When we imagine dinosaurs, many of us picture ferocious predators with razor-sharp teeth and powerful jaws chasing prey across prehistoric landscapes. While not all dinosaurs were aggressive hunters, paleontological evidence has revealed several species that possessed remarkable adaptations for attack and combat. This article explores the most aggressive dinosaur species ever discovered, examining their hunting strategies, physical adaptations, and the evidence that points to their formidable nature. From well-known predators to lesser-known but equally fearsome hunters, these dinosaurs represent the apex of prehistoric aggression.

Tyrannosaurus Rex: The Ultimate Apex Predator

No discussion of aggressive dinosaurs would be complete without Tyrannosaurus rex, perhaps the most famous predator to ever walk the Earth. Standing up to 40 feet long and weighing up to 9 tons, T. rex possessed a bite force estimated at 12,800 pounds, the strongest of any land animal ever to exist. Recent research suggests T. rex could crush bones with ease, allowing it to extract nutritious marrow from its prey—a feeding strategy called osteophagy. Fossil evidence, including T. rex teeth embedded in the bones of other dinosaurs and healed bite marks on other T. rex specimens, points to an animal that actively hunted large prey and engaged in fierce combat with members of its own species. Perhaps most telling of its aggressive nature is its forward-facing eyes providing binocular vision—an adaptation typically seen in active predators rather than scavengers.

Spinosaurus: The Aquatic Assassin

Spinosaurus aegyptiacus has recently been recognized as one of history’s most specialized and aggressive dinosaur predators. At up to 50 feet in length, it was larger than T. rex and uniquely adapted for hunting in aquatic environments with its paddle-like tail, dense bones, and crocodile-like snout filled with conical teeth perfect for catching slippery prey. Fossil evidence indicates Spinosaurus actively preyed upon car-sized fish, sharks, and possibly other dinosaurs that ventured too close to waterways. Its semi-aquatic lifestyle represented a unique hunting strategy among large theropods, allowing it to exploit food resources unavailable to purely terrestrial predators. Recent discoveries suggest Spinosaurus may have been primarily aquatic, making it the first known swimming dinosaur and a fearsome ambush predator in prehistoric rivers and coastal environments.

Utahraptor: The Ultimate Pack Hunter

The largest confirmed dromaeosaur (raptor) dinosaur, Utahraptor ostrommaysi, represents one of the most efficient killing machines of the Early Cretaceous period. Growing up to 23 feet long and weighing over 1,100 pounds, Utahraptor possessed a 9-inch sickle-shaped claw on each foot that could deliver devastating slashing attacks. Fossil evidence suggests these massive raptors hunted in coordinated packs, allowing them to take down prey much larger than themselves, including the massive Iguanodon. One remarkable fossil discovery dubbed the “Utahraptor Death Trap” captured multiple Utahraptors apparently caught while attacking prey mired in quicksand, providing tangible evidence of their pack-hunting behavior. Their bird-like agility combined with mammal-like intelligence and pack tactics would have made Utahraptor encounters virtually unsurvivable for prey animals.

Allosaurus: The Glass-Jawed Guillotine

Allosaurus fragilis dominated the Late Jurassic landscape as North America’s apex predator 150 million years ago. Growing up to 33 feet long, this theropod employed a unique hunting strategy compared to later predators like T. rex. Rather than relying on crushing bite force, Allosaurus used its skull like a hatchet, opening its jaws extremely wide and bringing the top of its mouth down with tremendous force, using serrated teeth to slice through flesh. Fossil evidence, including an Allosaurus skeleton found with a Stegosaurus tail spike embedded in its pubic bone, demonstrates these predators engaged in high-risk attacks on dangerous, well-armed prey. Studies of Allosaurus skulls show extremely high rates of injury and healing, suggesting these dinosaurs regularly engaged in violent encounters both when hunting and during territorial or mating conflicts with their own kind.

Dakotaraptor: The Mid-Sized Menace

Dakotaraptor steini represents a particularly aggressive raptor species that inhabited North America during the Late Cretaceous period approximately 66 million years ago. At roughly 16-18 feet long, Dakotaraptor filled a crucial ecological niche between smaller raptors like Velociraptor and larger tyrannosaurids. What made Dakotaraptor especially dangerous was its combination of size and speed—large enough to take down substantial prey but still agile enough to pursue fast-moving targets. Skeletal evidence reveals Dakotaraptor possessed “quill knobs” on its forearms, indicating it had feathers, which may have been used in display behaviors or to assist in stabilizing the animal during attacks. Its large, curved foot claws could disembowel prey with a single kick, while forearms adapted for grasping would have allowed it to hold struggling victims. These adaptations point to an animal evolved specifically for aggressive predation.

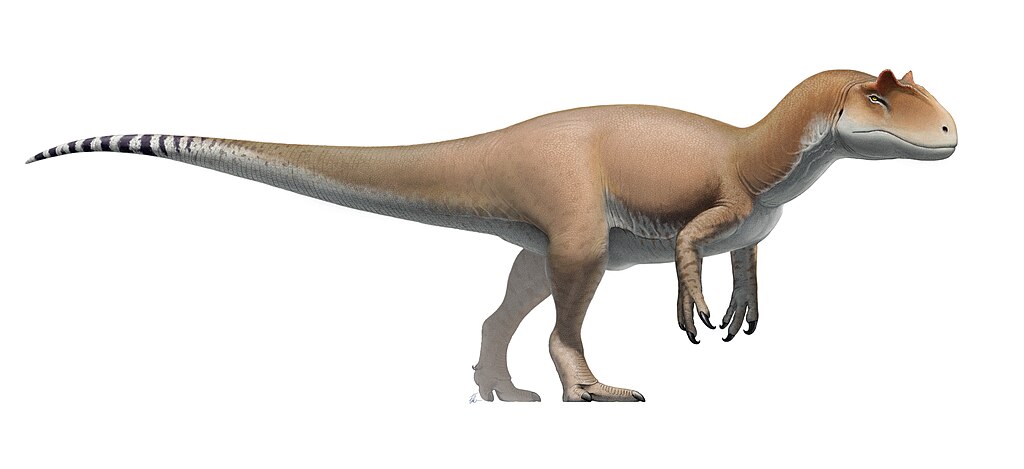

Giganotosaurus: The T. rex Rival

Giganotosaurus carolinii may have been the largest carnivorous dinosaur to walk on land, slightly outmeasuring even Tyrannosaurus rex in length at approximately 43 feet. This enormous theropod roamed Argentina during the mid-Cretaceous period about 98 million years ago, hunting in an ecosystem dominated by some of the largest sauropods ever discovered. Unlike the bone-crushing T. rex, Giganotosaurus had a longer, narrower skull with blade-like teeth specialized for slicing rather than crushing, suggesting it employed slashing attacks to weaken larger prey through blood loss. Fossil evidence indicates these massive predators may have hunted Argentinosaurus, a sauropod that reached lengths of over 100 feet, possibly using pack tactics to bring down such enormous prey. The front-heavy build of Giganotosaurus, with powerful legs and a massive skull balanced by a stiffened tail, points to an animal adapted for launching devastating initial attacks rather than prolonged chases.

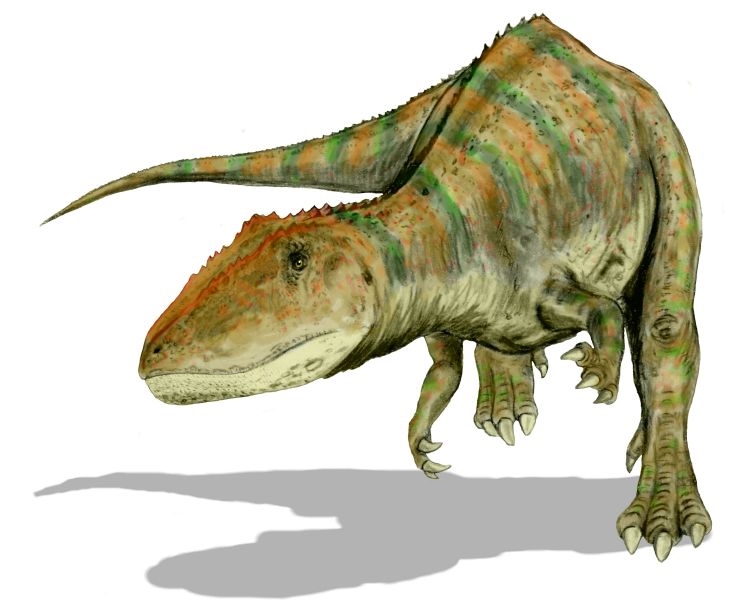

Carcharodontosaurus: The Shark-Toothed Killer

Carcharodontosaurus saharicus, whose name means “shark-toothed lizard,” was one of North Africa’s most formidable predators during the mid-Cretaceous period around 100 million years ago. Growing to approximately 44 feet in length and weighing up to 8 tons, this massive theropod possessed teeth that closely resembled those of great white sharks—serrated, blade-like, and up to 8 inches long. These teeth were designed not for crushing bone but for slicing through flesh and causing catastrophic blood loss in prey. Skull analysis indicates Carcharodontosaurus had some of the longest skull measurements of any theropod dinosaur, housing powerful jaw muscles that could deliver devastating bites. Fossil evidence suggests these predators shared their ecosystem with Spinosaurus and likely competed for territory and prey, potentially engaging in aggressive interactions with these other apex predators. Their specialized dentition and massive size point to an animal that evolved specifically for aggressive predation on large dinosaurs.

Mapusaurus: The Social Super-Predator

Mapusaurus roseae represents one of the clearest examples of social predation among large theropod dinosaurs. Discovered in Argentina in bone beds containing multiple individuals of varying ages, this 40-foot carnivore appears to have lived and hunted in family groups or packs. This social behavior would have allowed these massive predators to take down prey that would be impossible for a solitary hunter, including the immense sauropod Argentinosaurus. Fossil evidence shows specialized teeth and jaws adapted for slicing through tough hide and flesh rather than crushing bone, suggesting Mapusaurus employed a strategy of inflicting multiple wounds to weaken larger prey through blood loss and shock. Their proportionally long legs indicate these were pursuit predators capable of sustained chases, unlike the more ambush-oriented tyrannosaurs. The combination of pack hunting behavior, massive size, and specialized killing adaptations makes Mapusaurus one of history’s most formidable predatory dinosaurs.

Carnotaurus: The Horned Sprinter

Carnotaurus sastrei stands out among theropods for its distinctive pair of horns above its eyes and extraordinarily tiny arms, even smaller proportionally than those of T. rex. At around 30 feet long, this Late Cretaceous predator from Argentina possessed several unique adaptations that made it a singularly aggressive hunter. Most notably, skeletal analysis indicates Carnotaurus had exceptionally powerful legs and tail muscles that likely made it one of the fastest large theropods, capable of explosive acceleration when attacking prey. An exceptionally well-preserved specimen revealed Carnotaurus had a flexible neck with powerful muscles that would allow it to deliver devastating strikes with its reinforced skull and horns. Its unusual skull design featured interlocking jaw joints that distributed bite force along the entire jaw rather than concentrating it at the back, allowing for a more secure grip on struggling prey. These adaptations point to an animal that relied on high-speed ambush attacks followed by powerful bites to quickly dispatch victims.

Majungasaurus: The Cannibal King

Majungasaurus crenatissimus provides some of the strongest evidence for cannibalism among dinosaurs, making it a candidate for one of the most aggressive species ever discovered. This 23-foot theropod lived in Madagascar during the Late Cretaceous period, approximately 70 million years ago, as the apex predator in an isolated island ecosystem. Fossil evidence, including Majungasaurus bones bearing distinctive tooth marks that match Majungasaurus’s own dentition, strongly suggests these animals routinely preyed upon members of their own species. Its unusually short, robust skull housed teeth designed for delivering powerful, bone-crushing bites rather than the slicing action seen in many other large theropods. Recent studies of Majungasaurus growth patterns indicate these dinosaurs grew rapidly to adult size, suggesting a high-competition environment where quick development provided survival advantages. The combination of cannibalistic behavior, powerful bite mechanics, and rapid growth points to an extraordinarily aggressive lifestyle even by theropod standards.

Deinonychus: The Terrible Claw

Deinonychus antirrhopus revolutionized our understanding of dinosaur behavior when its fossils were discovered alongside those of the larger herbivore Tenontosaurus in arrangements suggesting pack hunting behavior. These 10-foot-long dromaeosaurs possessed the classic “raptor” features that would later capture public imagination: sickle-shaped claws on their feet, grasping hands with sharp talons, and a lithe, agile build. Biomechanical analysis indicates Deinonychus had remarkable grasping strength in its arms and could use its famous sickle claw to deliver deep, slashing wounds after leaping onto larger prey. Fossil evidence shows multiple Deinonychus often died alongside single larger prey animals, strongly suggesting coordinated pack attacks on dangerous herbivores many times their size. Their large brain cases indicate advanced intelligence, likely used for complex social interactions and hunting strategies. These adaptations made Deinonychus extraordinarily aggressive predators that could successfully attack animals many times their own weight through coordinated team tactics.

Tarbosaurus: The Asian Tyrant

Tarbosaurus bataar, sometimes called “Asia’s T. rex,” ruled the ecosystems of Mongolia and China during the Late Cretaceous period approximately 70 million years ago. Growing to nearly 40 feet long, this theropod shared many characteristics with its North American cousin, including massive jaws lined with banana-sized teeth capable of crushing bone. Unique to Tarbosaurus was a skull structure with less flexibility than T. rex but potentially greater bite stability, suggesting these predators specialized in delivering powerful, bone-crushing bites to quickly dispatch prey. Fossil evidence, including specimens with healed bite wounds matching Tarbosaurus teeth, indicates these animals engaged in violent confrontations with their own kind, likely over territory or mating rights. Unlike some other tyrannosaurids, Tarbosaurus had proportionally smaller arms, suggesting even greater specialization toward its powerful bite as its primary weapon. The combination of enormous size, specialized bone-crushing abilities, and evidence of intraspecific combat marks Tarbosaurus as one of history’s most aggressive dinosaur species.

Evidence of Dinosaur Aggression in the Fossil Record

Understanding dinosaur aggression requires careful interpretation of fossil evidence beyond just anatomy. One of the most compelling indicators comes from bite marks found on fossil bones that match specific predator dentition, such as distinctive T. rex tooth punctures in Triceratops frills. Healed injuries in prey species, like a Edmontosaurus with a partially healed T. rex bite to its tail, demonstrate active predation rather than scavenging. Perhaps most telling are signs of combat between members of the same species, evident in tyrannosaur specimens with facial bite marks that match their own dental profile. Bone beds containing multiple predator individuals alongside single prey specimens strongly suggest pack hunting behavior among species like Deinonychus and Mapusaurus. Trackways occasionally preserve evidence of pursuit or attack scenarios, though these rare finds remain limited. Together, these lines of evidence allow paleontologists to reconstruct the aggressive behaviors of animals that vanished millions of years ago, revealing dinosaurs not as mindless monsters but as sophisticated predators with complex hunting strategies.

Conclusion

The most aggressive dinosaur species developed remarkable adaptations for predation and combat during their millions of years of evolution. From the bone-crushing bite of Tyrannosaurus to the pack-hunting strategies of Utahraptor, these formidable predators represented the pinnacle of prehistoric aggression. Their specialized anatomy—including serrated teeth, massive jaws, slashing claws, and powerful limbs—enabled them to pursue, capture, and dispatch prey with terrifying efficiency. As paleontologists continue to uncover new fossils and apply advanced technologies to understand dinosaur biomechanics and behavior, our understanding of these aggressive species continues to evolve. What remains clear is that the dinosaur era witnessed the development of some of the most perfectly adapted predators in Earth’s history, animals whose aggressive capabilities still capture our imagination millions of years after their extinction.