The history of paleontology is filled with fascinating stories of discovery, interpretation, and reinterpretation. Scientists working with incomplete specimens and limited knowledge of prehistoric life have occasionally drawn conclusions that later proved incorrect. These misidentifications aren’t simply embarrassing errors—they represent the scientific method in action, as new evidence leads to a revised understanding. From dinosaur parts assembled incorrectly to fossils mistaken for mythological creatures, these paleontological plot twists have shaped our evolving picture of life’s history on Earth. Let’s examine some of the most remarkable cases where initial fossil identifications were later overturned, revealing surprising insights into ancient organisms.

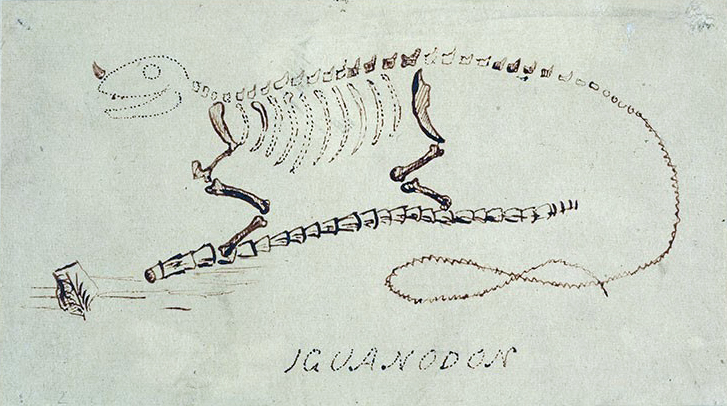

The “Terrible Hands” of Iguanodon

When Gideon Mantell discovered Iguanodon fossils in the 1820s, he made a significant error in reconstruction that persisted for decades. Mantell placed what he thought was a horn on the creature’s nose, giving it a rhinoceros-like appearance. The “horn” was a modified thumb spike that belonged on the dinosaur’s hand. This misplacement wasn’t corrected until the 1870s when multiple complete Iguanodon skeletons were discovered in a Belgian coal mine. The revelation transformed our understanding of this important early dinosaur, showing it had unusual hands with thumb spikes likely used for defense or gathering food. This case demonstrates how even pioneering paleontologists could be led astray when working with fragmentary remains.

Brontosaurus: The Dinosaur That Wasn’t (Then Was Again)

Perhaps the most famous case of fossil misidentification involves Brontosaurus, a name familiar to generations of dinosaur enthusiasts. In 1879, paleontologist O.C. Marsh named a new sauropod dinosaur Brontosaurus excelsus. However, in 1903, scientists determined that Brontosaurus was the same genus as the previously named Apatosaurus, and according to scientific naming rules, the older name Apatosaurus took precedence. For over a century, scientists considered “Brontosaurus” merely an incorrect name for Apatosaurus. But in a surprising twist, a comprehensive 2015 study analyzing numerous specimens concluded that Brontosaurus was indeed distinct enough from Apatosaurus to warrant its genus after all. This paleontological resurrection demonstrates how advancing analytical techniques can sometimes validate earlier classifications.

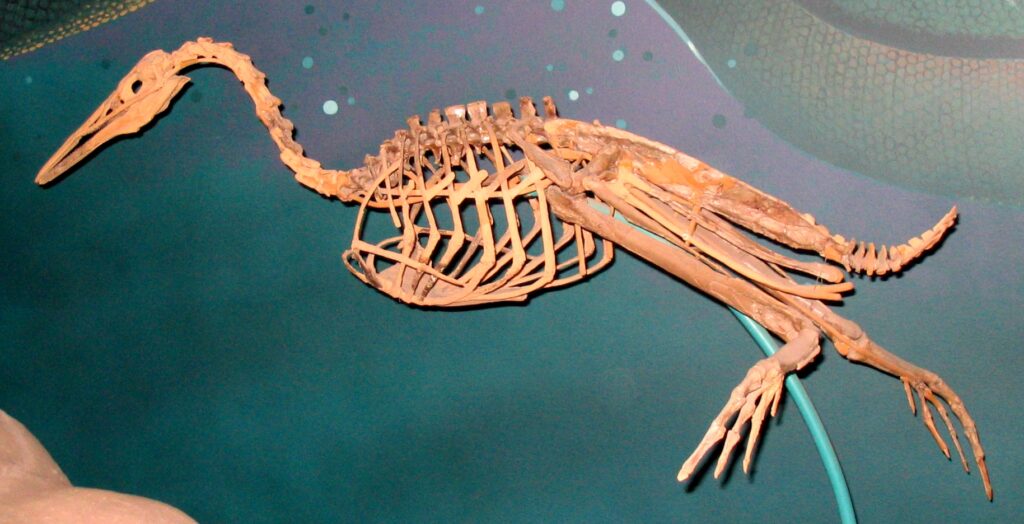

Hesperornis: The Bird That Wasn’t a Diver

When Hesperornis fossils were first discovered in the 1870s, scientists recognized them as ancient birds but incorrectly interpreted their lifestyle. Based on their toothed beaks and leg structure, early paleontologists classified them as specialized diving birds similar to modern loons or grebes. However, further analysis of their skeletal structure in the late 20th century revealed that Hesperornis couldn’t fold its legs sideways like modern diving birds. Instead, its legs extended straight backward, making it unable to walk effectively on land. Modern interpretations suggest Hesperornis was more like today’s penguins in locomotion, propelling itself underwater with powerful legs while being awkward on land. This reinterpretation significantly changed our understanding of bird evolution during the Cretaceous period.

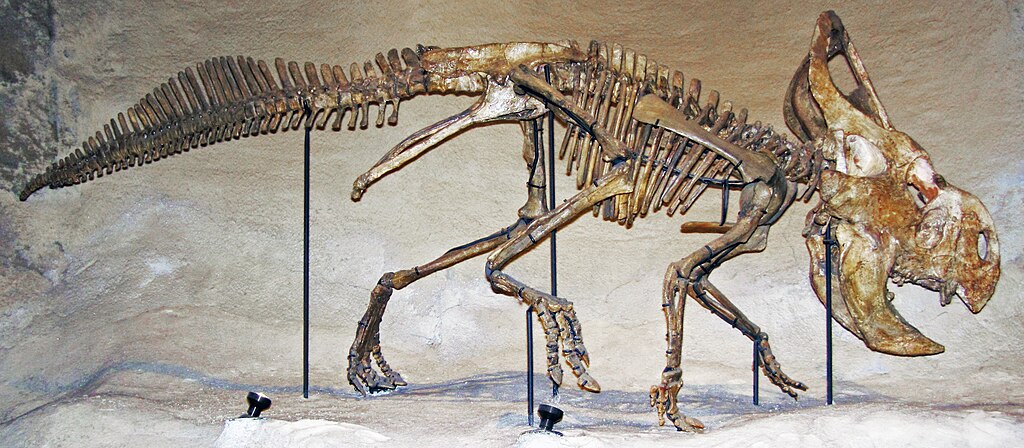

The Oviraptor: Falsely Accused “Egg Thief”

When Roy Chapman Andrews discovered the first Oviraptor skeleton in Mongolia in 1923, it was found atop what appeared to be a nest of Protoceratops eggs. This led to its name, Oviraptor, meaning “egg thief,” as scientists assumed it had been caught in the act of stealing another dinosaur’s eggs. For decades, this interpretation persisted, painting Oviraptor as a nest-raiding villain. However, in the 1990s, additional discoveries of Oviraptor skeletons with identical eggs revealed the truth: the original specimen wasn’t stealing eggs—it was protecting its own nest. The “stolen” eggs belonged to Oviraptor itself, and the animal likely died while brooding its eggs, possibly buried by a sandstorm. This discovery not only cleared Oviraptor’s reputation but also provided important evidence of bird-like brooding behavior in dinosaurs.

Hyracotherium: From “Rabbit-Like” to Horse Ancestor

When first discovered in 1841 by Richard Owen, the small fossil mammal he named Hyracotherium was thought to be related to modern hyraxes (hence the name, meaning “hyrax-like beast”). Owen based this on the creature’s small size and certain dental features. It wasn’t until decades later that paleontologists recognized this animal was an early ancestor of modern horses, part of the evolutionary lineage that would eventually produce Equus. Often later called Eohippus (“dawn horse”), this animal stood only about 2 feet tall with multiple toes rather than hooves. The reclassification of Hyracotherium represents one of the most significant taxonomic revisions in paleontology and became a classic example of evolutionary change that Darwin and his successors used to illustrate natural selection.

The Archaeoraptor Fiasco

In 1999, National Geographic magazine published an article featuring “Archaeoraptor liaoningensis,” supposedly a critical missing link showing the evolution from dinosaurs to birds. The fossil appeared to show features of both groups, making it an exciting discovery. However, within months, scientists determined that the specimen was a fraudulent composite—a chimera created by combining parts from at least two different fossils: the body of a primitive bird and the tail of a dromaeosaurid dinosaur. While the forgery was embarrassing for those involved, the individual fossils that made up the fake were themselves scientifically valuable. The Archaeoraptor incident highlighted the problems with fossils from private markets without proper provenance and emphasized the importance of rigorous peer review before announcing major scientific discoveries.

Giant’s Shoulders: Scythian Griffins and Greek Myths

In ancient Greece and throughout Central Asia, fossils of Protoceratops and other ceratopsian dinosaurs were likely the inspiration for myths about griffins—creatures with the body of a lion and the head of an eagle. The beaked face, neck frill, and four-legged body of these dinosaur fossils, when discovered by ancient peoples, matched descriptions of griffins remarkably well. Similarly, the large fossils of mammoths and mastodons found in Greece and Italy probably inspired myths of giants and cyclopes. The single large nasal opening in elephant skulls could easily be misinterpreted as a single eye socket by people unfamiliar with elephant anatomy. These misidentifications occurred long before the development of paleontology as a science, demonstrating how humans have always attempted to make sense of fossil evidence using the knowledge frameworks available to them.

Basilosaurus: The “King Lizard” That Was a Whale

When the enormous fossil vertebrae of Basilosaurus were first discovered in Louisiana in the 1830s, naturalist Richard Harlan believed they belonged to a marine reptile, possibly related to mosasaurs or plesiosaurs. He named the creature Basilosaurus, meaning “king lizard,” reflecting this reptilian classification. However, anatomist Richard Owen later examined the fossils and recognized distinctive mammalian features, particularly in the teeth. Owen correctly identified Basilosaurus as an early whale, not a reptile at all. Despite this reclassification, the original name remained according to taxonomic rules. At 50-60 feet long with a serpentine body, Basilosaurus was unlike modern whales in many ways, having small hind limbs and differentiated teeth. This case shows how preconceptions about what kinds of animals existed in different periods can influence initial interpretations.

The Piltdown Man Hoax

While not strictly a natural misidentification, the Piltdown Man deserves mention as one of the most infamous deliberate fossil frauds. In 1912, amateur archaeologist Charles Dawson claimed to have discovered the “missing link” between apes and humans in Piltdown, England. The skull fragments appeared to show a creature with a human-sized brain case but an ape-like jaw. For 40 years, Piltdown Man was accepted by many as an important human ancestor, influencing theories of human evolution. In 1953, modern dating techniques revealed the truth: the “fossil” was a modern human skull combined with an orangutan jawbone, chemically treated to appear ancient. The perpetrator’s identity remains debated, though Dawson is the prime suspect. The Piltdown Man case demonstrates how confirmation bias can affect scientific judgment, as the fraud aligned with contemporary expectations that human brain development preceded other modern features.

Hallucigenia: The Upside-Down Oddball

When paleontologist Simon Conway Morris first described the bizarre Cambrian creature Hallucigenia in 1977, he was working with limited fossil evidence that led to a fundamentally incorrect reconstruction. The animal was portrayed upside-down, with what were thought to be tentacles on its back and strange stilt-like legs supporting it. The creature’s name reflected how utterly strange it appeared. However, in the 1990s, better-preserved specimens and related animals discovered in China enabled scientists to properly orient Hallucigenia. What had been interpreted as tentacles were defensive spines on its back, and the “legs” were paired walking appendages. Even more surprisingly, the head and tail had been reversed in earlier reconstructions. This dramatic reinterpretation transformed Hallucigenia from an incomprehensible oddity to a recognizable member of the velvet worm family, demonstrating how fragmentary fossils can lead even careful scientists astray.

Anomalocaris: The “Abnormal Shrimp” That Wasn’t

The reconstruction of Anomalocaris represents one of the most remarkable reassemblies in paleontological history. Initially, different parts of this Cambrian predator were described as separate animals: its frontal appendages were thought to be unusual shrimp (hence the name “abnormal shrimp”), its circular mouth was classified as a jellyfish called Peytoia, and its segmented body was identified as a sea cucumber named Laggania. It wasn’t until the 1980s that paleontologist Harry Whittington and colleagues realized these “different animals” were parts of a single creature—the largest predator of the Cambrian seas at nearly one meter long. This remarkable case of misidentification resulted from the unusual body plan of Anomalocaris, which had no close modern analogues, and the fragmentary nature of many Cambrian fossils. The reassembly of Anomalocaris revolutionized our understanding of early animal evolution and the ecology of Cambrian oceans.

Tully Monster: The Continuing Mystery

The Tully Monster (Tullimonstrum gregarium) remains one of paleontology’s most perplexing cases of uncertain identification. Discovered in Illinois coal deposits in 1958, this strange creature had a torpedo-shaped body, eyes on stalks, and a long proboscis ending in what appears to be a toothed claw. For decades, scientists couldn’t confidently place it in any known animal group. In 2016, a study suggested it was a vertebrate related to lampreys, which would make it an important early vertebrate fossil. However, subsequent analyses in 2017 and 2020 contradicted this classification, suggesting it might be an invertebrate after all. Unlike other cases on this list, the Tully Monster represents an ongoing scientific debate rather than a resolved misidentification. This continuing uncertainty highlights how some fossil organisms defy easy classification, especially when they represent body plans that have no close modern analogues.

Helicoprion: The Spiral-Toothed Mystery

When the bizarre spiral-shaped fossils of Helicoprion were first discovered in the late 19th century, paleontologists were utterly baffled. These coiled arrangements of teeth, resembling circular saw blades, defied easy explanation. Early reconstructions placed the spiral tooth whorl in various positions: projecting from the snout, on the dorsal fin, or even as an elaborate tail structure. Without a complete skeleton, scientists could only speculate about how these structures functioned in the living animal. Modern analysis finally solved the mystery in 2013 when CT scans of better specimens revealed that Helicoprion was a relative of modern ratfish, with the spiral tooth whorl located within its lower jaw. As the animal grew, it retained its old teeth in this spiral configuration rather than shedding them. This case illustrates how isolated, unusual structures can be nearly impossible to interpret correctly without more complete fossil evidence.

Conclusion: The Evolving Nature of Fossil Interpretation

These fascinating cases of fossil misidentification remind us that paleontology is a dynamic science constantly refining its understanding as new evidence emerges. Far from undermining the field’s credibility, these revisions demonstrate the self-correcting nature of scientific inquiry. Early paleontologists worked with fragmentary evidence and limited comparative material, making their achievements remarkable despite occasional errors. Today’s scientists benefit from advanced technologies like CT scanning, molecular analysis, and computer modeling that help resolve mysteries their predecessors couldn’t tackle. The story of fossil misidentifications teaches us humility about our current knowledge while celebrating the progress we’ve made in understanding Earth’s ancient inhabitants. Each revised interpretation brings us closer to accurately reconstructing the remarkable diversity of life that preceded our own.