly assess carcass value, determine if they could successfully defend or steal it, and coordinate with pack members. The social intelligence required rivals that of active hunters.

Saber-toothed cats didn’t pick carcasses clean and routinely left lots of meat on the bone, representing nourishing meals for the taking. Giant hyenas specialized in exploiting this niche, developing powerful jaws capable of crushing bones that other predators left behind. They essentially created a secondary food chain by maximizing resource extraction from kills made by others. That’s not lazy scavenging; that’s ecological genius.

Conclusion

The ancient world was far more complex than we usually give it credit for. These predators weren’t just mindless eating machines driven by instinct alone. They developed hunting tactics that required planning, cooperation, specialized anatomy, and genuine problem-solving abilities. From the precision neck strikes of saber-toothed cats to the tool-making ingenuity of early hominins, sophistication defined survival.

What’s truly remarkable is how different species arrived at completely different solutions to the same problem: how to eat without being eaten. Some chose brute force engineering like terror birds, others selected patient ambush strategies like crocodilians, while still others relied on social cooperation and persistence. Each strategy was refined over countless generations into something approaching perfection for its ecological niche.

The next time you see a nature documentary about modern predators, remember they’re standing on millions of years of evolutionary experimentation. The sophisticated tactics we observe today didn’t appear from nowhere. They’re the refined descendants of strategies first tested by these ancient hunters. Did you expect prehistoric predators to be this clever?