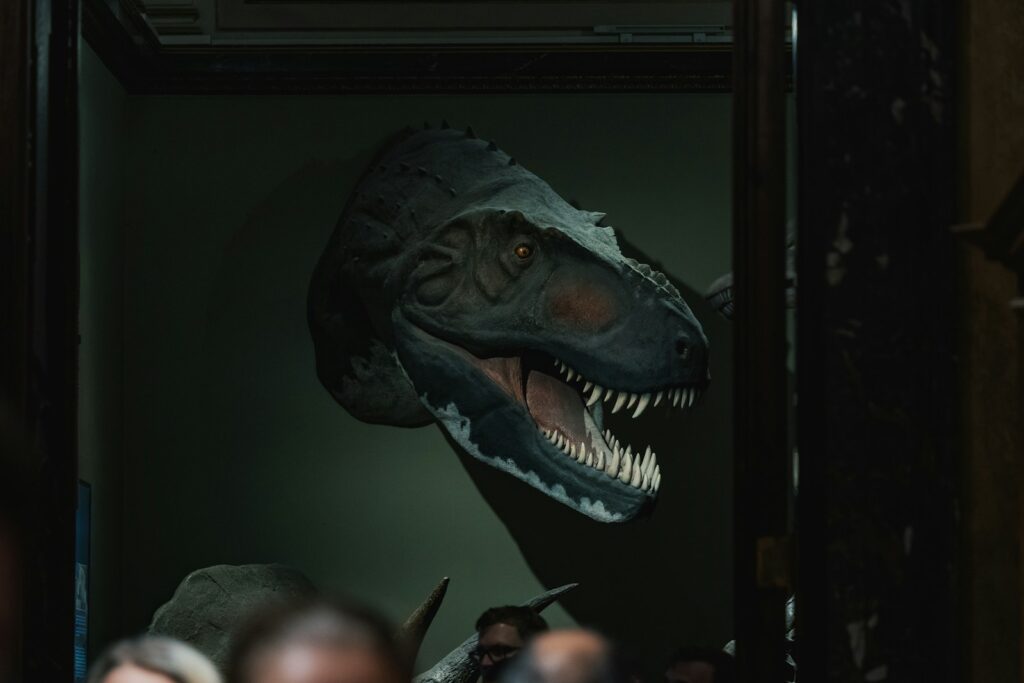

When “Jurassic Park” roared into theaters in 1993, it revolutionized how we visualize dinosaurs and sparked widespread interest in paleontology. Steven Spielberg’s blockbuster masterpiece, based on Michael Crichton’s novel, presented what seemed like scientifically accurate depictions of these prehistoric creatures. However, in the decades since its release, scientific discoveries have dramatically changed our understanding of dinosaurs. While the film deserves credit for its groundbreaking effects and for bringing dinosaurs into popular culture, many of its portrayals now appear outdated or were deliberately altered for dramatic effect. Let’s explore what Jurassic Park got wrong about dinosaurs, and how our scientific understanding has evolved.

The Feather-Free Fallacy

Perhaps the most significant inaccuracy in Jurassic Park is the complete absence of feathers on its dinosaurs. Scientific evidence now strongly indicates that many theropod dinosaurs, including Velociraptor and even possibly Tyrannosaurus rex, possessed feathers or feather-like structures. Fossil discoveries with preserved feather impressions, particularly from China’s Liaoning Province, have revolutionized our understanding of dinosaur appearance. These feathers weren’t necessarily for flight but likely served purposes including insulation, display, and potentially brooding behavior. The raptors in Jurassic Park, with their scaly, reptilian skin, represent an outdated view that existed when the film was made, though even then, some paleontologists were beginning to suspect feathered dinosaurs existed.

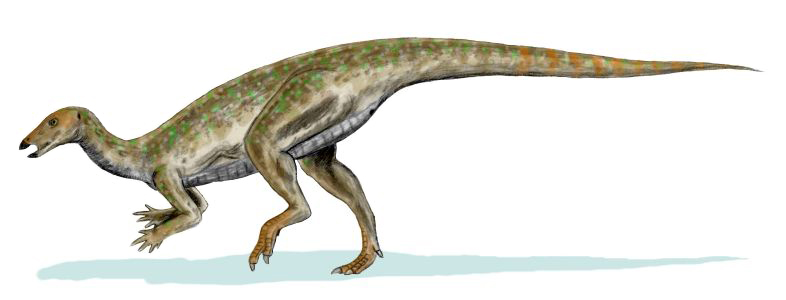

Velociraptor: Size and Geography Distortions

Jurassic Park’s Velociraptors bear little resemblance to their real-life counterparts. The actual Velociraptor was roughly the size of a turkey—standing about 1.6 feet tall and 6.8 feet long—significantly smaller than the human-sized predators depicted in the film. What moviegoers saw were actually more akin to Deinonychus or Utahraptor, larger dromaeosaurids that more closely matched the film’s portrayal in size. Additionally, Velociraptors were native to what is now Mongolia and China, not Montana where the film’s fossils were supposedly discovered. The film also omitted the fact that real Velociraptors had feathers and probably hunted alone or in small groups rather than in the highly coordinated packs shown on screen.

Dilophosaurus: The Fictionalized Spitter

The portrayal of Dilophosaurus in Jurassic Park was almost entirely fictional. In reality, this dinosaur was much larger than shown—growing up to 20 feet long, not the dog-sized creature in the film. There is absolutely no fossil evidence supporting the dramatic neck frill that expands when the dinosaur is threatened or the ability to spit venom at prey. These features were creative inventions to make the dinosaur more menacing and distinctive for the film. The actual Dilophosaurus was a significant predator of the Early Jurassic period, with two distinctive crests on its skull that likely served as display structures rather than any defensive mechanism. Its inclusion in the film, while memorable, represents one of the most heavily fictionalized dinosaur depictions in the franchise.

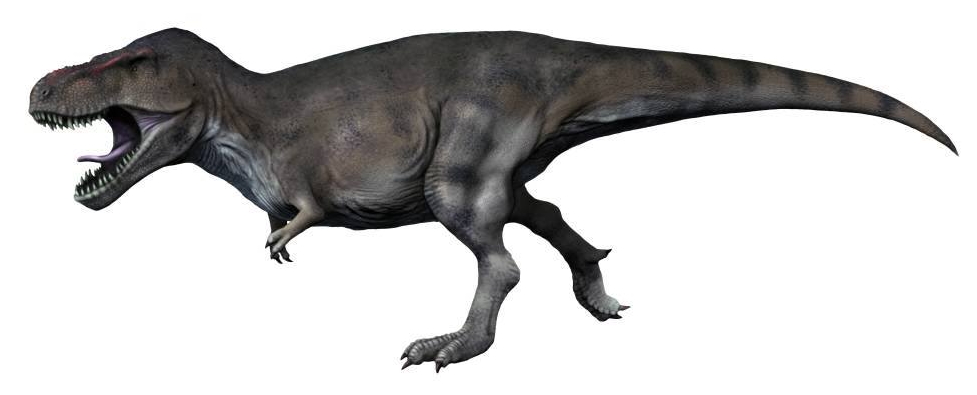

T. Rex: Vision and Movement

The famous scene where Dr. Alan Grant explains that T. rex’s vision is “based on movement” was a cinematic invention with no scientific backing. Current research suggests T. rex likely had excellent vision, comparable to that of modern birds of prey. The dinosaur probably possessed some of the best visual acuity among dinosaurs, with forward-facing eyes providing good depth perception crucial for hunting. Additionally, while the film’s T. rex could reach speeds of around 32 mph, more recent biomechanical studies suggest adult T. rex probably moved considerably slower, with top speeds estimated between 10-15 mph. The massive predator would have been physically incapable of the quick turns and agile movements depicted in the film due to its enormous body mass and the structural limitations of its skeleton.

Dinosaur Sounds and Vocalizations

The roars, screams, and calls of Jurassic Park’s dinosaurs were largely creative interpretations rather than scientific reconstructions. Since vocal organs rarely fossilize, paleontologists have limited direct evidence of what dinosaurs actually sounded like. The iconic T. rex roar was a mix of baby elephant, alligator, and tiger sounds, while raptor vocalizations incorporated tortoise mating sounds. Modern science suggests many dinosaurs may have made sounds more similar to today’s birds and crocodilians—their closest living relatives. Some dinosaurs likely produced low-frequency rumbles or closed-mouth vocalizations, while others might have used resonating chambers in their crests for communication. The dramatic, mammalian-like roars in the film, while thrilling, probably bear little resemblance to actual dinosaur vocalizations.

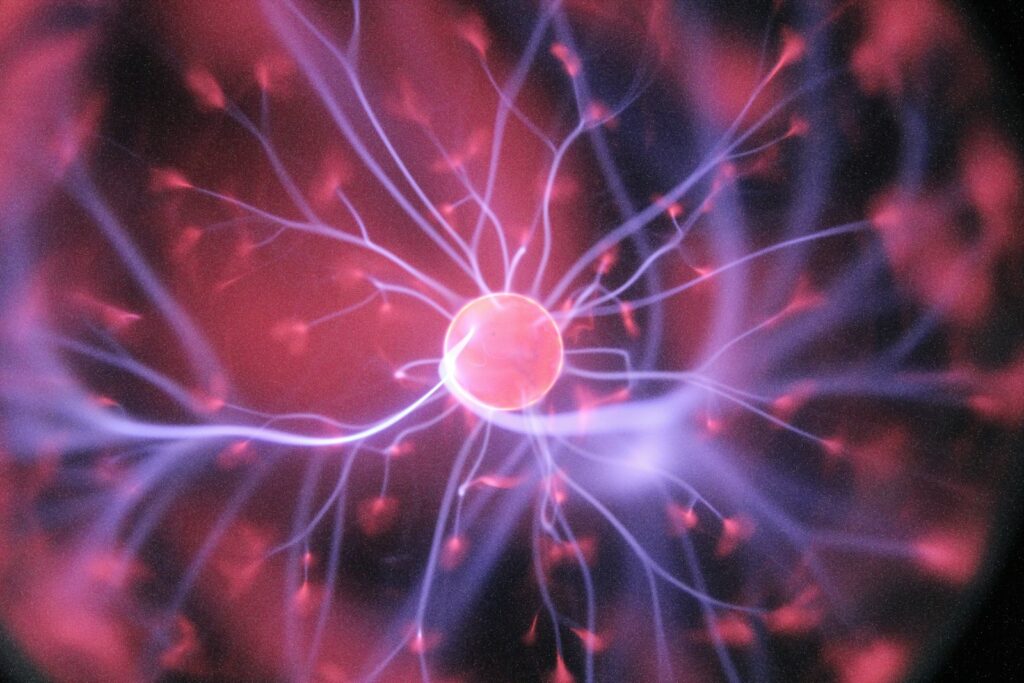

Genetic Resurrection Implausibilities

The film’s central premise—extracting dinosaur DNA from mosquitoes preserved in amber and using frog DNA to fill the gaps—contains significant scientific problems. DNA degrades relatively quickly, even in ideal preservation conditions, with a half-life of approximately 521 years. This means retrieving usable dinosaur DNA after 65+ million years is virtually impossible, even from specimens preserved in amber. Furthermore, using frog DNA to fill genomic gaps would be problematic as amphibians are very distantly related to dinosaurs. Birds, as direct descendants of theropod dinosaurs, would have been more logical donors. The film’s explanation for how complete dinosaurs were engineered from fragmentary genetic material greatly oversimplified the immense complexity of genetics and development, though this simplification was necessary for the story’s premise.

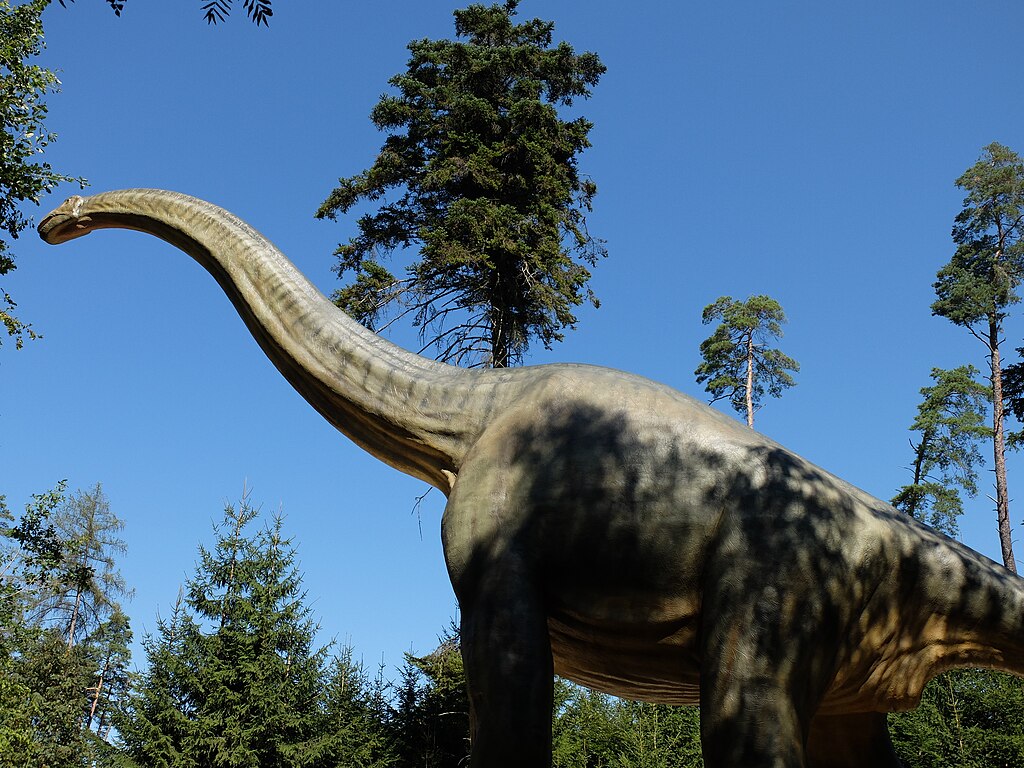

Brachiosaurus Posture and Behavior

The majestic Brachiosaurus scene when visitors first enter the park shows these long-necked giants rearing up on their hind legs to reach tall vegetation. While visually stunning, this portrayal is now considered inaccurate. Biomechanical studies suggest sauropods like Brachiosaurus couldn’t rear up as shown due to their center of gravity and vertebral structure. Additionally, the film depicted them as chewing their food, but sauropods lacked the appropriate dentition for chewing—they were likely gulp feeders who swallowed vegetation whole to be processed by gastroliths (stomach stones) and their extensive digestive system. The film’s Brachiosaurus also appears to have nostrils on top of its head, while fossil evidence indicates they were actually located on the side of the snout, similar to modern reptiles and birds.

Dinosaur Skin Textures and Colors

Jurassic Park presented most dinosaurs with reptilian, scaly skin in relatively conservative earth tones. Recent fossil discoveries with preserved skin impressions and pigment-containing cells called melanosomes have revealed a much more complex reality. Many dinosaurs likely had diverse skin coverings ranging from scales to feathers, often on the same animal. Color studies of fossil melanosomes suggest some dinosaurs displayed bright colors and complex patterns, possibly for camouflage, species recognition, or mating displays. Microraptor, for instance, appears to have had iridescent black feathers similar to modern crows. Psittacosaurus may have had countershading camouflage with a lighter belly and darker back. These vibrant, diverse appearances would have made the prehistoric world far more colorful than the predominantly green and brown creatures seen in Jurassic Park.

Dinosaur Intelligence and Social Behavior

While Jurassic Park’s portrayal of highly intelligent Velociraptors made for thrilling cinema, it significantly exaggerated dinosaur cognitive abilities. The film shows raptors problem-solving at near-human levels, opening doors and setting complex traps. Based on brain-to-body size ratios (encephalization quotients), even the most intelligent dinosaurs likely had cognitive abilities closer to modern birds or reptiles rather than primates or dolphins. That said, some dinosaurs were indeed relatively intelligent—particularly small, predatory theropods like Troodon, which had one of the highest brain-to-body ratios among dinosaurs. Social behavior in dinosaurs was also more complex than once thought, with evidence of herding behavior in many species and possible pack hunting in some theropods, though probably not with the sophisticated coordination depicted in the film.

Prehistoric Plant Life Inaccuracies

The film’s lush, tropical setting featured plant life that would have seemed familiar to modern viewers, but many plants shown wouldn’t have existed alongside dinosaurs. Flowering plants (angiosperms) only became widespread in the late Cretaceous period, yet they appear abundantly throughout the film’s Jurassic-themed park. The Mesozoic landscape would have been dominated by conifers, cycads, ginkgoes, ferns, and horsetails—creating an environment that would look quite alien to modern eyes. Grass, which appears in several scenes, didn’t evolve until near the end of the dinosaur era and wasn’t common until after the dinosaur extinction. The film’s portrayal of a prehistoric ecosystem more closely resembles modern tropical jungles than the actual plant communities that existed during the Mesozoic Era, when dinosaurs actually roamed the Earth.

Contemporaneous Dinosaur Species

Jurassic Park assembled dinosaurs from different time periods and geographic locations, creating an artificial ecosystem that never existed in nature. Tyrannosaurus rex and Triceratops lived during the late Cretaceous period (approximately 68-66 million years ago), while Brachiosaurus and Dilophosaurus were from the Jurassic period (approximately 150 million years ago)—meaning these species were separated by over 80 million years. This would be equivalent to humans coexisting with early mammals from the time of dinosaurs. Additionally, these dinosaurs came from different continents and ecosystems—Velociraptor from Asia, T. rex from North America, and others from various regions across the globe. The film justified this through the premise of genetic engineering, but this assemblage represents a Hollywood creation rather than any natural dinosaur community that ever existed.

Modern Scientific Advances Since Jurassic Park

In the decades since Jurassic Park’s release, paleontology has undergone something of a revolution, with thousands of new dinosaur species discovered and new technologies revealing unprecedented details about dinosaur biology. CT scanning has allowed scientists to examine dinosaur brains and sensory abilities without damaging fossils. Chemical analysis can now detect traces of original organic materials in some exceptionally preserved fossils, revealing information about soft tissues. Advances in comparative anatomy, biomechanics, and evolutionary developmental biology have transformed our understanding of dinosaur posture, movement, and growth. Perhaps most significantly, the discovery of numerous feathered dinosaur fossils has cemented the evolutionary connection between dinosaurs and birds, confirming that birds are, in fact, living dinosaurs. While Jurassic Park sparked interest in paleontology for a generation, the science has moved far beyond what was known when the film was created.

The Legacy and Impact of Jurassic Park’s Dinosaurs

Despite its scientific inaccuracies, Jurassic Park had an immeasurable positive impact on public interest in paleontology and dinosaur science. The film created what paleontologists call the “Jurassic Park effect”—a surge in funding, research, museum attendance, and student interest in dinosaur studies. Many of today’s working paleontologists cite the film as their inspiration for entering the field. The film also revolutionized how dinosaurs were visually represented, moving away from the slow, tail-dragging lizards of earlier portrayals toward more dynamic, active animals. Subsequent films in the franchise have updated some depictions—”Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom” (2018) finally included some feathered dinosaurs—but often prioritize consistency with earlier films over scientific accuracy. The original Jurassic Park, despite its flaws, deserves credit for bringing dinosaurs to life in the public imagination and sparking scientific curiosity that continues to drive paleontological discoveries today.

Conclusion

Jurassic Park remains a cinematic masterpiece that forever changed how we visualize dinosaurs, even if many of those visualizations have since been proven inaccurate. The film struck a delicate balance between the science available in the early 1990s and the demands of thrilling storytelling. While paleontologists might wince at featherless raptors or venom-spitting Dilophosaurus, they also acknowledge the film’s role in popularizing their field. As our understanding of dinosaurs continues to evolve through new fossil discoveries and analytical techniques, the gap between Jurassic Park’s dinosaurs and our scientific understanding widens. Yet rather than diminishing the film’s legacy, these advances highlight how science progresses—building on previous knowledge and continuously refining our picture of the prehistoric world. Jurassic Park may not have gotten all the details right, but it succeeded in something perhaps more important: inspiring generations to wonder about and study the magnificent animals that once ruled our planet.