When you think about dinosaurs, your mind probably jumps straight to Tyrannosaurus rex or maybe Triceratops. Those are the celebrities, the headliners, the ones that get all the attention in museums and movies. They deserve their fame, sure, yet there’s something deeply unfair about how many fascinating creatures get left in the shadows.

Utah is home to over a hundred dinosaur species, and honestly, most people couldn’t name more than a handful. Think about it this way: ancient Utah was like a bustling city, and while everyone remembers the mayor, they forget about all the essential workers keeping things running. The herbivores munching vegetation, the small predators controlling pest populations, the armored tanks protecting breeding grounds. These overlooked dinosaurs weren’t just background noise. They were the backbone of an ecosystem that thrived for millions of years across what we now call the Beehive State.

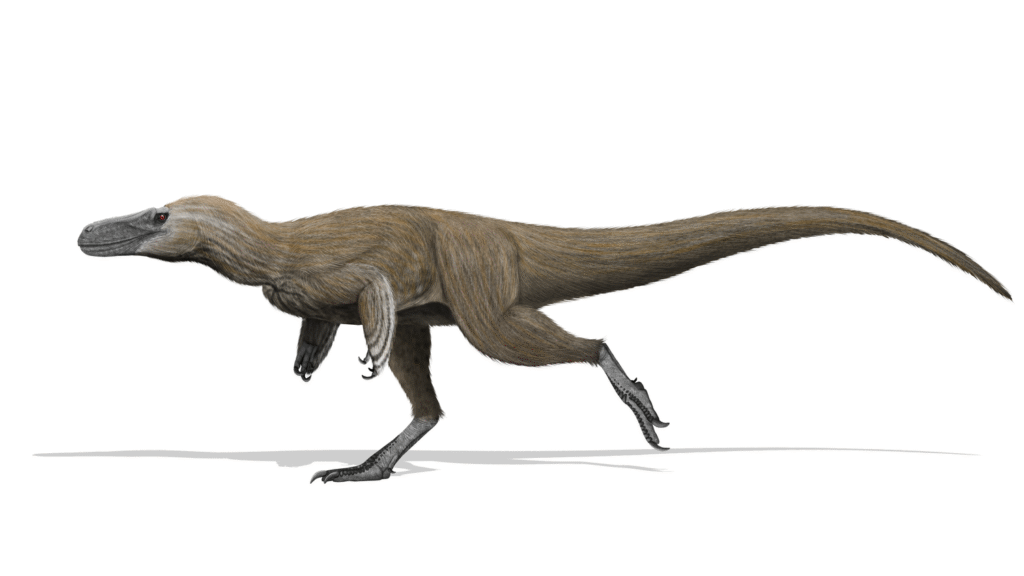

Nedcolbertia: The Swift Opportunist

Nedcolbertia justinhoffmani was a small coelurosaur that lived during the Early Cretaceous period, and let me tell you, this little predator punched way above its weight class. This meat-eating dinosaur, along with the giant raptor Utahraptor and a large carnosaurid, represented the theropod diversity of the Yellow Cat Member fauna, living approximately 125 to 120 million years ago. Picture something about the size of a large dog, built for speed rather than power.

Nedcolbertia shared its environment with the ankylosaur Gastonia, large ornithopods, sauropods, therizinosaurs, the troodontid Geminiraptor, and other raptors. In an ecosystem dominated by much larger predators, Nedcolbertia likely played a crucial scavenger role. Think of it as nature’s cleanup crew, preventing disease spread and recycling nutrients back into the food chain. Its relatively straight manual claws and lightweight build suggest it was an agile hunter of small prey, filling an ecological niche that larger predators simply couldn’t access.

Cedarosaurus: The Gentle Giant Browser

Here’s where things get interesting with the plant eaters. Cedarosaurus weiskopfae was a brachiosaurid sauropod found in the Yellow Cat Member, one of those long-necked dinosaurs that looks like it shouldn’t be able to exist. This sauropod may be considered a relic, with its closest relatives in the Morrison Formation, suggesting it was a holdover from earlier times.

These weren’t just big dumb eating machines, despite what popular culture might suggest. Cedarosaurus lived alongside creatures like Utahraptor, Gastonia, and various iguanodonts in the Cedar Mountain Formation. As a high browser, this dinosaur would have reached vegetation that smaller herbivores couldn’t access, preventing any single plant species from dominating the canopy. By constantly moving and feeding, sauropods like Cedarosaurus shaped the entire landscape, creating clearings and distributing seeds across vast distances. They were essentially walking ecosystem engineers.

Gastonia: The Armored Defender

Gastonia burgei was a polacanthine ankylosaur that looked like someone designed a tank and then decided it needed more spikes. This dinosaur lived in a wooded environment with a dry climate and short wet seasons, and was a very abundant animal, probably due to its armor protecting it from predators. Honestly, looking at reconstructions of Gastonia, you have to wonder what predator would even bother trying.

Living in a wooded environment with dry climate and short wet seasons, Gastonia was very abundant, probably due to its armor protecting it from predators, and it may have even lived in social groups given its prevalence. Here’s something most people don’t consider: armored herbivores weren’t just prey animals trying to survive. They were landscape modifiers. By feeding on low-lying vegetation and using their heavily armored bodies to push through dense undergrowth, they created pathways that other animals used. Their social behavior also suggests they might have defended territories, which would have influenced where other species could live and feed.

Martharaptor: The Mysterious Sloth Mimic

Martharaptor was discovered in Cretaceous rocks outside Moab and named in 2012, and if this dinosaur was anything like its close relatives, it would have looked something like a dinosaur doing an impression of a giant sloth. Let’s be real, that’s one of the strangest mental images paleontology gives us. Martharaptor greenriverensis belonged to Therizinosauroidea and added to the known dinosaurian fauna of the Yellow Cat Member of the Cedar Mountain Formation.

These omnivorous and herbivorous dinosaurs descended from a carnivorous ancestor and stand out in having long necks, large hand claws and a heavier frame. The ecological role of therizinosaurs like Martharaptor is debated, yet their specialized claws suggest they were expert foragers, possibly stripping bark or pulling down branches. In an ecosystem packed with different herbivore body types, Martharaptor occupied a niche between ground feeders and high browsers, accessing mid-level vegetation that might otherwise have gone unused.

Moros Intrepidus: The Harbinger of Change

Moros intrepidus was a small tyrannosauroid theropod dinosaur that lived during the Late Cretaceous period, representing one of the earliest known diagnostic tyrannosauroid material from North America. This small-bodied, cursorial tyrannosauroid had an estimated leg length of 1.2 meters and a body mass of 78 kilograms. Picture something roughly the size of a large human, built like a greyhound, prowling through the undergrowth.

Moros intrepidus was a small carnivore that probably would have had to worry about other carnivores, yet tyrannosauroids somehow evolved from marginal scavengers to top predators in just 30 million years. The ecological significance here is profound. Small predators like Moros would have controlled populations of even smaller animals, preventing any one species from overwhelming the ecosystem. They were also likely opportunistic feeders, switching between hunting and scavenging depending on what was available. That flexibility is what kept ecosystems resilient during times of environmental stress.

Iani Smithi: The Transitional Survivor

Iani smithi is a dinosaur from the 99-million-year-old rock of Utah, named after the Roman god Ianus who oversaw transitions, and is known from a partial skeleton that includes much of the skull as well as portions of the spine and limbs. In life, this beaked, plant-munching creature was about 12 feet from the tip of its snout to the end of its tail. It’s hard to say for sure, but there’s something poignant about a dinosaur literally named after transitions.

Iani joined the hadrosaur relative Eolambia, an unnamed species of thescelosaur, armored dinosaurs, and horned dinosaurs, representing at least five groups of herbivorous dinosaurs present as classic dinosaur communities of the Late Cretaceous were evolving. Rhabdodontomorphs like Iani were somewhat like the antelope or deer of their time, filling the medium-sized herbivore niche in their communities. These medium-sized herbivores were critical for nutrient cycling, converting plant matter into forms accessible to carnivores and enriching the soil with their waste.

Venenosaurus: The Titanosaur Pioneer

Venenosaurus dicrocei was a titanosaurimorph sauropod found in the Poison Strip Sandstone, representing a different lineage of long-necked herbivores than Cedarosaurus. The Poison Strip Sandstone indicated a complex of beaches and low-sinuosity and meandering river systems, with petrified logs and cycads common in these beds. This tells us something important about habitat diversity.

Sauropods such as Venenosaurus and Cedarosaurus were found alongside various iguanodonts, the hadrosauroid Eolambia, and the ankylosaur Gastonia. Having multiple sauropod species coexisting suggests they weren’t competing for the same resources. Venenosaurus likely had different feeding preferences or behaviors than Cedarosaurus, allowing both to thrive. This niche partitioning is what made ancient Utah’s ecosystems so remarkably productive. No resource went to waste when you had specialists evolved to exploit every available food source.

Stokesosaurus: The Early Tyrant

In 1974 James Madsen Jr. described a hip bone from eastern Utah’s Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry as Stokesosaurus in honor of colleague William Stokes, and we now know that Stokesosaurus was an early tyrannosaur, about the size of a Labrador Retriever with a svelte build very different from that of its later cousin. Think of it as the prototype for what would eventually become the most fearsome predators on land.

This small early tyrannosaur lived during the Late Jurassic, predating the more famous Cedar Mountain fauna by millions of years. Its ecological role would have been similar to Nedcolbertia in later ecosystems, controlling populations of small to medium-sized prey animals. What makes Stokesosaurus particularly fascinating is that it shows tyrannosaurs weren’t always apex predators. They started small and opportunistic, filling whatever niches were available, adapting and evolving as circumstances changed over tens of millions of years.

Dystrophaeus: Utah’s First Discovery

Dystrophaeus was a long-necked plant eater that lived about 154 million years ago and is the oldest known member of a group of dinosaurs called sauropods. Named all the way back in 1877, it was Utah’s first unique dinosaur. There’s something deeply appropriate about starting this list with the newest discoveries and ending with the very first.

Dystrophaeus viaemalae was a sauropod dinosaur discovered on the 1859 Macomb Expedition to southeastern Utah, making it not just Utah’s first dinosaur but one of the earliest dinosaur discoveries in North America. Despite being known from limited material, Dystrophaeus represents the foundation of Utah’s incredible paleontological legacy. It reminds us that these ancient ecosystems extended far back in time, with lineages rising, adapting, and eventually giving way to new forms across incomprehensible spans of years.

Conclusion: The Hidden Architecture of Ancient Life

Paleontologists have recognized about 30 distinct species that are only found in southern Utah’s Grand Staircase-Escalante area, of which about 15 are dinosaurs. That’s just one region, and there are dozens more waiting to be explored. Every overlooked dinosaur we’ve discussed played an irreplaceable role in keeping ancient Utah’s ecosystems functioning.

The armored herbivores created pathways. The small predators controlled pest populations. The various sauropods prevented any single plant species from taking over. The medium-sized herbivores recycled nutrients. Together, they formed an intricate web of interactions that sustained life for millions of years. We tend to focus on the spectacular, the enormous, the apex predators. Yet ecosystems don’t run on spectacle alone. They run on diversity, on specialization, on countless species each doing their small part.

So what would you have guessed about these forgotten giants before reading this? Did any of them surprise you with their ecological importance?