In the realm of paleontology, few discoveries spark as much scientific debate as the potential preservation of soft tissues. While bones and teeth regularly survive the fossilization process, delicate organic structures like brains typically decompose long before mineralization can occur. Yet in 2016, scientists announced what they believed to be the first preserved dinosaur brain tissue ever found—a brownish specimen discovered in Sussex, England. This remarkable claim immediately divided the scientific community, with some researchers hailing it as a revolutionary find and others expressing profound skepticism. Years later, the debate continues to rage about whether this fossil truly represents preserved brain tissue from a dinosaur that lived approximately 133 million years ago, or if it’s something else entirely.

The Controversial Discovery in Sussex

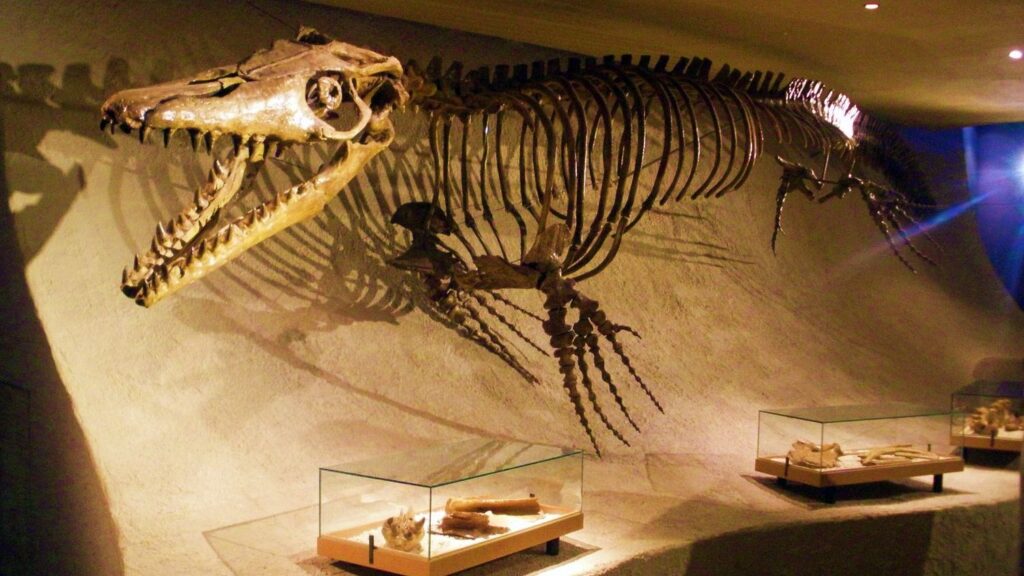

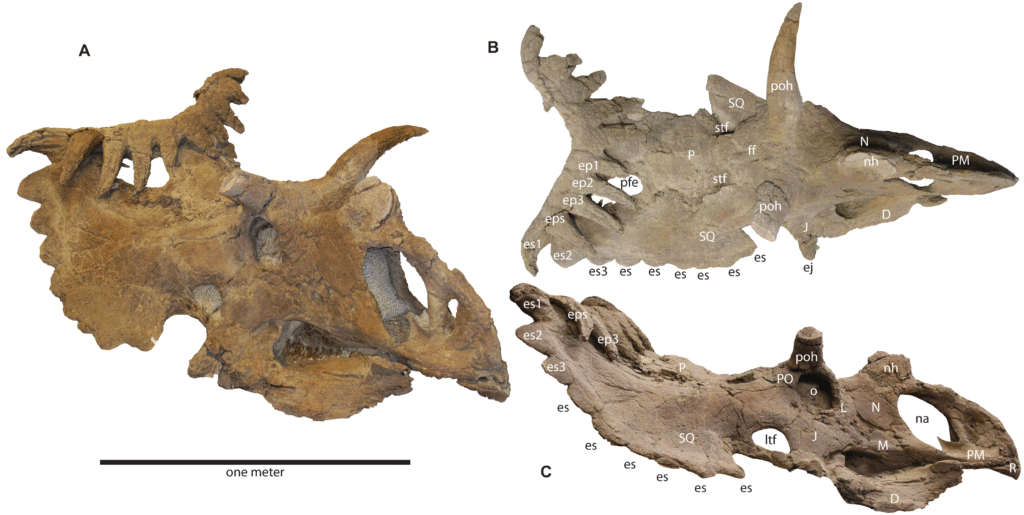

The story begins with an amateur fossil collector who stumbled upon an unusual brownish pebble-like object on a beach in Sussex, England in 2004. This unassuming specimen sat in a collection for years before eventually making its way to scientists at the University of Cambridge. Initial examination revealed surprising structural details that resembled brain tissue, complete with what appeared to be meninges (protective brain coverings) and cortical tissues with blood vessels. The fossil was associated with a dinosaur from the Iguanodon group, a large herbivorous species that roamed what is now England during the Early Cretaceous period. What made this find particularly extraordinary was that brain tissue is among the fastest decomposing materials in any organism, typically breaking down within days after death—making its preservation through millions of years seem almost miraculous.

The Preservation Paradox

The central question that continues to divide paleontologists is straightforward yet profound: how could brain tissue possibly survive for 133 million years? The researchers who support the brain tissue interpretation propose an exceptional sequence of events that might have allowed for such preservation. They suggest the dinosaur’s head likely fell into a highly acidic, low-oxygen body of water immediately after death. This environment would have pickled the brain tissue, essentially beginning a chemical preservation process before decomposition could fully take hold. Furthermore, they propose that minerals gradually replaced the organic structures while maintaining their original arrangement—a process called mineralization. This specific combination of factors would need to occur rapidly and in perfect sequence, which skeptics argue makes the brain tissue interpretation highly improbable regardless of how compelling the visual evidence might appear.

Microscopic Evidence: What the Scientists Saw

When examined under powerful microscopes, the fossilized specimen revealed structures that bore striking resemblance to brain tissues found in modern reptiles and birds (the closest living relatives to dinosaurs). Researchers identified what appeared to be meninges—the protective membranes that cover vertebrate brains—as well as cortical tissues with recognizable blood vessel patterns. Using sophisticated techniques like scanning electron microscopy, scientists detected collagen fibers and structures resembling capillaries within the mineralized tissue. Perhaps most compelling was the identification of minuscule tubular structures that resembled neural tissues arranged in patterns consistent with brain matter. These microscopic features provided the strongest evidence for the brain interpretation, as such complex biological structures would be difficult to explain through non-biological mineralization processes alone.

The Case for Bacterial Biofilms

Skeptics have proposed alternative explanations for the mysterious structures observed in the Sussex fossil. Among the most compelling counter-theories is that the supposed brain tissue actually represents bacterial biofilms—complex communities of microorganisms that can create organized structures as they colonize a surface. When dinosaur remains settled into sediment, bacteria could have colonized the skull cavity where the brain once existed. Over time, these bacterial colonies might have created layered structures that vaguely resemble neural tissues. Proponents of this theory point out that bacterial biofilms are known to create remarkably organized structures that can mimic biological tissues, and these microorganisms can actively participate in the mineralization process. Additionally, biofilms would be far more likely to undergo fossilization than actual brain matter, making this explanation more consistent with our understanding of taphonomy (the study of how organisms decay and become fossilized).

Comparing with Modern Brain Preservation

Scientists studying the Sussex specimen have compared it with known examples of preserved brain tissue from more recent contexts to evaluate its plausibility. Modern medical practices can preserve brain tissue through chemical fixation using formaldehyde and other substances, but even these carefully preserved specimens show significant degradation over decades, let alone millions of years. In rare archaeological finds, human brain tissue has been found preserved in anaerobic (oxygen-free) environments such as bogs or permafrost, but these specimens are thousands—not millions—of years old. The oldest confirmed preserved brain tissue comes from a 2,600-year-old human skull found in a pit in York, England, where unique soil chemistry created preservation conditions. The tremendous gap between these examples (measured in thousands of years) and the purported dinosaur brain (133 million years) highlights why many scientists remain skeptical about the dinosaur brain interpretation.

Chemical Analysis of the Fossil

Advanced chemical analyses have been conducted on the Sussex specimen to determine its composition and potentially resolve the debate. Researchers have used techniques such as mass spectrometry and infrared spectroscopy to identify the chemical compounds present in the fossil. These tests revealed the presence of carbonaceous material that could potentially represent degraded organic compounds from original brain tissue. Some analyses detected carbon and nitrogen ratios consistent with biological material, which supporters cite as evidence for preserved organic matter. However, skeptics note that similar chemical signatures can result from bacterial activity or geological processes occurring long after the dinosaur’s death. Additionally, the presence of iron compounds in the fossil suggests the preservation might have involved a process called pyritization, where iron sulfides replace organic materials—a process that could preserve structural details without necessarily requiring the survival of actual brain tissue.

The Rarity Factor: Why Just One Brain?

One of the strongest arguments against the brain tissue interpretation is the profound uniqueness of the find. Despite over 150 years of intensive dinosaur fossil collection worldwide, this remains the only purported example of preserved brain tissue. If the extraordinary preservation conditions proposed by the pro-brain researchers were possible, we might expect to find more examples among the thousands of dinosaur skulls discovered globally. The singular nature of this find raises legitimate questions about whether it represents a once-in-a-paleontological-lifetime preservation event or whether the interpretation itself may be flawed. Some scientists suggest that if brain preservation were possible under certain conditions, we should expect clusters of similar finds in regions that experienced those specific conditions, rather than a single isolated example from Sussex.

The Technical Challenges of Ancient Tissue Identification

Identifying ancient soft tissues presents enormous technical challenges that contribute to the ongoing debate. Fossilization typically involves the replacement of original biological materials with minerals, making it difficult to distinguish between actual preserved tissues and mineralized replicas that merely retained the shape of long-decomposed structures. Scientists must rely on comparative anatomy with modern analogues (like reptile and bird brains) to interpret structures that may have changed significantly during fossilization. Furthermore, contamination poses a serious problem—modern bacteria, fungi, or other microorganisms can infiltrate fossils during excavation or storage, creating misleading signals in chemical and structural analyses. These technical challenges have led many paleontologists to adopt extremely conservative standards for claims of soft tissue preservation, particularly for specimens of such extraordinary age.

The Expert Divide: Scientific Opinions

The scientific community remains deeply divided over the interpretation of the Sussex specimen. Paleontologists specializing in dinosaur anatomy tend to be more receptive to the brain tissue interpretation, noting the striking similarities between the fossil structures and known brain anatomy in related living species. Conversely, taphonomists—scientists who study fossilization processes—generally express greater skepticism, emphasizing the extreme improbability of brain preservation over such vast timescales. This division of expert opinion largely stems from different scientific perspectives; anatomists focus on what the structures look like, while taphonomists concentrate on the physical and chemical processes that could realistically produce such structures. Some researchers have taken middle-ground positions, suggesting the fossil might represent mineralized remnants of meninges (the tough outer brain coverings) rather than actual neural tissue, which would be somewhat more plausible from a preservation standpoint.

Implications for Dinosaur Neurology

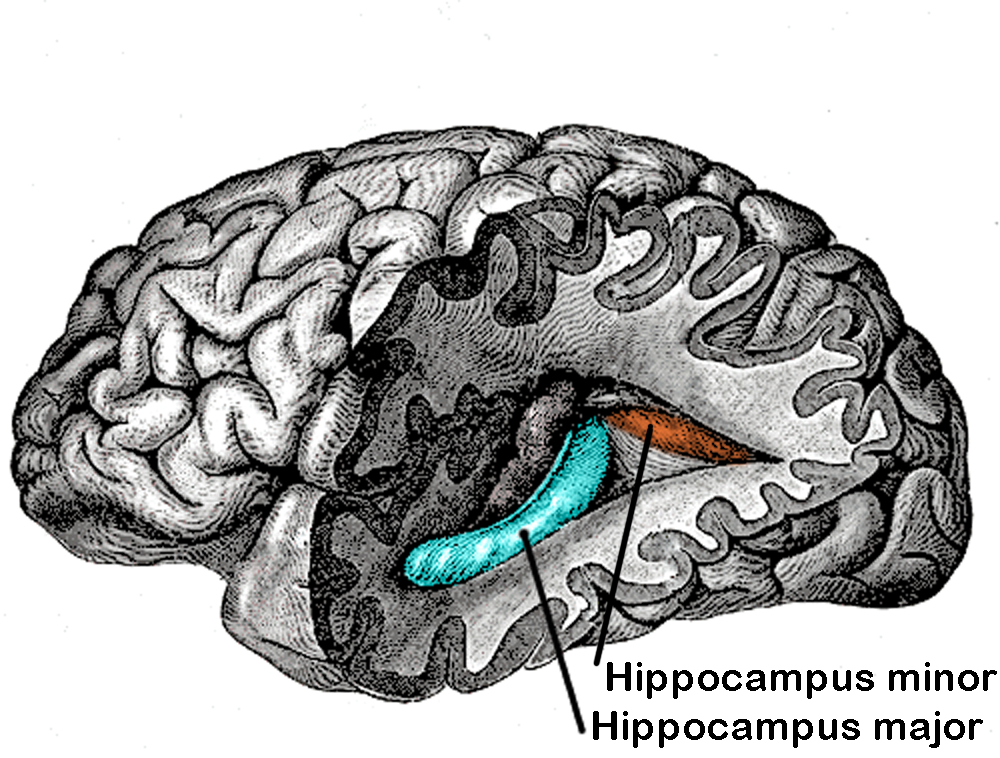

If the Sussex specimen truly represents preserved brain tissue, its implications for our understanding of dinosaur neurology would be profound. The fossil appears to show a brain that pressed against the skull cavity more closely than scientists previously believed for dinosaurs of this type. This would suggest a larger brain-to-body ratio than expected, potentially indicating higher cognitive capabilities in these herbivorous dinosaurs. Some researchers have identified structures they interpret as cortical tissues arranged in patterns similar to those seen in modern birds, which could suggest neural organization more advanced than previously attributed to dinosaurs. Additionally, the apparent blood vessel arrangements might provide insights into dinosaur metabolism and thermoregulation. These potential revelations explain why paleontologists remain so invested in resolving the debate—the specimen could fundamentally alter our understanding of dinosaur intelligence and physiology if the brain interpretation proves correct.

Testing Methodologies and Reproducibility

A cornerstone of scientific credibility is the ability to reproduce results, yet the unique nature of the Sussex specimen presents significant challenges in this regard. The research team has employed multiple analytical techniques—including scanning electron microscopy, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy, and computed tomography—to build their case for preserved brain tissue. However, destructive testing that might provide more definitive evidence remains controversial, as it would damage this potentially invaluable specimen. Some scientists have called for additional non-destructive tests, such as synchrotron radiation analysis, which could provide higher-resolution chemical mapping without damaging the fossil. Others suggest that experimental approaches, such as attempting to replicate the proposed preservation conditions with modern animal brain tissue, might help resolve the debate. The lack of consensus on appropriate testing methodologies continues to hamper definitive resolution of the controversy.

Future Research Directions

As technology advances, new approaches may help resolve the debate surrounding the Sussex specimen. Emerging techniques in molecular paleontology could potentially detect specific proteins or other biomolecules that would be uniquely associated with brain tissue as opposed to bacterial biofilms or other explanations. Advanced imaging technologies continue to improve, potentially offering non-destructive ways to examine the internal structure of the specimen at increasingly fine resolutions. Some researchers suggest that machine learning algorithms could be trained on known brain tissues and biofilms to help distinguish between these possibilities in the fossil. Additionally, taphonomic experiments that attempt to recreate the proposed preservation conditions using modern analogues could test whether brain tissue preservation is theoretically possible under the conditions proposed. As these research directions develop, scientists hope that the true nature of this enigmatic fossil will eventually be resolved with greater confidence.

The Broader Impact on Paleontology

Regardless of its final interpretation, the Sussex specimen has already made a significant impact on paleontology. The debate has stimulated important discussions about the limits of preservation and the standards of evidence required for extraordinary claims in paleontology. It has spurred methodological innovations as researchers develop new techniques to analyze potential soft tissue preservation. The controversy has also highlighted the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration, bringing together experts in paleontology, chemistry, microbiology, and taphonomy to address complex questions about ancient life. Perhaps most importantly, it has captured public imagination and interest in paleontology, demonstrating that fundamental questions about prehistoric life remain unanswered even after centuries of fossil hunting. The story of the potential dinosaur brain serves as a powerful reminder that paleontology remains a dynamic field where significant discoveries and scientific debates continue to unfold.

Conclusion

The debate over the Sussex specimen exemplifies science at its most fascinating—where extraordinary claims meet rigorous skepticism, and where definitive answers remain elusive despite advanced technology. Whether this brownish fossil truly represents the preserved brain of a dinosaur that lived over 130 million years ago, or something else entirely, the investigation continues to push the boundaries of paleontological science. As researchers develop new techniques and gather additional evidence, the true nature of this remarkable specimen may eventually be determined. Until then, the potential dinosaur brain remains one of paleontology’s most intriguing mysteries—a testament to the endless wonders still waiting to be uncovered in Earth’s fossil record.