The Late Cretaceous period, just before the mass extinction event that wiped out non-avian dinosaurs approximately 66 million years ago, was home to some of the most fascinating and formidable dinosaurs that ever walked the Earth. While many people are familiar with Tyrannosaurus rex, numerous other remarkable species roamed the planet during these final chapters of dinosaur dominance. These dinosaurs had evolved specialized adaptations and diverse lifestyles, representing the culmination of millions of years of evolutionary refinement. In this article, we’ll explore nine incredible dinosaurs that witnessed the twilight of the Mesozoic Era, offering a glimpse into the rich biodiversity that existed just before one of the most significant extinction events in Earth’s history.

Tyrannosaurus Rex: The Iconic Apex Predator

No discussion of Late Cretaceous dinosaurs would be complete without mentioning Tyrannosaurus rex, perhaps the most famous dinosaur of all time. T. rex lived approximately 68-66 million years ago in what is now western North America, making it one of the last dinosaur species to exist before the extinction event. These massive theropods could reach lengths of up to 40 feet and weigh around 9 tons, with powerful jaws that could exert a bite force of up to 12,800 pounds. Recent research suggests T. rex was not merely a scavenger but an active predator with binocular vision and a remarkable sense of smell. Studies of growth rings in T. rex bones indicate that these animals experienced a dramatic growth spurt during adolescence, gaining up to 4.6 pounds per day during their teenage years. Despite their fearsome reputation, paleontologists now believe T. rex may have been a caring parent, potentially guarding their nests and providing food for their young.

Triceratops: The Three-Horned Giant

Triceratops, recognizable by its three facial horns and large bony frill, was one of the last dinosaurs to evolve before the extinction event, living between 68 and 66 million years ago. These massive herbivores could grow up to 30 feet long and weigh approximately 12 tons, making them formidable even to predators like T. rex. The purpose of their distinctive frill and horns has been debated among scientists, with theories including defense against predators, species recognition, and competition for mates. Triceratops traveled in herds, offering protection against predators through their sheer numbers and defensive capabilities. Recent fossil discoveries have revealed that Triceratops continued to evolve rapidly even in the final million years before extinction, with variations in horn and frill structures appearing across different populations. Their robust beaks and specialized teeth allowed them to process tough, fibrous plant material that was common in the late Cretaceous landscape.

Ankylosaurus: The Living Tank

Ankylosaurus magniventris was one of the most heavily armored dinosaurs of all time, living between 68 and 66 million years ago in western North America. This herbivore’s body was covered in bony plates called osteoderms, and it wielded a massive tail club that could have delivered devastating blows to predators. Recent studies indicate that a well-placed swing from an Ankylosaurus’ tail club could potentially break bones, making it a formidable defensive weapon against even large theropods. Growing up to 20 feet long and weighing approximately 8 tons, Ankylosaurus was a slow-moving but well-protected animal that likely had few natural predators as an adult. The intricate arrangement of its armor plates not only provided protection but may have also played a role in thermoregulation, helping to control body temperature. Ankylosaurus’s wide muzzle suggests it was a low-browsing herbivore, feeding on vegetation close to the ground rather than reaching for higher foliage.

Alamosaurus: The North American Titan

Alamosaurus sanjuanensis was one of the last sauropod dinosaurs in North America, living during the final few million years of the Cretaceous period. This massive herbivore could reach lengths of 70-80 feet and weigh up to 80 tons, making it one of the largest land animals alive just before its extinction. Unlike earlier sauropods that had largely disappeared from North America, Alamosaurus appears to have migrated from South America across land bridges that formed during the Late Cretaceous. Its massive size would have offered protection against predators like Tyrannosaurus, though juvenile Alamosaurus would have been vulnerable. The long neck of Alamosaurus allowed it to reach vegetation high in the canopy, accessing food sources unavailable to other herbivores. Interestingly, fossil evidence suggests that Alamosaurus continued to grow throughout its life, with the largest specimens representing individuals of considerable age.

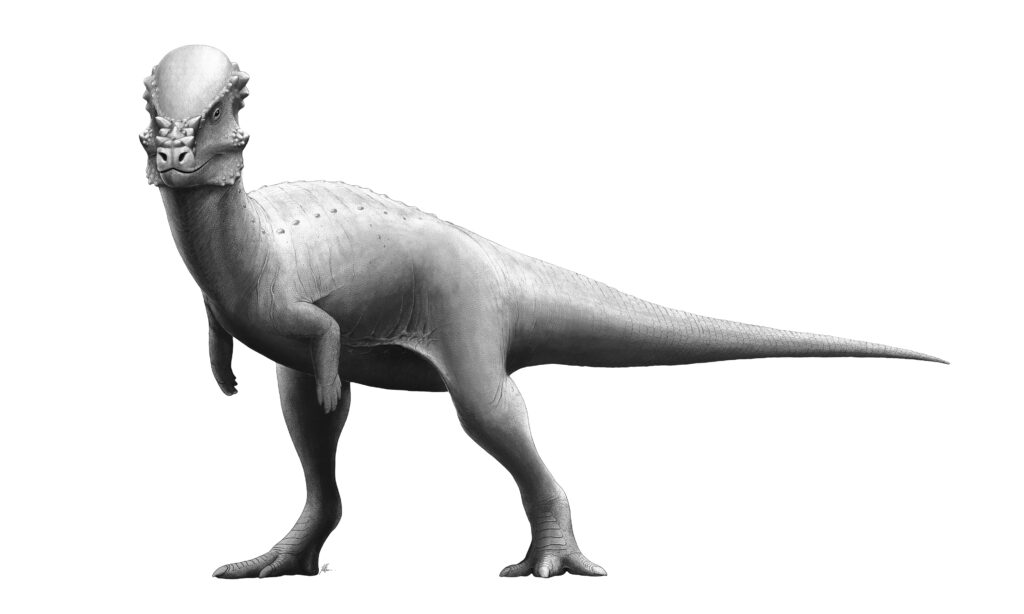

Pachycephalosaurus: The Dome-Headed Enigma

Pachycephalosaurus wyomingensis, known for its distinctive domed skull, was one of the last ornithischian dinosaurs, living between 70 and 66 million years ago. The thick bone dome on its head, reaching up to 10 inches in thickness, has long puzzled paleontologists regarding its function. Current research suggests these domes were likely used in headbutting contests between males competing for mates, similar to behaviors seen in modern bighorn sheep. CT scans of pachycephalosaur skulls reveal complex internal structures that could have absorbed impact forces during such contests. Growing up to 15 feet long, Pachycephalosaurus was a bipedal omnivore that likely consumed both plants and small animals. Remarkably, juveniles had flat heads with small nodes and spikes, which gradually developed into the distinctive dome as they matured, suggesting dramatic changes throughout their life cycle. Recent fossil discoveries have revealed that the diversity of dome-headed dinosaurs was greater than previously thought, with several species coexisting in the late Cretaceous ecosystems.

Quetzalcoatlus: The Pterosaur Giant

While technically not a dinosaur but a pterosaur, Quetzalcoatlus northropi shared the late Cretaceous world with dinosaurs and represents an important component of pre-extinction ecosystems. With a wingspan of up to 36 feet, Quetzalcoatlus was one of the largest flying animals ever to exist, comparable in size to a small airplane. These massive creatures lived between 68 and 66 million years ago, becoming extinct alongside non-avian dinosaurs during the end-Cretaceous event. Once thought to primarily be a soaring scavenger, more recent research suggests Quetzalcoatlus may have been an active predator, using its long beak to probe for prey in soil or shallow water. Biomechanical studies indicate that despite its enormous size, Quetzalcoatlus could take off under its power using a quadrupedal launch technique, pushing off with its powerful forelimbs before transitioning to wing-powered flight. Evidence from bone scans suggests these animals had extremely lightweight skeletons with air-filled bones, allowing them to achieve their remarkable size while remaining airborne.

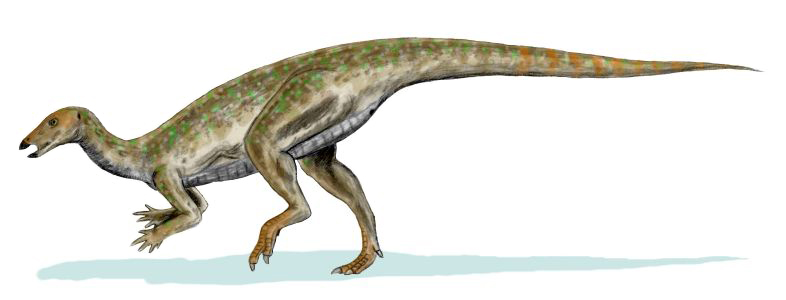

Thescelosaurus: The “Wonderful Lizard” That Almost Survived

Thescelosaurus neglectus has gained recent fame as the subject of an extraordinary fossil nicknamed “Dakota,” which some researchers believe preserves actual remnants of soft tissues, including what might be a fossilized heart. Living at the very end of the Cretaceous period, between 68 and 66 million years ago, this small ornithischian dinosaur reached lengths of around 10 feet. Unlike many of its more specialized relatives, Thescelosaurus retained a more primitive body plan, running on two legs and possessing generalized teeth that suggest an omnivorous diet. This adaptability might have helped the species thrive right up until the asteroid impact. Paleontologists have discovered Thescelosaurus specimens with gastroliths (stomach stones) that helped grind plant material in their digestive systems, compensating for their simple dentition. Remarkable specimens have been found with bones articulated in natural positions, suggesting these animals were rapidly buried, possibly providing evidence for the catastrophic nature of the extinction event.

Dakotaraptor: The Giant Plains Dromaeosaur

Dakotaraptor steini was one of the largest dromaeosaurids (“raptors”) ever discovered, living in what is now South Dakota during the very end of the Cretaceous period. At approximately 16-17 feet long, Dakotaraptor was much larger than its famous relative Velociraptor, and represented an apex predator that hunted alongside Tyrannosaurus rex. This recently discovered dinosaur (first described in 2015) possessed the characteristic enlarged sickle-shaped claw on each foot that dromaeosaurids used to subdue prey. Evidence of quill knobs on Dakotaraptor’s forearms indicates it possessed feathers, continuing to strengthen the evolutionary connection between non-avian dinosaurs and birds. Analysis of Dakotaraptor’s limb proportions suggests it was built for speed despite its large size, potentially allowing it to chase down prey in the open environments of the late Cretaceous Hell Creek Formation. The discovery of Dakotaraptor has revolutionized our understanding of the ecosystem that existed just before the extinction, revealing a more complex predator hierarchy than previously recognized.

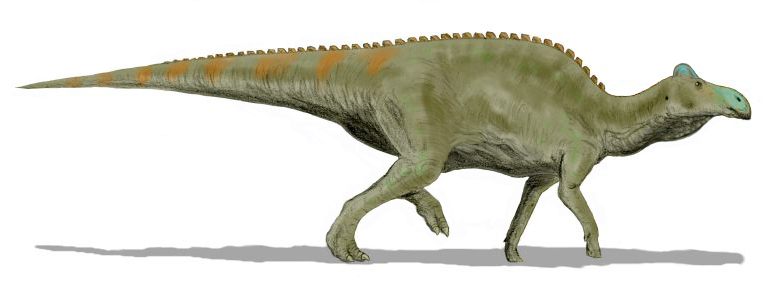

Edmontosaurus: The Duck-Billed Survivor

Edmontosaurus was one of the most successful and widespread dinosaur genera in the final stages of the Cretaceous period, with fossils found across western North America. These large hadrosaurs, or duck-billed dinosaurs, could grow to lengths of 30-40 feet and weigh up to 4 tons, traveling in large herds across the landscape. Remarkably adaptable, Edmontosaurus possessed batteries of hundreds of teeth that were continuously replaced throughout its lifetime, allowing it to process a wide variety of plant materials. Some specimens have been discovered with preserved skin impressions, revealing complex patterns of scales and flexible skin that lacked the bony armor found in many other dinosaur groups. Paleontological evidence suggests Edmontosaurus undertook seasonal migrations, following food sources across hundreds of miles as seasons changed. One famous specimen, nicknamed “Dakota,” was so well-preserved that scientists could examine the muscle structure, revealing that Edmontosaurus was likely faster and more muscular than previously thought.

The Changing Ecosystems of the Late Cretaceous

The final few million years before the extinction event were characterized by dramatic environmental changes that influenced dinosaur evolution and distribution. Sea levels were fluctuating significantly during this period, altering coastal habitats and creating new evolutionary pressures. The climate was cooling gradually from the earlier greenhouse conditions of the Mesozoic, though it remained significantly warmer than today’s climate. Flowering plants (angiosperms) were undergoing a rapid evolutionary radiation, changing the plant communities that supported herbivorous dinosaurs. These changing plant communities likely influenced the diversity and adaptations of herbivorous dinosaurs like hadrosaurs and ceratopsians, which developed increasingly specialized feeding apparatuses. Evidence from fossil sites worldwide suggests dinosaur diversity was still robust in many regions right up until the extinction event, though some studies indicate a potential decline in certain groups. The complex interactions between herbivores and plant communities likely created evolutionary ripple effects throughout dinosaur food webs during this period.

The Chicxulub Impact: End of an Era

Approximately 66 million years ago, an asteroid approximately 6-9 miles in diameter struck Earth in what is now the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico, creating the Chicxulub crater and triggering the mass extinction that ended the reign of non-avian dinosaurs. The immediate effects included massive tsunamis, global wildfires, and an impact winter caused by dust and aerosols blocking sunlight. Recent research from sites like Tanis in North Dakota has uncovered remarkable evidence of the immediate aftermath of the impact, including fossils of fish with impact spherules in their gills, suggesting they died within hours of the asteroid strike. The long-term environmental effects included significant drops in global temperatures, acid rain, and disruption of food chains that relied on photosynthesis. While the impact was the primary driver of extinction, some evidence suggests volcanic activity from the Deccan Traps in India may have already stressed global ecosystems before the asteroid strike. Remarkably, some dinosaur lineages survived—the birds—demonstrating how evolutionary history can take unexpected turns even through catastrophic events.

Legacy and Modern Understanding

The study of the latest Cretaceous dinosaurs continues to evolve with new technologies and fossil discoveries. Advanced techniques like CT scanning, isotope analysis, and molecular paleontology are providing unprecedented insights into how these animals lived, moved, and functioned metabolically. The discovery that some dinosaurs, including many of those mentioned in this article, possessed feathers has revolutionized our understanding of dinosaur physiology and their evolutionary relationship to birds. Paleoartists now depict many dinosaurs with feathered coverings, dramatically changing their appearance from earlier reconstructions. Modern understanding recognizes that dinosaurs were not evolutionary failures but highly successful animals that dominated terrestrial ecosystems for over 160 million years. The dinosaurs that lived just before the extinction represent the culmination of this long evolutionary history, showcasing remarkable adaptations and specializations. Though non-avian dinosaurs disappeared, their avian descendants continue to thrive, with approximately 10,000 species of birds representing the living legacy of dinosaur evolution.

Conclusion

The final chapter of non-avian dinosaur existence represents one of the most fascinating periods in Earth’s biological history. The nine dinosaurs highlighted here—from the towering Alamosaurus to the feathered Dakotaraptor—showcase the remarkable diversity that existed right up until the asteroid impact changed Earth’s trajectory forever. These creatures had evolved highly specialized adaptations over millions of years, creating complex ecosystems that vanished almost overnight in geological terms. Yet their story isn’t simply one of extinction, but also evolutionary success and resilience. The continued study of these final dinosaurs provides valuable insights into how ecosystems respond to catastrophic events and the evolutionary processes that shaped our planet’s history. And perhaps most importantly, their legacy lives on in the birds we see today—the surviving dinosaurs that weathered the storm when their larger relatives could not.