Long before Tyrannosaurus rex and Velociraptor dominated the prehistoric landscape, a different cast of predators roamed the early dinosaur world. The Triassic period (252-201 million years ago) marked the dawn of dinosaur evolution, where early experiments in dinosaur design produced some remarkable predators that would set the stage for the more famous theropods of later eras. Among these pioneers, Herrerasaurus stands as one of the most significant early hunters, but it was far from alone. These lean, agile predators navigated a world vastly different from the dinosaur-dominated ecosystems that would follow, competing with various non-dinosaurian reptiles while establishing the blueprint for dinosaurian success. This article explores Herrerasaurus and its contemporaries, offering a window into the forests and plains of the early Mesozoic Era when dinosaurs were just beginning their evolutionary journey.

The Dawn of Dinosaurs: Setting the Triassic Stage

The Triassic period emerged from the shadow of the greatest mass extinction in Earth’s history, the Permian-Triassic extinction event that wiped out nearly 96% of marine species and 70% of terrestrial vertebrates. This catastrophic reset of Earth’s ecosystems created evolutionary opportunities for surviving groups, including the archosaurs—the group that would eventually give rise to dinosaurs, pterosaurs, and crocodilians. The early Triassic landscape was dominated by synapsids (ancestors of mammals) and various reptilian groups, with true dinosaurs appearing relatively late in the period, around 230-225 million years ago. During this time, the world’s continents were united in the supercontinent Pangaea, creating vast inland areas with seasonal extremes of temperature and precipitation. This challenging environment favored adaptable, efficient predators, setting the stage for the rise of dinosaurs like Herrerasaurus, whose anatomical innovations would prove remarkably successful.

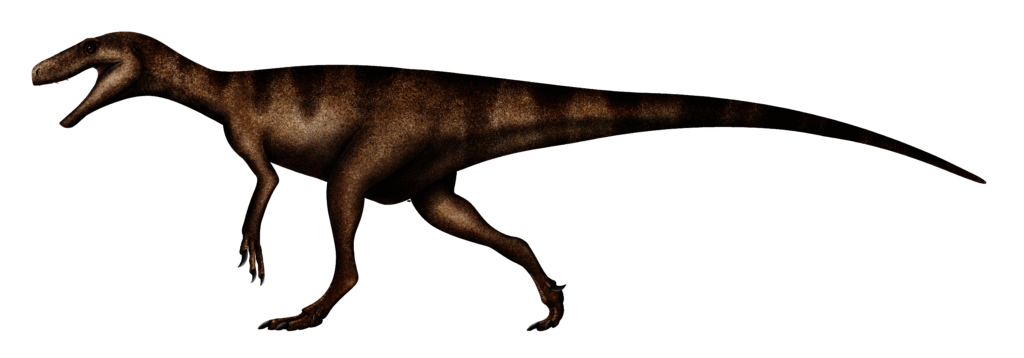

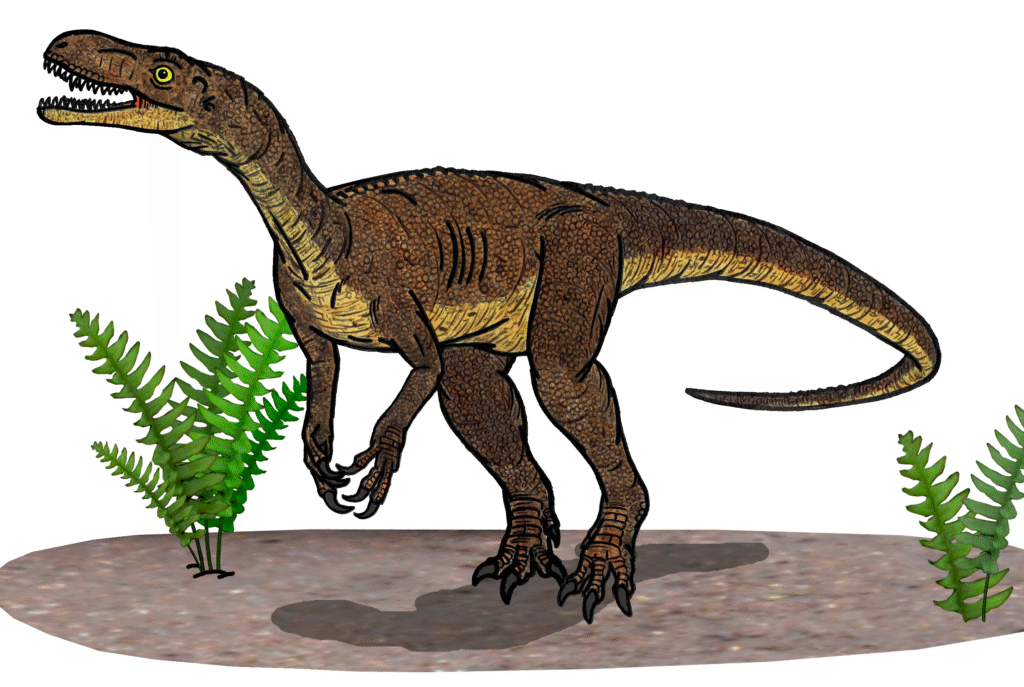

Herrerasaurus: The Pioneering Predator

Discovered in Argentina’s Ischigualasto Formation and dating to approximately 231 million years ago, Herrerasaurus ischigualastensis represents one of the earliest known dinosaurs. This medium-sized predator measured about 3-6 meters (10-20 feet) in length and likely weighed between 210-350 kilograms (463-772 pounds). Named after rural worker Victorino Herrera, who discovered the first specimens in 1958, Herrerasaurus possesses a fascinating mix of primitive and derived features that has complicated paleontologists’ understanding of early dinosaur evolution. Its skull was relatively large with serrated, knife-like teeth perfect for slicing through flesh, while its forelimbs were equipped with powerful claws for grasping prey. Perhaps most notably, Herrerasaurus had a flexible joint in its lower jaw that allowed it to slide back and forth—a feature that helped it secure struggling prey, similar to some modern snakes. This combination of adaptations made Herrerasaurus a formidable hunter in its environment, capable of tackling prey that might have been significantly larger than itself.

Evolutionary Placement: Why Herrerasaurus Matters

The evolutionary position of Herrerasaurus has been the subject of considerable scientific debate, highlighting its importance in understanding dinosaur origins. When first described, some researchers classified it as a primitive theropod (the group that includes all carnivorous dinosaurs), while others considered it a basal saurischian (one of the two main dinosaur groups) that predated the theropod-sauropodomorph split. More recent analyses suggest Herrerasaurus likely represents one of the earliest dinosaurian branches, possessing features that would later become standard in theropod dinosaurs while retaining several primitive characteristics. The animal’s hip structure, for instance, shows the distinctive perforation in the acetabulum (hip socket) that defines all true dinosaurs, yet its hand retains five digits rather than the three seen in later theropods. This mosaic of features makes Herrerasaurus a crucial “transitional form” that helps paleontologists understand how the classic dinosaur body plan evolved from earlier archosaurs. Its study continues to illuminate the early radiation of dinosaurs and their rise to ecological dominance.

Hunting Adaptations: Built for the Kill

Herrerasaurus displayed impressive adaptations that made it an effective predator in the Triassic ecosystem. Its long, slender hindlimbs suggest it was capable of rapid pursuit, while its shorter forelimbs ended in distinctive hands with elongated fingers and curved claws ideal for grasping struggling prey. Unlike many later theropods, Herrerasaurus could pronate its hands (turn them palm-down), giving it greater flexibility when manipulating objects or subduing victims. The predator’s skull architecture supported powerful bite forces, with a hinge mechanism that allowed some movement of the bones, providing better grip on struggling prey. Its teeth were laterally compressed and serrated, similar to modern carnivores’ teeth, enabling efficient slicing through flesh. Interestingly, the relative shortness of its arms compared to later theropods suggests Herrerasaurus relied more on its powerful jaws to kill rather than grasping with its forelimbs, representing a somewhat different hunting strategy than that employed by later carnivorous dinosaurs. These adaptations collectively made Herrerasaurus a versatile and effective hunter in its environment, capable of targeting a range of prey sizes.

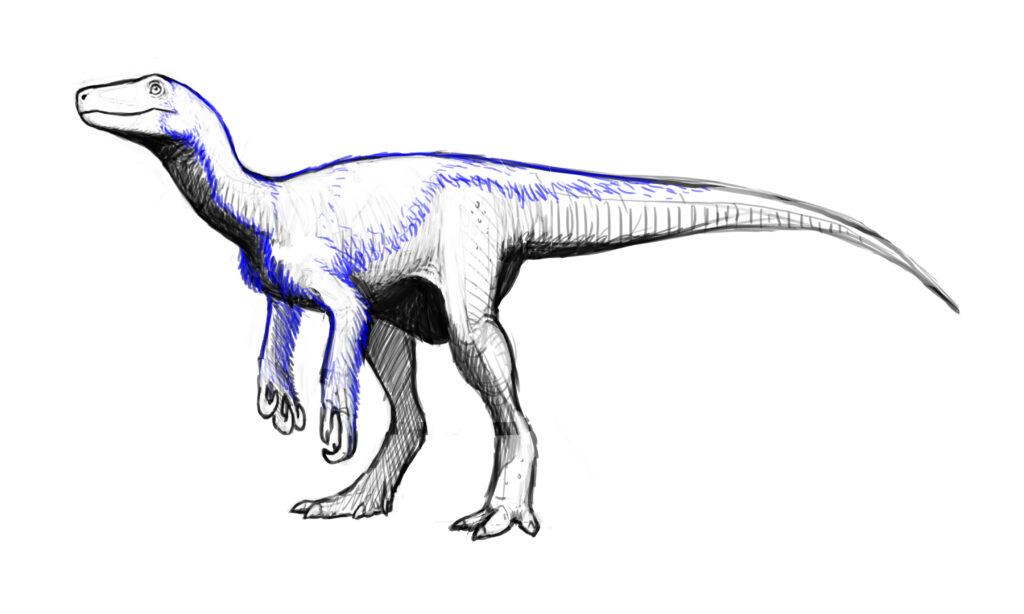

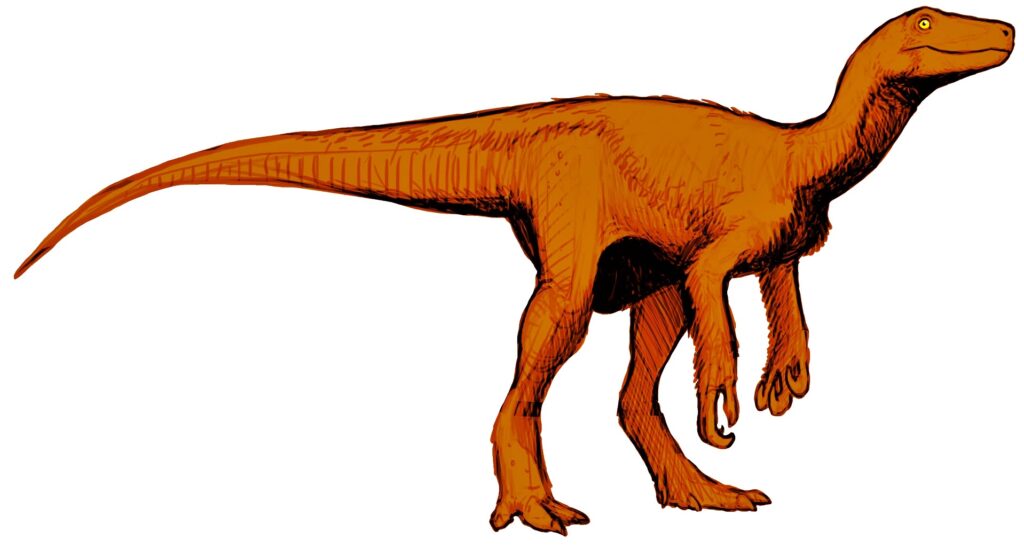

Staurikosaurus: The Brazilian Hunter

Closely related to Herrerasaurus was Staurikosaurus pricei, another early dinosaur that prowled what is now southern Brazil approximately 225-230 million years ago. Named from Greek words meaning “southern cross lizard” (referring to the constellation visible in the southern hemisphere), Staurikosaurus was notably smaller than its Argentine cousin, measuring about 2-2.5 meters (6.5-8 feet) in length. Despite being known from incomplete fossil material—primarily a partial skeleton lacking the skull—paleontologists have determined that Staurikosaurus shared many anatomical features with Herrerasaurus, suggesting similar predatory capabilities. Its lightweight, slender build indicates it was a swift runner adapted for chasing down smaller prey animals across the Triassic landscape. The discovery of Staurikosaurus was particularly significant as it represented one of the earliest known dinosaurs when first described in 1970, and along with Herrerasaurus, it forms part of the family Herrerasauridae—some of the first dinosaurs to evolve the predatory adaptations that would later become refined in theropods like Allosaurus and ultimately Tyrannosaurus.

Sanjuansaurus: The Newest Herrerasaurid

Discovered in the same Ischigualasto Formation that yielded Herrerasaurus, Sanjuansaurus gordilloi represents a more recently described member of the herrerasaurid family, named in 2010. Dating to approximately 231 million years ago, this predator shared its environment directly with Herrerasaurus, suggesting these related carnivores may have occupied slightly different ecological niches to reduce competition. Somewhat smaller than Herrerasaurus but larger than Staurikosaurus, Sanjuansaurus displays the characteristic features of herrerasaurids, including the distinctive hip structure and grasping hands. The discovery of Sanjuansaurus has been particularly valuable in confirming the diversity of early dinosaurian predators within a single ecosystem. The fossil includes elements not preserved in other herrerasaurid specimens, providing additional anatomical information about this important early dinosaur group. Paleontologists studying Sanjuansaurus have noted several unique anatomical features that distinguish it from Herrerasaurus despite their close relationship, including differences in the vertebrae and pelvis, suggesting that even at this early stage in dinosaur evolution, specialization and diversification were occurring among these pioneering predators.

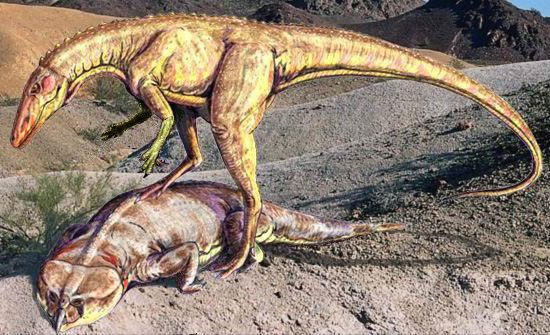

Eodromaeus: The Dawn Runner

Another significant Triassic predator that shared its environment with Herrerasaurus was Eodromaeus murphi, whose name aptly translates to “dawn runner.” Discovered in the Ischigualasto Formation of Argentina and dating to approximately 231-232 million years ago, this small dinosaur measured just 1-1.5 meters (3-5 feet) in length and weighed an estimated 5-10 kilograms (10-22 pounds). Despite its diminutive size, Eodromaeus displays many features that would later become characteristic of theropod dinosaurs, including serrated teeth, air spaces in its vertebrae, and a specialized wrist joint. Unlike the herrerasaurids, Eodromaeus appears to be more closely related to the line that would eventually give rise to both theropods and sauropodomorphs, potentially representing a very early stage in theropod evolution. Its lightweight frame and long hindlimbs suggest it was a swift, agile predator that likely hunted small vertebrates and perhaps large insects in the Triassic underbrush. The discovery of Eodromaeus has been crucial in helping paleontologists understand the earliest stages of dinosaur diversification, providing evidence that the basic body plans of major dinosaur groups were already beginning to emerge by the mid-Triassic.

Eoraptor: Predator or Omnivore?

One of the most enigmatic early dinosaurs that lived alongside Herrerasaurus was Eoraptor lunensis, whose name means “dawn thief.” Discovered in 1991 in Argentina’s Ischigualasto Formation and dating to approximately 231 million years ago, this small dinosaur measured about 1 meter (3.3 feet) in length and weighed approximately 10 kilograms (22 pounds). Initially classified as an early theropod due to its apparent predatory adaptations, including serrated teeth at the front of its jaws, more recent analyses have suggested Eoraptor may represent a very early sauropodomorph (the group that later gave rise to the giant long-necked dinosaurs) or a basal saurischian that predated the theropod-sauropodomorph split. The heterodont dentition of Eoraptor—featuring different types of teeth within the same jaw—suggests it may have been omnivorous, capable of eating both plant material and small animals. This dietary flexibility would have been advantageous in the variable Triassic environment and may represent the ancestral condition for early dinosaurs before they specialized into strict herbivores or carnivores. Regardless of its precise classification, Eoraptor provides a crucial glimpse into the earliest stages of dinosaur evolution when the boundaries between major groups remained blurry.

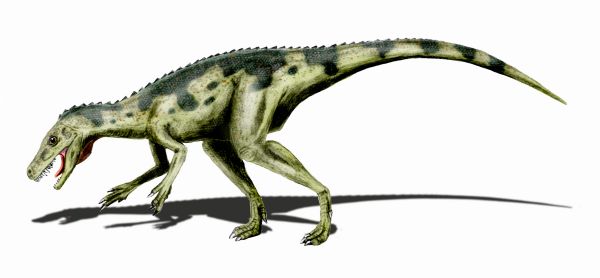

Chindesaurus: The North American Connection

While many early dinosaurs are known from South America, Chindesaurus bryansmalli represents an important North American member of the herrerasaurid family. Discovered in the Chinle Formation of Arizona and dating to approximately 216-228 million years ago, Chindesaurus demonstrates that these early predatory dinosaurs had achieved a wide geographic distribution by the Late Triassic period. Although known from incomplete remains, this dinosaur is estimated to have measured approximately 2-4 meters (6.5-13 feet) in length. Chindesaurus shares numerous anatomical features with its South American relatives, particularly in its pelvic structure, suggesting these animals maintained a consistent body plan across their range. The presence of herrerasaurids in North America is significant because it confirms that dinosaurs had already spread across much of Pangaea by the Late Triassic, taking advantage of the connected continental landmass. Paleontological studies of Chindesaurus and other North American Triassic fossils have revealed that early dinosaurs represented only a small component of these ecosystems, which remained dominated by other reptilian groups—a reminder that the “Age of Dinosaurs” began not with a bang but with a gradual ecological ascendance.

The Triassic Food Chain: What Did Herrerasaurus Eat?

The Triassic ecosystems inhabited by Herrerasaurus and its relatives were markedly different from the dinosaur-dominated landscapes of the later Mesozoic. Analysis of the Ischigualasto Formation has revealed a diverse community of potential prey animals for these early predators. The most abundant herbivores were rhynchosaurs—stocky, pig-sized reptiles with specialized beaks for processing tough plant material, which likely formed a significant portion of Herrerasaurus’ diet. Other potential prey included the early dinosauriform Silesaurus, various cynodonts (mammal relatives), and the dicynodont Ischigualastia. Herrerasaurus may have also targeted the early dinosaur Pisanosaurus, one of the earliest known ornithischians. Coprolites (fossilized dung) and rare stomach contents associated with predatory animals from this period suggest these hunters were opportunistic, taking whatever prey was available. Tooth mark evidence on some fossils indicates that Herrerasaurus employed a strategy of biting and pulling to tear flesh from carcasses, similar to modern Komodo dragons. Smaller herrerasaurids and other early dinosaurs like Eoraptor likely focused on different prey, including insects, small reptiles, and possibly even early mammaliaforms, creating a complex food web within these transitional ecosystems.

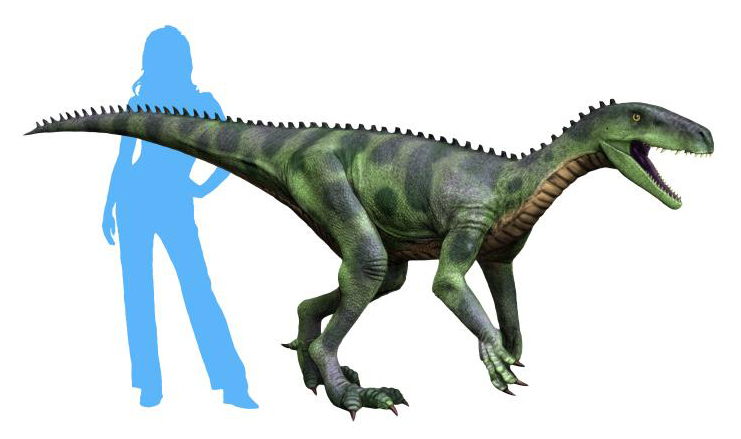

Competitors: Non-Dinosaurian Triassic Predators

Despite their advanced adaptations, Herrerasaurus and other early dinosaurian predators were not the apex hunters of their ecosystems. The Triassic landscapes were dominated by a diverse array of non-dinosaurian archosaurs and other reptiles that competed with these early dinosaurs for resources. Among the most formidable were the rauisuchians—large, quadrupedal predators like Saurosuchus and Prestosuchus that could reach lengths of 5-6 meters (16-20 feet) and likely occupied the apex predator niche in many environments. Another significant group was the ornithosuchids, including Riojasuchus, which combined crocodile-like features with the ability to walk on two legs. The bizarre poposaurs, such as Poposaurus and Shuvosaurus, represented another successful group of predatory archosaurs with dinosaur-like features. Even some of the larger cynodonts may have been carnivorous, creating multiple tiers of predators within these ecosystems. This intense competition may explain why early dinosaurs remained relatively rare components of Triassic faunas, comprising less than 5% of individuals in most fossil assemblages. It would take the end-Triassic mass extinction, which severely impacted many of these non-dinosaurian groups, to create the ecological opportunity for dinosaurs to achieve dominance in terrestrial ecosystems.

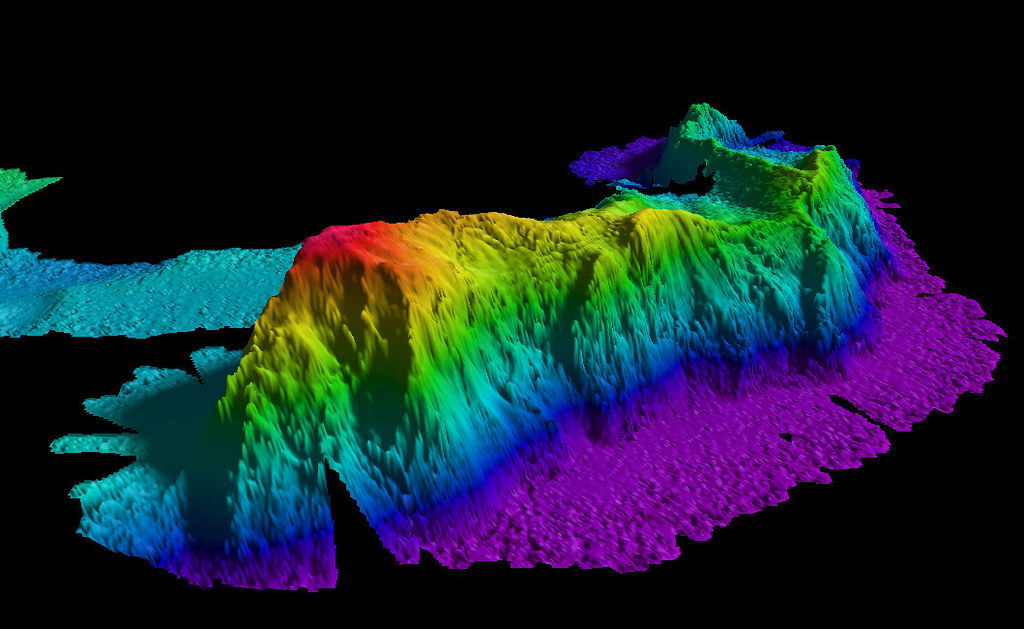

The Ischigualasto Formation: Window into the Dawn of Dinosaurs

The Ischigualasto Formation in northwestern Argentina represents one of paleontology’s most significant windows into the early evolution of dinosaurs. Dating to approximately 231-228 million years ago during the Carnian stage of the Late Triassic, this geological formation has yielded remarkably preserved fossils of Herrerasaurus, Eoraptor, Sanjuansaurus, Eodromaeus, and other crucial early dinosaurs. The conditions that created this exceptional fossil record included seasonal rivers and floodplains under a relatively dry climate with pronounced wet and dry seasons. Volcanic ash from nearby eruptions frequently blanketed the landscape, rapidly burying animals and plants, creating ideal conditions for fossil preservation. Paleoenvironmental studies indicate the region supported a diverse flora dominated by seed ferns, conifers, and cycad-like plants, creating a mosaic of gallery forests along waterways and more open areas between them. This environment would have provided varied hunting opportunities for predators like Herrerasaurus, which could have ambushed prey in densely vegetated areas or pursued them across more open ground. The Ischigualasto Formation and its contemporary, the slightly younger Los Colorados Formation, collectively document the first major radiation of dinosaurs, capturing the moment when these animals began their ascent toward ecological dominance.

The End-Triassic Extinction: Opportunity from Catastrophe

The evolutionary story of early dinosaurs like Herrerasaurus takes a dramatic turn at the close of the Triassic period, approximately 201 million years ago. The End-Triassic extinction event represents one of the five major mass extinctions in Earth’s history, likely triggered by massive volcanic eruptions associated with the breakup of the supercontinent Pangaea. These eruptions released vast amounts of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, leading to rapid climate change, ocean acidification, and widespread ecological disruption. In the aftermath, many dominant reptile groups were wiped out, clearing the way for dinosaurs to rise to ecological dominance during the Jurassic period. This pivotal shift allowed lineages like theropods, sauropodomorphs, and ornithischians to diversify and thrive across the globe.