The hunting behaviors of dinosaurs have captivated scientists and the public alike for generations. One of the most intriguing questions remains whether these magnificent prehistoric creatures were solitary hunters or worked together in coordinated packs like some modern predators. Recent paleontological discoveries have begun to shed light on this fascinating aspect of dinosaur behavior, revealing a complex picture that varies across different dinosaur species and periods. As we piece together evidence from fossils, trackways, and comparative studies with modern animals, a more nuanced understanding of dinosaur social structures and hunting strategies continues to emerge.

The Challenge of Interpreting Prehistoric Behavior

Determining how dinosaurs hunted presents unique challenges for paleontologists. Unlike bones that can fossilize, behaviors don’t leave direct physical evidence in the fossil record. Scientists must instead rely on indirect clues such as bone beds (mass accumulations of dinosaur remains), trackways (preserved footprints), bone damage patterns, and comparative studies with modern animals. These fragmentary pieces of evidence require careful interpretation, and conclusions about social hunting behaviors often remain tentative. The scientific understanding evolves with each discovery, making dinosaur behavioral paleontology one of the most dynamic areas of prehistoric research. Technological advances in biomechanics, computer modeling, and scanning technologies have recently allowed researchers to test hypotheses about dinosaur social behavior with increasing sophistication.

Evidence for Pack Hunting in Theropods

Some of the strongest evidence for coordinated hunting comes from certain theropod dinosaurs, the bipedal carnivorous group that includes famous predators like Velociraptor and Tyrannosaurus rex. The Deinonychus, made famous in the “Jurassic Park” franchise as “raptors,” has provided compelling evidence for pack hunting. Multiple Deinonychus specimens have been found alongside the remains of the much larger herbivore Tenontosaurus, suggesting they may have worked together to bring down prey too large for a single individual. The anatomical features of these dinosaurs, including their sickle-shaped claws, relatively large brains, and forward-facing eyes providing good depth perception, all support the possibility of coordinated hunting strategies. Trackways showing multiple individuals of the same species moving in the same direction at the same time further strengthen the case for social behavior in certain theropods.

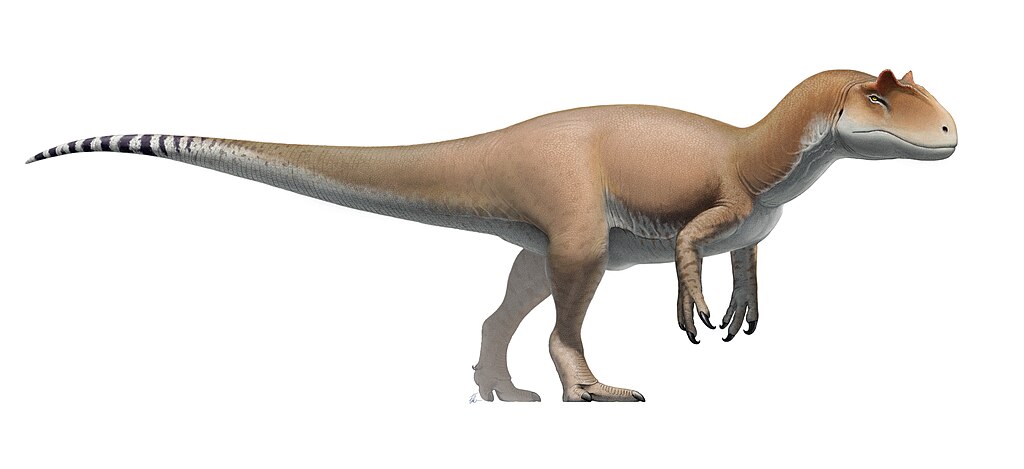

The Mapusaurus Mystery: Giant Pack Hunters?

One of the most intriguing cases for pack hunting comes from the discovery of multiple Mapusaurus individuals at a single site in Argentina. Mapusaurus, a relative of Giganotosaurus and one of the largest carnivorous dinosaurs ever discovered, reached lengths of up to 41 feet. The bone bed contained at least seven individuals of varying ages, suggesting these massive predators may have lived and possibly hunted in family groups. This discovery is particularly significant because it challenges the assumption that the largest predatory dinosaurs were necessarily solitary. Pack hunting would have given these giants a strategic advantage when targeting the massive titanosaur sauropods that shared their environment. The concentration of multiple large predators in one location is difficult to explain through random fossilization events and strongly suggests some form of social grouping.

Tyrannosaurus Rex: Social Predator or Solitary Hunter?

The hunting behavior of Tyrannosaurus rex, perhaps the most iconic predatory dinosaur, remains highly debated among paleontologists. Traditionally portrayed as a solitary hunter, recent evidence has called this assumption into question. The discovery of multiple T. rex specimens nearby at sites like the “Mega-Site” in Montana suggests these animals may have at least tolerated each other’s presence. Their massive size and power would have made T. rex formidable hunters even on their own, capable of taking down large hadrosaurs and ceratopsians. However, their relatively small arms and slow running speed might have made cooperative hunting advantageous when pursuing faster prey. The debate continues with some researchers suggesting T. rex may have exhibited different social behaviors at different life stages, potentially hunting in loose groups as juveniles before becoming more solitary as adults.

The Albertosaurus Bone Bed: Evidence of Tyrannosaur Sociality

One of the most compelling pieces of evidence for social behavior in tyrannosaurs comes from an extraordinary bone bed in Alberta, Canada. This site contains the remains of at least 12 Albertosaurus individuals of various ages, from juveniles to adults, all preserved together. The discovery strongly suggests these tyrannosaurs were traveling together at the time of their death, possibly due to a catastrophic flooding event. This mixed-age group structure mirrors the family groups seen in modern social predators like wolves. While this evidence doesn’t definitively prove cooperative hunting, it does indicate some form of social grouping that could have facilitated coordinated predatory behavior. The presence of both young and mature individuals suggests potential knowledge transfer between generations, another hallmark of social predators in modern ecosystems.

Utahraptor: The Ultimate Pack Hunter?

Utahraptor, the largest known dromaeosaurid or “raptor” dinosaur, provides some of the most compelling evidence for pack hunting among dinosaurs. A remarkable discovery in Utah revealed a group of at least six Utahraptors of different ages preserved together, suggesting a family group. These 23-foot-long predators possessed all the anatomical adaptations that would make coordinated hunting effective, including grasping hands, sharp teeth, and the infamous enlarged sickle claw on each foot. The preservation of multiple individuals together indicates these animals lived in social groups, and their physical adaptations suggest they were capable of taking down prey much larger than themselves through coordinated attacks. The variation in sizes within the group suggests different individuals might have played different roles during hunts, similar to how modern wolf packs operate with distinct hunting strategies for different pack members.

Solitary Hunters: The Case for Individual Predation

Despite growing evidence for social behavior in some dinosaur species, many predatory dinosaurs likely hunted alone. This solitary strategy makes ecological sense for many medium-sized predators that target prey they could handle individually. Modern analogies can be found in crocodilians, komodo dragons, and most large cat species, which primarily hunt alone despite occasional social interactions. Fossil evidence for some theropod species consistently shows isolated individuals rather than groups, supporting the solitary hunter hypothesis for these dinosaurs. Energy efficiency also favors solitary hunting when prey is small enough to be captured by a single predator, as the hunter doesn’t have to share the spoils. The diverse ecological niches occupied by different dinosaur species likely promoted a variety of hunting strategies, with solitary hunting being advantageous in many contexts.

Allosaurus: Opportunistic Pack Hunters or Aggressive Loners?

Allosaurus, a large Jurassic predator, presents an interesting case study in dinosaur hunting behavior. The famous Cleveland-Lloyd Quarry in Utah contains the remains of dozens of Allosaurus individuals, initially suggesting potential social behavior. However, closer examination indicates these specimens likely accumulated over time as individuals were attracted to dying herbivores trapped in a predator trap, similar to the La Brea Tar Pits. Evidence of bite marks on Allosaurus bones from other Allosaurus individuals suggests these dinosaurs may have been cannibalistic and highly territorial rather than cooperative. Yet other Allosaurus sites show multiple individuals that appear to have died together, potentially indicating context-dependent social behavior. This complex picture suggests Allosaurus might have exhibited flexible social strategies, perhaps gathering opportunistically at large carcasses but otherwise hunting alone or in temporary associations.

Modern Analogs: What Living Animals Tell Us About Dinosaur Behavior

The study of modern animals provides crucial context for interpreting dinosaur social behavior. Komodo dragons, the largest living reptiles, hunt primarily as solitary ambush predators but will tolerate others at large carcasses in a behavior known as “communal feeding.” Crocodilians occasionally engage in cooperative fishing behaviors despite being largely solitary. Birds, the direct descendants of theropod dinosaurs, display an enormous range of social structures, from strictly solitary hunters to highly coordinated pack hunters like Harris’s hawks. Large mammalian carnivores also show varied social strategies, with lions hunting in prides while tigers remain solitary. These diverse modern examples suggest dinosaurs likely exhibited a similar spectrum of social hunting behaviors rather than following a single pattern. The brain-to-body size ratios and sensory adaptations of different dinosaur species can provide clues about their cognitive capabilities for social coordination.

Trackway Evidence: Footprints Tell a Social Story

Fossilized trackways provide some of the most direct evidence of dinosaur social behavior. Multiple parallel trackways of the same species moving in the same direction at the same time strongly suggest group movement, if not coordinated hunting. A remarkable example comes from La Rioja, Spain, where scientists discovered trackways of at least six carnivorous dinosaurs walking in the same direction at the same time. Similar evidence has been found for ornithomimids (“ostrich mimics”) in Colorado, suggesting these omnivorous theropods traveled in groups. Trackways also provide information about spacing between individuals, walking speed, and age composition of groups based on footprint size. The preservation of multiple trackways representing the same moment in time offers a rare glimpse into dinosaur social dynamics that bone fossils alone cannot provide.

The Evolutionary Advantages of Pack Hunting

Pack hunting offers several evolutionary advantages that could explain its development in certain dinosaur lineages. Coordinated hunting allows predators to target prey much larger than themselves, expanding the range of available food sources. For example, a pack of Deinonychus could potentially take down the much larger Tenontosaurus, while individual hunters would be limited to smaller prey. Pack hunting also increases hunting success rates through strategies like ambushing or herding prey. Young or inexperienced hunters can learn from more experienced group members, accelerating skill development. Protection from other predators or competing groups represents another significant advantage of social living. These benefits must outweigh the costs of sharing food and increased competition for resources within the group, suggesting pack hunting would evolve only under specific ecological conditions where the advantages were substantial.

The Role of Intelligence in Dinosaur Social Hunting

Effective pack hunting requires a level of cognitive ability that allows for coordination, communication, and potentially role specialization during hunts. Brain endocasts from theropod dinosaurs provide insights into their neural capabilities. Notably, dromaeosaurids like Velociraptor had relatively large brains for their body size, with expanded cerebral hemispheres that may have supported more complex social behaviors. Troodontids, close relatives of dromaeosaurids, had some of the highest brain-to-body ratios among dinosaurs, potentially supporting sophisticated hunting strategies. The enlarged optic lobes in many theropods suggest excellent vision, useful for coordinating with pack members during hunts. While dinosaur intelligence likely didn’t match that of modern mammals, certain lineages appear to have possessed sufficient cognitive capacity for some level of coordinated hunting behavior. The evolution of larger brains in some theropod lineages parallels similar trends in social mammalian predators, suggesting convergent evolution toward cognitive abilities that support group hunting.

Implications for Dinosaur Ecology and Evolution

The hunting strategies of dinosaurs had profound implications for prehistoric ecosystems. Pack hunting predators exert different selective pressures on prey populations compared to solitary hunters, potentially driving the evolution of defensive adaptations in herbivorous dinosaurs. The horns and frills of ceratopsians, the armor of ankylosaurs, and the herding behavior suggested by hadrosaur fossils may all represent responses to predation pressure. Understanding dinosaur hunting behavior also provides insights into dinosaur social structures beyond predation, including potential family groups and herding behaviors. The evolution of pack hunting in certain dinosaur lineages may have contributed to their success, allowing them to exploit ecological niches unavailable to solitary predators. These social innovations potentially represent important evolutionary experiments that preceded the complex social behaviors seen in modern birds, the living descendants of theropod dinosaurs.

Conclusion

The question of whether dinosaurs hunted in packs or alone doesn’t have a single answer. The evidence points to a diverse range of hunting strategies across different dinosaur species, reflecting the incredible ecological diversity of these animals during their 165-million-year reign. Some species, particularly certain dromaeosaurids and potentially some larger theropods, show compelling evidence of social behavior that may have included coordinated hunting. Others likely remained solitary predators throughout their lives. Many probably exhibited flexible social behaviors, similar to modern predators that adapt their strategies to specific circumstances. As paleontological techniques continue to advance and new fossils are discovered, our understanding of dinosaur social behavior will undoubtedly continue to evolve, adding new chapters to the fascinating story of how these remarkable animals lived and hunted.