The oceans of our planet have witnessed numerous dominant species throughout Earth’s lengthy history. From ancient arthropods to modern marine mammals, various groups have risen to ecological prominence in aquatic environments. However, one fascinating counterfactual scenario rarely explored is what might have happened if dinosaurs, rather than remaining predominantly terrestrial creatures, had evolved to dominate ocean ecosystems instead. While some marine reptiles like plesiosaurs and ichthyosaurs did flourish in prehistoric seas, they weren’t true dinosaurs. This article explores the fascinating hypothetical scenario where dinosaurs themselves became the primary oceanic predators and ecosystem engineers, fundamentally reshaping marine evolution and perhaps even altering the course of life on Earth.

The Evolutionary Pathway to Marine Dominance

For dinosaurs to become marine dominants, they would have needed specific evolutionary adaptations pushing them toward aquatic lifestyles. This hypothetical transition might have begun with coastal dinosaur species gradually spending more time in shallow waters, perhaps hunting fish or escaping terrestrial predators. Over millions of years, natural selection would favor individuals with more streamlined bodies, paddle-like limbs, and respiratory systems adapted for extended underwater periods. The transition would mirror evolutionary pathways we’ve observed in other terrestrial-to-marine transitions, such as those seen in the ancestors of whales, seals, and sea turtles. Certain dinosaur groups like the theropods (which included species like Velociraptor and T. rex) might have been particularly well-positioned for such adaptations due to their already efficient body plans and metabolic systems.

Anatomical Transformations

The physical transformation of dinosaurs adapting to marine environments would have been dramatic and comprehensive. Limbs would evolve from walking appendages to powerful flippers or paddle-like structures optimized for propulsion through water. Their bodies would become more hydrodynamic, with smoother contours and possibly dorsal fins for stability. Respiratory systems would need significant modification, potentially developing larger lung capacities or even specialized breathing mechanisms similar to those seen in modern diving birds. Their skeletal structure would likely change dramatically too, with modifications to bone density to manage buoyancy at different depths. Sensory systems would adapt as well, with enhanced vision for underwater hunting and possibly the development of pressure-sensitive organs similar to the lateral line system found in fish.

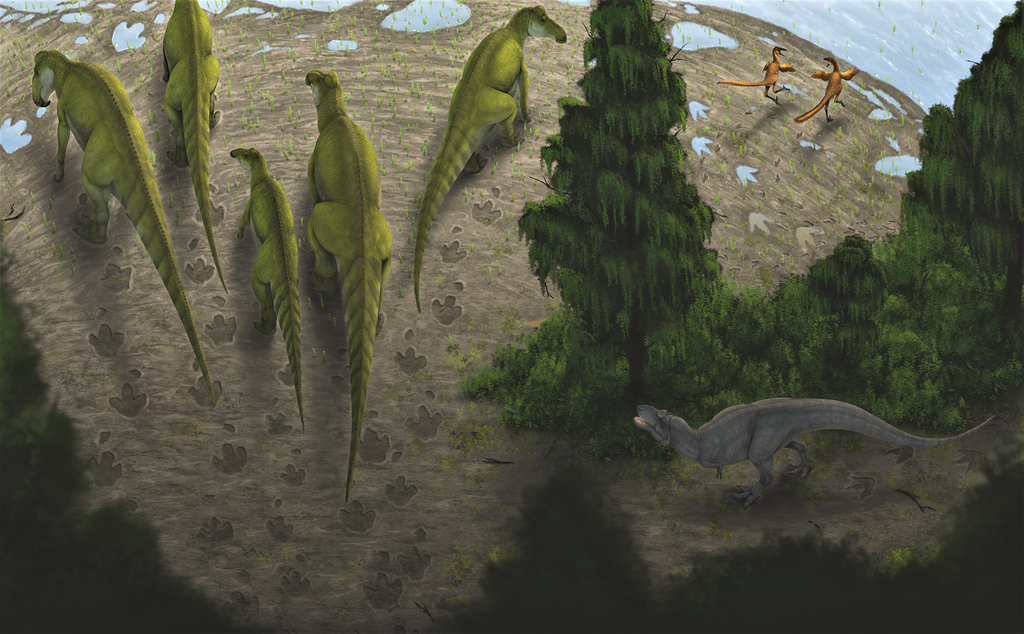

Marine Dinosaur Diversity

In this alternate evolutionary timeline, the ocean would likely feature a stunning diversity of specialized dinosaur species. Massive predatory marine theropods might evolve to fill niches similar to modern orcas or ancient mosasaurs, becoming apex predators that hunted large prey. Smaller, agile dinosaur species could specialize in hunting schools of fish or squid-like creatures. Some might evolve filter-feeding adaptations similar to modern baleen whales, straining tiny organisms from the water with specialized mouth structures. Deep-diving specialists would develop pressure-resistant anatomies for hunting in the ocean’s twilight zones. We might even see herbivorous marine dinosaurs grazing on coastal seaweed beds or specialized algae, creating entirely novel ecological niches that don’t exist in our timeline.

The Fate of Existing Marine Reptiles

Had dinosaurs ventured successfully into the oceans, they would have encountered established marine reptile groups like plesiosaurs, ichthyosaurs, and mosasaurs that were already well-adapted to aquatic life. This encounter would likely trigger intense evolutionary competition for resources and hunting territories. The outcome of this competition would depend largely on the specific adaptations dinosaurs brought to marine environments. If dinosaur-derived marine species possessed advantages like superior intelligence, more efficient metabolisms, or better hunting strategies, they might gradually outcompete these other marine reptiles. Alternatively, the different groups might specialize in distinct ecological niches, coexisting through evolutionary differentiation and resource partitioning, much as different marine mammal groups do today.

Impact on Marine Ecosystem Structure

The dominance of dinosaurs in ocean ecosystems would dramatically reshape marine food webs and ecological relationships. As both top predators and potentially abundant middle-trophic level consumers, marine dinosaurs would exert powerful top-down control on prey populations. Their hunting behaviors and feeding patterns would select for different defensive adaptations in prey species compared to our timeline. The sheer biomass of large marine dinosaurs would also affect nutrient cycling in the oceans, potentially creating different patterns of primary productivity. Large, migratory marine dinosaur species might transport nutrients between different ocean regions, similar to the “whale pump” effect observed with modern cetaceans, where deep-feeding whales bring nutrients to surface waters through their excrement.

Surviving the K-Pg Extinction Event

One of the most intriguing aspects of this alternate history involves the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) extinction event approximately 66 million years ago. In our timeline, this catastrophic asteroid impact and its aftermath wiped out all non-avian dinosaurs but spared some marine species. Marine dinosaurs might have had better survival odds during this cataclysm than their terrestrial counterparts. Ocean environments provide some buffering against temperature extremes, and marine food webs can be more resilient to certain types of disruption. Deep-diving marine dinosaur species might have accessed food sources less affected by the initial catastrophe. If some marine dinosaur lineages survived this extinction filter, they could have experienced an evolutionary radiation in the aftermath, potentially preventing mammals from dominating the marine realm as they eventually did in our timeline.

Competition with Marine Mammals

Had marine dinosaurs survived into the Cenozoic Era, they would have eventually faced competition from the emerging marine mammals. In our actual evolutionary history, groups like whales, dolphins, seals, and sea lions evolved from terrestrial mammal ancestors beginning around 50 million years ago. In this alternate timeline, these mammals would encounter oceans already dominated by well-established marine dinosaur lineages with tens of millions of years of aquatic adaptation. This competitive scenario might have limited marine mammal diversification or pushed mammals toward more specialized niches that dinosaurs hadn’t fully exploited. Alternatively, if mammals possessed significant advantages—perhaps related to intelligence, social behavior, or reproductive strategies—they might still have displaced dinosaurs from certain ecological roles despite the dinosaurs’ head start.

Potential Intelligence and Social Structures

An especially fascinating aspect of marine dinosaur evolution would be the potential development of advanced intelligence and complex social behaviors. Many modern marine predators, particularly cetaceans, have evolved remarkable cognitive abilities and sophisticated social structures. These adaptations seem to be responses to the challenges and opportunities of marine environments, where coordinated hunting, long-distance communication, and information sharing provide significant advantages. If dinosaurs followed similar selective pressures, we might see the evolution of highly intelligent marine dinosaur species with brain-to-body ratios approaching those of dolphins or orcas. These species might develop pod structures, hunting cooperatively and possibly even developing distinctive cultural traditions passed down through generations.

Reproductive Adaptations for Marine Life

Reproduction would represent a critical evolutionary challenge for marine dinosaurs. As reptiles, dinosaurs would likely retain egg-laying reproduction rather than evolving live birth as mammals did. This would necessitate returning to land for nesting, creating vulnerable periods in their life cycle similar to modern sea turtles. Over time, we might see the evolution of specialized breeding behaviors, with dinosaurs returning to specific beaches to lay eggs, potentially in massive synchronized nesting events to overwhelm predators. Alternatively, some lineages might evolve ovoviviparity (where eggs develop inside the mother and hatch just before or after birth) or even true viviparity (live birth) as seen in some modern reptiles like certain skinks and sea snakes, allowing them to remain fully marine throughout their life cycle.

Migratory Patterns and Global Distribution

Marine dinosaurs would likely develop extensive migratory patterns across the world’s oceans, responding to seasonal changes in food availability, breeding requirements, and temperature fluctuations. Large filter-feeding species might undertake journeys similar to modern humpback whales, traveling between productive feeding grounds in cooler waters and warmer breeding areas. Predatory species could follow migrations of prey species or move between different hunting territories seasonally. These migratory patterns would influence global ocean ecology, creating pulses of predation pressure in different regions at different times. The geographic distribution of marine dinosaur species would be shaped by ocean currents, temperature tolerances, and continental arrangements, potentially creating distinct provincial faunas in different ocean basins.

Human Interaction with Marine Dinosaurs

If marine dinosaurs had survived to the present day, human civilization would have developed alongside these impressive ocean dwellers, creating a dramatically different relationship with the sea. Early human maritime cultures would have contended with predatory marine dinosaurs as a significant hazard to fishing and sea travel. Mythology and cultural practices would incorporate these creatures, perhaps as fearsome sea monsters or revered ocean deities. In the modern era, some species might face exploitation and hunting pressures similar to what whales experienced, while others might become protected through conservation efforts. Marine dinosaur watching could become a major ecotourism industry, while naval and shipping operations would need to account for the presence of these large marine animals. The ethical questions surrounding the captivity of intelligent marine species would extend beyond dolphins and orcas to potentially self-aware dinosaur species.

Implications for Modern Marine Conservation

A world with dominant marine dinosaurs would present significantly different conservation challenges than our current reality. Modern marine ecosystems are largely shaped by human activities like overfishing, pollution, and climate change. Marine dinosaurs, especially large predatory species, would be particularly vulnerable to these pressures due to their likely K-selected life histories (long-lived, slow to reproduce). Their existence might have spurred earlier conservation movements as their decline would be more immediately noticeable than the gradual depletion of fish stocks. Alternatively, if marine dinosaurs had evolved to be particularly dangerous to humans, their conservation might be more controversial, with some groups advocating for culling programs to protect maritime activities. Marine protected areas would need to account for the extensive migratory ranges of these animals, potentially driving larger international conservation agreements.

A Different View of Evolutionary History

This counterfactual scenario offers valuable insights into evolutionary contingency—how history might have unfolded differently with slight changes to initial conditions. In our actual timeline, dinosaurs remained predominantly terrestrial, with birds as their only surviving descendants. Marine niches were filled by other reptile groups and later by mammals. This hypothetical marine dinosaur dominance reminds us that evolution doesn’t follow predetermined paths toward inevitable outcomes. Different groups can evolve similar adaptations to similar environments—a process called convergent evolution—but which groups occupy which niches often depends on historical accident and opportunity. Understanding these contingencies helps us appreciate that the current arrangement of life on Earth represents just one of countless possible evolutionary outcomes, making our actual biodiversity all the more precious and worthy of protection.

Conclusion

The scenario of dinosaurs becoming the dominant ocean species presents a fascinating alternate evolutionary history that illuminates many aspects of actual biological processes. While this hypothetical marine dinosaur dominance never materialized, exploring such counterfactuals helps us understand the forces that shape evolution and biodiversity. It highlights the importance of opportunity, adaptation, and historical contingency in determining which groups succeed in which environments. The real marine reptiles that did evolve—the ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs, and mosasaurs—provide glimpses of what might have been had true dinosaurs made the transition to marine life. This thought experiment also gives us greater appreciation for the remarkable adaptations of the marine mammals that actually did evolve to dominate our oceans, from the enormous blue whale to the intelligent dolphin, reminding us that the natural world as we know it represents just one branch of a vast tree of evolutionary possibilities.