Picture walking into a dimly lit hall in the 1800s, where dusty glass cases held mysterious fragments of bone and strange fossils that no one could properly explain. This was the reality of natural history museums before dinosaurs burst onto the scene and revolutionized everything we thought we knew about our planet’s past. The discovery of these ancient giants didn’t just add new exhibits to museum collections—it completely transformed how we understand life on Earth and forever changed the way museums present the natural world to the public.

The World Before Dinosaur Discoveries

Before the first dinosaur fossils were properly identified, natural history museums were quite different places than what we know today. These institutions primarily focused on displaying rocks, minerals, and the occasional strange fossil that scholars couldn’t quite categorize. Visitors would walk through halls filled with geological specimens and curiosities, but there was no grand narrative connecting these objects to a larger story about Earth’s history. The concept of deep time—the idea that our planet was millions of years old—was still controversial, and most people believed the Earth was only a few thousand years old. Museums reflected this limited understanding, presenting collections that seemed disconnected from any overarching theme about life’s evolution and the planet’s ancient past.

William Buckland’s Revolutionary Megalosaurus Discovery

Everything began to change when William Buckland, a geology professor at Oxford University, made a discovery that would shake the scientific world to its core. In 1824, he formally described Megalosaurus based on fossil remains found in English quarries, becoming the first person to scientifically name a dinosaur. What made this discovery so shocking wasn’t just the size of the creature—estimated to be over 30 feet long—but the fact that it represented something entirely unknown to science. Buckland’s careful analysis revealed that this wasn’t just another large lizard or crocodile, but something fundamentally different from any living animal. This single discovery forced museums to reconsider their entire approach to displaying fossils, as they now had evidence of creatures that challenged everything people thought they knew about the history of life on Earth.

Gideon Mantell and the Iguanodon Sensation

Just a year after Buckland’s announcement, Gideon Mantell made another earth-shattering discovery that would further transform museum displays forever. When Mantell described Iguanodon in 1825, based on teeth found by his wife Mary Ann in Sussex, he painted a picture of a massive herbivorous reptile unlike anything in the modern world. The discovery was particularly fascinating because it showed that these ancient giants weren’t all fearsome predators—some were peaceful plant-eaters that roamed primeval forests. Museums quickly realized they needed to completely rethink their fossil displays, as these discoveries suggested an entire lost world of creatures that had once dominated the Earth. The public’s fascination with Iguanodon was immediate and intense, forcing museums to create special exhibitions just to accommodate the crowds of curious visitors who wanted to see evidence of these prehistoric monsters.

Richard Owen Coins the Term “Dinosauria”

The man who would forever change how we think about these ancient creatures was Richard Owen, a brilliant anatomist who realized that Megalosaurus, Iguanodon, and other similar fossils represented something entirely new to science. In 1842, Owen coined the term “Dinosauria,” meaning “terrible lizards,” and established that these weren’t just oversized versions of modern reptiles—they were a completely distinct group of animals. His work provided museums with a scientific framework for organizing and displaying these fossils, giving them a proper name and classification system. Owen’s influence extended far beyond naming; he revolutionized how museums presented paleontological specimens by emphasizing the need for accurate reconstructions and scientific rigor. This approach transformed museums from mere curiosity shops into serious educational institutions that could tell the story of life’s evolution through carefully curated displays.

The Crystal Palace Dinosaurs Create Public Hysteria

Nothing could have prepared the Victorian public for what Richard Owen and sculptor Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins created at Crystal Palace in 1854. These life-sized concrete dinosaur sculptures represented the first time anyone had attempted to show what these creatures might have looked like when they were alive, and the result was absolutely sensational. Thousands of people flocked to see these prehistoric beasts, which looked quite different from how we imagine dinosaurs today—the Iguanodon was depicted as a massive, rhinoceros-like creature with a horn on its nose. The sculptures were so popular that they sparked what historians now call “dinomania,” a public obsession with prehistoric life that forced museums worldwide to scramble to acquire their own dinosaur fossils. This marked the beginning of museums as entertainment destinations, not just scholarly institutions, as they realized that dinosaurs could draw massive crowds and capture the public imagination like nothing else.

American Fossil Hunters Enter the Scene

While British scientists were making groundbreaking discoveries, American paleontologists were about to unleash an even more dramatic revolution in museum displays. The vast Western territories of the United States contained fossil deposits that dwarfed anything found in Europe, and discoveries like Joseph Leidy’s Hadrosaurus in 1858 proved that America was a treasure trove of prehistoric life. What made American discoveries so significant was their completeness—while European finds were often fragmentary, American fossils included nearly complete skeletons that allowed for much more accurate reconstructions. Museums on both sides of the Atlantic began competing fiercely to acquire these spectacular specimens, leading to the development of professional fossil-hunting expeditions and museum-sponsored excavations. This competitive atmosphere pushed museums to constantly expand their paleontology departments and create ever more impressive displays to outdo their rivals.

The Great Bone Wars Transform Museum Competition

The rivalry between paleontologists Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope, known as the “Bone Wars,” turned museum collecting into a full-contact sport that forever changed how institutions acquired specimens. These two men spent decades trying to outdo each other, discovering dozens of new dinosaur species and shipping countless fossils back to their respective institutions—Marsh to Yale’s Peabody Museum and Cope to various museums including the American Museum of Natural History. Their bitter competition led to some of the most spectacular dinosaur discoveries ever made, including Allosaurus, Stegosaurus, and Triceratops, but it also established a new model for museum expeditions. Museums realized they couldn’t rely on casual collecting anymore; they needed dedicated teams of fossil hunters, proper funding for expeditions, and sophisticated preparation facilities to clean and mount their discoveries. This professionalization of paleontology transformed museums from passive repositories into active research institutions that generated their own groundbreaking discoveries.

Complete Skeletons Revolutionize Display Methods

The discovery of complete dinosaur skeletons marked a turning point in how museums could present these ancient creatures to the public. Instead of displaying isolated bones and teeth in glass cases, museums could now mount entire skeletons in dynamic poses that brought these creatures to life in visitors’ imaginations. The first mounted dinosaur skeleton, Hadrosaurus, was displayed at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia in 1868, and it created an absolute sensation among visitors who had never seen anything like it before. Museums quickly realized that these mounted skeletons were their most powerful educational tools, capable of conveying the size, structure, and majesty of these ancient beasts in ways that individual bones never could. This led to the development of new techniques for preparing, mounting, and displaying fossils, turning museum preparators into skilled artisans who could create scientifically accurate yet visually stunning exhibits.

Museums Become Centers of Scientific Research

As dinosaur discoveries multiplied, museums transformed from simple display spaces into major centers of scientific research and discovery. Institutions like the American Museum of Natural History and the Smithsonian began hiring full-time paleontologists, establishing research laboratories, and funding their own fossil-hunting expeditions to remote locations around the world. This shift meant that museums were no longer just places where scientists displayed their findings—they became places where groundbreaking research actually happened. The presence of world-class researchers attracted students, visiting scholars, and international collaborations that elevated these institutions to the forefront of scientific discovery. Museums began publishing their own research journals, hosting scientific conferences, and becoming recognized authorities on paleontology and evolution, fundamentally changing their role in the scientific community.

Public Education Takes on New Dimensions

Dinosaur discoveries forced museums to completely rethink their educational mission, as these creatures provided a perfect gateway for teaching complex scientific concepts to the general public. Museums realized that dinosaurs could be used to explain evolution, geological time, extinction, and the scientific method in ways that were both accessible and fascinating to visitors of all ages. Educational programs expanded dramatically, with museums offering guided tours, lectures, and hands-on activities centered around their dinosaur collections. The development of museum education departments became a priority, as institutions recognized that their dinosaur displays could inspire the next generation of scientists and create lifelong learners who would support scientific research. This educational focus transformed museums from elite institutions serving primarily scholars into community resources that welcomed and served diverse audiences.

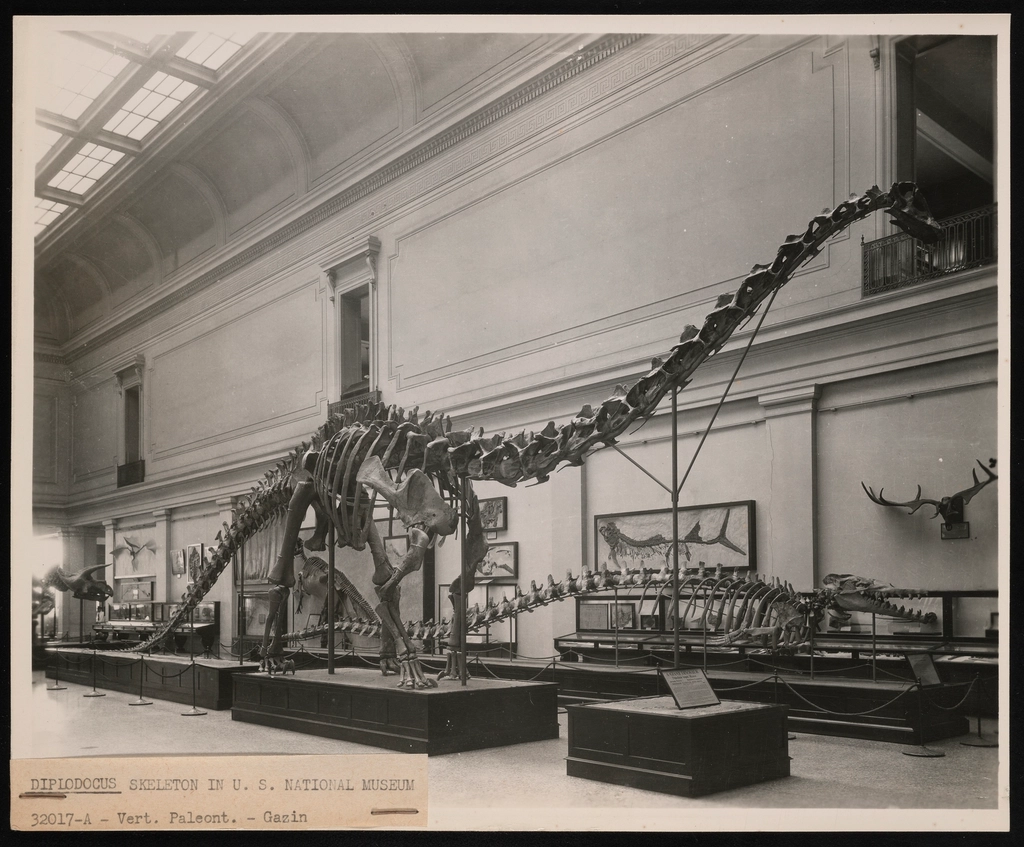

Architectural Changes Accommodate Giant Displays

The sheer size of dinosaur skeletons forced museums to completely redesign their buildings and exhibition spaces to accommodate these massive displays. Traditional museum halls with low ceilings and small rooms were suddenly inadequate for housing creatures that could reach heights of 40 feet or more and stretch over 80 feet in length. Museums began constructing soaring cathedral-like halls specifically designed to showcase their dinosaur collections, with high ceilings, reinforced floors, and dramatic lighting that could properly display these ancient giants. The architecture itself became part of the visitor experience, creating a sense of awe and wonder that complemented the scientific significance of the specimens. These grand dinosaur halls became the centerpieces of museums, often serving as the main entrance galleries that greeted visitors and set the tone for their entire museum experience.

International Collaboration and Competition

Dinosaur discoveries sparked an unprecedented level of international collaboration and competition among museums worldwide, as institutions realized that no single country had a monopoly on these fascinating creatures. Museums began trading specimens, sharing research, and collaborating on expeditions to fossil-rich locations around the globe, creating a network of scientific exchange that continues today. At the same time, national pride became attached to dinosaur discoveries, with countries competing to have the most impressive specimens and the most complete collections in their national museums. This combination of cooperation and competition drove museums to constantly improve their standards, invest more resources in paleontology, and push the boundaries of what was possible in terms of fossil preparation and display. The result was a global elevation in museum quality and scientific rigor that benefited institutions and visitors everywhere.

Technology and Preparation Techniques Advance

The challenge of extracting, preparing, and displaying dinosaur fossils pushed museums to develop increasingly sophisticated techniques and technologies that revolutionized the entire field of paleontology. Museums invested in specialized tools, chemical treatments, and preparation methods that could safely remove fossils from surrounding rock and preserve them for study and display. The development of pneumatic tools, acid baths, and precision instruments allowed preparators to reveal details in fossils that had never been seen before, leading to new discoveries about dinosaur anatomy and behavior. Museums also pioneered new mounting techniques that could support the enormous weight of complete dinosaur skeletons while presenting them in lifelike poses that captivated visitors. These technical advances not only improved museum displays but also contributed to the broader scientific understanding of these ancient creatures.

The Legacy Lives On in Modern Museums

The transformation that began with those first dinosaur discoveries in the 1820s continues to shape natural history museums today, as these institutions remain at the forefront of paleontological research and public education. Modern museums still build their reputations on their dinosaur collections, using cutting-edge technology like CT scanning, 3D printing, and virtual reality to present these creatures in ways that Victorian visitors could never have imagined. The fundamental principles established during the early days of dinosaur discovery—rigorous scientific research, engaging public displays, and educational outreach—remain the foundation of museum work today. Museums continue to sponsor fossil-hunting expeditions, discover new species, and use dinosaurs as gateways to teach visitors about science, evolution, and the natural world. The excitement and wonder that dinosaurs generate in museum visitors today is the same emotion that drew crowds to those first displays over 150 years ago, proving that some discoveries are so profound they continue to inspire generation after generation.

Conclusion

Those early dinosaur discoveries didn’t just change what museums displayed—they fundamentally transformed these institutions into the dynamic centers of learning and discovery we know today. From Richard Owen’s first scientific descriptions to the mounted skeletons that now dominate museum halls worldwide, dinosaurs forced museums to evolve from simple curiosity cabinets into sophisticated research institutions that continue to unlock the secrets of our planet’s ancient past. What started with a few mysterious bones in English quarries ultimately revolutionized how we understand life on Earth and created the modern natural history museum experience that continues to inspire millions of visitors every year.