Picture this: a massive asteroid hurtling through space at 40,000 miles per hour, carrying the energy of billions of atomic bombs. Now imagine a single dinosaur, going about its daily routine 66 million years ago, completely unaware that in mere hours, its world would end forever. This isn’t science fiction—it’s the incredible true story of fossil discoveries that have captured the exact moment when the age of dinosaurs came to a catastrophic close.

The Day the World Changed Forever

The Chicxulub impact wasn’t just another bad day for dinosaurs—it was the ultimate game-changer that rewrote Earth’s entire biological story. When that six-mile-wide asteroid slammed into what is now Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula, it unleashed forces that make our most powerful nuclear weapons look like firecrackers.

The sheer violence of this cosmic collision created a crater 93 miles wide and sent shockwaves rippling across the planet at speeds that defied imagination. Within minutes, the impact triggered earthquakes more powerful than anything in recorded human history, while tsunamis hundreds of feet high raced across ancient seas.

What makes this event truly mind-boggling is how it preserved its victims in real-time, creating fossil snapshots that tell the story of Earth’s most dramatic day. These aren’t just bones scattered by time—they’re entire ecosystems caught in the act of dying, preserved with stunning detail that still takes scientists’ breath away.

The Tanis Site: A Prehistoric Crime Scene

In the badlands of North Dakota lies perhaps the most extraordinary fossil site ever discovered—a place called Tanis that reads like a prehistoric crime scene frozen in amber. This remarkable location has yielded fossils that died not over millions of years, but within hours of the asteroid impact that ended the Cretaceous period.

The site preserves what scientists call a “death assemblage”—a collection of creatures that all perished simultaneously when the impact’s effects reached North America. Fish are found with tiny glass spherules in their gills, the same spherules that rained down from the sky as the asteroid vaporized upon impact.

What sets Tanis apart isn’t just what died there, but how they died. The fossils show animals in their final moments—some appear to have been caught mid-swim, others mid-stride. It’s as if someone hit pause on an entire ecosystem, preserving behaviors and interactions that would normally be lost to time.

Glass Spherules: Tiny Time Capsules

Among the most compelling evidence at Tanis are countless tiny glass spherules—microscopic beads that formed when the asteroid impact melted rock and hurled it into the atmosphere. These spherules, no bigger than grains of sand, tell an incredible story of destruction and preservation.

When the asteroid hit, temperatures at the impact site reached over 10,000 degrees Celsius, instantly vaporizing rock and creating a fireball that expanded outward. As molten material was ejected into space, it cooled and solidified into these glass beads, which then rained down across North America like deadly hail.

The spherules found at Tanis match perfectly with those from the Chicxulub crater, providing undeniable proof that these animals died on the very day of the impact. Fish fossils have been found with these glass beads literally embedded in their gills, showing they were breathing this apocalyptic fallout as they died.

The Fish That Gasped Its Last Breath

Perhaps no discovery at Tanis is more haunting than the perfectly preserved fish that appear to have died while literally breathing in the impact debris. These ancient paddlefish and sturgeon were found with their mouths agape, their gills packed with the telltale glass spherules that rained from the sky.

The positioning of these fish tells a story of desperation and confusion. Some appear to have been swimming frantically, perhaps trying to escape waters that were suddenly filled with debris and possibly boiling from seismic activity. Their final moments are written in stone with devastating clarity.

What makes these fish fossils extraordinary is their three-dimensional preservation. Unlike most fossils that are flattened over time, these specimens retain their original body shapes, allowing scientists to study their internal organs and even analyze their last meals. It’s forensic paleontology at its most dramatic.

Seismic Waves Recorded in Stone

The sediment layers at Tanis read like a seismograph made of stone, recording the exact sequence of catastrophic events that followed the asteroid impact. These layers show how massive seismic waves—some triggered by the impact itself—shook the earth with unprecedented violence.

Scientists have identified at least four separate seismic events recorded in these sediments, each one powerful enough to trigger massive underwater landslides and standing waves. The waves were so intense they created underwater “tsunamis” in inland lakes and rivers, tossing fish and other creatures about like toys.

The sediment also preserves evidence of “seiche” waves—standing waves that slosh back and forth in enclosed bodies of water like water in a bathtub. These waves, some reaching heights of several feet, repeatedly buried and uncovered dying animals, creating the perfect conditions for exceptional fossil preservation.

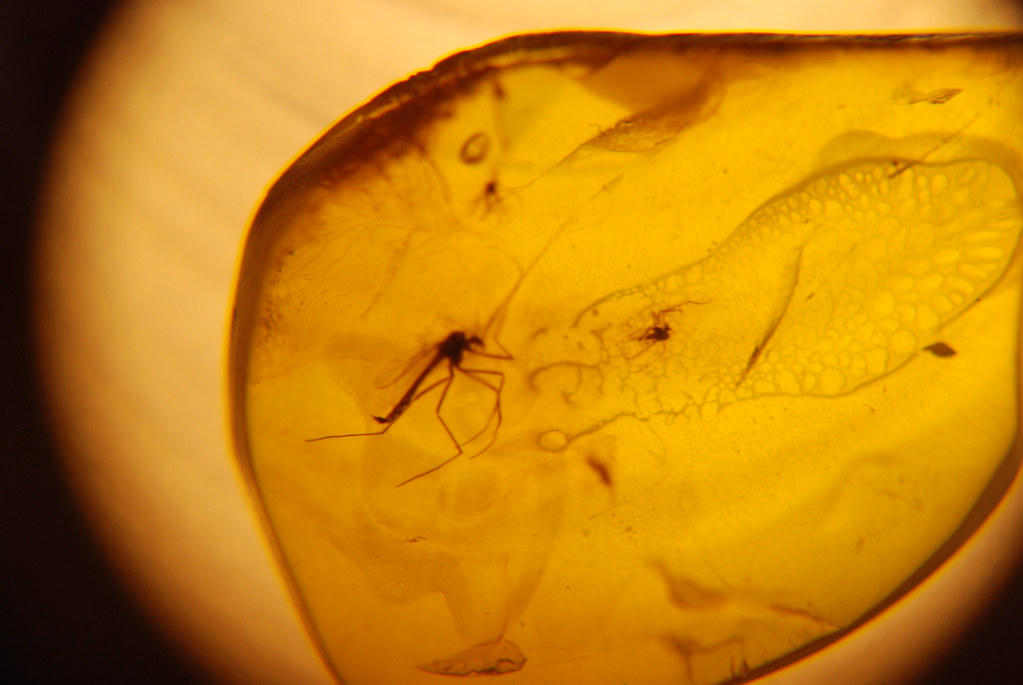

Amber Preserves the Impossible

Among the most incredible finds at Tanis are pieces of amber containing actual fragments of the asteroid impact itself. These golden time capsules hold microscopic debris from the day the dinosaurs died, including tiny crystals that could only have formed in the extreme heat of the impact.

The amber also preserves insects and other small organisms that were living their normal lives when catastrophe struck. Some contain beetles and flies that may have been attracted to the chaos, while others hold plant fragments that show how vegetation responded to the sudden environmental changes.

What makes these amber discoveries truly remarkable is their immediate connection to the impact event. Unlike most amber that forms over long periods, these pieces appear to have been created rapidly as tree resins were heated and hardened by the impact’s effects, trapping whatever happened to be nearby at that exact moment.

Dinosaur Bone Fragments: Direct Victims

While complete dinosaur skeletons are rare at Tanis, bone fragments found throughout the site provide direct evidence that dinosaurs were among the immediate victims of the impact. These aren’t fossils from creatures that died gradually over thousands of years—they’re from animals that perished within hours or days of the asteroid strike.

The bone fragments show signs of rapid burial and exceptional preservation, suggesting they came from animals that died suddenly and were quickly covered by impact-related sediments. Some fragments even show what appear to be bite marks from scavengers, indicating that some animals survived long enough to begin feeding on the dead before succumbing themselves.

Perhaps most intriguingly, some of these dinosaur remains have been found in direct association with the glass spherules, suggesting these massive reptiles were present when the deadly rain began falling from the sky. It’s the closest we may ever come to witnessing a dinosaur’s final moments.

The Forest That Burned in Minutes

The plant fossils at Tanis tell their own story of instantaneous destruction and remarkable preservation. Leaves, branches, and even entire tree trunks show evidence of flash heating and rapid burial, creating a snapshot of how forests responded to the impact’s immediate effects.

Many plant specimens show signs of charring and burning, consistent with the intense heat pulse that followed the impact. This heat was so severe it could ignite vegetation across entire continents, creating global wildfires that added smoke and ash to an already darkened sky.

The rapid burial of these plant materials created conditions perfect for preservation, maintaining cellular detail that’s normally lost in the fossilization process. Scientists can still identify individual plant species and even study their cellular structure, providing unprecedented insight into the ecosystem that existed at the moment of impact.

Marine Life Caught in Chaos

The Tanis site preserves an incredible diversity of marine creatures that were literally caught between life and death as the impact’s effects reached them. Ancient sharks, rays, and marine reptiles are found jumbled together with freshwater species in deposits that speak to the complete disruption of normal aquatic ecosystems.

Many of these marine fossils show signs of having been violently tossed about by seismic waves and impact-generated tsunamis. Some sharks are found far from where they would normally live, apparently carried inland by massive waves and left stranded as waters receded.

The preservation of soft tissues in some of these marine specimens is extraordinary, with scales, skin, and even stomach contents still intact. This level of preservation only occurs under very specific conditions—the kind that existed during the chaotic hours following the asteroid impact.

The Mammal That Almost Made It

Among the most poignant discoveries at Tanis is a small mammal fossil that appears to have survived the initial impact only to perish in the aftermath. This tiny creature, about the size of a modern rat, was found in a burrow that it had apparently retreated to as conditions on the surface became unbearable.

The mammal’s position suggests it was trying to escape the chaos above ground, perhaps fleeing from the falling debris, intense heat, or toxic atmosphere that followed the impact. Its burrow shows signs of rapid filling with impact-related sediments, suggesting the animal’s refuge ultimately became its tomb.

This fossil is particularly significant because it represents the kinds of small mammals that would go on to inherit the Earth after the dinosaurs’ extinction. The fact that this individual didn’t make it serves as a sobering reminder of just how close life came to total extinction during this catastrophic event.

Microscopic Evidence of Global Catastrophe

The sediments at Tanis contain microscopic evidence that connects this local catastrophe to the global disaster that ended the age of dinosaurs. Pollen and spores found in the death assemblage show dramatic changes in plant communities that occurred within days or weeks of the impact.

Chemical analysis of the sediments reveals elevated levels of iridium—a rare element that’s more common in asteroids than in Earth’s crust. This iridium spike, found worldwide in rocks of the same age, provides the chemical fingerprint that definitively links local extinctions to the global catastrophe.

Perhaps most remarkably, the microscopic fossils preserve evidence of the impact winter that followed the initial destruction. Changes in marine plankton and other microscopic life forms show how quickly global ecosystems collapsed as dust and debris blocked sunlight and disrupted the food chain.

Fossilization in Fast-Forward

The exceptional preservation at Tanis required a perfect storm of geological conditions that occurred within hours of the impact. The rapid burial of organisms in fine sediments, combined with the unique chemistry of impact-related debris, created conditions that allowed soft tissues and delicate structures to fossilize.

Normal fossilization is a slow process that typically destroys most organic material, leaving only bones and shells behind. But the catastrophic conditions at Tanis essentially “flash-fossilized” entire organisms, preserving details that are almost never seen in the fossil record.

The chemistry of the impact debris also played a crucial role in preservation. The glass spherules and shocked minerals created an alkaline environment that helped prevent decay, while rapid sedimentation sealed organisms away from oxygen and bacterial decomposition. It was nature’s own version of instant preservation.

What the Fossils Tell Us About Impact Physics

The Tanis fossils provide unprecedented insight into the physics of asteroid impacts and their immediate effects on life. The precise timing and sequence of events preserved in the rock layers help scientists understand how destruction spread outward from the impact site at the speed of sound and beyond.

The distribution of glass spherules and shocked minerals shows how impact debris was ejected into space and then rained back down across North America within hours of the initial collision. This ballistic debris created a brief but intense period of heating that may have been hot enough to ignite vegetation across entire continents.

The fossil evidence also helps scientists understand how seismic waves traveled through the Earth’s crust, triggering secondary disasters thousands of miles from the impact site. The Tanis deposits show that these earthquake-generated waves were powerful enough to create massive underwater disturbances that killed marine life across vast areas.

The Final Moments of the Mesozoic Era

The discoveries at Tanis represent more than just individual fossils—they’re a window into the final moments of an entire geological era. For 180 million years, dinosaurs had ruled the Earth, but in a single day, their dominance came to a catastrophic end that these fossils document with heartbreaking clarity.

The death assemblage at Tanis captures the transition from the Mesozoic Era to the Cenozoic Era—from the age of dinosaurs to the age of mammals. It’s a moment of profound biological change preserved in stone, showing how quickly life on Earth can be transformed by cosmic events beyond our control.

As we study these fossils, we’re not just learning about prehistoric life—we’re gaining insight into the fragility and resilience of life itself. The creatures that died at Tanis remind us that Earth’s history is punctuated by catastrophic events that can reshape the entire trajectory of evolution in a matter of hours.

The fossils at Tanis stand as a testament to one of Earth’s most dramatic days—a day when an ordinary moment became the final chapter for countless species. These remarkable specimens don’t just tell us about death; they reveal the incredible story of how life persists, adapts, and ultimately finds new ways to flourish even after unimaginable catastrophe. When you look at these fossils, you’re literally seeing the moment when one world ended and another began. What other secrets might be hiding in the rocks beneath our feet, waiting to tell their own stories of survival and extinction?