While most of us imagine dinosaurs roaming ancient landscapes under the blazing sun, paleontological evidence increasingly suggests that some dinosaurs may have been active primarily at night. Determining the activity patterns of creatures that went extinct 66 million years ago presents significant challenges, but scientists have developed ingenious methods to investigate this aspect of dinosaur behavior. By examining eye structures in fossils, comparing them with modern nocturnal animals, and analyzing environmental adaptations, researchers have identified several dinosaur species that likely preferred the darkness. These night-dwelling dinosaurs challenge our traditional view of prehistoric life and provide fascinating insights into the diverse ecological niches these remarkable animals occupied during their 165-million-year reign on Earth.

How Scientists Determine Nocturnal Behavior in Extinct Species

Determining whether a dinosaur was nocturnal requires sophisticated scientific detective work. One of the most valuable clues comes from the scleral ring—a ring of bones that surrounds the eye in many vertebrates, including birds and reptiles. In nocturnal animals, these rings tend to be larger relative to eye socket size, allowing more light to enter the eye. Paleontologists also examine the relative size of the olfactory bulbs, as nocturnal animals often rely more heavily on smell than sight. Environmental context provides additional evidence—dinosaurs living in extremely hot environments might have evolved nocturnal habits to avoid daytime heat. Comparisons with modern descendants (birds) and relatives (reptiles) further help scientists establish behavioral patterns that might indicate nighttime activity. These multiple lines of evidence, when converging, create compelling cases for nocturnal behavior in certain dinosaur species.

Troodon: The Night Hunter with Advanced Intelligence

Troodon formosus stands out as one of the strongest candidates for nocturnal behavior among dinosaurs. This small theropod, which lived during the Late Cretaceous period approximately 76-74 million years ago, possessed large eye sockets and expanded optic lobes in its brain, suggesting enhanced visual capabilities particularly suited for low-light conditions. Standing about 3 feet tall and weighing roughly 110 pounds, Troodon had one of the highest brain-to-body mass ratios of any dinosaur, indicating remarkable intelligence that would have served it well during nighttime hunting expeditions. Its forward-facing eyes provided excellent depth perception, while its serrated teeth were perfect for slicing through the flesh of small prey that might have been more vulnerable after dark. Paleontologists believe Troodon’s relatively light build and apparent sensory adaptations made it ideally suited for stalking prey under the cover of darkness.

Velociraptor: Nocturnal Ambush Predator

The infamous Velociraptor, immortalized in popular culture through films like Jurassic Park, may have been a creature of the night. Standing approximately 1.6 feet tall at the hip and measuring around 6.8 feet in length, these mid-sized dromaeosaurids possessed relatively large orbits (eye sockets) that could have accommodated eyes adapted for nocturnal vision. Their narrow snouts housed an impressive olfactory system, suggesting they relied heavily on their sense of smell—a characteristic common in nocturnal hunters. Velociraptors lived in the arid environments of the Late Cretaceous in what is now Mongolia and China, where daytime temperatures could soar, making nighttime hunting a potentially advantageous adaptation. Their sickle-shaped claws and lightweight bodies would have made them efficient ambush predators, possibly using the cover of darkness to surprise sleeping prey. This nocturnal hypothesis helps explain how these relatively small predators could have thrived alongside larger carnivorous dinosaurs that may have dominated daytime hunting grounds.

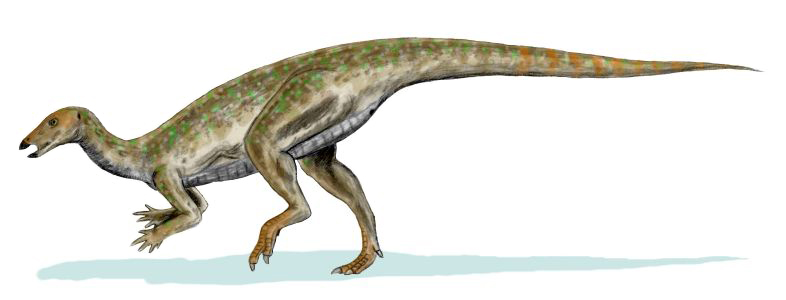

Alvarezsaurus: The Tiny Night Forager

Alvarezsaurus was a peculiar, small theropod dinosaur that lived during the Late Cretaceous period in what is now Argentina. Measuring just 2 meters in length and weighing approximately 20 kilograms, this diminutive dinosaur possessed several characteristics that suggest possible nocturnal behavior. Its skull featured relatively large orbit cavities that could accommodate eyes adapted for gathering light in low-visibility conditions. Alvarezsaurus belonged to a family of dinosaurs with unusual forelimbs featuring a single, enlarged digit that was likely used for breaking into insect nests—particularly termite mounds. Paleontologists speculate that this specialized feeding behavior might have been advantageous at night when termites and other insects might be more exposed or when larger predators were less active. The relatively small size of Alvarezsaurus would have made it vulnerable to larger predators, providing further evolutionary pressure to adopt a nighttime lifestyle that minimized competitive interactions with larger daytime hunters.

Shuvuuia: Desert-Dwelling Night Specialist

Shuvuuia, whose name means “bird” in Mongolian, presents one of the strongest cases for nocturnal behavior among dinosaurs. This chicken-sized alvarezsaurid, which lived in the Late Cretaceous deserts of Mongolia approximately 75-81 million years ago, possessed truly extraordinary adaptations for night vision. A groundbreaking 2021 study published in Science revealed that Shuvuuia had proportionally larger eyes than any other dinosaur and larger even than most modern birds. These eyes contained exceptionally wide pupils and a vast number of rod cells—specialized photoreceptors for low-light vision. Additionally, Shuvuuia’s cochlea structure indicates it had acute hearing, another sense often enhanced in nocturnal animals. Its slender build, with powerful hind limbs and a lightweight skull, suggests it could move swiftly through the desert night, possibly hunting insects and small vertebrates. The extreme desert environment where Shuvuuia lived would have been scorching during the day, making nighttime activity a logical adaptation for this specialized dinosaur.

Megapnosaurus: The Early Nocturnal Theropod

Megapnosaurus (formerly known as Syntarsus) was a slender, primitive theropod dinosaur that lived during the Early Jurassic period, approximately 200-183 million years ago. Standing about 3 feet tall and measuring roughly 10 feet in length, this early carnivore displayed several features consistent with nocturnal behavior. Its skull contained relatively large orbit cavities that could have housed eyes specialized for gathering available light during nighttime hours. Living in what is now Zimbabwe and parts of the southwestern United States, Megapnosaurus inhabited environments that experienced significant temperature fluctuations, potentially making nighttime activity more energetically efficient. As one of the earlier theropods to potentially show nocturnal adaptations, Megapnosaurus may represent an important evolutionary step in the development of nighttime hunting strategies. Its lightweight frame and long, grasping hands would have made it an effective hunter of small prey that themselves might have been active during twilight or nighttime hours, establishing a predator-prey relationship pattern that would continue throughout dinosaur evolution.

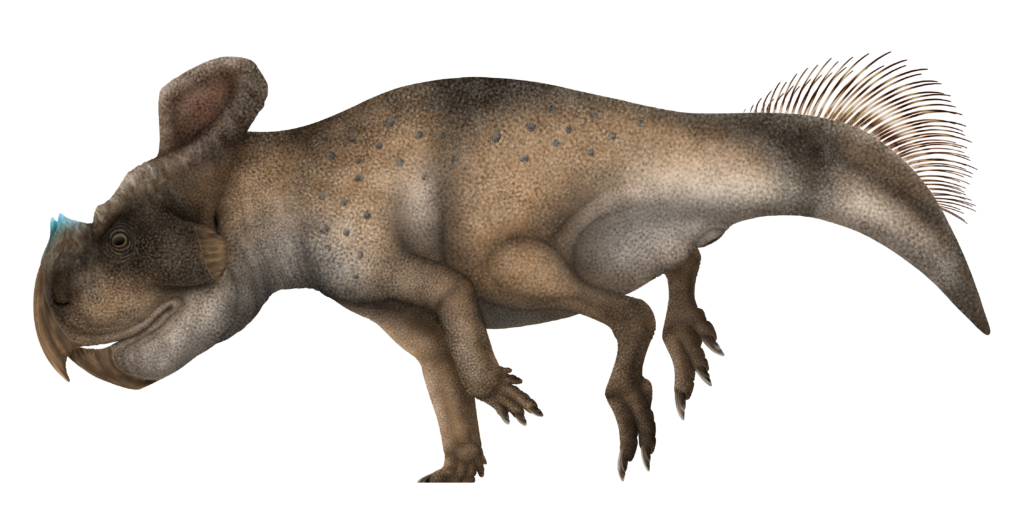

Nocturnality in Ornithischian Dinosaurs: Protoceratops

While nocturnal behavior is often associated with predatory theropods, evidence suggests some ornithischian (bird-hipped) dinosaurs may also have been active after dark. Protoceratops, a sheep-sized ceratopsian from the Late Cretaceous of Mongolia, has been studied for possible nocturnal adaptations. Analysis of its scleral rings—the bones that surrounded and supported the eye—indicates it had eyes capable of functioning in low-light conditions. Standing approximately 2 feet tall at the shoulder and measuring around 6 feet long, Protoceratops inhabited the harsh Mongolian desert where extreme daytime temperatures could have made nighttime foraging advantageous. Its distinctive parrot-like beak was designed for processing tough plant material, which it could have consumed during cooler evening hours when predation risk from larger theropods might have been reduced. The large frills that adorned its skull, while serving display purposes, might have also housed enhanced sensory organs that facilitated navigation in darkness. This evidence challenges the assumption that plant-eating dinosaurs were exclusively diurnal and suggests more complex activity patterns across different dinosaur lineages.

Microraptor: The Four-Winged Nocturnal Glider

The microraptor represents one of the most fascinating candidates for nocturnal behavior among feathered dinosaurs. This crow-sized dromaeosaurid lived during the Early Cretaceous period approximately 120 million years ago in what is now China. Most remarkably, the Microraptor possessed four wings—having feathered limbs on both its arms and legs—that it used for gliding between trees in dense forests. Analysis of exceptionally well-preserved specimens shows evidence of enlarged eye sockets and possible adaptations for low-light vision. Modern nocturnal gliding animals like flying squirrels provide an ecological analog, suggesting that the Microraptor might have utilized a similar nighttime niche. The dense forest canopy where the Microraptor lived created a world of perpetual twilight even during daylight hours, potentially priming this dinosaur for fully nocturnal adaptations. Its small size (about 2.5 feet in length) and vulnerable position in the food chain would have made nighttime activity safer, allowing it to avoid larger predators that hunted during daylight hours. The combination of gliding ability and potential night vision would have made the Microraptor an effective hunter of insects, small vertebrates, and possibly even fish that were active after dark.

Sinosauropteryx: The Fuzzy Night-Time Hunter

Sinosauropteryx holds the distinction of being the first dinosaur found with definitive evidence of feather-like structures, and evidence suggests it may have been adapted for nocturnal hunting. This turkey-sized compsognathid lived during the Early Cretaceous period approximately 124 million years ago in what is now northeastern China. Measuring about 3.5 feet in length and weighing roughly 2-3 pounds, Sinosauropteryx possessed relatively large eyes compared to its skull size, suggesting enhanced visual capability potentially suited for low-light conditions. Remarkably well-preserved specimens show evidence of a striped tail pattern that would have provided effective camouflage in dappled moonlight filtering through a forest canopy. Analysis of stomach contents from fossilized specimens reveals small mammals and lizards that might themselves have been primarily nocturnal, indicating Sinosauropteryx hunted prey that was active at night. The primitive insulating feathers covering its body would have helped maintain body temperature during cooler nighttime hours, further supporting the possibility that this small predator was adapted for nocturnal activity patterns.

Oviraptor: Protecting Nests Under Cover of Darkness

Oviraptor, whose name ironically means “egg thief” (based on an initial misunderstanding of its behavior), presents an interesting case for potential nocturnal nesting behavior. This beaked, bird-like theropod lived during the Late Cretaceous period around 75-71 million years ago in what is now Mongolia and China. Standing approximately 3 feet tall and measuring 6-8 feet in length, the Oviraptor possessed relatively large eye sockets that could have housed vision systems adapted for low-light conditions. Several Oviraptor specimens have been found fossilized while sitting on nests, suggesting dedicated parental care. Paleontologists hypothesize that these dinosaurs might have engaged in nighttime incubation behavior to protect their eggs from the extreme daytime heat of their desert habitat and to shield them from daytime predators. This protective strategy mirrors behaviors seen in some modern birds that nest in harsh environments. The Oviraptor’s unusual skull, with its distinctive crest, may have housed enhanced sensory capabilities that facilitated navigation and nest protection during darker hours, allowing these devoted parents to guard their developing offspring through the vulnerable night hours.

Evolutionary Advantages of Nocturnal Behavior in Dinosaurs

Nocturnal behavior would have provided numerous evolutionary advantages for the dinosaur species that adopted this lifestyle. Perhaps most significantly, nighttime activity allowed smaller predatory dinosaurs to avoid direct competition with larger carnivores that dominated daytime hunting grounds, effectively creating temporal niche partitioning. For herbivorous dinosaurs, foraging at night reduced predation risk and allowed them to feed during cooler hours in hot environments, improving thermoregulatory efficiency. Nocturnal activity patterns also opened up new hunting opportunities, as many small mammals, insects, and other potential prey items were themselves nocturnal. From an environmental perspective, regions with extreme daytime temperatures would have strongly selected for night-active behavior, particularly in desert environments where many potentially nocturnal dinosaur fossils have been discovered. The diversity of dinosaurs showing possible nocturnal adaptations—from tiny insectivores to dedicated nest-guarders—demonstrates how this behavioral adaptation spread across multiple evolutionary lineages, suggesting it was a successful strategy that emerged repeatedly throughout the Mesozoic Era.

Challenges in Identifying Nocturnal Dinosaurs

Despite growing evidence for nocturnal behavior in certain dinosaurs, paleontologists face significant challenges when attempting to definitively classify extinct species’ activity patterns. The fossil record, while impressive, preserves only a fraction of the anatomical information needed to make absolute determinations about behavioral adaptations. Soft tissues like retinas, which in modern animals clearly indicate nocturnal specialization, rarely fossilize. Even well-preserved scleral rings can be ambiguous, as some modern animals with these structures exhibit cathemeral behavior (activity during both day and night) rather than strict nocturnality. The evolutionary distance between dinosaurs and their closest living relatives—birds and crocodilians—further complicates direct comparisons of sensory adaptations. Environmental contexts can change dramatically over geological time, potentially leading to misinterpretations of behavioral adaptations. Additionally, many dinosaur species might have been crepuscular (active primarily during dawn and dusk) rather than fully nocturnal, creating a spectrum of activity patterns that defy simple classification. These challenges remind us that while evidence increasingly supports nocturnal behavior in certain dinosaurs, we must approach these conclusions with appropriate scientific caution.

Modern Descendants: Nocturnal Birds and Their Dinosaur Connection

Birds, as the direct descendants of theropod dinosaurs, provide valuable insights into the potential nocturnal capabilities of their prehistoric ancestors. Numerous modern bird species exhibit fully nocturnal behavior, with owls representing the most specialized night-active avian group. These birds possess remarkable adaptations, including extremely large, forward-facing eyes, specialized retinal structures rich in rod cells, and enhanced hearing capabilities—all adaptations that leave traces in skeletal structures similar to those examined in potentially nocturnal dinosaurs. The kiwi of New Zealand, another fully nocturnal bird, relies heavily on its sense of smell and touch, demonstrating alternative sensory specializations for nighttime activity. Nightjars, potoos, and frogmouths represent additional nocturnal avian lineages that evolved their specialized lifestyles independently, suggesting that the underlying genetic framework for developing nocturnal adaptations was present in the dinosaur ancestors of modern birds. This widespread occurrence of nocturnality across diverse bird groups strengthens the case that some dinosaur lineages likely possessed both the genetic predisposition and evolutionary opportunity to develop nighttime activity patterns. The success of nocturnal birds in the modern world perhaps reflects behavioral and sensory adaptations first pioneered by their dinosaur ancestors millions of years ago.

Future Research Directions in Dinosaur Chronobiology

The study of dinosaur activity patterns represents an exciting frontier in paleontological research with numerous promising avenues for future investigation. Advanced imaging technologies like synchrotron microtomography now allow scientists to examine the internal structures of fossilized eye sockets and brain cases with unprecedented detail, potentially revealing adaptations specifically associated with nocturnal vision. Comparative studies of eye structure across living reptiles and birds with known activity patterns will help refine our understanding of the relationship between skeletal features and nocturnal behavior. Chemical analysis of fossilized teeth and bones may eventually provide insights into circadian rhythms through growth patterns and stress markers. Environmental reconstruction techniques are becoming increasingly sophisticated, allowing more precise determinations of the temperature regimes and ecological pressures that might have favored nocturnal adaptations. Genomic studies of modern birds are identifying specific genes associated with nocturnal adaptations, which may eventually be traced back to their dinosaur origins through molecular clock analyses. As these research approaches continue to advance, our understanding of when dinosaurs roamed—whether under the blazing sun or the silvery moon—will become increasingly nuanced, painting a more complete picture of how these remarkable animals lived.