Dinosaur nesting sites represent one of paleontology’s most remarkable windows into prehistoric life. Unlike isolated fossils that capture only a moment in an animal’s existence, nesting sites reveal intimate details about dinosaur reproductive behaviors, parental care, and social structures. These rare discoveries allow scientists to piece together how dinosaurs raised their young, organized their communities, and adapted their reproductive strategies to different environments. From the massive communal nesting grounds of Argentina to the carefully constructed nests found in Mongolia’s Gobi Desert, these sites tell a fascinating story about dinosaur life that continues to evolve as discoveries emerge. The study of dinosaur nests has revolutionized our understanding of these ancient creatures, showing they were far more complex and sophisticated in their behaviors than once believed.

The Evolution of Dinosaur Nesting Research

The scientific understanding of dinosaur reproduction has undergone a dramatic transformation since the first dinosaur eggs were scientifically described in the late 19th century. Early discoveries were often misidentified or misunderstood, with some eggs initially thought to belong to large birds or even other reptiles. The watershed moment came in 1923 when Roy Chapman Andrews and his American Museum of Natural History expedition discovered dinosaur eggs in Mongolia’s Gobi Desert, definitively proving that dinosaurs laid eggs rather than giving live birth. Subsequent decades saw sporadic discoveries, but it wasn’t until the 1970s and 1980s that nesting sites began receiving rigorous scientific attention. Modern research now incorporates advanced technologies like CT scanning, chemical analysis, and microscopic examination of eggshell structures to extract maximum information from these precious sites. This evolutionary journey in research methodology has transformed dinosaur nesting sites from curiosities to critical scientific resources that reveal intimate details about dinosaur biology.

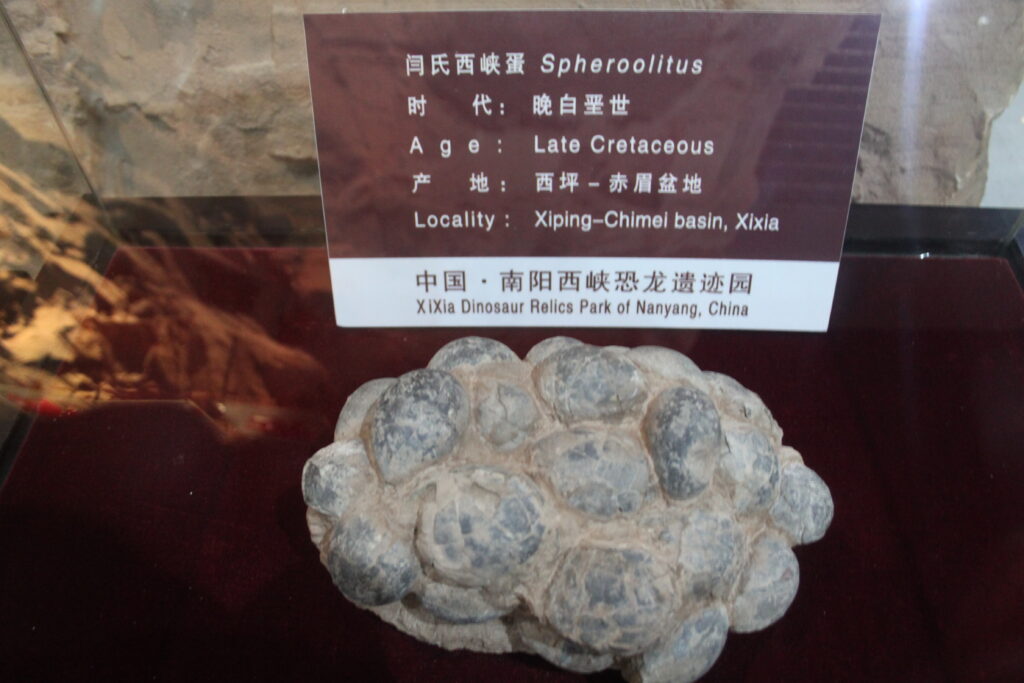

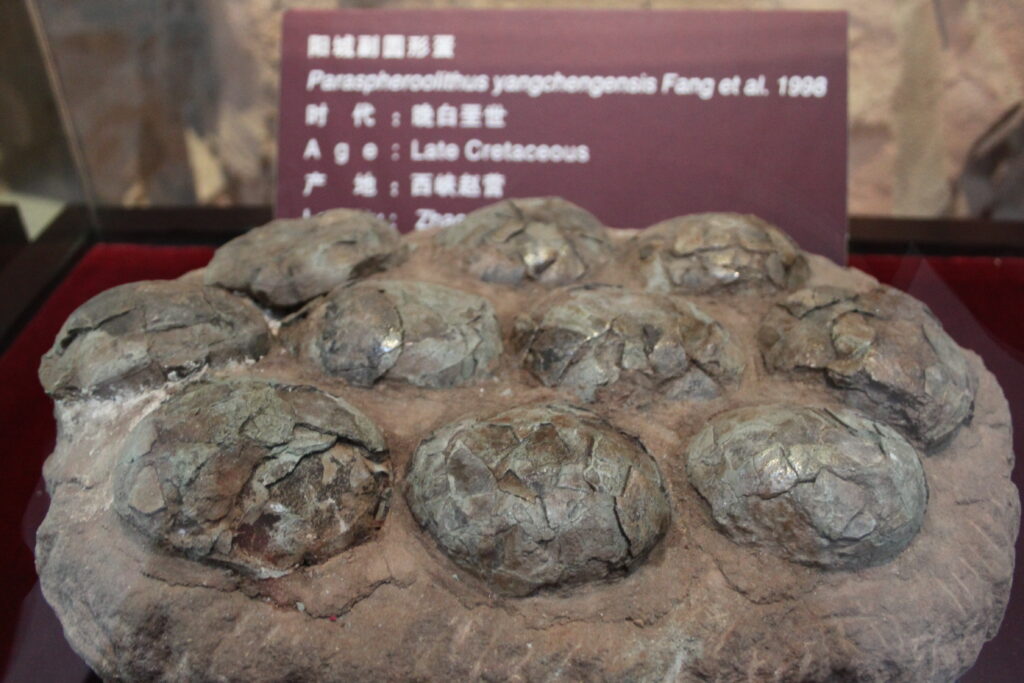

Egg Morphology and What It Reveals

Dinosaur eggs display remarkable diversity in size, shape, and shell structure, with each variation providing clues about their creators. The massive, nearly spherical eggs of sauropods could reach up to 20 centimeters in diameter, reflecting the enormous size of the adults. Theropod eggs, by contrast, tend to be more elongated and asymmetrical, similar to modern bird eggs, highlighting the evolutionary connection between these dinosaurs and today’s avian species. Microstructural analysis of eggshells reveals distinct patterns that help paleontologists identify which dinosaur species laid particular eggs, even when embryonic remains are absent. The porosity of eggshells offers insights into nesting environments—highly porous shells suggest buried nests where gas exchange could occur through surrounding soil, while less porous shells indicate open nests where eggs were exposed to air. Shell thickness variations also provide clues about incubation strategies, with thicker shells generally better suited to protect eggs in open nesting situations. These morphological features collectively create a detailed picture of reproductive adaptations across different dinosaur lineages.

Nest Architecture and Construction Behaviors

Dinosaur nest construction reveals sophisticated behaviors that varied widely across different species. Hadrosaurs (duck-billed dinosaurs) often created large bowl-shaped depressions in the ground, arranging their eggs in circular patterns that suggest the adults may have sat directly on the clutch. Theropods frequently constructed more elaborate nests with raised rims of mud or vegetation, arranging eggs in concentric circles with remarkable precision. Some of the most complex nest structures appear in oviraptorid dinosaurs, which built nests remarkably similar to modern ground-nesting birds, with carefully arranged eggs partially buried in sediment. Evidence from the Gobi Desert shows some species created nest mounds from available vegetation, while others dug shallow pits in riverbeds. Perhaps most impressive are the indications of nest maintenance, with some sites showing signs that dinosaurs periodically rotated or rearranged eggs during incubation. These construction behaviors demonstrate purposeful, species-specific nest-building strategies that went far beyond simple egg deposition, suggesting cognitive complexity and advanced parental instincts among many dinosaur species.

Colonial Nesting and Social Dynamics

Many dinosaur species appear to have nested in colonies, providing fascinating insights into their social structures and communal behaviors. The most spectacular evidence comes from sites like Auca Mahuevo in Argentina, where hundreds of sauropod nests have been discovered nearby, creating what amounts to a massive prehistoric nursery. Similar colonial nesting grounds have been found for hadrosaurs in Montana and Alberta, suggesting this behavior was widespread across different dinosaur families. These colonies likely served multiple adaptive purposes, from providing collective defense against egg predators to enabling efficient use of suitable nesting terrain. The spatial organization within these colonies reveals sophisticated social dynamics, with nests often placed at remarkably consistent distances from each other, suggesting that territorial boundaries were maintained. In some sites, evidence indicates these colonies were used repeatedly over many seasons, with dinosaurs returning to the same general areas to reproduce year after year. The presence of eggs and juveniles within some colonies further suggests these sites functioned as complex communities where multiple generations interacted, challenging earlier views of dinosaurs as solitary or simplistic in their social behaviors.

Parental Care Evidence in the Fossil Record

Perhaps the most emotionally resonant discoveries from dinosaur nesting sites are those that illuminate parental care behaviors. The most famous example is the “fighting dinosaurs” specimen from Mongolia, showing an Oviraptor positioned directly over a nest in a protective posture, apparently having perished while defending its eggs from a predatory Velociraptor. Multiple additional Oviraptor specimens have been found in brooding positions atop nests, with their limbs arranged around the eggs in patterns virtually identical to modern nesting birds. Microscopic analysis of eggshells at some sites reveals thinning patterns consistent with embryos approaching the hatching stage, suggesting adults remained with nests until the young emerged. At Egg Mountain in Montana, researchers have found juvenile Maiasaura specimens still within nesting grounds but too large to have just hatched, indicating extended post-hatching parental care where adults continued providing protection and possibly food to growing offspring. Trackway evidence occasionally preserved near nesting sites shows both adult and juvenile footprints together, further supporting the hypothesis that many dinosaur species invested significantly in raising their young. These discoveries collectively paint a picture of dinosaurs as attentive parents rather than the cold, reptilian abandoners they were once assumed to be.

Temperature Regulation and Incubation Strategies

Dinosaur nesting sites provide critical evidence about how these animals regulated egg temperatures during incubation, a key aspect of reproductive biology. Oxygen isotope analysis of some eggshells indicates temperature ranges during development, revealing that many dinosaur species maintained remarkably consistent incubation temperatures. Some nests show evidence of partial burial in soil or rotting vegetation, which would have generated heat through decomposition—a strategy still used by modern crocodilians and some megapode birds. Other nests, particularly those of theropods closely related to birds, show structural arrangements suggesting direct body contact during incubation, where adults transferred body heat to the eggs. The placement of nests often appears strategic for temperature regulation, with some species preferring sun-exposed locations while others select areas with more moderate temperature fluctuations. Particularly fascinating are nests found in geothermally active areas, suggesting some dinosaurs deliberately exploited natural heat sources to incubate their eggs—a behavior observed in present-day megapode birds that use volcanic warmth for incubation. These varied approaches to temperature management reflect sophisticated adaptations that helped dinosaurs successfully reproduce across diverse environments and climatic conditions.

Embryonic Development and Growth Patterns

Exceptionally preserved dinosaur eggs containing embryonic remains provide unprecedented glimpses into dinosaur development before hatching. CT scanning technology has revolutionized this field, allowing researchers to examine embryos within eggs without damaging the specimens. These scans reveal embryonic postures, skeletal development sequences, and even organ positions in some cases. Studies of embryonic bone microstructure show rapid growth rates even before hatching, with some species developing the bone structures necessary for walking within the egg. Particularly revealing are comparisons between embryonic dinosaurs and modern birds and crocodilians, which show theropod dinosaurs followed developmental pathways more similar to birds than to other reptiles. Some exceptionally preserved specimens even retain evidence of embryonic “egg teeth”—specialized structures used to break through the shell during hatching, similar to those in modern birds. Growth lines in embryonic bones also provide insights into incubation periods, suggesting some larger dinosaur species may have had remarkably long incubation times of six months or more, considerably longer than the maximum two-month incubation period observed in modern birds. These embryonic studies bridge critical knowledge gaps between adult dinosaur biology and reproductive strategies.

Geographic Distribution and Environmental Adaptations

Dinosaur nesting sites have been discovered on every continent except Antarctica, revealing how these animals adapted their reproductive strategies to diverse environments worldwide. Nesting grounds in ancient tropical settings like those found in India show distinctive adaptations to high humidity and seasonal monsoons, with evidence suggesting some species timed their reproduction to avoid seasonal flooding. In more arid environments like the Gobi Desert, nests often show adaptations for moisture conservation, including specialized eggshell structures that balance gas exchange with water retention. High-latitude nesting sites discovered in Alaska and Australia provide particularly interesting insights, as dinosaurs breeding in these regions would have faced seasonal challenges, including periods of darkness and cooler temperatures. Some sites show evidence of migration, with certain species traveling to particular nesting grounds seasonally—a behavior similar to many modern birds. The consistency of nesting strategies within species across different geographic locations suggests genetically programmed behaviors, while variations between populations indicate the capacity for environmental adaptation. This global distribution of nesting sites challenges the outdated notion of dinosaurs as primarily tropical animals, demonstrating their remarkable adaptability to diverse climatic conditions.

The Bird-Dinosaur Connection Through Nesting Behaviors

Perhaps nowhere is the evolutionary link between dinosaurs and birds more evident than in their reproductive behaviors. Oviraptorids and other maniraptoran theropods constructed nests strikingly similar to those of modern ground-nesting birds, arranged their eggs in similar patterns, and adopted nearly identical brooding postures over their clutches. The asymmetrical egg shape seen in many theropod dinosaurs is virtually identical to modern bird eggs, an adaptation that keeps the developing embryo properly positioned for efficient gas exchange and successful hatching. Microscopic analysis of eggshell structures reveals the distinctive two-layered pattern characteristic of birds, appearing first in theropod dinosaurs, representing a key evolutionary innovation. Even clutch sizes show evolutionary trends, with the number of eggs per nest generally decreasing along the lineage leading to birds, while parental investment in each offspring increased. Egg color evidence is rare but significant—recent chemical analysis of oviraptorid eggs has detected traces of the same pigments that color modern bird eggs, suggesting some dinosaurs laid colored or patterned eggs. These nesting similarities provide some of the strongest behavioral evidence for the now well-established theory that birds are, in fact, living dinosaurs that retained many reproductive strategies from their larger ancestors.

Nest Predation and Defensive Strategies

Dinosaur nests represented vulnerable targets for Mesozoic predators, and nesting sites reveal fascinating evidence of the evolutionary arms race between egg-layers and egg-eaters. Crushed and punctured eggs at some sites bear tooth marks matching known predators, while others show signs of careful excavation by smaller creatures seeking an easy meal. In response to these threats, many dinosaur species developed sophisticated defensive strategies. Colonial nesting provided safety in numbers, with multiple adults potentially available to defend against threats. Some nesting grounds show evidence of adult dinosaurs positioning themselves around the colony’s perimeter, creating a defensive formation. Egg burial served not only for incubation purposes but also concealed eggs from visual predators. The tough, calcified shells of many dinosaur eggs represented a physical barrier against small predators, while some species produced eggs with unusual surface textures or chemical compositions that may have deterred certain predators. Perhaps most ingeniously, some dinosaurs appear to have selected nesting locations specifically for their defensive advantages—on islands, steep slopes, or areas with limited predator access. These diverse anti-predation strategies reflect millions of years of coevolution between dinosaur parents and the many creatures that viewed their eggs as potential meals.

Modern Research Technologies Revolutionizing Nest Studies

Twenty-first-century technologies have transformed the study of dinosaur nesting sites, extracting unprecedented details from these ancient nurseries. Advanced CT scanning can now reveal embryonic remains within eggs without breaking them open, providing three-dimensional models of developing dinosaurs in their pre-hatching state. Scanning electron microscopy allows researchers to examine eggshell microstructures at magnifications that reveal cellular-level details about shell formation and function. Geochemical analyses using mass spectrometry can detect trace elements and isotope ratios in eggshells that indicate the mother dinosaur’s diet, migration patterns, and even stress levels during egg formation. Ancient DNA extraction techniques, while still extremely challenging with dinosaur material, have occasionally yielded genetic fragments from exceptionally preserved eggs, offering tantalizing glimpses of dinosaur genomes. Ground-penetrating radar and other remote sensing technologies now allow paleontologists to locate and map potential nesting sites without destructive excavation, preserving sites for targeted scientific sampling. Computer modeling based on egg arrangements and nest structures can simulate incubation conditions, predicting how heat would have transferred through different nest designs. These technological advances continue accelerating our understanding of dinosaur reproduction, answering questions that would have seemed impossible to address just decades ago.

Case Study: The Oviraptor’s Reputation Rehabilitation

The story of Oviraptor represents one of the most dramatic reputation reversals in paleontology, illustrating how nesting sites can fundamentally change our understanding of dinosaur behavior. When first discovered in Mongolia in 1923, this dinosaur was found near a nest of what were thought to be Protoceratops eggs, leading to its scientific name Oviraptor philoceratops—literally “egg thief, lover of ceratopsians.” For decades, this dinosaur was portrayed as a notorious nest raider, stealing and consuming other dinosaurs’ eggs. This interpretation was dramatically overturned in the 1990s when identical eggs were found containing embryonic Oviraptor remains, proving they were the animal’s eggs rather than stolen ones. Further discoveries revealed Oviraptor adults in brooding positions directly atop nests, their limbs splayed out in precisely the same posture modern birds use when incubating eggs. The original specimen, far from being caught in the act of theft, had likely died while protecting its own nest, possibly from the sandstorm that preserved the fossils. This complete reinterpretation transformed Oviraptor from villain to devoted parent, highlighting how nesting evidence can fundamentally reshape our understanding of dinosaur behavior and provide an emotional connection to these ancient creatures.

Future Directions in Dinosaur Nesting Research

The study of dinosaur nesting sites continues evolving rapidly, with several promising research frontiers likely to yield significant discoveries in the coming years. Expanded global exploration efforts are focusing on undersampled regions like Africa and Southeast Asia, where distinct climatic conditions may have produced unique nesting adaptations. Molecular paleontology techniques show increasing potential for extracting original organic compounds from exceptionally preserved eggs, potentially revealing eggshell proteins and pigments that could clarify evolutionary relationships and egg coloration patterns. Time-series analysis of growth lines in embryonic bones may soon provide precise incubation duration estimates for various dinosaur species, clarifying a critical aspect of reproductive investment. Comparative studies integrating dinosaur nesting data with the full range of modern bird and reptile reproductive strategies are creating more nuanced evolutionary models of how parental care developed. Environmental reconstruction around nesting sites is becoming increasingly sophisticated, potentially revealing how dinosaurs selected optimal nesting locations based on microclimate, vegetation, and predator density. Perhaps most excitingly, ongoing fieldwork continues uncovering completely new nesting sites annually, with each discovery holding potential to overturn existing theories and provide fresh insights into how these magnificent animals reproduce and rraisetheir young.

Conclusion

Dinosaur nesting sites represent paleontological treasures that continue transforming our understanding of these fascinating creatures. From the sophisticated nest construction and colonial behaviors to the touching evidence of parental devotion, these sites reveal dinosaurs as complex animals with reproductive strategies often more similar to birds than to modern reptiles. The eggs, nests, and embryos preserved across millions of years tell stories of evolutionary adaptation, parental investment, and survival strategies that resonate across time. As research technologies advance and more sites are discovered worldwide, our picture of dinosaur reproduction grows increasingly detailed and nuanced. Perhaps most significantly, these nesting sites create an emotional connection to dinosaurs not as movie monsters but as real animals that faced the universal challenges of reproduction and offspring protection. In their nesting behaviors, we see not just prehistoric creatures but parents—a perspective that fundamentally humanizes our view of these remarkable animals and bridges the ancient past with our own experiences of care, risk, and survival.