For millions of years, dinosaurs dominated Earth’s landscapes, evolving into an incredibly diverse array of species that ranged from the massive Argentinosaurus to the chicken-sized Compsognathus. While paleontologists have made remarkable strides in understanding dinosaur anatomy, behavior, and evolution, questions about their life cycles—particularly how they aged—remain fascinating areas of ongoing research. Unlike studying modern animals, scientists must piece together clues from fossilized remains to understand how dinosaurs grew up, matured, and eventually grew old. This article explores what we know about aging in dinosaurs and how paleontologists determine the age of specimens that lived over 66 million years ago.

The Challenge of Determining Dinosaur Ages

Determining how old a dinosaur was when it died presents unique challenges to paleontologists. Unlike modern vertebrates that can be directly observed throughout their lifespans, dinosaurs left behind only their fossilized remains. Scientists must employ various techniques to estimate a specimen’s age, including bone histology (the microscopic study of bone structure), growth ring analysis, and comparative studies with living relatives. These methods have revealed that dinosaur growth patterns differed significantly from mammals, with many species experiencing rapid growth in their early years before eventually slowing down as they reached maturity. The absence of complete life histories for most dinosaur species makes it difficult to establish definitive maximum lifespans, but the evidence suggests many dinosaurs did indeed reach old age.

Growth Rings: Nature’s Timekeepers

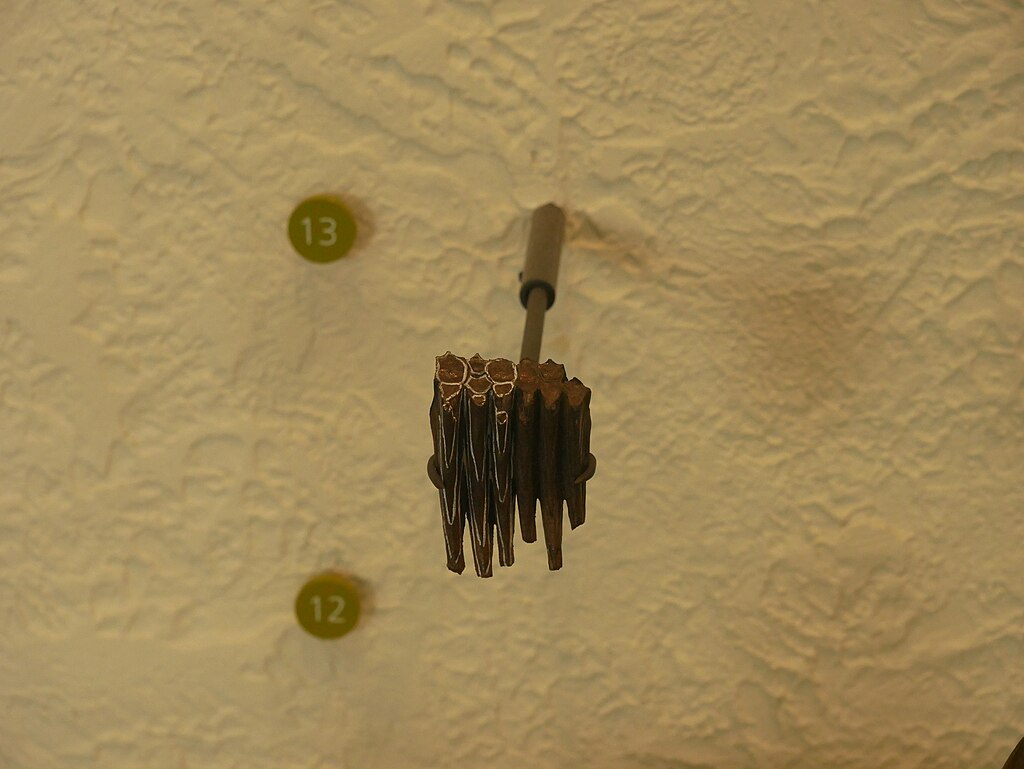

Perhaps the most valuable tool for determining dinosaur ages comes from studying growth rings in fossilized bones. Similar to tree rings, many dinosaurs developed annual growth marks in their bones called lines of arrested growth (LAGs). These rings formed during seasons of environmental stress or resource scarcity, creating visible lines in the bone structure that can be counted to estimate age. By examining these growth rings under microscopes, paleontologists can determine not only how old a dinosaur was when it died but also track changes in its growth rate throughout its life. Studies of tyrannosaur specimens, for instance, have revealed that these fearsome predators experienced explosive growth during adolescence—gaining up to 4.6 pounds (2.1 kg) daily—before their growth slowed dramatically upon reaching sexual maturity around 20 years of age.

Bone Histology: Reading Microscopic Clues

Bone histology—the microscopic examination of bone tissue—provides invaluable insights into dinosaur aging processes. By creating thin sections of fossilized bone and studying them under microscopes, scientists can observe changes in bone structure that indicate different life stages. Young, rapidly growing dinosaurs typically had bones with numerous blood vessels and less dense tissue, while older individuals show more compact bone with fewer blood vessels. This pattern of remodeling and densification occurs as dinosaurs aged, much like in modern animals. Studies of bone histology have also revealed that different dinosaur species matured at different rates, with some reaching adulthood within a few years while others took more than a decade. These variations likely reflected different evolutionary strategies and ecological niches, similar to the diversity of life histories observed in modern animals.

The Longest-Lived Dinosaurs

Evidence suggests that some dinosaur species could reach considerable ages, particularly the larger sauropods. Based on growth ring analysis and bone histology, scientists estimate that some sauropods like Diplodocus and Apatosaurus may have lived between 70-80 years or possibly longer. These massive herbivores likely benefited from their sheer size, which offered protection against predators and allowed them to reach advanced ages in the wild. In contrast, smaller dinosaur species generally had shorter lifespans, with many medium-sized theropods potentially living 20-30 years. Tyrannosaurus rex, despite its fearsome reputation, likely had a maximum lifespan of about 28-30 years based on the oldest specimens found to date. Interestingly, evidence suggests most T. rex specimens never reached this maximum age, suggesting many died from predation, disease, or environmental challenges before reaching their biological limits.

Senescence in Dinosaurs: Did They Experience Old Age?

Senescence—the biological process of deterioration that comes with aging—appears to have affected dinosaurs much as it does modern animals. Paleontologists have identified several indicators of senescence in dinosaur fossils, including arthritis, bone infections, and dental wear. One famous example is “Sue,” the most complete T. rex skeleton ever found, which shows evidence of arthritis, broken and healed ribs, and a jaw infection that would have made eating difficult. These pathologies suggest Sue lived long enough to experience age-related deterioration, estimated to be around 28 years old at death. Other specimens across various dinosaur species show similar signs of advanced age, including fused vertebrae, extensive bone remodeling, and evidence of healed injuries accumulated over long lifespans. These findings confirm that dinosaurs did indeed experience physical aging, though the specific manifestations varied across species.

Growth Strategies: Fast-Growing vs. Slow-Growing Dinosaurs

Dinosaurs exhibited remarkably diverse growth strategies that influenced how quickly they matured and how long they lived. Some species, particularly smaller theropods and ornithischians, grew rapidly and reached sexual maturity within a few years, similar to many modern birds. This fast-growth strategy likely evolved as a response to high predation pressure, allowing these dinosaurs to reproduce quickly before falling victim to larger carnivores. In contrast, the massive sauropods followed a different pattern, growing continuously throughout much of their lives, though their growth rate slowed substantially after reaching sexual maturity. This extended growth period enabled sauropods to reach their enormous sizes while potentially contributing to their longer lifespans. These different growth strategies represent evolutionary adaptations to different ecological niches and pressures, highlighting the diversity of life history strategies among dinosaurs.

Sexual Maturity vs. Physical Maturity

An important distinction in understanding dinosaur aging is the difference between sexual maturity and skeletal maturity. Research suggests that many dinosaur species became capable of reproduction before their skeletons were fully developed—a pattern also seen in some modern reptiles and birds. Evidence for this comes from specimens showing medullary bone (a calcium-rich tissue formed in female birds during egg-laying) in individuals whose growth rings indicate they were not yet fully grown. This reproductive strategy provided evolutionary advantages, allowing dinosaurs to contribute to the next generation even while still growing themselves. The timing of sexual maturity varied widely across dinosaur groups, with some smaller species likely reaching reproductive age within 2-3 years, while larger species might not reproduce until 8-10 years of age or later. This disconnection between sexual and physical maturity complicates our understanding of what constituted “adulthood” for different dinosaur species.

Evidence of Elderly Dinosaurs in the Fossil Record

The fossil record has provided compelling examples of dinosaurs that reached advanced ages before death. One remarkable specimen is a Triceratops nicknamed “Kelsey,” which shows evidence of being exceptionally old at death, with highly fused sutures in its skull, extensive bone remodeling, and signs of arthritis in several joints. Similarly, some hadrosaur specimens show extensive dental batteries with extreme wear, indicating these individuals lived long enough to significantly wear down their teeth through decades of grinding plant material. Among theropods, older individuals can be identified by the accumulation of pathologies and injuries sustained throughout life, as well as by changes in bone structure visible through histological analysis. These elderly specimens provide precious insights into how dinosaurs aged, though they represent only a small fraction of recovered fossils, as many dinosaurs likely died before reaching advanced age due to predation, disease, or environmental challenges.

Aging Across Different Dinosaur Groups

Different dinosaur lineages exhibited varied aging patterns that reflected their evolutionary relationships and ecological roles. Theropods, the group that includes T. rex and raptors, generally followed a growth pattern surprisingly similar to birds (their modern descendants), with rapid early growth followed by a plateau upon reaching maturity. Many reached sexual maturity between 5-15 years depending on size, with larger species taking longer to mature. Sauropods, the long-necked giants, showed an extremely accelerated early growth phase that allowed them to quickly grow beyond the size range of most predators, followed by decades of slower growth. Ornithischians like Triceratops and hadrosaurs typically exhibited intermediate growth patterns, with moderate growth rates that slowed as they reached adult size. These different aging patterns evolved in response to various ecological pressures, including predation risk, resource availability, and reproductive strategies specific to each dinosaur group.

Comparing Dinosaur Aging to Modern Reptiles and Birds

Comparing dinosaur aging processes to their modern relatives provides valuable context for understanding these ancient creatures. Birds, as the direct descendants of theropod dinosaurs, share several aging characteristics with their extinct ancestors, including rapid early growth and determinate growth patterns where individuals reach a maximum size. However, most dinosaurs grew for longer periods than modern birds, which typically reach adult size within a year. Modern reptiles like crocodilians offer another useful comparison, as they exhibit indeterminate growth, continuing to grow slowly throughout their lives much like some dinosaur groups. The presence of growth rings in many reptiles has helped validate similar structures found in dinosaur bones. Despite these similarities, dinosaurs appear to have had unique growth strategies that don’t perfectly match either modern birds or reptiles, suggesting they occupied their own distinctive life history niche that has no exact modern equivalent.

Predation and Survivorship: Who Lived to Old Age?

The likelihood of a dinosaur reaching old age varied dramatically based on its species, size, and ecological role. Large adult sauropods, protected by their immense size, likely had high survivorship rates once they reached adulthood, with few predators capable of taking down a healthy adult Diplodocus or Brachiosaurus. This size advantage may explain why paleontologists find evidence of elderly sauropods in the fossil record. In contrast, smaller dinosaur species faced constant predation pressure throughout their lives, making it statistically less likely for individuals to reach maximum age. Fossil evidence suggests a significant percentage of medium-sized dinosaurs died before reaching full skeletal maturity. Interestingly, apex predators like adult Tyrannosaurus faced few threats from other predators but experienced high mortality rates from injuries, infections, and intraspecific combat—as evidenced by the numerous wounds found on fossilized specimens. These patterns highlight how ecology shaped the age demographics of different dinosaur communities.

Aging-Related Pathologies in Dinosaur Fossils

Fossilized dinosaur remains frequently display pathologies that provide windows into aging processes in these ancient animals. Arthritis appears to have been common in older dinosaurs, with joint deterioration visible in limb bones and vertebrae across multiple species. Some specimens show evidence of ossified tendons, bone spurs, and fusion between vertebrae—conditions typically associated with advanced age in modern animals. Dental pathologies also provide aging clues, with older herbivorous dinosaurs showing extensive tooth wear from decades of grinding fibrous plant material. Some specimens display evidence of cancer, infections that led to bone remodeling, and healed fractures that would have accumulated over long lifespans. One particularly interesting age-related pathology appears in some ceratopsian frills, where the distinctive ornamental structures show increased vascularization and bone remodeling in older individuals, suggesting these display features continued developing throughout life. These pathological markers help paleontologists identify the oldest individuals within dinosaur populations.

The End of the Line: Natural Death vs. Catastrophic Events

The ultimate fate of dinosaurs—both as individuals and as a group—raises fascinating questions about aging and mortality in the prehistoric world. For individual dinosaurs, natural death from old age was certainly possible, though likely less common than deaths from predation, disease, accidents, or environmental challenges. Fossil evidence suggests that some dinosaurs did live to advanced ages and may have died from age-related factors, as indicated by specimens showing multiple pathologies consistent with senescence. However, the mass extinction event at the end of the Cretaceous period dramatically altered this natural pattern, indiscriminately killing dinosaurs of all ages when an asteroid struck Earth 66 million years ago. This catastrophic event effectively prevented countless dinosaurs from experiencing their full potential lifespans, creating a unique endpoint in their evolutionary history. The only dinosaurs to survive this extinction were a lineage of small theropods that eventually evolved into modern birds, continuing the dinosaur aging story into the present day, albeit in dramatically transformed forms.

Through careful analysis of fossilized remains, scientists continue to unravel the mysteries of dinosaur growth and aging. The evidence clearly shows that dinosaurs, like modern animals, experienced the full spectrum of life stages from rapid juvenile growth to the physical deterioration of old age. While many questions remain about the exact lifespans of different species, paleontologists have established that some dinosaurs did indeed grow old, developing age-related pathologies similar to those seen in animals today. This research not only helps us understand these fascinating prehistoric creatures but also provides insights into the evolution of aging processes across vertebrate lineages. As technology advances and more specimens are discovered, our understanding of dinosaur life histories—including how they aged—will continue to grow, adding new chapters to one of Earth’s most captivating evolutionary stories.