The vast, prehistoric landscapes of North America once thundered with the footsteps of magnificent dinosaurs that dominated the continent’s ecosystems. Among these ancient behemoths was Torosaurus, a spectacular horned dinosaur whose fossils have been unearthed in several states, including Wyoming. This remarkable creature, whose name means “perforated lizard,” has fascinated paleontologists since its discovery in the late 19th century. With its massive frilled skull and impressive horns, Torosaurus represents one of the most visually striking dinosaurs of the Late Cretaceous period, offering us a window into Wyoming’s prehistoric past and the diverse fauna that once called this region home.

The Discovery of Torosaurus

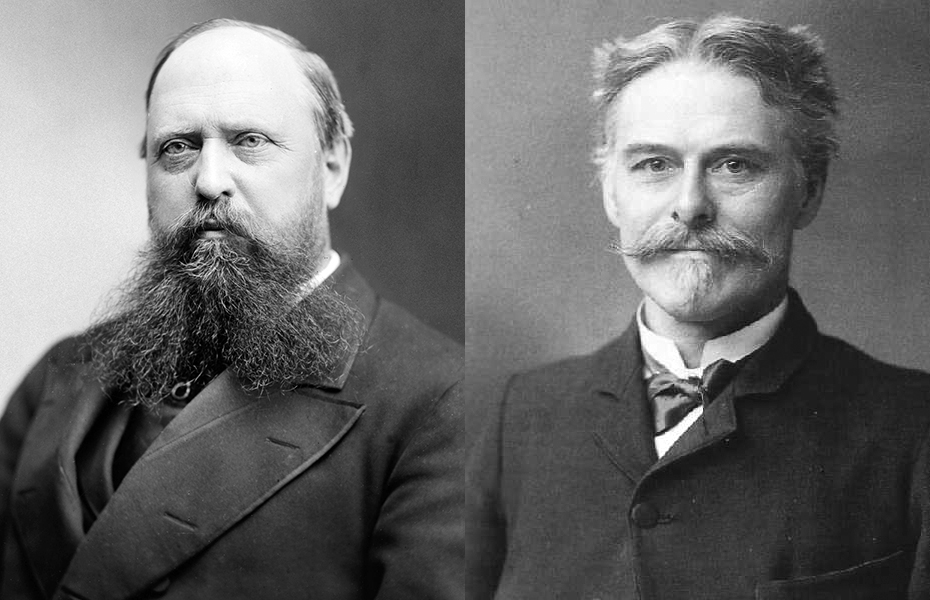

Torosaurus was first scientifically described in 1891 by the renowned paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh, during the competitive fossil-hunting period known as the “Bone Wars.” The initial specimens were discovered in Wyoming and neighboring states, providing science with the first glimpse of this magnificent creature. Marsh, who was a professor at Yale University, named the genus Torosaurus, meaning “perforated lizard” or “bull lizard,” referencing the large openings in its distinctive frill. Since these initial discoveries, multiple Torosaurus specimens have been excavated throughout the American West, with Wyoming remaining a particularly important site for these fossils. Each new discovery has added valuable pieces to our understanding of this creature’s anatomy and evolutionary history.

Physical Characteristics and Size

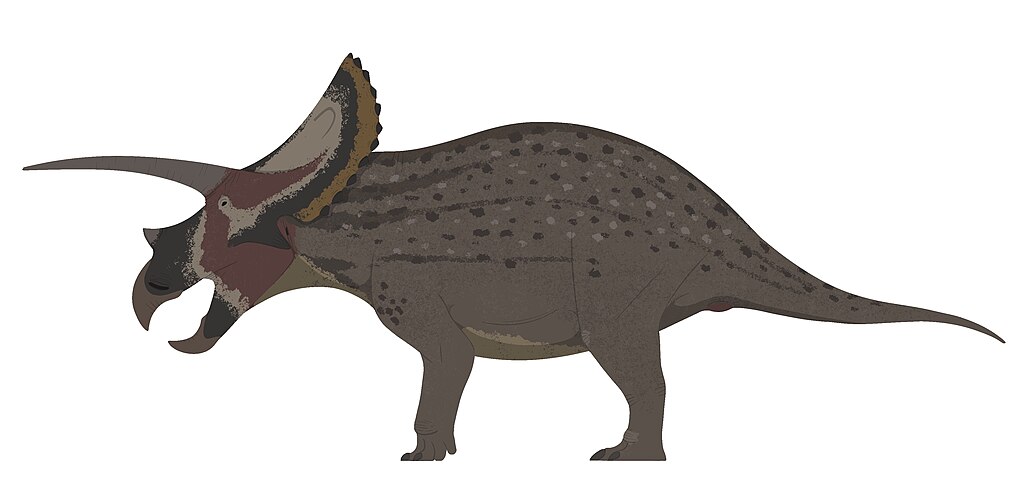

Torosaurus was truly a giant among its contemporaries, measuring approximately 25 feet (7.6 meters) in length and weighing an estimated 8 to 10 tons. Its most distinctive feature was undoubtedly its enormous skull, which could reach over 8 feet (2.5 meters) in length—one of the largest skulls of any land animal ever to exist. The skull was dominated by an expansive frill that extended backward from the head, featuring large fenestrae (openings) that likely reduced weight while maintaining structural integrity. Complementing this impressive headgear were two long, forward-facing brow horns that could extend up to 3 feet (1 meter) in length, along with a smaller horn on its snout. Its massive body was supported by four sturdy, column-like legs, while its tail was relatively short compared to other dinosaurs of similar size.

Geological Timeline: When Did Torosaurus Live?

Torosaurus inhabited North America during the Late Cretaceous period, specifically the Maastrichtian age, approximately 68 to 66 million years ago. This places these magnificent creatures among the last non-avian dinosaurs to walk the Earth before the catastrophic extinction event that marked the end of the Cretaceous period. During this time, Wyoming and much of western North America looked dramatically different than today. The region was part of a landmass called Laramidia, created when the Western Interior Seaway divided North America into eastern and western portions. The climate was warmer and more humid than modern Wyoming, supporting lush coastal plains and diverse ecosystems that provided ideal habitats for Torosaurus and its contemporaries.

The Wyoming Habitat of Torosaurus

During the Late Cretaceous, the Wyoming landscape that Torosaurus called home bore little resemblance to the state’s modern geography. Instead of the mountainous, relatively arid terrain we see today, prehistoric Wyoming featured extensive coastal lowlands and floodplains bordering the Western Interior Seaway. These environments were characterized by subtropical conditions with diverse vegetation, including coniferous forests, ferns, cycads, and early flowering plants. Extensive river systems crisscrossed these plains, creating rich riparian environments that supported a variety of life. This lush habitat provided Torosaurus with abundant food sources and nesting grounds, allowing these massive herbivores to thrive in large numbers across the region, leaving behind the fossils that paleontologists continue to unearth today.

Diet and Feeding Habits

As a member of the ceratopsid family, Torosaurus was an obligate herbivore with a specialized feeding apparatus perfectly adapted for processing tough plant material. Its powerful beak-like structure at the front of its mouth could snip through fibrous vegetation, while batteries of teeth arranged in dental batteries sheared and ground plant matter with remarkable efficiency. These teeth were constantly replaced throughout the dinosaur’s lifetime, ensuring it always had sharp cutting surfaces. Based on the height at which its head was carried, Torosaurus likely fed on low to medium-height vegetation, possibly including cycads, ferns, palms, and early flowering plants that dominated the Late Cretaceous landscape. Analysis of fossilized stomach contents and coprolites (fossilized dung) from related ceratopsians suggests these dinosaurs may have been selective feeders, targeting specific plant types rather than indiscriminately consuming all available vegetation.

The Function of the Distinctive Frill

The enormous frill that adorned Torosaurus’s skull has been the subject of extensive scientific debate regarding its primary function. While early paleontologists suggested it served primarily as defensive armor against predators like Tyrannosaurus rex, modern research proposes multiple purposes. The most widely accepted theory today suggests the frill functioned primarily as a display structure used in species recognition and sexual selection, similar to a peacock’s tail. The frill’s large size, distinctive shape, and potentially vivid coloration would have made for an impressive visual display during courtship rituals or competitive interactions between males. Additionally, the extensive blood vessel channels visible in well-preserved specimens indicate the frill may have served a thermoregulatory function, helping to regulate body temperature by dissipating excess heat or absorbing warmth. Some researchers also propose the frill provided anchor points for powerful jaw muscles, enhancing Torosaurus’s feeding capabilities.

Torosaurus vs. Triceratops: The Controversy

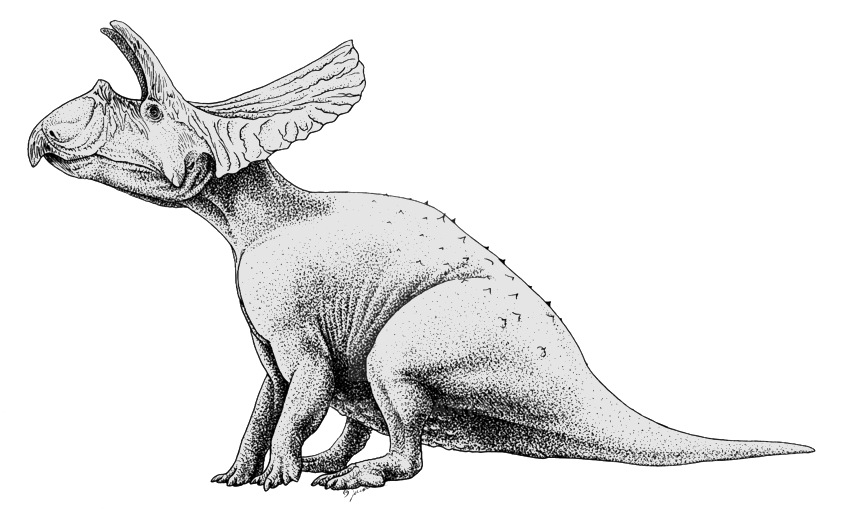

One of the most fascinating scientific debates in modern paleontology centers around the relationship between Torosaurus and the more famous Triceratops. In 2010, paleontologists John Scannella and Jack Horner proposed a controversial hypothesis suggesting that Torosaurus specimens might actually represent mature adult Triceratops rather than a distinct genus. According to their theory, as Triceratops aged, its solid frill expanded and developed the characteristic holes (fenestrae) seen in Torosaurus specimens. This hypothesis was based on histological studies of bone tissue that suggested a developmental relationship between the two forms. However, this remains highly contested, with many paleontologists arguing that significant anatomical differences beyond just the frill, along with the discovery of young Torosaurus specimens, support maintaining them as separate genera. The debate continues to stimulate important research into dinosaur growth patterns and the process of identifying distinct species in the fossil record.

Social Behavior and Herd Structure

While direct evidence of Torosaurus’s social behavior remains limited, paleontologists can make informed inferences based on fossil evidence and comparisons with related ceratopsians. Multiple specimens discovered in relative proximity suggest Torosaurus likely exhibited some degree of gregarious behavior, possibly living in loose herds for protection against predators and successful reproduction. Like modern herbivores such as elephants or bison, these herds may have been structured around family groups led by dominant individuals. The elaborate frills and horns likely played important roles in establishing dominance hierarchies and attracting mates, with larger, more impressive displays signaling genetic fitness. Some ceratopsian bonebeds containing multiple individuals of varying ages suggest these dinosaurs may have migrated seasonally across the Wyoming landscape in search of optimal feeding grounds, following patterns of plant growth and climate variations throughout the year.

Reproduction and Growth

The reproductive biology of Torosaurus, while not directly preserved in the fossil record, can be reasonably inferred from related ceratopsians for which more evidence exists. Like other dinosaurs, Torosaurus likely reproduced by laying eggs, potentially in communal nesting grounds where multiple females would deposit their clutches. Based on growth studies of related ceratopsians, scientists believe Torosaurus exhibited relatively rapid growth in its early years, gradually slowing as it approached adult size. The distinctive frill and horns would have developed progressively during adolescence, reaching their full impressive dimensions only in mature adults. This delayed development of display structures supports the theory that they played crucial roles in mating competitions and establishing social dominance. The complete growth cycle from hatchling to full adult size likely took at least a decade, representing a significant investment in each offspring’s development.

Predators and Defense Mechanisms

Despite its massive size, Torosaurus faced genuine threats from the apex predators of Late Cretaceous Wyoming, particularly from tyrannosaurids like Tyrannosaurus rex. These formidable carnivores possessed the bite force and hunting strategies necessary to target even the largest herbivores. To counter such threats, Torosaurus evolved multiple defensive adaptations beyond its sheer size. Its most obvious defenses were the imposing forward-facing horns that could potentially inflict serious damage on attacking predators. When threatened, Torosaurus likely adopted a defensive posture facing predators head-on to present its horned face as a deterrent. The herding behavior inferred from fossil evidence would have provided additional protection, with multiple adults potentially forming defensive formations around younger individuals. Some tooth marks discovered on ceratopsian fossils confirm that these dinosaurs were indeed targeted by large predators, though whether these represent successful predation or unsuccessful attacks remains uncertain.

Notable Wyoming Fossil Discoveries

Wyoming has yielded several significant Torosaurus specimens that have contributed substantially to our understanding of this genus. One of the most important discoveries came from Niobrara County in eastern Wyoming, where a well-preserved skull with its distinctive perforated frill was excavated from the Lance Formation. The University of Wyoming Geological Museum houses impressive Torosaurus material that provides visitors with a glimpse of this magnificent creature. Another notable discovery from Wyoming’s Lance Formation included associated postcranial material that helped paleontologists better understand the overall body proportions and stance of Torosaurus. These Wyoming specimens are particularly valuable because they represent some of the most complete Torosaurus material ever found, allowing for more accurate reconstructions and comparative studies with other ceratopsians. Each new discovery from Wyoming’s fossil-rich formations continues to refine our picture of this remarkable dinosaur.

Extinction and Legacy

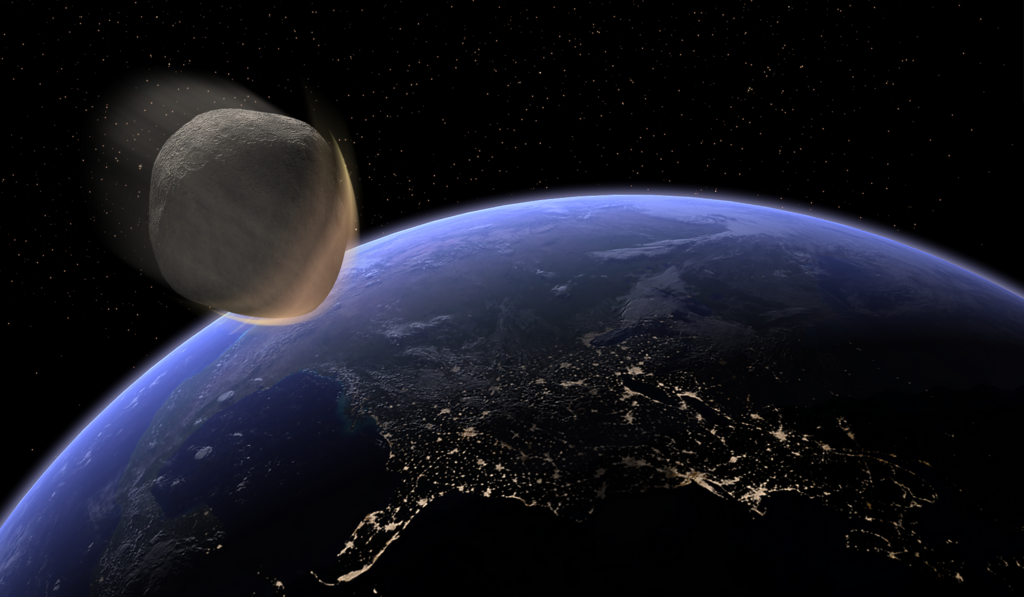

Torosaurus vanished from Earth approximately 66 million years ago as part of the mass extinction event that marked the end of the Mesozoic Era. This catastrophic event, likely triggered by a massive asteroid impact combined with intense volcanic activity, eliminated all non-avian dinosaurs along with approximately 75% of all species on Earth. As one of the last dinosaur species to exist before this extinction, Torosaurus represents the pinnacle of ceratopsian evolution—the culmination of millions of years of evolutionary refinement that produced one of the most specialized herbivores ever to walk the planet. Though Torosaurus itself left no descendants, its legacy lives on in scientific research and public imagination. The study of these magnificent creatures continues to provide valuable insights into dinosaur biology, ecosystem dynamics, and evolutionary processes, while their impressive appearance ensures they remain favorites in museum exhibits and dinosaur media.

Torosaurus in Popular Culture and Education

While less widely recognized than its cousin Triceratops, Torosaurus has nevertheless made notable appearances in paleontological education and popular media. The distinctive appearance of this massive horned dinosaur makes it a striking subject for museum displays, with reconstructions and models featured in major natural history museums around the world, including displays highlighting Wyoming’s prehistoric past. Educational programs throughout Wyoming often highlight Torosaurus as part of the state’s rich paleontological heritage, using these impressive dinosaurs to spark interest in science among young students. In popular culture, Torosaurus has appeared in various dinosaur documentaries, books, and toy lines, though often overshadowed by more famous ceratopsians. The ongoing scientific debate about its relationship to Triceratops has also generated public interest, demonstrating how paleontology remains a dynamic, evolving science rather than a field with all questions answered.

Current Research and Future Discoveries

Paleontological research on Torosaurus continues to evolve as new techniques and discoveries enhance our understanding of this magnificent creature. Modern methods such as CT scanning, histological analysis of bone microstructure, and geometric morphometrics are being applied to existing specimens, revealing details about growth patterns, sensory capabilities, and potential sexual dimorphism that were previously inaccessible. Wyoming remains at the forefront of ceratopsian research, with ongoing field expeditions regularly uncovering new material from the state’s fossil-rich formations. The continued exploration of the Lance Formation and other Late Cretaceous deposits holds promise for future Torosaurus discoveries that may help resolve the taxonomic debate surrounding this genus. Additionally, new analytical approaches to existing specimens, including stable isotope analysis of teeth to determine diet and habitat preferences, are providing ever more detailed reconstructions of how these magnificent animals lived in prehistoric Wyoming.

The story of Torosaurus is far from complete, with each new discovery and analytical technique adding detail to our understanding of these magnificent horned giants. From the rugged badlands of Wyoming emerges a picture of a specialized herbivore that represented the pinnacle of ceratopsian evolution—a true testament to the diversity and wonder of dinosaur life in North America’s final prehistoric chapter. As science advances and new specimens emerge from Wyoming’s fossil beds, we can look forward to an ever more complete understanding of Torosaurus and its place in the spectacular ecosystem it once dominated.