The question of whether dinosaurs could climb trees takes us back to a time when these magnificent creatures ruled our planet. For generations, we’ve imagined dinosaurs primarily as ground-dwelling giants, but recent paleontological discoveries have dramatically shifted this perspective. The ability to climb trees would have offered dinosaurs numerous advantages—from escaping predators to accessing new food sources—and the evidence suggests that some species indeed possessed this capability. This article explores the fascinating evidence, anatomical adaptations, and scientific debates surrounding arboreal dinosaurs, offering a glimpse into yet another remarkable aspect of these ancient animals.

The Science of Identifying Tree-Climbing Abilities

Determining whether a dinosaur could climb trees presents paleontologists with significant challenges, as behavior doesn’t fossilize directly. Instead, scientists must examine skeletal adaptations that would facilitate climbing, such as specialized limbs, claws, and body proportions. Researchers also study modern tree-climbing animals to identify anatomical patterns that correlate with arboreal abilities. Comparative anatomy plays a crucial role, allowing scientists to recognize features like curved claws, grasping limbs, and specific joint configurations that would enable a dinosaur to navigate vertical surfaces. Additionally, paleontologists examine the environmental context of fossil discoveries, considering whether the prevalent ecosystem would have provided opportunities and advantages for tree-climbing behaviors.

Microraptor: The Four-Winged Tree Glider

Perhaps one of the most compelling examples of a tree-climbing dinosaur is Microraptor, a small feathered dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous period. This remarkable creature possessed four wings—one pair on its arms and another on its legs—suggesting it was adapted for gliding between trees. Microraptor’s curved claws and limb proportions closely resemble those of modern tree-dwelling birds, providing strong evidence for an arboreal lifestyle. Studies of its fossilized remains indicate it had the perfect anatomical features for perching on branches, including a foot structure similar to that of modern birds. Scientists believe Microraptor likely climbed trees to reach launching points before gliding to adjacent trees, representing an important evolutionary step in the development of avian flight.

Scansoriopterygids: The Specialized Tree-Climbers

The Scansoriopterygidae family represents some of the most specialized tree-climbing dinosaurs yet discovered. These small, bird-like dinosaurs possessed elongated fingers and unusual proportions that appear specifically adapted for an arboreal lifestyle. Yi qi, one notable member of this family, had a bat-like membrane stretched between an elongated finger and its body, suggesting it may have been capable of gliding between trees. Another member, Epidexipteryx, had proportionally long arms and specialized hands that would have been perfect for grasping branches. The name “Scansoriopterygidae” itself reflects these abilities, as “scansorial” refers to climbing adaptations. These dinosaurs lived during the Late Jurassic period and represent some of the most convincing examples of dinosaurs adapted specifically for life in the trees.

Dromaeosaurids: Raptors in the Branches

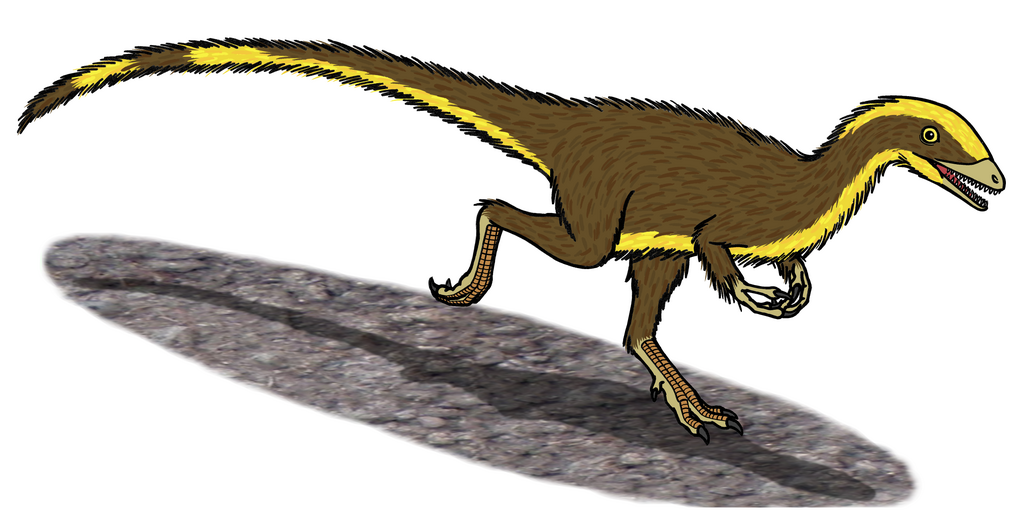

Dromaeosaurids, commonly known as “raptors,” show several anatomical features suggesting some species may have been capable tree-climbers. These predatory dinosaurs possessed curved claws, not only the famous sickle claw on their feet but also recurved claws on their hands that would have been useful for gripping branches. Their relatively small size and lightweight skeletons would have made navigating through trees physically possible for many species. Studies of fossils like Sinornithosaurus and Microraptor (which is also classified as a dromaeosaurid) reveal proportions and joint mobility compatible with climbing abilities. While larger dromaeosaurids like Velociraptor were likely primarily ground-dwelling, their smaller relatives may have regularly ventured into the canopy, possibly using trees as hunting perches or as refuges from larger predators.

Early Birds and the Tree-Down Theory of Flight

The earliest birds, which evolved from small theropod dinosaurs, show clear adaptations for tree dwelling that shed light on the arboreal capabilities of their dinosaur ancestors. Archaeopteryx, often considered the earliest known bird, possessed features suggesting it could perch on branches, including a reversed first toe that would help with gripping. These adaptations support the “trees-down” theory of flight evolution, which proposes that flight evolved from gliding between trees rather than running along the ground. If this theory is correct, it implies that the dinosaur ancestors of birds must have been capable tree-climbers. The presence of tree-climbing abilities in the dinosaur-bird transition provides crucial context for understanding how powered flight eventually evolved, suggesting that arboreal adaptations preceded the development of true flight.

Heterodontosaurids: Small Herbivores with Climbing Potential

Heterodontosaurids were small ornithischian dinosaurs that some paleontologists believe may have possessed tree-climbing abilities. These dinosaurs had relatively small bodies, proportionally long arms, and grasping hands that could potentially have been used for climbing. Species like Heterodontosaurus tucki had five fingers with the ability to grasp objects, a feature unusual among ornithischian dinosaurs. Recent research has suggested that some heterodontosaurids had shoulders and forearms with mobility ranges that would facilitate climbing motions. While not as specialized for arboreal life as some theropods, these adaptations may have allowed heterodontosaurids to climb into trees occasionally, perhaps to escape predators or access food sources like fruits or leaves that were unavailable on the ground.

Alvarezsaurids: Potential Branch-Climbers

Alvarezsaurids represent another group of dinosaurs with possible tree-climbing capabilities. These unusual theropods had distinctively short but powerful forelimbs with a single, enlarged claw that could have been used for gripping tree trunks or branches. Though initially their arms were thought to be specialized for breaking into insect nests, some researchers now suggest they may have also facilitated a partially arboreal lifestyle. The lightweight build and relatively small size of many alvarezsaurids would have made tree climbing physically feasible. Species like Mononykus and Shuvuuia had body proportions that wouldn’t have precluded climbing activities, though they were likely not as specialized for arboreal life as scansoriopterygids or certain dromaeosaurids. These adaptations may have allowed alvarezsaurids to exploit resources unavailable to strictly terrestrial dinosaurs.

Oviraptorosaurs: Feathered Climbers?

Oviraptorosaurs, with their parrot-like beaks and feathered bodies, show several features consistent with potential tree-climbing abilities. These theropod dinosaurs had relatively long arms, curved claws, and in some cases, proportions similar to modern climbing animals. Their shoulder joints allowed for a wide range of motion, which would have been beneficial for navigating through branches. Some species, like Caudipteryx, were relatively lightweight and possessed features that would not have impeded climbing behavior. The presence of pennaceous feathers on their limbs, which predated flight capabilities, may have provided additional grip when moving through trees. While not all oviraptorosaurs were necessarily arboreal, the anatomical evidence suggests that at least some species could have ventured into trees opportunistically.

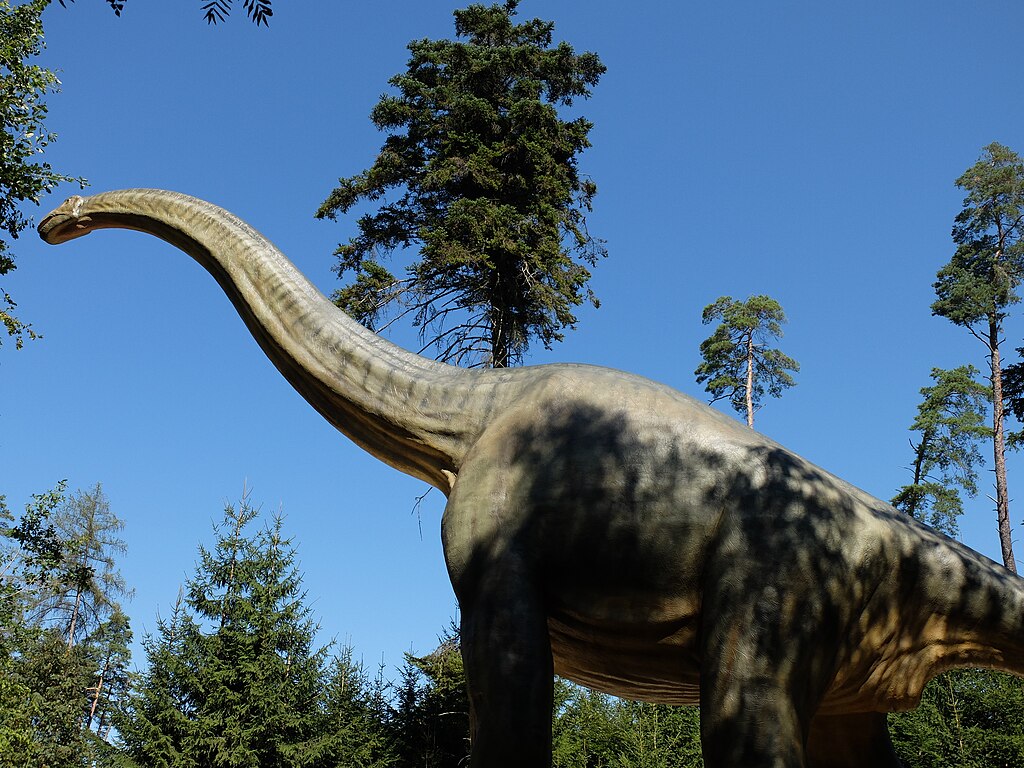

The Size Factor: Why Larger Dinosaurs Couldn’t Climb

Physics and biomechanics placed definite limitations on which dinosaurs could climb trees, with size being the most obvious restricting factor. Large dinosaurs like Brachiosaurus or Tyrannosaurus Rex were absolutely incapable of climbing due to their massive weight, which would have made it impossible for tree branches to support them and for their muscles to lift such bulk vertically. The square-cube law, which states that as an animal’s size increases, its volume and mass grow much faster than the cross-sectional area of its limbs, made climbing physically impossible beyond certain size thresholds. Additionally, larger dinosaurs typically had limb proportions and joint configurations optimized for supporting weight rather than for the flexibility needed in climbing. For tree-climbing capabilities, dinosaurs generally needed to be relatively small, typically weighing less than 15 kilograms, though exact limits would have varied based on specific adaptations and tree types available.

Modern Analogues: What Living Animals Tell Us

Studying modern tree-climbing animals provides crucial insights into identifying arboreal adaptations in dinosaur fossils. Animals like squirrels, chameleons, and various birds offer living examples of the diverse anatomical solutions that enable tree climbing. For instance, many modern climbing animals have opposable digits or specialized claws that facilitate gripping branches, features that can be recognized in fossil remains of certain dinosaurs. Geckos use microscopic setae on their toes to adhere to surfaces, demonstrating that climbing adaptations can be subtle and not always preserved in fossils. Modern birds, as the direct descendants of dinosaurs, show how feathers can aid in balance and movement through trees. The various climbing strategies employed by living animals—from the brachiation of gibbons to the vertical trunk-climbing of woodpeckers—help paleontologists interpret the functional significance of dinosaur anatomical features in the context of arboreal capabilities.

Controversial Cases: Debated Tree-Climbers

Several dinosaur species remain at the center of ongoing debates about their arboreal capabilities. Compsognathus, a small theropod, has been suggested by some researchers to have had climbing abilities based on its size and limb proportions, while others argue its anatomy indicates a purely terrestrial lifestyle. Similarly, Epidendrosaurus (also called Scansoriopteryx) has features strongly suggestive of tree-climbing, but the interpretation of its lifestyle remains contentious among some paleontologists. The small ceratopsian Psittacosaurus has been proposed as an occasional climber by certain studies based on limb mobility, though this interpretation has been met with skepticism. Archaeopteryx continues to generate debate regarding how arboreal it truly was, with some studies suggesting it was primarily ground-dwelling despite its bird-like features. These controversial cases highlight the challenges in definitively establishing behavior patterns from fossil evidence and underscore the nuanced nature of paleontological interpretation.

Evolutionary Advantages of Tree-Climbing

Tree-climbing abilities would have conferred significant evolutionary advantages to dinosaurs capable of this behavior. Perhaps most importantly, trees provided a refuge from ground-dwelling predators, allowing smaller dinosaurs to escape threats they couldn’t outrun or fight. The arboreal environment also offered access to different food sources, including fruits, leaves, seeds, and insects that weren’t available on the ground, potentially reducing competition for resources. Trees could have served as nesting sites, protecting eggs and young from predators and environmental hazards. For predatory dinosaurs, climbing abilities may have enabled ambush hunting strategies, allowing them to drop onto prey from above. Additionally, trees could have provided shelter from extreme weather conditions and served as resting places safe from nocturnal predators. These advantages help explain why tree-climbing adaptations evolved independently multiple times across different dinosaur lineages, representing a successful ecological strategy for smaller species.

Fossil Evidence: Tracks and Preserved Specimens

Beyond skeletal adaptations, paleontologists occasionally discover more direct evidence of dinosaur climbing behaviors. In rare cases, scratch marks preserved in fossilized tree trunks may indicate climbing activity, though such traces can be difficult to attribute definitively to specific animals. The Liaoning deposits in China, famous for their exceptionally preserved fossils, have yielded specimens of small dinosaurs preserved with their limbs in positions suggestive of climbing or perching. Some fossils show dinosaurs preserved in association with ancient trees, though taphonomic processes (how organisms become fossilized) can create misleading associations. Perhaps most telling is the discovery of dinosaur nests in what would have been elevated positions, suggesting that the parents accessed these locations by climbing. While such direct evidence remains relatively scarce, each new discovery adds to our understanding of the diverse locomotor capabilities of different dinosaur species.

The Future of Research on Arboreal Dinosaurs

Research into tree-climbing dinosaurs continues to evolve with new methodologies and discoveries transforming our understanding. Advanced biomechanical modeling using computer simulations now allows researchers to test hypotheses about climbing capabilities based on fossil measurements and muscle attachment sites. CT scanning technology provides unprecedented views of internal bone structures, revealing adaptations not visible on the surface. Continuing discoveries in previously unexplored regions may yield new examples of arboreal dinosaurs, particularly in fossil beds with exceptional preservation. Multidisciplinary approaches combining paleontology with ecology, evolutionary biology, and comparative anatomy promise to provide more nuanced interpretations of dinosaur behavior. The application of machine learning to analyze patterns across thousands of specimens may identify subtle climbing adaptations previously overlooked. As these research frontiers advance, our picture of dinosaur diversity continues to expand, revealing an ancient world where dinosaurs not only walked the earth but also climbed through the treetops.

Conclusion

The evidence strongly suggests that yes, some dinosaurs could indeed climb trees. From the specialized scansoriopterygids to the gliding microraptor, numerous smaller dinosaur species possessed anatomical adaptations that would have enabled arboreal capabilities. While massive dinosaurs remained firmly planted on the ground due to physical constraints, their smaller relatives exploited the evolutionary advantages of accessing the treetops. As paleontological techniques continue to advance, we’re gradually uncovering more details about these climbing dinosaurs, adding rich new dimensions to our understanding of prehistoric ecosystems. Far from being limited to a two-dimensional existence, dinosaurs occupied diverse niches—from underground burrows to the highest branches—demonstrating once again the remarkable adaptability that characterized their 165-million-year reign on Earth.