In the world of paleontology, few stories capture the intersection of science, ethics, and international law quite like the saga of Tarbosaurus bataar, sometimes called “the Mongolian T. rex.” This remarkable fossil, extracted from the Gobi Desert, became the center of a high-stakes international controversy that would ultimately redefine how the scientific community and legal systems approach the protection of prehistoric treasures. The case highlighted the growing black market for fossils and forced museums, collectors, and governments to reconsider their policies on acquisition and ownership of paleontological specimens. What follows is the extraordinary journey of a 70-million-year-old dinosaur that traveled from ancient Mongolia to the modern auction block, before finally returning home after a landmark legal battle.

The Gobi Desert’s Paleontological Treasures

The Gobi Desert spans across southern Mongolia and northern China, representing one of the world’s richest dinosaur fossil beds. Since the 1920s, when Roy Chapman Andrews led expeditions into this remote region, the Gobi has yielded countless remarkable specimens that have revolutionized our understanding of dinosaur evolution. The Nemegt Formation, dating to the Late Cretaceous period approximately 70 million years ago, has been particularly fertile ground for paleontologists. This geological layer has produced numerous specimens of Tarbosaurus bataar, a close relative of North America’s Tyrannosaurus rex. The preservation quality in the Gobi is often exceptional due to the arid conditions and rapid burial of specimens, resulting in articulated skeletons rather than scattered fragments. Mongolia has strict laws forbidding the export of fossils found within its borders, considering them national treasures integral to the country’s natural heritage.

The Theft: Smuggling a Dinosaur

Sometime in the late 2000s, commercial fossil hunters illegally excavated an exceptionally complete Tarbosaurus bataar skeleton from the Gobi Desert. Rather than being carefully documented and extracted by trained paleontologists, this specimen was hastily removed, likely causing damage to both the fossil and its surrounding geological context that could have provided valuable scientific information. The 8-foot-tall, 24-foot-long skeleton was disassembled and smuggled out of Mongolia through a complex network of international borders and black market dealers. The fossil traffickers falsified documents to disguise the specimen’s Mongolian origin, claiming it came from Great Britain, where no such dinosaurs ever lived. This elaborate smuggling operation highlights the sophisticated nature of the illegal fossil trade, which some experts estimate to be worth tens of millions of dollars annually. The removal of this specimen was not only scientifically damaging but also represented a significant cultural theft from the Mongolian people.

The Commercial Fossil Market

The illegal extraction of the Tarbosaurus skeleton reflects the troubling growth of commercial fossil hunting and trading that gained momentum in the 1990s. Following the 1997 auction of “Sue,” a Tyrannosaurus rex skeleton that sold for $8.36 million to Chicago’s Field Museum, fossils increasingly became viewed as luxury items and investment opportunities rather than scientific specimens. This commercialization created a problematic incentive structure where rare fossils could command prices in the millions, encouraging black market activity and illegal excavations worldwide. Legitimate auction houses and fossil dealers often find themselves in an ethical gray area, where documentation of a specimen’s origins may be insufficient or deliberately obscured. Commercial fossil hunting differs dramatically from scientific paleontology in its methods and goals – while scientists meticulously document the position and context of each bone, commercial hunters often focus solely on extracting marketable specimens as quickly as possible. The tension between scientific access and private ownership of significant fossils continues to challenge the paleontological community.

The Auction That Raised Red Flags

In May 2012, the stolen Tarbosaurus bataar skeleton appeared in a glossy Heritage Auctions catalog, advertised as the centerpiece of a natural history auction in New York City. The specimen was described as “a superb Tyrannosaurid, which measures 24 feet in length, stands 8 feet high, and is 75% complete.” With a presale estimate of $950,000 to $1.5 million, the skeleton immediately caught the attention of paleontologists who recognized it as almost certainly originating from Mongolia. Mongolian paleontologist Bolortsetseg Minjin was among the first to raise concerns, alerting Mongolian officials and American paleontologists about the suspicious auction lot. A team of experts, including fossil vertebrate specialist Mark Norell from the American Museum of Natural History, quickly published an open letter noting that “there is no legal mechanism (nor has there been for over 50 years) to remove vertebrate fossil material from Mongolia.” Despite these objections and a temporary restraining order requested by the Mongolian government, Heritage Auctions proceeded with the sale, with the skeleton fetching $1.05 million from an anonymous buyer.

Mongolia’s Legal Challenge

The Mongolian government, upon learning of the planned auction, launched an unprecedented legal challenge to recover what it considered stolen national property. President Tsakhiagiin Elbegdorj personally directed his government to take all necessary measures to repatriate the dinosaur skeleton. Mongolia retained experienced attorney Robert Painter, who dramatically appeared at the auction with a temporary restraining order signed by a Texas judge, though the auction house proceeded with the sale nonetheless. This bold move marked the beginning of Mongolia’s determined effort to reclaim its paleontological heritage. The Mongolian government argued that since 1924, all fossils discovered within Mongolia’s borders have been protected as national property, making the export of the Tarbosaurus skeleton unquestionably illegal regardless of how it left the country. This case represented the first time a source country had so aggressively pursued the return of illegally exported fossils through the American legal system. Mongolia’s action set an important precedent for other nations with rich paleontological resources but limited means to protect them from international traffickers.

The Federal Investigation

Following the controversial auction, the United States government launched a formal investigation into the provenance of the Tarbosaurus skeleton. The case was assigned to the Homeland Security Investigations division and the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York, which specializes in handling cultural property crimes. Federal agents traced the fossil’s journey through multiple countries and false documentation, gradually building a case that would demonstrate the illegal nature of the specimen’s importation into the United States. The investigation revealed that import documents falsely claimed the skeleton originated in Great Britain, when scientific evidence conclusively demonstrated it came from the Nemegt Formation in Mongolia. Investigators discovered the fossil had entered the United States in multiple shipments labeled as “reptile fossil pieces,” dramatically undervaluing the contents at just a few thousand dollars to avoid scrutiny. This federal investigation represented one of the most significant applications of cultural property laws to paleontological specimens, establishing that dinosaur fossils could be considered cultural patrimony in the same legal category as archaeological artifacts.

The Florida Fossil Dealer

The federal investigation eventually identified Eric Prokopi, a commercial fossil dealer from Gainesville, Florida, as the central figure in the importation and attempted sale of the Tarbosaurus skeleton. Prokopi, who called himself a “commercial paleontologist,” had established a reputation for preparing and mounting dinosaur skeletons for private collectors and commercial sale. Federal prosecutors charged Prokopi with multiple crimes, including conspiracy to smuggle illegal goods, entry of goods using false statements, and interstate transportation of stolen property. Facing substantial prison time, Prokopi eventually pleaded guilty in December 2012 and agreed to forfeit not only the Tarbosaurus bataar skeleton but also several other dinosaur specimens he had imported from Mongolia and China. As part of his cooperation with authorities, Prokopi provided valuable information about the broader fossil smuggling network, which helped investigators identify additional illegally exported specimens. His case illustrated the previously blurry line between legitimate commercial fossil dealing and illegal trafficking, bringing new scrutiny to the entire industry of private fossil sales.

The Scientific Evidence

Central to the legal case was the scientific evidence establishing the Mongolian origin of the Tarbosaurus skeleton. Paleontologists provided expert testimony that the specimen could only have come from the Nemegt Formation in Mongolia, based on several converging lines of evidence. The fossil’s distinctive reddish-brown coloration matched the iron-rich sandstone of the Nemegt Formation, and the preservation style, with specific types of mineralization, was consistent with other specimens known from that geological context. Most conclusively, Tarbosaurus bataar fossils have only ever been found in Mongolia and adjacent parts of China, making any claim about alternative origins scientifically impossible. The matrix (surrounding rock material) still attached to portions of the skeleton provided geochemical signatures that could be matched specifically to the Gobi Desert formations. This scientific certainty about the specimen’s origin played a crucial role in the legal proceedings, demonstrating that paleontological expertise could provide forensic evidence strong enough to support criminal charges. The case highlighted the value of scientific knowledge in combating the illegal fossil trade.

The Legal Precedent

The Tarbosaurus bataar case established a groundbreaking legal precedent for the protection and repatriation of paleontological specimens. On February 13, 2013, a U.S. District Court judge signed a forfeiture order declaring that the United States would return the skeleton to Mongolia, marking the first time U.S. courts had ordered the return of a dinosaur fossil to its country of origin. This ruling effectively recognized that paleontological specimens could be protected under the same legal frameworks as archaeological artifacts and other cultural property. The case relied on the application of the National Stolen Property Act, demonstrating that even if the fossil had been taken from Mongolia decades earlier, it remained stolen property under U.S. law because it had been exported in violation of clear Mongolian patrimony laws. This interpretation strengthened the legal position of countries with rich fossil resources but limited means to police their extraction. The successful prosecution sent a powerful message to fossil dealers and collectors worldwide that the legal risks of trafficking in illegally obtained specimens had increased substantially.

The Repatriation Ceremony

On May 6, 2013, less than a year after the controversial auction, the United States officially returned the Tarbosaurus bataar skeleton to Mongolia in a formal ceremony held in New York. Mongolian President Tsakhiagiin Elbegdorj personally attended the handover, underscoring the national significance of the repatriation. The ceremony represented not just the return of a single specimen but a symbolic victory for countries fighting to protect their paleontological heritage from international trafficking. In his remarks, President Elbegdorj emphasized that the dinosaur represented an important part of Mongolia’s natural history and cultural identity that belonged in its homeland, where Mongolian scientists and citizens could study and appreciate it. U.S. officials used the occasion to reaffirm their commitment to combating the illegal trade in cultural property, including fossils. The carefully crafted skeleton began its journey home to Mongolia, where plans were already underway for its permanent installation in a new museum. The repatriation marked the beginning of a new chapter in international cooperation to protect fossil resources.

The Central Mongolian Dinosaur Museum

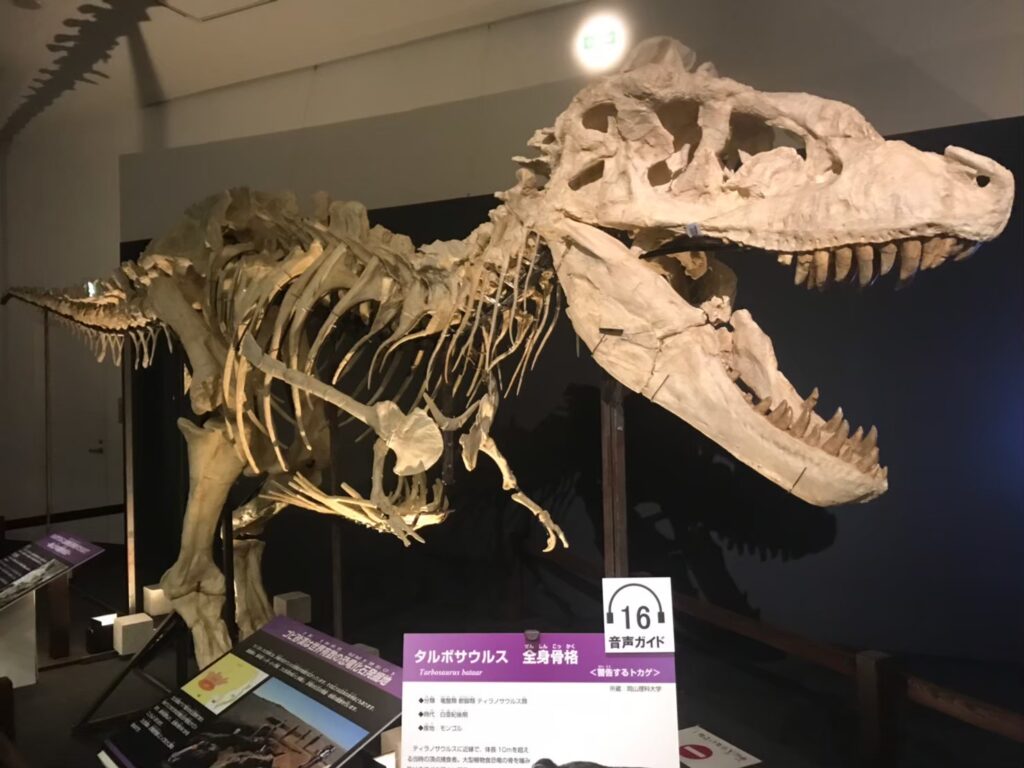

Following its return to Mongolia, the Tarbosaurus bataar skeleton became the centerpiece of the new Central Museum of Mongolian Dinosaurs in Ulaanbaatar, a facility specifically created to house this and other repatriated specimens. The museum opened its doors in 2013, transforming what had been the Lenin Museum during the Soviet era into a showcase for Mongolia’s prehistoric natural heritage. The restored and properly mounted Tarbosaurus now serves as both a scientific specimen and a powerful symbol of national heritage reclaimed. The museum has become an important educational resource for Mongolian citizens, particularly schoolchildren who can now see their country’s paleontological treasures without traveling abroad. Beyond housing the repatriated specimens, the museum has catalyzed the development of paleontology within Mongolia, providing opportunities for Mongolian scientists to study these fossils in their home country rather than having to visit foreign institutions. The establishment of this museum represents a significant step in Mongolia’s efforts to take greater control over the study and preservation of its fossil resources, building scientific capacity within the country.

The Continuing Recovery Efforts

The successful repatriation of the Tarbosaurus bataar skeleton catalyzed ongoing efforts to recover other Mongolian fossils that had been illegally exported over the decades. Following the precedent established by this case, the Mongolian government, working with international partners, has identified and secured the return of numerous additional specimens from private collections, auction houses, and even museums worldwide. By 2016, more than 30 dinosaur specimens had been returned to Mongolia as a direct result of the increased awareness and legal precedent established by the Tarbosaurus case. The United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency created a dedicated initiative to identify potentially stolen fossils in American collections, leading to multiple additional seizures and voluntary returns. Mongolia established more formal procedures for legitimate scientific expeditions to study fossils within its borders, balancing the protection of its resources with the advancement of paleontological knowledge. The ripple effects of the case extended to other fossil-rich countries like China, Argentina, and Brazil, which have strengthened their patrimony laws and enforcement efforts against fossil trafficking.

The Impact on Museums and Private Collectors

The Tarbosaurus bataar case profoundly altered practices within museums, auction houses, and among private collectors regarding the acquisition of significant fossils. Major museums worldwide implemented more stringent provenance requirements for new acquisitions, often requiring documented evidence of legal export from the country of origin before considering purchases or donations. Auction houses instituted enhanced due diligence procedures for fossil consignments, requiring sellers to provide more comprehensive documentation about a specimen’s history. Private collectors became increasingly cautious about purchasing specimens without clear provenance, as the case demonstrated that even fossils acquired years earlier could potentially be subject to seizure and repatriation. The value of fossils with questionable provenance declined significantly in the legitimate market, though unfortunately, this may have driven some transactions further underground. Many institutions began reviewing their existing collections for potentially problematic specimens that might have been acquired before stronger ethical standards were established. These changes collectively represent a significant shift toward greater ethical responsibility in paleontological collecting and curation.

The Ethical Debate in Paleontology

The controversy surrounding the Tarbosaurus bataar intensified an already brewing ethical debate within the paleontological community about the relationship between commercial fossil dealers, private collectors, and academic science. Some paleontologists argue that private collecting inevitably leads to the loss of scientific information and damages the integrity of the fossil record, advocating for all scientifically significant specimens to remain in public institutions. Others contend that responsible private collectors and ethical commercial dealers play an important role in discovering and preserving fossils that might otherwise erode unnoticed, pointing to numerous cases where important scientific specimens were initially found by commercial collectors. The case highlighted the tension between national ownership laws and the international nature of paleontological research, raising questions about how to balance a country’s sovereignty over its fossil resources with the advancement of scientific knowledge as a global endeavor. Many in the field now advocate for collaborative models where commercial collectors, private enthusiasts, and professional scientists can work together within legal frameworks that protect both scientific information and national patrimony rights. The ongoing conversation has led to more nuanced ethical guidelines from professional societies and greater awareness of these issues among all stakeholders.

The Legacy of the Tarbosaurus Case

More than a decade after the dramatic auction that brought international attention to fossil trafficking, the legacy of the Tarbosaurus bataar case continues to shape paleontology, law enforcement, and museum practices worldwide. The successful prosecution and repatriation demonstrated that countries of origin could effectively reclaim illegally exported fossils through international legal cooperation, establishing a model that has since been followed in numerous other cases. The enhanced scrutiny of fossil provenance has generally improved scientific documentation, as collectors and institutions now recognize the importance of maintaining detailed records about a specimen’s discovery and subsequent history. Mongolia has developed greater capacity for managing its paleontological resources, including training more native Mongolian paleontologists and establishing improved facilities for fossil storage and research. The case has become required reading in museum studies programs and paleontological ethics courses, educating the next generation of professionals about these complex issues. Perhaps most importantly, the Tarbosaurus bataar skeleton, once destined for a private collection where few would see it, now stands as a public treasure in its homeland, accessible to the very people whose natural heritage it represents.