Dinosaurs have captivated human imagination since their fossils were first scientifically described in the early 19th century. However, the visual representations of these prehistoric creatures have undergone dramatic transformations over time. Early artistic interpretations of dinosaurs often appear comically inaccurate to modern viewers, featuring lumbering lizards with dragging tails and anatomical impossibilities. These misrepresentations weren’t simply the result of poor artistry but reflected the limited scientific understanding and cultural biases of their times. This article explores the fascinating evolution of dinosaur depictions and explains why early paleoart looks so amusingly wrong to our contemporary eyes.

The Victorian Foundation: When Dinosaurs Were First Visualized

The first scientifically-informed dinosaur reconstructions emerged in Victorian England, most famously with Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins’ Crystal Palace sculptures unveiled in 1854. These representations, guided by anatomist Richard Owen, depicted dinosaurs like Iguanodon as elephantine quadrupeds with rhinoceros-like horns on their snouts (which were actually thumb spikes). The Crystal Palace dinosaurs reflected the best scientific understanding of the time, when dinosaurs were conceptualized as oversized reptiles rather than a diverse group of animals with unique adaptations. Scientists had very fragmentary fossil evidence to work with, often just a few bones, and filled in the massive gaps with assumptions based on living reptiles. These early reconstructions served their purpose of making abstract scientific discoveries tangible to the public, despite what we now recognize as glaring inaccuracies in posture, proportions, and anatomical details.

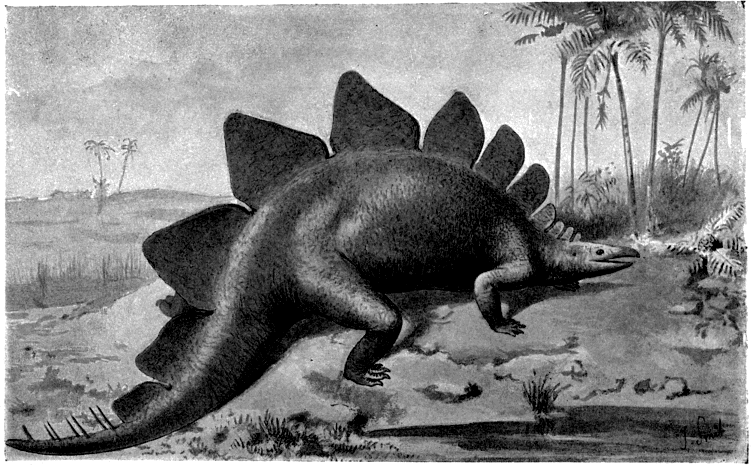

The Lizard Stereotype: Reptilian Assumptions Gone Wrong

Early paleontologists and artists operated under what scientists now call the “lizard stereotype,” automatically assuming dinosaurs functioned like scaled-up modern reptiles. This fundamental misconception led artists to depict dinosaurs with sprawling limbs, dragging tails, and generally lethargic postures reminiscent of crocodiles and lizards. The word “dinosaur” itself, coined by Richard Owen in 1842, means “terrible lizard,” reinforcing this reptilian association. This comparison to modern reptiles wasn’t entirely unreasonable at the time, as dinosaurs are indeed reptiles in a broad taxonomic sense. However, dinosaurs evolved numerous specializations that make them quite different from living reptiles, including upright limb posture, diverse metabolic adaptations, and in many cases, complex social behaviors. The assumption that ancient meant primitive further reinforced depictions of dinosaurs as slow, cold-blooded creatures with minimal intelligence or adaptability.

The Dragging Tail Misconception

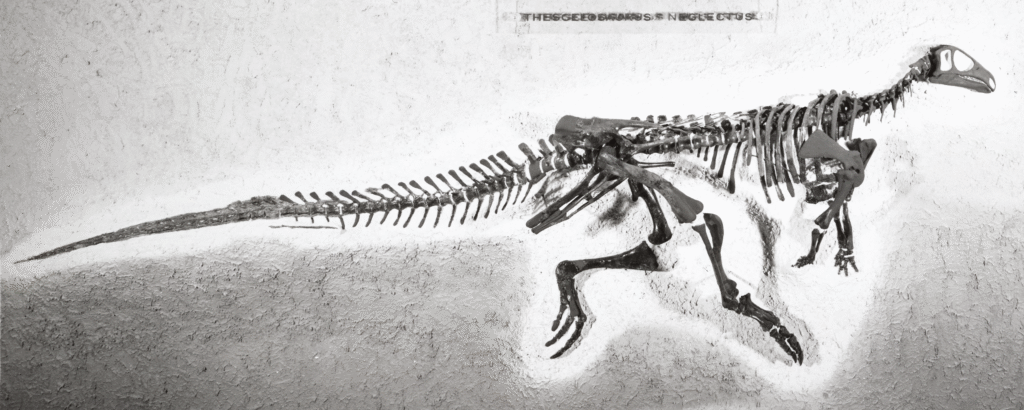

Perhaps no single feature of early dinosaur art appears more ridiculous to modern viewers than the ubiquitous dragging tail. Virtually every dinosaur reconstruction from the late 19th to mid-20th century showed these animals with their massive tails dragging limply behind them like oversized lizards. This misconception persisted despite mounting evidence to the contrary, including fossil trackways that rarely showed tail drag marks. The anatomical reality, recognized fully only in the 1970s, is that dinosaur tails were dynamic structures held aloft by a complex system of muscles and tendons, serving critical functions in balance, locomotion, and, in some cases, defense. Theropod dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus rex used their tails as counterbalances to their heavy heads, while hadrosaurs and sauropods had tails that likely served as defense weapons against predators. The stiff, muscular tails of most dinosaurs were biomechanical marvels that bore little resemblance to the limp appendages depicted in early paleoart.

Anatomical Impossibilities: From Wrist Positions to Body Proportions

Early dinosaur reconstructions often contained anatomical configurations that would have been physically impossible for the living animals. A classic example is the “bunny hand” posture given to many theropod dinosaurs, with palms facing downward like a human’s. In reality, theropod wrists could not rotate this way; their hands naturally faced inward toward each other, an adaptation preserved in their avian descendants. Body proportions were frequently distorted as well, with many early reconstructions giving dinosaurs impossibly large heads, bloated bodies, or undersized limbs. The infamous “Brontosaurus” (now Apatosaurus) received the wrong head for decades after its discovery – a Camarasaurus skull placed on an Apatosaurus body – creating a chimeric creature that never existed. These errors stemmed not just from limited fossil material but also from simplistic assumptions about how animal bodies should be configured, often based more on artistic convention than biological reality.

The Swamp-Dwelling Dinosaur Myth

For decades, popular depictions showed large dinosaurs, particularly sauropods like Brontosaurus and Diplodocus, partially submerged in swamps and lakes. This “swamp-dwelling dinosaur” trope dominated mainstream illustrations from the early 1900s through the 1960s, with artists showing these massive creatures using water to support their allegedly unwieldy bulk. The hypothesis originated partly from the discovery of sauropod fossils in ancient river deposits and was reinforced by the assumption that such large animals couldn’t possibly support themselves on land. Paleontologist Alfred Sherwood Romer suggested that sauropods needed water buoyancy to counteract gravity’s effects on their massive frames. Modern biomechanical studies have thoroughly debunked this notion, demonstrating that sauropod anatomy was well-adapted for terrestrial life, with specialized weight-bearing limbs, air-filled vertebrae to reduce weight, and metabolic adaptations to support their enormous size on land.

The Cold-Blooded Assumption and Its Visual Impact

The assumption that dinosaurs were cold-blooded ectotherms like modern reptiles dramatically influenced how artists portrayed their appearance and behavior. Early paleoart typically showed dinosaurs as sluggish, slow-moving creatures with the dull, scaly skin of modern lizards. These depictions reflected the scientific consensus that persisted until the “Dinosaur Renaissance” of the 1960s and 1970s. Evidence now strongly suggests many dinosaurs had metabolic rates intermediate between modern reptiles and birds, with some lineages (particularly the ancestors of birds) developing full endothermy. This metabolic reassessment has revolutionized dinosaur art, with modern depictions showing more active, dynamic poses and behaviors. The cold-blooded assumption also affected how dinosaurs were colored in art, typically in muted greens and grays rather than the vibrant colors seen in many modern birds, which are, in fact, living dinosaurs. Recent fossil evidence of dinosaur pigmentation suggests some species had striking patterns and colors that would have appeared utterly foreign to early paleoartists.

The Missing Feathers: Dinosaurs Before the Avian Connection

Perhaps the most dramatic shift in dinosaur depictions concerns feathers, which were entirely absent from dinosaur reconstructions until the late 20th century. The discovery of Archaeopteryx in 1861 hinted at connections between dinosaurs and birds, but the full implications weren’t embraced until much later. Beginning with finds like the feathered Sinosauropteryx in 1996, a flood of remarkable fossils from China has revealed that many theropod dinosaurs possessed feathers or feather-like structures. This revelation has transformed our visual understanding of dinosaurs, with many species now accurately depicted with feathery coats ranging from simple filaments to complex flight feathers. The absence of feathers in early paleoart wasn’t just an omission of detail but reflected a fundamental misunderstanding of dinosaur biology and evolution. Many dinosaurs that were once depicted as scaly, reptilian creatures, including Velociraptor and its relatives, are now known to have been covered in elaborate feathers, making older depictions seem not just inaccurate but from an entirely different conceptual universe.

Cultural Influences on Dinosaur Depictions

Early dinosaur art wasn’t shaped by scientific understanding alone but also by the cultural context in which it was created. Victorian-era dinosaurs often reflected imperial attitudes, depicted as monstrous yet conquerable representatives of nature’s savage past. During the Cold War, dinosaurs became metaphors for evolutionary failure – huge, specialized creatures doomed to extinction due to their inability to adapt. These cultural projections influenced artistic choices in ways that now appear scientifically suspect. Dinosaurs were frequently portrayed with aggressive features and behaviors that spoke more to human anxieties than paleontological evidence. The color palettes chosen for dinosaur art also reflected cultural assumptions, with earthy tones suggesting primitivism and unnaturally bright colors reserved for the most exotic species. Even the environments in which dinosaurs were depicted – often barren, volcanic landscapes – owed more to cultural imaginings of a “prehistoric” world than to the actual ecosystems indicated by fossil evidence.

The Dinosaur Renaissance: Turning Point in Paleoart

A revolutionary shift in dinosaur depictions began in the late 1960s with what paleontologist Robert Bakker termed the “Dinosaur Renaissance.” This movement, spearheaded by Bakker, John Ostrom, and others, fundamentally reimagined dinosaurs as active, warm-blooded animals more similar to birds than to crocodiles. Ostrom’s discovery of Deinonychus, with its sickle-shaped claws and agile build, challenged prevailing views of dinosaurs as evolutionary failures. Artists like Gregory S. Paul pioneered a new aesthetic in dinosaur illustration, showing these animals in dynamic poses with anatomical precision previously unseen in paleoart. The Dinosaur Renaissance wasn’t just a scientific revolution but an artistic one, with dinosaurs suddenly depicted running, hunting in packs, and engaging in complex behaviors. This period marked the beginning of a more rigorous approach to paleontological reconstruction, with artists working more closely with scientists and paying greater attention to fossil evidence rather than relying on preconceived notions of how prehistoric animals should look.

Fragmentary Fossils and Creative Liberties

Many of the most amusing errors in early dinosaur art stemmed from the extremely fragmentary nature of the fossil evidence available to scientists and artists. When working with just a few vertebrae, a partial limb, or a fragmented skull, paleontologists had to make extensive extrapolations based on comparisons with better-known animals. These gaps in knowledge created opportunities for creative liberties that sometimes veered into the realm of fantasy. The first reconstruction of Iguanodon placed its thumb spike on its nose, creating a rhinoceros-like appearance entirely unrelated to the animal’s actual anatomy. Certain famous dinosaurs, like Spinosaurus, underwent dramatic revisions as more complete specimens were discovered; initial reconstructions as a typical large theropod were eventually replaced by the current understanding of a semi-aquatic predator with sail-like spines and paddle-like tail. These revisions remind us that paleoart represents hypotheses about appearance, not definitive portraits, and that even modern reconstructions may someday appear as amusingly incorrect as Victorian ones do to us now.

The Impact of Film and Popular Media

Popular media, particularly film, has played an outsized role in perpetuating outdated dinosaur imagery long after scientific understanding moved forward. The 1933 film “King Kong” featured dinosaurs based on Charles R. Knight’s influential but already somewhat outdated paintings. Disney’s “Fantasia” (1940) showcased dinosaurs that were more scientifically accurate for their time but quickly became outdated as paleontology advanced. The most influential modern depiction, “Jurassic Park” (1993), deliberately sacrificed scientific accuracy in some areas for dramatic effect, with its Velociraptors lacking feathers and Dilophosaurus sporting an entirely fictional neck frill and venom. These cinematic representations often freeze particular versions of dinosaurs in the public imagination, making it difficult for updated scientific understanding to displace popular misconceptions. Film producers have typically prioritized creating memorable, dramatic creatures over strict scientific fidelity, resulting in hybrid dinosaurs that combine scientific elements with purely artistic embellishments designed to enhance their entertainment value rather than their educational accuracy.

Modern Paleoart and Continuing Uncertainties

Contemporary paleoartists strive for greater scientific accuracy, working closely with paleontologists and incorporating the latest research into their reconstructions. Artists like Julius Csotonyi, James Gurney, and Emily Willoughby create dinosaur illustrations grounded in fossil evidence while acknowledging areas of uncertainty. Despite these advances, significant unknowns remain in dinosaur appearance. Soft tissue features like eyes, ears, lips, and certain aspects of coloration can only be inferred indirectly, leading to ongoing debates about how to reconstruct these elements accurately. The discovery of exceptionally preserved fossils with skin impressions, feather outlines, and even pigment-containing structures has dramatically improved our understanding of dinosaur appearance, but these specimens represent only a tiny fraction of known dinosaur species. Modern paleoartists typically indicate confidence levels in different aspects of their reconstructions, distinguishing between features directly supported by fossil evidence and those representing educated speculation. This more nuanced approach acknowledges that even our best modern depictions may contain errors that future discoveries will reveal.

Learning from Past Mistakes: The Value of Wrong Dinosaurs

The history of hilariously wrong dinosaur art provides more than just amusement; it offers valuable insights into the scientific process itself. Each generation of inaccurate dinosaurs represents the best understanding available at that time, illustrating how scientific knowledge evolves through continuous revision and refinement. These outdated reconstructions serve as snapshots of scientific thinking, revealing how prevailing theories shaped visual interpretations of fossil evidence. Early paleoart also demonstrates the dangers of excessive extrapolation from limited data and the power of cultural assumptions to influence supposedly objective scientific visualization. Modern paleontologists and paleoartists consciously study these past errors to avoid similar pitfalls in contemporary work. The progression from Victorian swamp-dwellers to modern feathered dinosaurs represents not just increasing accuracy but a methodological shift toward reconstructions more firmly grounded in evidence and less influenced by preconceptions. By understanding why early dinosaur art went so wrong, we gain appreciation for the complexities involved in reconstructing extinct life forms and develop healthy skepticism about even our current “definitive” depictions.

Conclusion

The evolution of dinosaur art from Victorian sculptures to modern digital reconstructions reflects not just advancing scientific knowledge but changing cultural perspectives on prehistoric life. What makes early dinosaur depictions so amusingly wrong to modern eyes is their combination of limited fossil evidence, misapplied analogies to modern animals, and cultural preconceptions about what ancient creatures “should” look like. Yet these seemingly ridiculous dinosaurs served an important purpose in their time, making paleontological discoveries accessible to the public and stimulating scientific and artistic imagination. Today’s more accurate dinosaurs—active, colorful, often feathered, and diverse in their adaptations—would be unrecognizable to early paleontologists, just as our current reconstructions will likely amuse future generations as new discoveries continue to refine our understanding of these fascinating animals.