When we envision the Ice Age, few creatures capture our imagination quite like the saber-toothed tiger. With its impressive canines and powerful build, this prehistoric feline has become an icon of Pleistocene megafauna. But was it truly the apex predator of its time? Despite its popular portrayal as the most fearsome hunter of the Ice Age, the reality of this extinct cat is more nuanced. From its hunting strategies to its competition with other predators, the saber-toothed tiger—or more accurately, Smilodon—presents a fascinating case study in prehistoric predator ecology. This article explores what made these magnificent creatures both similar to and distinct from modern big cats, and evaluates their status among the pantheon of Ice Age hunters.

Not Actually a Tiger: Taxonomy and Naming

Despite its common name, the saber-toothed “tiger” wasn’t related to modern tigers at all. Scientists classify it in the genus Smilodon, a distinct lineage separate from today’s big cats (Panthera). This prehistoric predator belonged to the Machairodontinae subfamily, an extinct group of felines characterized by their elongated canine teeth. Three Smilodon species have been identified: S. gracilis (the smallest and earliest), S. fatalis (the most widespread throughout North America), and S. populator (the largest species, found in South America). The misnomer “tiger” stems from early paleontologists who noted superficial similarities with modern tigers, but genetic studies confirm they diverged from the lineage leading to modern cats approximately 20 million years ago. Understanding this taxonomic distinction helps us appreciate that saber-toothed cats represented a completely different evolutionary experiment in feline predation strategies.

The Iconic Canines: Form and Function

The most distinctive feature of Smilodon was undoubtedly its remarkably long canine teeth, which could reach up to 11 inches in the largest species. Unlike the conical teeth of modern big cats, these canines were flattened, curved, and serrated along the edges—resembling deadly blades rather than puncturing tools. This specialization wasn’t merely for show; it represented a highly evolved killing adaptation. The teeth were surprisingly fragile for their size, which contradicts the misconception that they were used to stab prey indiscriminately. Instead, paleontologists believe Smilodon used these teeth for precision slashing of soft tissues, particularly the throat, after immobilizing prey with its powerful forelimbs. CT scans of Smilodon skulls reveal reinforced roots and specialized muscle attachments that helped protect these valuable weapons from breakage during use. The saber teeth represented an evolutionary tradeoff: they were devastatingly effective killing tools but required specific hunting techniques to avoid damage.

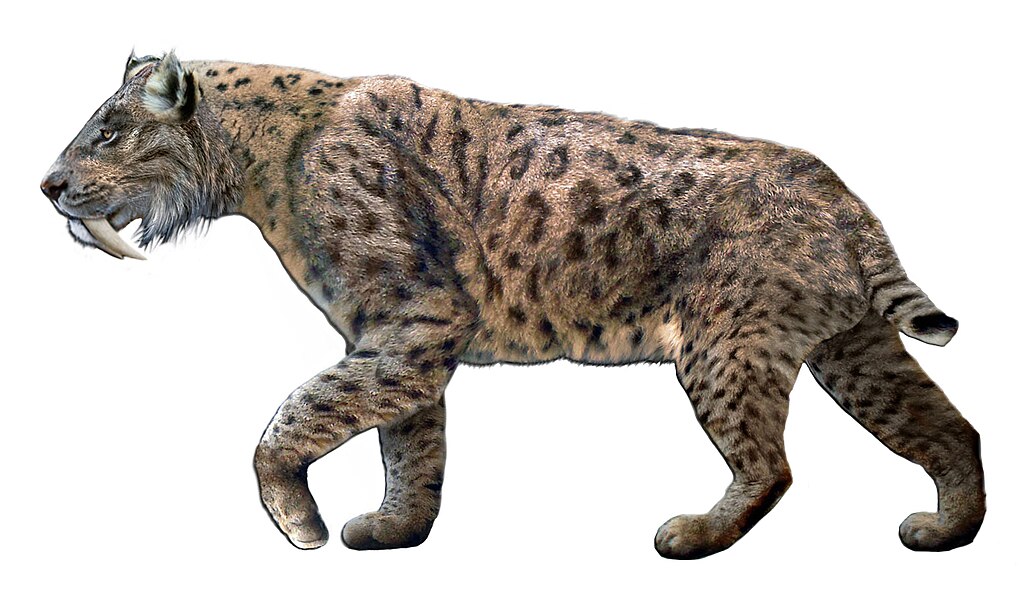

Built for Power: Physical Characteristics

Smilodon’s physical build differed significantly from modern big cats, emphasizing power over speed. Standing about 3 feet tall at the shoulder and weighing between 160-620 pounds (depending on species), Smilodon was stockier and more muscular than comparable modern felines. Its forelimbs were exceptionally powerful, with enlarged attachment points for muscles that would have allowed it to grapple and subdue struggling prey. This front-heavy design is further evidenced by its relatively shorter hindlimbs and a shorter, more bobcat-like tail that would have limited its running speed and agility. The neck muscles were particularly robust, designed both to support its large head and to provide the power needed for the specialized killing bite. Skeletal analysis shows that Smilodon’s spine was less flexible than that of modern cats, further supporting the theory that it was an ambush predator rather than a pursuit hunter. This combination of features created a predator perfectly designed for close-quarters combat with large, powerful prey.

Hunting Strategies: The Ambush Specialist

Unlike modern lions or wolves that can chase prey over long distances, Smilodon was built for ambush hunting and short, powerful confrontations. Its skeletal structure suggests limited endurance and speed compared to modern cats, making long pursuits impractical. Paleontologists theorize that Smilodon would stalk prey from dense vegetation or natural cover before launching a sudden, explosive attack. Once it closed the distance, Smilodon would use its powerful forelimbs to grapple and immobilize its target—possibly even wrestling larger prey to the ground. This immobilization was crucial since the elongated canines were vulnerable to breakage if the prey struggled too much during the killing bite. The final kill would likely involve a precise slash to the throat or belly, severing major blood vessels and ensuring a relatively quick death. This hunting strategy was particularly effective against the megafauna of the Pleistocene, including giant ground sloths, bison, young mammoths, and other large herbivores that dominated the landscape.

Preferred Prey: Targeting the Megafauna

Smilodon evolved during a time when North and South America teemed with massive herbivores, providing abundant prey options for a powerful predator. Analysis of isotopes from Smilodon fossils, particularly from the famous La Brea Tar Pits, indicates that they primarily hunted large herbivores like bison, camels, horses, and juvenile mammoths or mastodons. Their specialized anatomy made them particularly effective at taking down prey substantially larger than themselves—a niche that would have minimized direct competition with other carnivores. Unlike many modern predators that target the young, old, or weak members of prey species, Smilodon’s powerful build may have allowed it to successfully attack prime-aged adults. Paleontologists have discovered Smilodon teeth marks on the bones of various megafauna species, providing direct evidence of their hunting preferences. This specialization in large prey may have contributed to their eventual extinction, as many of these megafauna species disappeared at the end of the Pleistocene, eliminating Smilodon’s food source.

Social Structure: Lone Hunter or Pack Predator?

The social behavior of Smilodon remains one of the most debated aspects of its biology. Unlike modern big cats that leave clear evidence of their social structures in contemporary observations, we must rely on fossil evidence to reconstruct Smilodon’s lifestyle. Several lines of evidence suggest that at least some Smilodon species may have been more social than previously thought. Fossil deposits at the La Brea Tar Pits have yielded numerous Smilodon specimens of varying ages and both sexes, suggesting they might have hunted in groups. Additionally, paleontologists have discovered Smilodon fossils with healed injuries that would have temporarily prevented successful hunting, indicating these individuals may have been fed by others in a social group. The specialized hunting technique required to utilize the saber teeth effectively might have benefited from cooperative hunting, particularly when targeting the largest prey. However, not all researchers agree with this interpretation, and the debate continues about whether Smilodon was predominantly solitary like tigers or social like lions.

Geographic Range: A Widespread Success

Smilodon species collectively occupied a vast geographic range spanning much of the Western Hemisphere during the Pleistocene epoch. Smilodon gracilis, the earliest and smallest species, appeared approximately 2.5 million years ago in North America. Smilodon fatalis evolved from S. gracilis and became widespread throughout North America, eventually expanding into northwestern South America after the formation of the Isthmus of Panama. The largest species, Smilodon populator, evolved in South America and spread throughout that continent, with fossils discovered from Venezuela to Patagonia. This extensive distribution across diverse habitats—from grasslands and open woodlands to more densely forested regions—demonstrates Smilodon’s remarkable adaptability as a predator. Fossil evidence indicates that Smilodon could thrive in varied climates and environments, though they appear to have been most successful in areas with sufficient cover for ambush hunting and abundant large prey. This geographic versatility contributed to Smilodon becoming one of the most successful and widespread large predators of the Pleistocene epoch.

The Competition: Other Ice Age Predators

Smilodon didn’t rule the Pleistocene unchallenged—it shared its territory with several other formidable carnivores that would have competed for resources. In North America, the American lion (Panthera atrox), significantly larger than modern African lions, represented a different hunting strategy with its traditional big cat anatomy. The dire wolf (Canis dirus), hunting in coordinated packs, would have competed for similar prey. The short-faced bear (Arctodus simus), standing over 11 feet tall when rearing up, was potentially both a predator and scavenger that might have driven Smilodon from its kills. In South America, Smilodon populator faced competition from the jaguar-sized saber-toothed Homotherium and the bear-sized Arctotherium. This diversity of predators suggests a complex ecosystem with different hunting specializations reducing direct competition. Evidence from the La Brea Tar Pits indicates that these various predators targeted different prey or hunted in separate habitats, allowing multiple apex predators to coexist. This ecological partitioning challenges the notion of any single species being the “ultimate” predator of the Ice Age.

Vulnerabilities and Limitations

Despite its fearsome reputation, Smilodon had significant vulnerabilities that countered its predatory advantages. Its specialized dentition, while devastatingly effective for killing, was also prone to breakage—a potentially fatal injury for a predator. Fossil evidence shows that many Smilodon specimens suffered from broken teeth, arthritis, and injuries likely sustained during hunting. The predator’s limited speed meant it couldn’t effectively pursue prey across open terrain, restricting its hunting to environments with adequate cover. Smilodon’s specialized hunting strategy also required substantial learning and practice, making juvenile survival challenging. Their reliance on large prey animals made them vulnerable to ecosystem changes—as the Pleistocene megafauna began to disappear, Smilodon would have struggled to adapt to smaller prey that could outrun them or didn’t require their specialized killing technique. These limitations reveal Smilodon not as an invincible super-predator, but as a highly specialized hunter whose adaptations were perfectly suited to a specific ecological niche that ultimately disappeared.

Extinction: The End of the Saber-Tooths

Smilodon disappeared approximately 10,000 years ago, coinciding with the end of the last Ice Age and the beginning of the Holocene epoch. This extinction aligned with two major ecological events: dramatic climate change that transformed landscapes across the Americas and the arrival of human hunters in the New World. The warming climate altered vegetation patterns, affecting the distribution and abundance of the large herbivores Smilodon depended upon. Simultaneously, early human hunters may have competed with Smilodon for prey or directly hunted the same large mammals to extinction. Unlike more adaptable predators such as wolves and pumas that survived this transition, Smilodon’s extreme specialization for hunting large prey likely prevented it from adapting to a world with fewer megafauna. Intriguingly, no evidence has been found of humans directly hunting Smilodon, suggesting their extinction resulted from ecosystem collapse rather than direct persecution. The disappearance of these magnificent predators represents one of the most significant losses in the wave of extinctions that marked the end of the Pleistocene megafauna.

Scientific Discoveries: La Brea Tar Pits and Beyond

Our most detailed understanding of Smilodon comes from the remarkable fossil record preserved at the La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles, California. Over 2,000 Smilodon fatalis individuals have been recovered from these asphalt seeps, providing an unprecedented sample size for studying this extinct predator. The tar pits formed when natural asphalt seeped to the surface, creating sticky pools that entrapped animals that ventured into them. Predators like Smilodon were often lured to these sites by struggling herbivores, becoming trapped in a deadly cycle. This preservation method has yielded complete skeletons in exceptional condition, allowing detailed analyses of Smilodon’s anatomy, growth patterns, pathologies, and population structure. Beyond La Brea, significant Smilodon discoveries have been made throughout the Americas, including the Talara Tar Seeps in Peru and numerous cave sites in Brazil that have yielded Smilodon populator fossils. New analytical techniques, including ancient DNA studies, isotope analysis, and advanced imaging, continue to reveal new insights about these iconic Ice Age predators, though complete ancient DNA recovery remains elusive.

Cultural Impact: Smilodon in the Popular Imagination

Few prehistoric animals have captured the public imagination quite like the saber-toothed tiger. Since its first scientific description in the 19th century, Smilodon has become an icon of prehistoric life, appearing in countless documentaries, films, books, and television programs. Perhaps most famously, the character of Diego in the “Ice Age” animated film franchise brought a talking (if somewhat anatomically inaccurate) Smilodon to global audiences. Natural history museums worldwide feature Smilodon displays as centerpiece exhibits, with the dramatic snarling mount from the La Brea Tar Pits Museum being particularly influential in shaping public perception. The predator’s striking appearance has made it a popular subject for paleoart, with reconstructions evolving as scientific understanding has improved. Smilodon has also been adopted as a mascot by numerous sports teams and organizations, including the NHL’s Nashville Predators, whose logo features stylized saber-tooth elements. This cultural prominence has helped maintain public interest in paleontology and Ice Age ecosystems, making Smilodon an ambassador for scientific education about extinct species.

The Ultimate Ice Age Predator? A Balanced Assessment

Was Smilodon truly the ultimate Ice Age predator? The evidence suggests a more nuanced reality than this superlative title implies. Smilodon was undoubtedly a formidable hunter with specialized adaptations that made it extraordinarily effective at killing large prey in specific circumstances. Its powerful build, devastating canines, and ambush-hunting strategy created a predatory package unmatched by any modern cat. However, Smilodon coexisted with numerous other apex predators that had their own specialized hunting adaptations. The American lion could likely outrun Smilodon and take down similar prey. Dire wolf packs could pursue prey over longer distances. Short-faced bears combined size and power that even Smilodon would have respected. Rather than crowning any single species as the “ultimate” predator, it’s more accurate to view the Pleistocene as supporting a diverse guild of top carnivores, each exploiting different hunting strategies and ecological niches. Smilodon’s extinction—alongside many of these competitors—suggests that specialized hunting prowess wasn’t enough to survive the dramatic environmental changes at the Pleistocene-Holocene boundary.

The saber-toothed tiger stands as a magnificent example of evolutionary specialization—a predator perfectly adapted to the unique conditions of the Pleistocene epoch. Its distinctive canines, powerful build, and specialized hunting techniques made it one of the most effective and iconic predators in Earth’s history. Yet its ultimate extinction reminds us that even the most perfectly adapted species can become vulnerable when environments change dramatically. Rather than the singular “ultimate” Ice Age predator, Smilodon represents one spectacular solution to the evolutionary challenge of large carnivore ecology—a solution that worked brilliantly for hundreds of thousands of years before changing conditions rendered it obsolete. By studying these remarkable extinct predators, we gain valuable insights into evolutionary processes, ecological relationships, and the dynamic nature of life on our planet throughout its history.