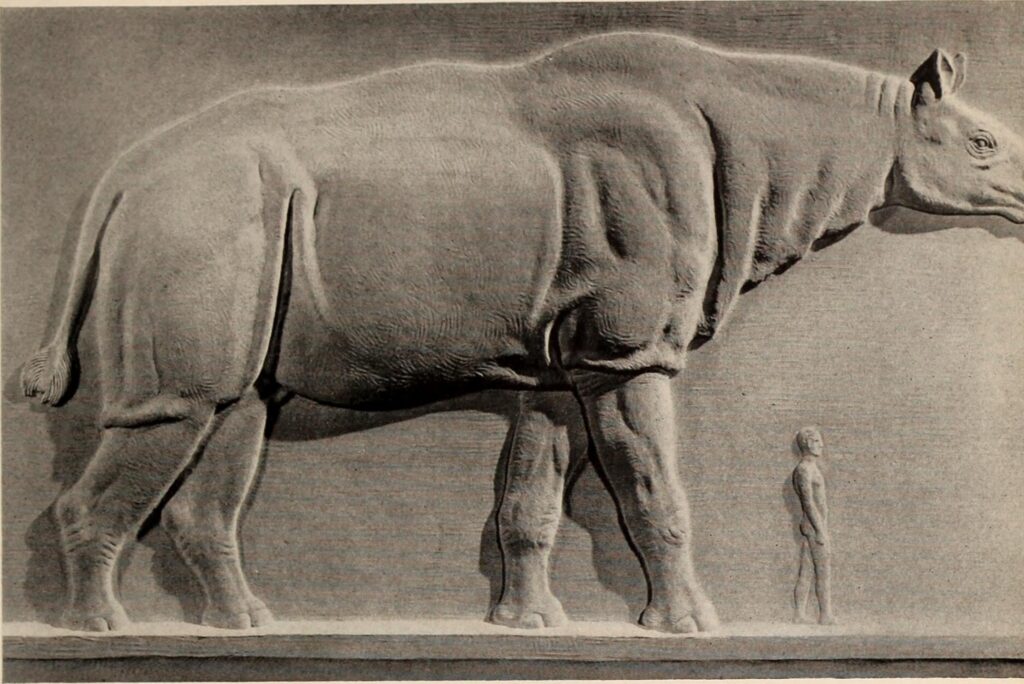

Imagine a creature so massive that its shoulders reached heights of 15 feet, with a body stretching more than 25 feet long and weighing up to 20 tons. This wasn’t a dinosaur, but rather a mammal that wandered the landscapes of Asia millions of years after the dinosaurs disappeared. Paraceratherium, formerly known as Indricotherium or Baluchitherium, holds the distinction of being the largest land mammal ever discovered. During the Oligocene epoch, roughly 34 to 23 million years ago, these colossal beasts dominated the Asian continent, leaving an indelible mark on evolutionary history. Their story is one of adaptation, survival, and ultimately extinction, offering fascinating insights into Earth’s prehistoric past when giants walked among the emerging world of mammals.

The Discovery: Unearthing a Giant

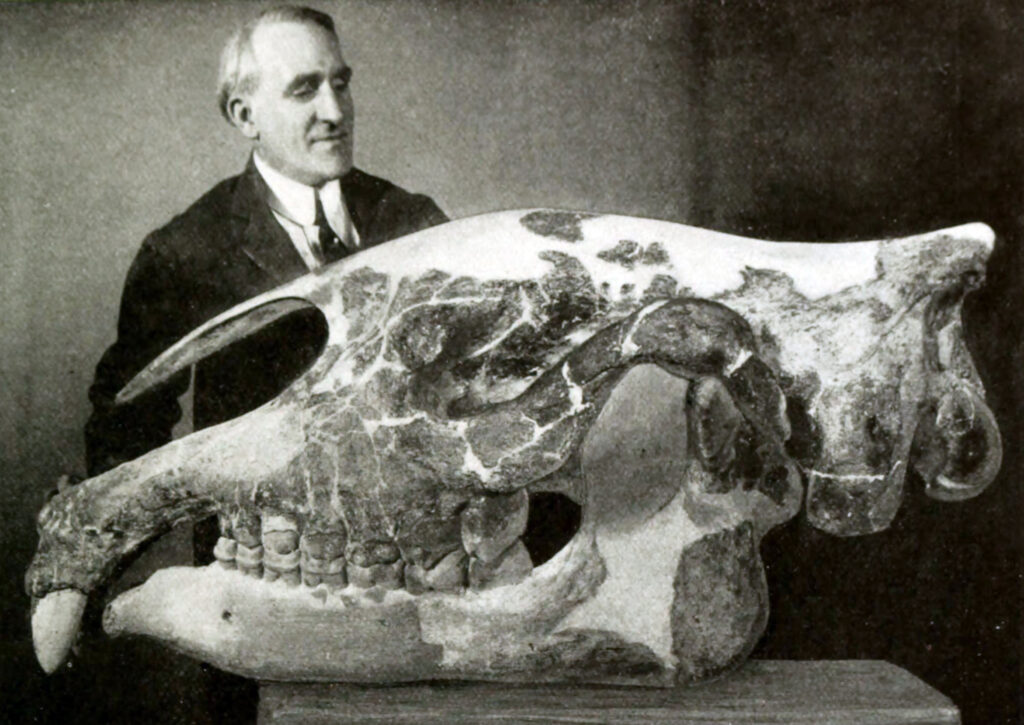

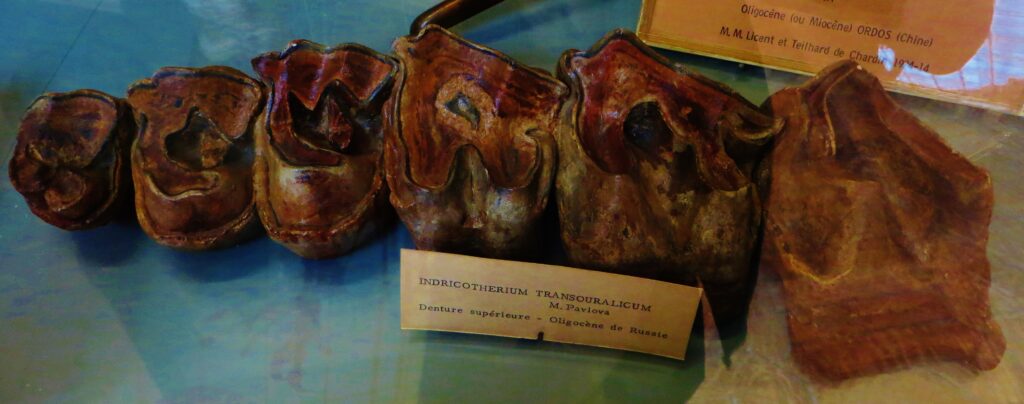

The scientific journey to understand Paraceratherium began in the early 20th century when paleontologists working in Asia made remarkable fossil discoveries. In 1910, Russian paleontologist Alexei Borissiak discovered the first remains in Kazakhstan, naming his find Indricotherium. Almost simultaneously, British paleontologist Sir Clive Forster-Cooper found similar fossils in Baluchistan (now part of Pakistan), naming his specimen Baluchitherium. For decades, scientists debated whether these represented different genera until further research in the 1980s determined they were the same animal, with Paraceratherium becoming the accepted name. The fragmentary nature of the fossils—primarily consisting of jaws, teeth, and limb bones—made reconstruction challenging, requiring decades of additional discoveries and scientific analysis to piece together an accurate picture of this prehistoric giant.

Evolutionary Origins: The Rise of the Hornless Rhinos

Paraceratherium belonged to the family Hyracodontidae, an extinct group of hornless rhinoceroses that diverged from the lineage leading to modern rhinos. Their evolutionary journey began in the Eocene epoch, around 56 to 34 million years ago, when early perissodactyls (odd-toed ungulates) were diversifying across the Northern Hemisphere. Unlike their modern relatives, these early rhinoceroses lacked horns and evolved to fill ecological niches more similar to those occupied by today’s horses or tapirs. The genus evolved during a period of global cooling when forests began giving way to more open woodlands and grasslands across Asia. Paraceratherium’s enormous size represented an evolutionary response to these changing landscapes, allowing it to browse vegetation at heights unreachable by competitors and providing protection against the predators of the time.

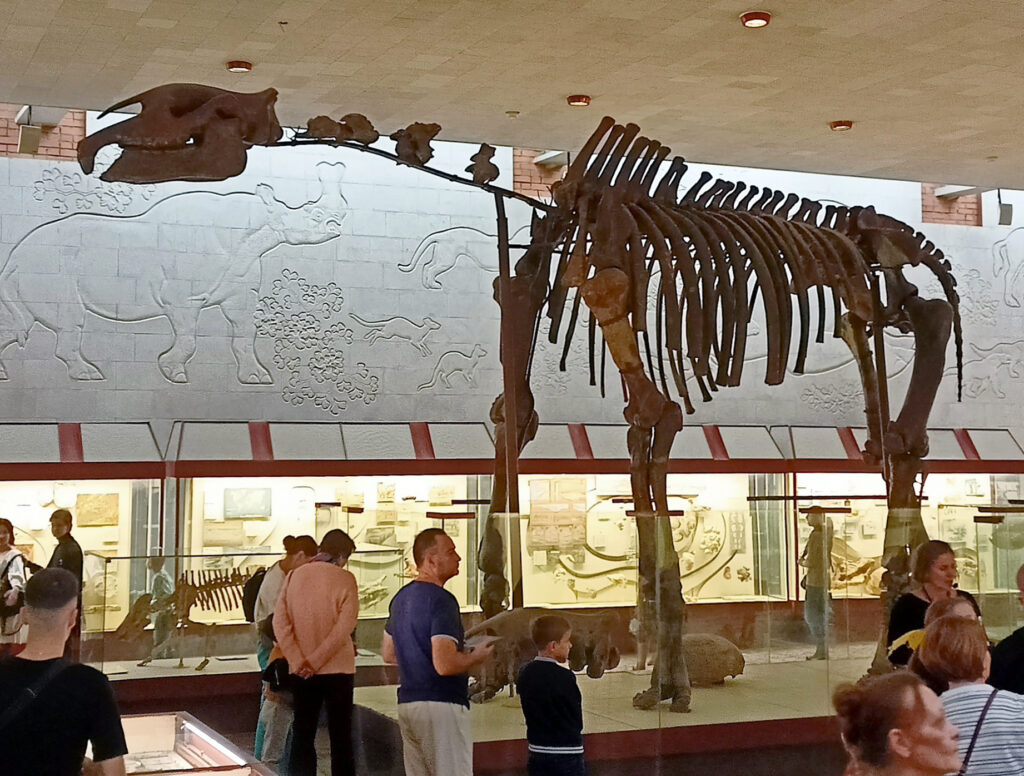

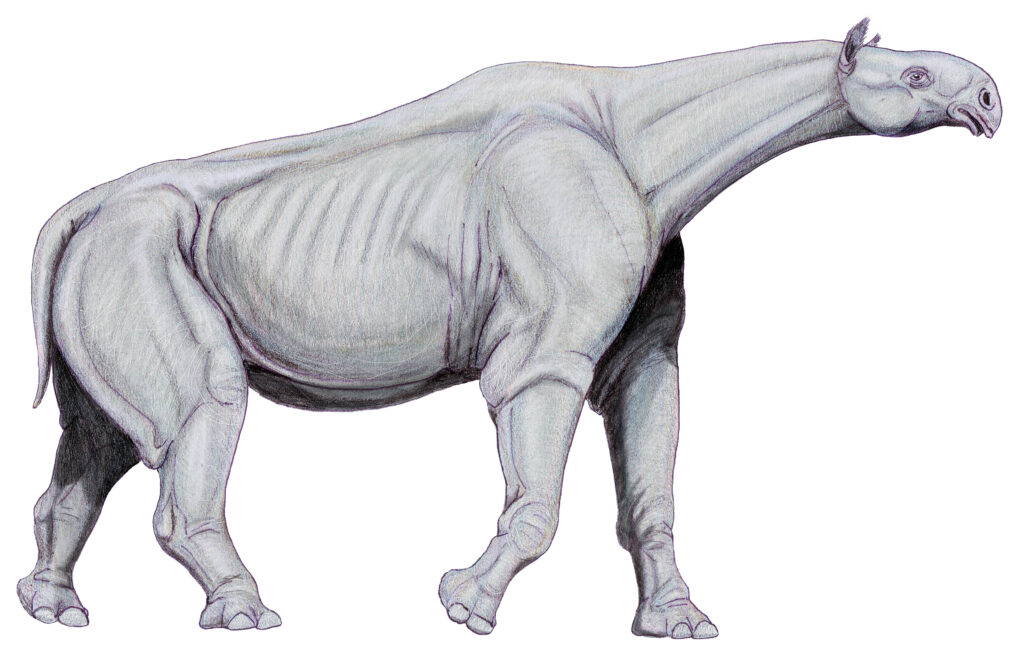

Anatomy of a Giant: Building the Largest Land Mammal

Paraceratherium’s anatomy was a marvel of evolutionary engineering, built to support its tremendous weight while maintaining mobility. Its legs were columnar and elephant-like, with specialized joints and bone structures that could bear the animal’s massive weight. The neck was remarkably elongated, allowing the creature to reach high into trees for foliage, similar to modern giraffes but on a more massive scale. Its skull measured over four feet long, housing a relatively small brain compared to its body size, which is typical for large herbivores that don’t require complex problem-solving abilities. Most notably, Paraceratherium had a distinctive nasal region that suggests it possessed a prehensile upper lip or short trunk, similar to modern tapirs, which would have been crucial for gathering and manipulating foliage. Unlike modern rhinoceroses, it lacked horns entirely, relying instead on its sheer size for protection against predators.

Diet and Feeding Habits: The Voracious Appetite of a Colossus

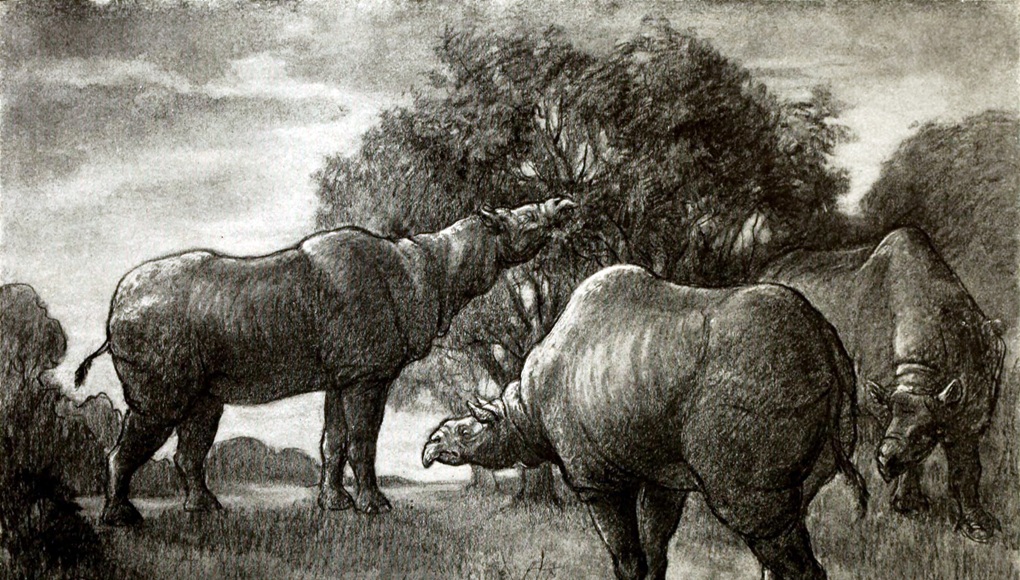

Maintaining a body of such enormous proportions required Paraceratherium to consume tremendous amounts of vegetation daily, likely between 750-1,000 pounds of plant matter. Paleontological evidence, particularly dental and jaw structures, indicates these giants were browsers rather than grazers, feeding primarily on leaves, branches, and other soft vegetation from trees and tall shrubs. Their high-crowned teeth were specialized for processing tough, woody plant materials, with powerful jaw muscles that could crush branches and strip bark. The creature’s towering height allowed it to access food sources unavailable to smaller competitors, reaching vegetation up to 23 feet above ground level. This feeding strategy likely involved a form of “high browsing” where Paraceratherium could exploit ecological niches inaccessible to other herbivores of the time, effectively reducing competition for resources and enabling them to thrive across vast territories of prehistoric Asia.

Habitat and Range: The Asian Dominion

Paraceratherium fossils have been discovered across a vast swath of Asia, from the former Soviet republics of Kazakhstan and Mongolia through China, Pakistan, and as far south as the Indian subcontinent. During the Oligocene, these regions looked dramatically different from what they do today, comprising a mosaic of open woodlands, savanna-like grasslands, and gallery forests following river systems. The climate was generally more arid than the preceding Eocene epoch, with pronounced seasonal variations. Fossil evidence suggests these giants preferred semi-open woodland environments where they could browse on trees while still having room to maneuver their massive bodies. Notably, their range coincided with the early formation of the Himalayan mountain range, as the Indian subcontinent continued its collision with Asia. This changing landscape created diverse habitats with varying elevations and vegetation types, allowing Paraceratherium populations to adapt to different ecological niches across their extensive range.

Social Structure: Lone Wanderers or Herd Animals?

The social behavior of Paraceratherium remains one of the most intriguing mysteries surrounding these prehistoric giants. While no direct evidence of their social structure exists, paleontologists have developed theories based on comparisons with modern relatives and ecological considerations. Some scientists propose that, like modern rhinos, Paraceratherium may have been largely solitary, with adults coming together only for mating. Others suggest they might have formed small family groups similar to elephants, particularly during breeding seasons or while raising young. Fossil deposits occasionally show multiple individuals preserved in proximity, though this could represent deaths at water sources during drought rather than social grouping. The massive food requirements for each individual would have made large, permanent herds unsustainable, as local vegetation would be quickly depleted. Sexual dimorphism evidence is limited but suggests males may have been somewhat larger than females, potentially indicating competition for mates and a polygynous breeding system.

Reproduction and Growth: Raising Baby Giants

The reproductive biology of Paraceratherium likely represented one of the most extreme examples of mammalian development. Based on comparisons with modern elephants and rhinoceroses, paleobiologists estimate that females would have had extraordinarily long gestation periods, possibly lasting 15-20 months. Calves would have been born at sizes already larger than many adult mammals, perhaps weighing as much as 500-1,000 pounds at birth. The energetic demands of producing such offspring would have meant females could reproduce only every several years. Young Paraceratherium would have experienced extended growth periods, taking perhaps 10-15 years to reach full adult size and sexual maturity. The lengthy development period suggests significant parental investment, with mothers protecting and nursing their calves for extended periods, potentially several years. This slow reproductive rate would have made populations vulnerable to environmental changes, contributing to their eventual extinction when conditions shifted unfavorably.

Predators and Defense: Too Big to Fail?

Adult Paraceratherium, with their towering height and immense mass, would have been virtually immune to predation from most carnivores of their time. The largest predators of the Oligocene epoch, including entelodonts (giant “hell pigs”), hyaenodonts, and early nimravids (false saber-toothed cats), would have posed little threat to a healthy adult. However, young, sick, or elderly individuals would have been vulnerable, particularly to pack-hunting predators that could coordinate attacks. Unlike modern rhinoceroses, Paraceratherium lacked horns for defense, instead relying primarily on their enormous size, powerful limbs, and possibly behaviors like kicking or trampling to deter threats. Their exceptional height would have provided excellent visibility across open landscapes, allowing them to spot approaching dangers from considerable distances. Some paleontologists speculate they may have used their elongated heads as battering rams during confrontations, though this remains conjectural without direct evidence of such behavior preserved in the fossil record.

Environmental Impact: Ecosystem Engineers

As the largest herbivores of their time, Paraceratherium would have exerted tremendous influence on their environments, functioning as ecosystem engineers that physically modified habitats. Their feeding habits likely transformed woodland areas by pruning trees, creating clearings, and maintaining open corridors through forests. Each individual’s daily consumption of hundreds of pounds of vegetation would have significantly impacted plant communities, potentially favoring certain species that could tolerate or quickly recover from browsing. Their massive weight would have compacted soil along regular travel routes, creating natural pathways that other animals might follow. Like modern elephants, they may have uprooted smaller trees and broken branches high above the ground, creating microhabitats for other organisms. Their dung would have distributed plant seeds across vast distances, facilitating plant dispersal and succession. Even in death, their enormous carcasses would have provided critical resources for scavengers and decomposers, creating temporary hotspots of biodiversity wherever these giants fell.

Extinction: The End of the Giants

The twilight of the Paraceratherium era came during the late Oligocene to early Miocene epochs, approximately 23 million years ago, when these magnificent creatures disappeared from the fossil record. Their extinction coincided with significant global and regional environmental changes. Climate shifts brought cooler, drier conditions across much of Asia, transforming woodland habitats into more open grasslands less suitable for browsing giants. Simultaneously, the continued collision of the Indian subcontinent with Asia altered landscapes and weather patterns across the region. Perhaps most significantly, this period saw the emergence of new herbivore competitors, particularly the early proboscideans (elephant ancestors) that migrated from Africa into Asia. These newcomers could exploit similar food resources but had more efficient digestive systems and reproductive strategies. The combination of habitat loss, climate change, and competition proved insurmountable for Paraceratherium, whose specialized adaptations and slow reproductive rate left them unable to adapt quickly enough to the changing world around them.

Cultural Impact: Giants in the Modern Imagination

Despite vanishing millions of years before humans evolved, Paraceratherium has captured the modern imagination since its discovery. These prehistoric giants have featured prominently in popular culture, appearing in documentaries like the BBC’s “Walking with Beasts” series, which brought their story to millions of viewers worldwide. Museum displays featuring Paraceratherium reconstructions have become centerpieces in natural history institutions, drawing crowds fascinated by their incomprehensible scale compared to modern mammals. The creature has inspired countless artistic reconstructions, from scientific illustrations to dramatic paintings depicting these colossal mammals wandering through ancient Asian landscapes. In fiction, they’ve appeared in prehistoric-themed novels and even influenced the design of fantastical creatures in films and video games. Their story provides a compelling educational opportunity, helping to illustrate concepts of evolution, adaptation, and extinction while demonstrating that Earth’s history includes mammals as impressive and awe-inspiring as any dinosaur.

Research Challenges: Piecing Together a Prehistoric Puzzle

Studying Paraceratherium presents paleontologists with unique challenges that continue to complicate our understanding of these prehistoric giants. Complete skeletons remain exceedingly rare, with most specimens consisting of fragmentary remains that require careful interpretation and comparative analysis. The enormous size of the bones creates logistical difficulties during excavation, transportation, and storage, often requiring specialized equipment and facilities. Geographic and political factors have historically limited access to fossil sites across Central Asia, with international tensions and restricted areas impeding comprehensive field research. Dating the fossils precisely has proven challenging due to the nature of the sedimentary deposits where they’re typically found. Additionally, the taxonomy remains contentious, with ongoing debates about whether certain specimens represent different species or merely reflect individual variation, sexual dimorphism, or developmental stages. Despite these obstacles, advanced technologies like CT scanning, 3D modeling, and isotope analysis are gradually revealing new insights about these magnificent creatures, filling gaps in our knowledge about their anatomy, physiology, and behavior.

Modern Relatives: The Rhino Family Legacy

Though Paraceratherium dwarfed any living rhinoceros, they share a common evolutionary heritage as members of the order Perissodactyla (odd-toed ungulates). Modern rhinoceroses represent the surviving branch of a once-diverse lineage that included Paraceratherium’s family, the Hyracodontidae. Today’s five rhinoceros species—the white, black, Indian, Javan, and Sumatran—are mere shadows of their giant cousin’s proportions, with even the largest white rhino reaching only about one-fifteenth the mass of an adult Paraceratherium. Unlike their hornless ancestor, modern rhinos evolved distinctive keratin horns as their primary defensive feature. Comparison between Paraceratherium and contemporary rhinos illustrates evolutionary divergence, with modern species adapting to different ecological niches as browsers or grazers. Tragically, all extant rhinoceros species face severe conservation challenges, with three classified as critically endangered due to habitat loss and poaching. In a sobering parallel, the environmental pressures driving modern rhinos toward extinction—habitat transformation and human exploitation—echo the ecological challenges that contributed to Paraceratherium’s disappearance millions of years earlier.

The Rise and Fall of a Prehistoric Giant

The story of Paraceratherium stands as a testament to the extraordinary diversity of life that has inhabited our planet through deep time. These colossal mammals, reaching sizes that stretched the very limits of what’s physically possible for land animals, ruled the landscapes of Asia for millions of years before disappearing forever. Their existence challenges our perception of what’s possible in mammalian evolution and reminds us that many of history’s most remarkable creatures left no direct descendants. As we continue piecing together their story from fragmentary remains scattered across Asia, Paraceratherium offers valuable insights into the processes of adaptation, specialization, and extinction that have shaped life on Earth. In a world currently facing another mass extinction event, understanding these prehistoric giants may provide crucial perspectives on the vulnerability of even the most seemingly indomitable species to environmental change. The reign of the house-sized rhinoceros has long since ended, but its legacy lives on in the fossil record and in our collective fascination with the prehistoric giants that once called our planet home.