The question of where dinosaurs rested their massive bodies after a day of hunting or grazing remains one of paleontology’s most fascinating mysteries. These magnificent creatures dominated Earth for over 165 million years, yet the intimate details of their sleeping habits have largely been left to scientific inference and careful examination of fossil evidence. Unlike behavior that might leave obvious traces in the fossil record, such as feeding or migration, sleeping is a relatively passive activity that leaves few direct clues. Nevertheless, by examining modern animal behavior, fossil evidence, and paleoenvironmental data, scientists have developed compelling theories about dinosaur sleeping habits, from the wide-open grasslands to the protective canopies of prehistoric forests.

The Challenge of Studying Prehistoric Sleep

Studying dinosaur sleeping habits presents unique challenges for paleontologists who must work with incomplete evidence. Unlike behavioral patterns that might leave clear traces in the fossil record, such as feeding marks on bones or trackways showing movement, sleep rarely leaves direct evidence. Scientists must therefore rely on a combination of rare fossil finds, comparisons with modern animals, and understanding of the prehistoric environments in which dinosaurs lived. Occasionally, fossils are discovered that appear to show dinosaurs in resting positions, providing valuable glimpses into this aspect of their daily lives. These exceptional discoveries, combined with knowledge of dinosaur anatomy and physiology, allow researchers to make educated inferences about where and how different dinosaur species might have slept. The absence of direct observation means that many theories remain speculative, though grounded in scientific reasoning.

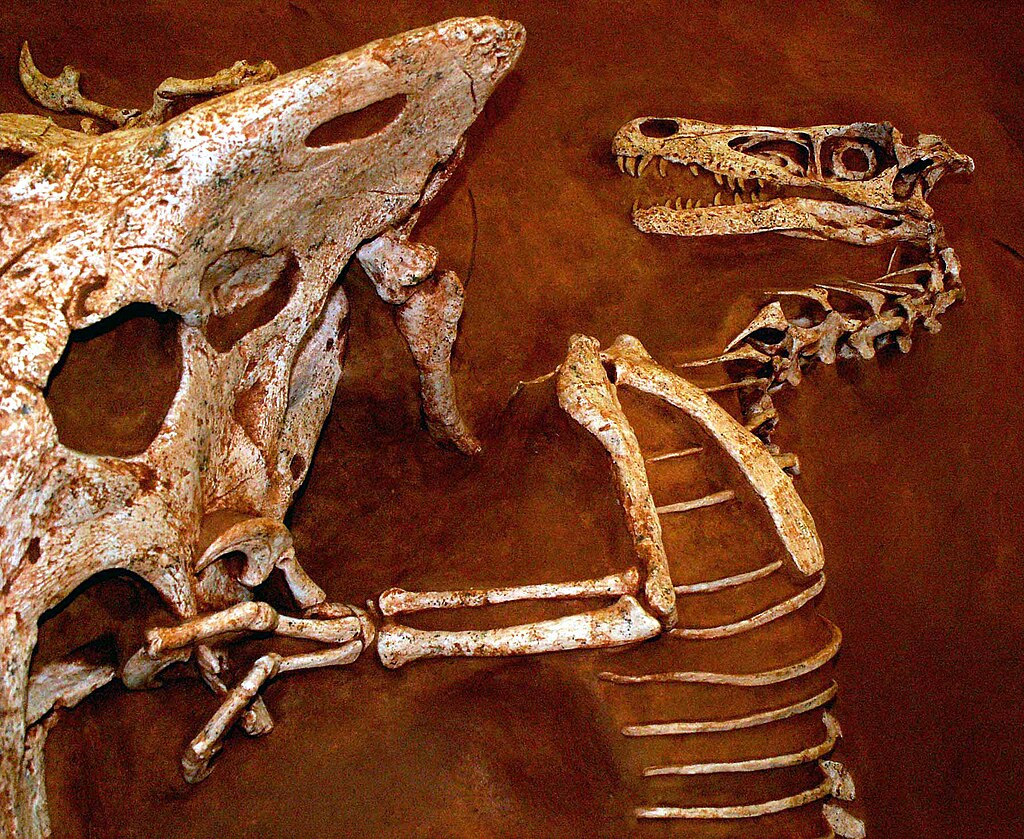

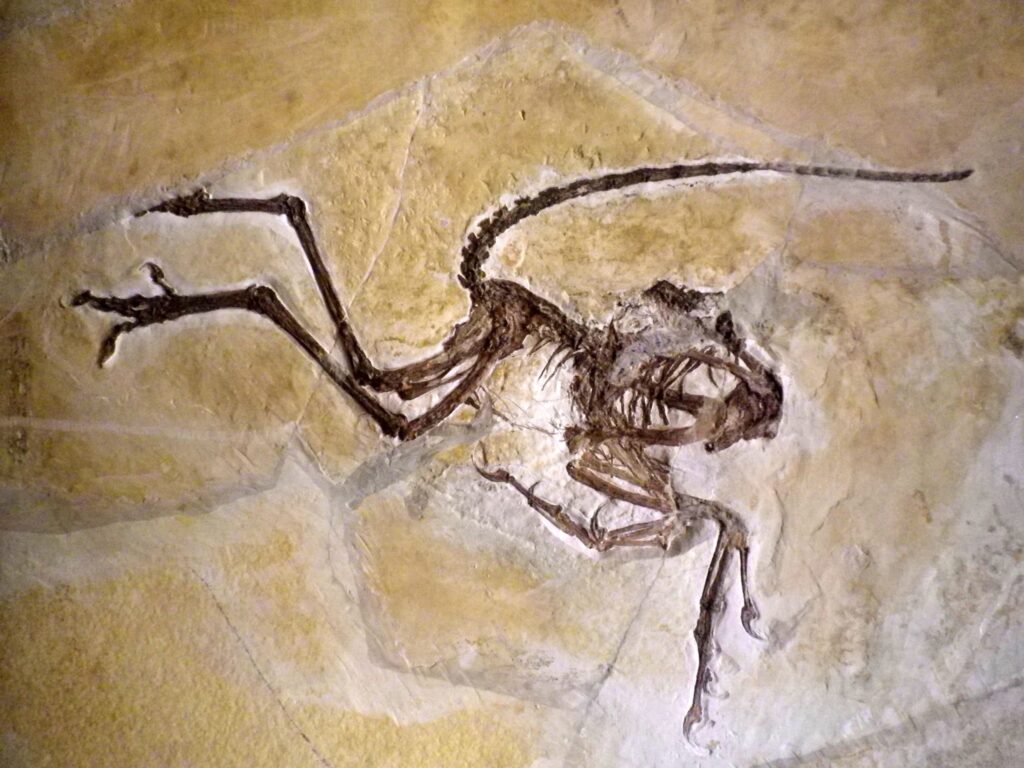

Fossil Evidence of Sleeping Dinosaurs

Several remarkable fossil discoveries have provided direct evidence of dinosaur resting positions, offering crucial insights into their sleeping habits. Perhaps the most famous is the “fighting dinosaurs” fossil from Mongolia, which shows a Velociraptor and Protoceratops locked in combat, suggesting the predator may have disturbed its prey during rest. Another significant find is the “sleeping dragon” fossil (Mei long) discovered in China, preserved in a bird-like sleeping posture with its head tucked under its arm, indicating a sleep position remarkably similar to modern birds. The dinosaur Sinornithoides was also found in a similar sleeping position, reinforcing the bird-like sleeping behavior of certain theropod dinosaurs. These fossils are exceptionally rare because they require rapid burial during or shortly after death to preserve such delicate positioning. When such fossils are discovered, they provide valuable windows into dinosaur behavior that would otherwise remain hidden from scientific understanding.

Open Plains: Advantages for Large Herbivores

For massive herbivorous dinosaurs like the long-necked sauropods and certain large ornithischians, open plains may have offered practical sleeping arrangements that accommodated their enormous size. These environments would have allowed herds to rest together, providing safety in numbers against predators that might target individuals during vulnerable sleeping hours. The open visibility would have been advantageous, allowing at least some members of the herd to spot approaching dangers from a distance, similar to how modern elephants and other large herbivores operate. Additionally, large dinosaurs may have struggled to navigate dense forests, making open plains more accessible for leaping. The thermal properties of open areas could also have been beneficial, allowing these massive animals to regulate their body temperature more effectively through the night, especially if they had complex thermoregulatory systems. Evidence from trackways and fossilized flora suggests many herbivorous dinosaurs indeed spent significant time in open plains environments.

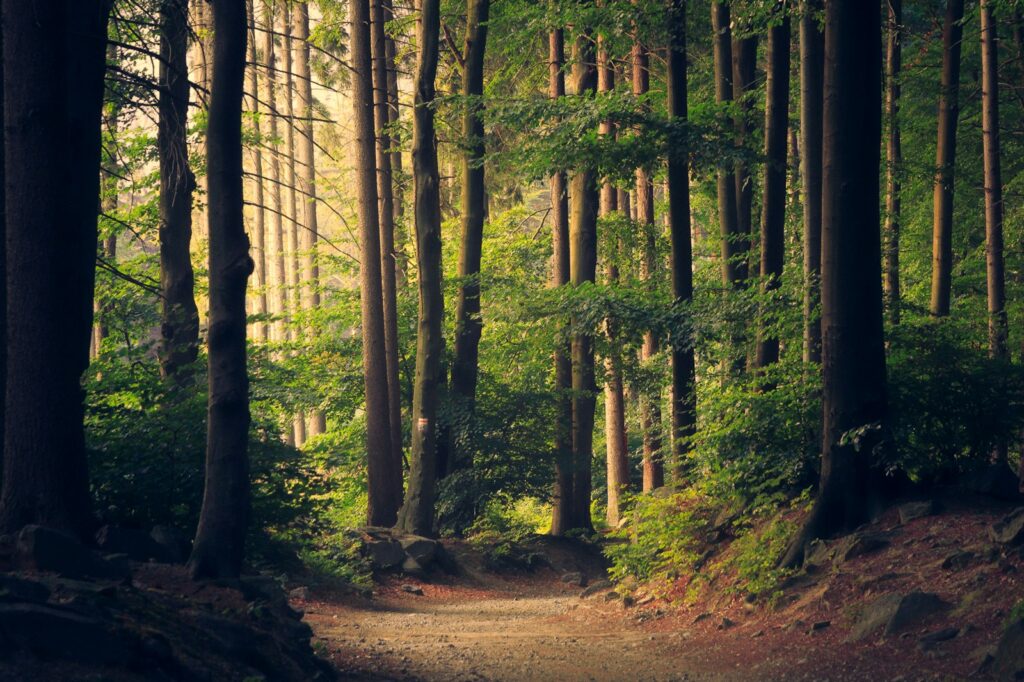

Forest Refuges: Protection for Smaller Species

Smaller dinosaur species likely favored the protective cover of forests and dense vegetation for their sleeping locations. These environments would have provided crucial concealment from predators, particularly for vulnerable juveniles and smaller species that couldn’t rely on sheer size for protection. Forests would have offered numerous hiding spots among fallen logs, dense underbrush, and tree canopies for arboreal species. The dense vegetation would have also created beneficial microhabitats with more stable temperatures and humidity levels, potentially helping smaller dinosaurs conserve energy during rest periods. Fossil evidence supports this theory, as many smaller dinosaur specimens have been discovered in what were once forested areas, preserved alongside fossilized plants that indicate dense vegetation. For nocturnal species, forests would have provided essential daytime hiding spots from larger predators that hunted primarily in open areas. This pattern mirrors the behavior of many modern smaller animals that seek shelter in complex habitats.

Arboreal Roosting: Did Some Dinosaurs Sleep in Trees?

Evidence strongly suggests that certain dinosaur species, particularly small feathered theropods and primitive birds, likely slept in trees much like their modern avian descendants. The discovery of dinosaurs like Microraptor and Archaeopteryx, with features adapted for some degree of tree-dwelling, supports this theory. These adaptations include long forelimbs, curved claws that would have been excellent for gripping branches, and in some cases, feathers that would have aided in balance and insulation during arboreal rest periods. Sleeping in trees would have provided significant protection from ground-dwelling predators, making it an excellent survival strategy for smaller species. The fossil record includes specimens of small dinosaurs with wrist adaptations that would have allowed them to fold their limbs against their bodies while perching, similar to modern birds. Paleoenvironmental reconstructions confirm that many dinosaur habitats contained tall trees and varied canopy structures that would have offered ample roosting opportunities for these more agile species.

Nesting Behavior vs. Regular Sleep Patterns

Dinosaur sleeping habits likely differed significantly from their nesting behaviors, though the two activities would have been connected through the need for safety. While nesting involved specific locations chosen for egg-laying and protection of young, with many species creating carefully constructed nests, everyday sleep probably involved less elaborate arrangements dictated by immediate needs and environments. Fossil evidence reveals that many dinosaur species nested in colonies, with nests arranged in patterns that suggest social organization, yet their daily sleep might have involved more flexible arrangements based on feeding locations and predator pressures. Some species may have returned to familiar sleeping grounds regularly, creating worn paths or subtle alterations to the landscape that, unfortunately, are rarely preserved in the fossil record. For species that guarded their nests, sleeping and nesting locations would have overlapped during breeding seasons, with adults possibly taking turns keeping watch while others rested. The distinction between these behaviors helps paleontologists better understand the complex social and survival strategies employed by different dinosaur groups.

Sleeping Postures of Different Dinosaur Groups

Different dinosaur groups likely adopted distinct sleeping postures based on their anatomy and physiology. Theropods, including the ancestors of modern birds, appear to have often slept in a bird-like position with limbs folded and heads tucked, as evidenced by fossils like Mei long. Large sauropods, with their massive bodies, almost certainly slept standing or lying on their sides, as their sheer weight would have made it difficult to rise quickly from more complicated positions. Many ornithischians, particularly the quadrupedal varieties like Triceratops, may have slept in positions similar to modern rhinoceroses or elephants, either standing during light sleep or lying down for deeper rest. Fossil evidence of skin impressions suggests that some dinosaurs had calluses or specialized skin patches that would have protected high-pressure points during rest. The diversity of sleeping postures reflects the remarkable variety of body forms across Dinosauria, with each group evolving resting positions that balanced comfort, safety, and the ability to quickly respond to threats. For some species, changing sleeping positions throughout life might have been necessary as they grew from small juveniles to massive adults.

Sleep Cycles and Circadian Rhythms in Dinosaurs

Understanding dinosaur sleep cycles requires examining evidence from multiple sources, including brain anatomy, eye structure, and comparisons with living relatives. Studies of dinosaur endocasts (natural brain molds) suggest many species had well-developed optic lobes, indicating vision was an important sense that likely influenced their activity patterns. Some dinosaurs, particularly certain theropods, had large orbits that suggest adaptations for low-light conditions, potentially indicating nocturnal or crepuscular (dawn and dusk) activity patterns with daytime rest periods. Others, especially large herbivores, likely followed more diurnal patterns similar to modern large mammals, actively feeding during daylight hours and resting at night. The pineal gland, which regulates circadian rhythms in many vertebrates, appears to have been present in dinosaurs based on skull anatomy, suggesting they experienced regular sleep-wake cycles influenced by day-night patterns. Climate would have also played a role, with dinosaurs in extreme environments potentially altering their sleep patterns seasonally to avoid temperature extremes, similar to how modern desert animals may be nocturnal to avoid daytime heat.

Communal Sleeping: Safety in Numbers

Evidence strongly suggests that many dinosaur species engaged in communal sleeping behaviors, creating groups thaprotectedst predators during vulnerable resting hours. Multiple trackway sites have revealed patterns consistent with herding behavior in many dinosaur species, suggesting they likely maintained these social groupings during rest periods. Communal sleeping would have allowed for a vigilance system where some individuals could remain alert while others entered deeper sleep states, maximizing both rest and safety for the group. Juvenile dinosaurs would have particularly benefited from sleeping within adult groups, gaining protection during their most vulnerable life stage. For large herbivores, the combined mass of sleeping groups would have deterred all but the largest predators, while smaller theropods might have formed sleeping groups to better detect and collectively respond to threats. Fossilized nesting grounds showing multiple nests nearby provide indirect evidence for social behavior that likely extended to sleeping arrangements. These communal sleeping behaviors would have varied by species, with some maintaining tight-knit family groups while others formed larger, more fluid aggregations based on opportunity and environmental conditions.

Temperature Regulation During Sleep

Dinosaur sleeping locations were likely influenced by thermoregulatory needs, which would have varied significantly across different species and environments. Large dinosaurs, particularly massive sauropods, would have faced challenges dissipating body heat and might have sought open areas with better airflow during rest, especially in warm climates. Smaller species, conversely, would have needed to conserve heat during cool nights and might have selected sheltered locations or huddled together, using social thermoregulation strategies similar to modern birds. The discovery of feathers and feather-like structures in many dinosaur groups suggests these coverings played roles in both insulation and heat dissipation during rest periods. Seasonal migrations observed in some dinosaur populations might have been partly motivated by finding optimal sleeping environments as climate conditions changed. Fossil evidence from polar regions shows dinosaurs survived in areas with significant seasonal temperature variations, suggesting they had effective strategies for maintaining appropriate body temperatures during sleep throughout the year. The growing evidence for endothermy (warm-bloodedness) in many dinosaur groups further suggests they required specific environmental conditions for optimal rest, similar to modern mammals and birds.

Predator Avoidance Strategies During Rest

Dinosaurs developed sophisticated strategies to avoid predation during their vulnerable sleeping hours, with different approaches based on size, habitat, and social structure. Smaller species likely utilized camouflage and concealment, selecting sleeping locations that matched their coloration or provided physical hiding spots among vegetation or rock formations. Evidence of dinosaur coloration preserved in exceptional fossils suggests many species had patterns that would have provided effective camouflage when motionless. Sentinel systems, where certain individuals remain vigilant while others rest, were probably common in social species, similar to modern herd animals. Some dinosaurs may have selected sleeping locations with limited access points, such as cave entrances or dense thickets, allowing them to monitor potential approach routes for predators. Trackway evidence suggests many herbivorous dinosaurs traveled in mixed-age herds, which would have positioned more vulnerable juveniles in protected central positions during rest periods. For the largest dinosaurs, sheer size provided significant protection, though even they likely developed behavioral adaptations to minimize vulnerability during sleep, such as sleeping in positions that allowed for rapid rising or selecting terrain that gave them tactical advantages against potential threats.

Geographic Variations in Sleeping Habits

Dinosaur sleeping habits likely varied considerably across different geographic regions and ecosystems, reflecting adaptations to local conditions. Species inhabiting polar regions, where extended periods of darkness occur seasonally, would have needed different sleeping strategies compared to those living in more equatorial environments with consistent day-night cycles. Evidence from polar dinosaur fossils suggests some species remained in these extreme environments year-round, indicating they had developed effective resting strategies for the challenging conditions. Coastal dinosaurs might have selected sleeping locations that balanced access to marine food sources with protection from tides and coastal predators. Desert-dwelling species would have faced extreme temperature fluctuations between day and night, potentially seeking out thermally stable microhabitats for rest, such as burrows or shaded ravines. Mountainous environments would have presented different challenges, with evidence suggesting some dinosaur species migrated vertically with seasonal changes, selecting different elevation zones for optimal sleeping conditions throughout the year. These geographic variations in sleeping habits would have contributed to the remarkable adaptability that allowed dinosaurs to thrive across nearly all of Earth’s terrestrial environments for over 165 million years.

Modern Analogues: What Birds and Reptiles Tell Us

As the closest living relatives of dinosaurs, modern birds provide valuable insights into potential dinosaur sleeping behaviors, particularly for theropods. Many bird species exhibit unihemispheric sleep, where one brain hemisphere remains alert while the other rests, a trait that might have evolved in their dinosaur ancestors as a predator avoidance strategy. The discovery of dinosaurs preserved in bird-like sleeping postures strongly suggests this behavioral connection. Reptiles, representing the broader ancestral group from which dinosaurs evolved, display different sleep patterns characterized by shorter, more frequent sleep periods than birds or mammals, which might have been true for some dinosaur groups as well. Modern crocodilians, as the closest living relatives to both birds and dinosaurs, offer another comparative model with their ability to remain partially alert during rest. The communal roosting behaviors seen in many bird species, where individuals gather in large numbers for overnight safety, likely have roots in dinosaur behavior. The diverse sleep adaptations seen in modern animals occupying similar ecological niches to various dinosaur groups, from large grazing mammals to predatory birds, provide a framework for understanding how different dinosaur species might have balanced rest requirements with survival pressures.

Conclusion

The sleeping habits of dinosaurs, while not directly observable, can be reasonably inferred through a combination of fossil evidence, comparative anatomy, and ecological understanding. The diversity of dinosaur species suggests they employed a wide range of sleeping strategies—from the giant sauropods possibly resting in open plains to provide visibility against predators, to smaller theropods seeking the protection of forests or even sleeping in trees. Social species likely slept in groups, providing mutual protection, while others may have relied on camouflage or strategic positioning. As paleontology continues to advance with new fossil discoveries and analytical techniques, our understanding of dinosaur sleeping behavior will undoubtedly become more refined, adding another dimension to our knowledge of how these remarkable animals lived their daily lives across the Mesozoic era.