In the shadows of prehistoric landscapes roamed a creature of such immense power and size that it could challenge the mighty mammoths themselves. The short-faced bear, scientifically known as Arctodus simus, stands as one of the most formidable predators to have ever walked North America. This colossal carnivore dominated the Pleistocene epoch, evolving into a perfect killing machine that would make today’s largest bears seem modest by comparison. As we journey back through time to examine this apex predator, we’ll discover how its exceptional adaptations, hunting prowess, and ecological role shaped the prehistoric world, and why this magnificent beast earns the title of history’s most powerful bear.

The Short-Faced Bear: An Overview

Arctodus simus, commonly known as the short-faced bear or bulldog bear, reigned across North America during the Pleistocene epoch, approximately 1.8 million to 11,700 years ago. As the largest known carnivorous land mammal that ever lived in North America, this bear species evolved as part of the Tremarctine subfamily, which includes today’s spectacled bears of South America. Its most distinctive feature—the shortened snout that gave the bear its common name—was just one of many adaptations that made this creature exceptionally efficient at dominating the Ice Age landscape. Fossil evidence suggests these bears stood up to 11 feet tall when rearing on their hind legs, far surpassing the size of any modern bear species. Their presence across the continent, from Alaska to Mexico, demonstrates their remarkable adaptability to various environments despite their specialized predatory lifestyle.

Record-Breaking Proportions

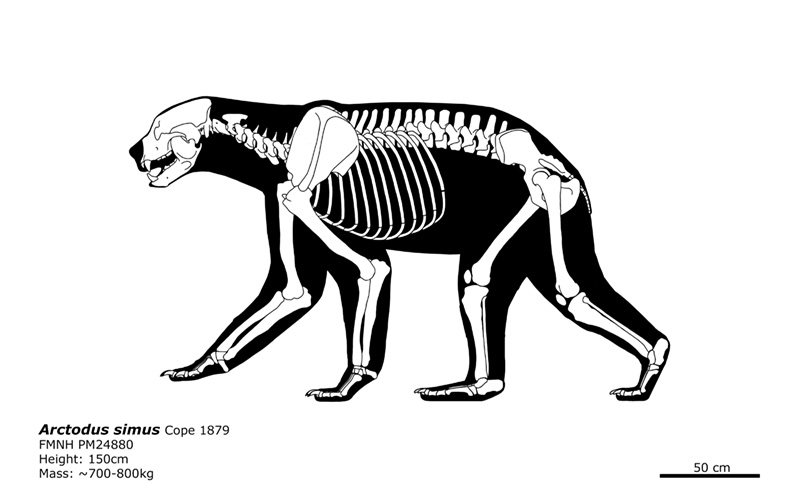

The short-faced bear’s sheer size alone made it one of the most intimidating creatures of its time, with estimates placing its weight between 1,500 to 2,000 pounds—nearly twice the size of the largest modern brown bears. Standing fully upright, these titans could reach heights of 11 feet, with some fossil specimens suggesting even larger individuals may have existed. Their shoulder height while on all fours measured approximately 5 to 6 feet, giving them a commanding presence on the prehistoric landscape. The bear’s limbs were proportionally longer than those of modern bears, with some paleontologists estimating they had limbs 30% longer relative to their body size than today’s bears. These extraordinary proportions weren’t just impressive—they were functional adaptations that allowed the short-faced bear to cover vast territories and pursue prey with remarkable efficiency across the Pleistocene plains.

Evolutionary History

Arctodus simus evolved from earlier bear species that crossed from Asia to North America approximately 2 million years ago, at the beginning of the Pleistocene epoch. This genus developed alongside changing environments and prey adaptations, gradually specializing into the formidable predator that would dominate the continent for nearly two million years. Fossil evidence shows that the short-faced bear likely evolved from the Ursavus lineage, which gave rise to most modern bear species. Unlike its omnivorous cousins, however, Arctodus evolved toward hypercarnivory—a specialized diet consisting almost exclusively of meat. This evolutionary pathway led to substantial changes in cranial structure, limb proportions, and overall size that distinguished the short-faced bear from its contemporaries. The species reached its peak during the middle and late Pleistocene, when it had adapted perfectly to the role of North America’s dominant land predator, filling a niche similar to that of big cats on other continents.

Unique Anatomy and Adaptations

The short-faced bear possessed a suite of anatomical adaptations that made it exceptionally well-suited for a predatory lifestyle. Its shortened snout—which inspired its common name—provided a more powerful bite force due to improved mechanical advantage in the jaw muscles. Unlike the dished face profile of grizzly bears, the short-faced bear had a more straight-lined profile that housed larger nasal passages, potentially giving it an enhanced sense of smell for detecting prey over vast distances. The bear’s legs were remarkably long for a member of the Ursidae family, suggesting an adaptation for sustained pursuit rather than the ambling gait of modern bears. These powerful limbs ended in massive paws armed with claws estimated to be up to six inches in length—lethal weapons for bringing down large prey. Perhaps most striking was the bear’s relatively slender build compared to modern bears, with a body designed more for speed and endurance than the bulky frames adapted for omnivorous foraging we see in contemporary bear species.

The Case for Hunting Mammoths

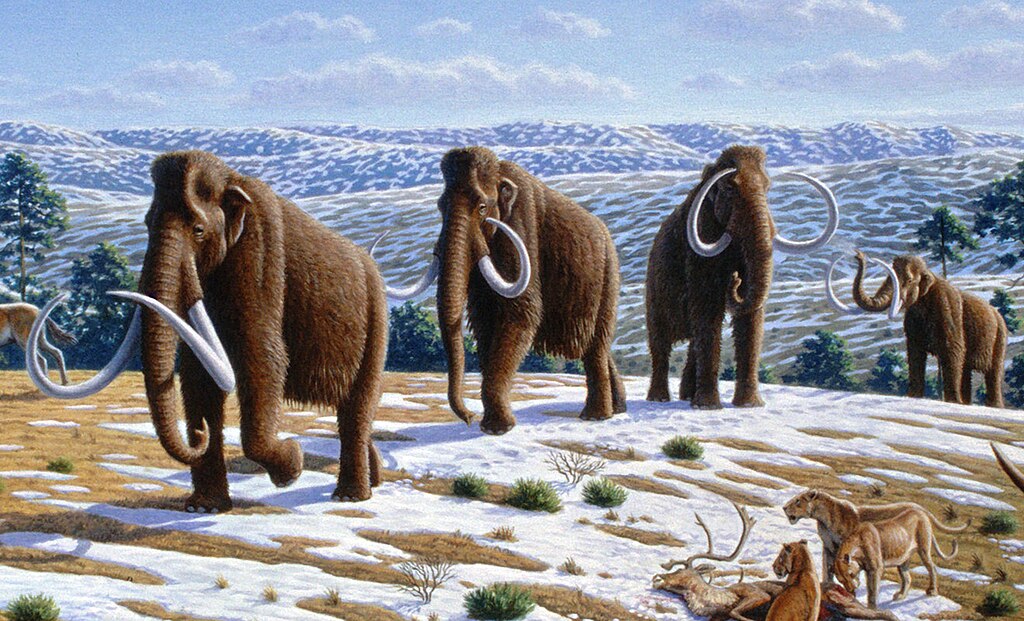

The controversial proposition that short-faced bears could have hunted mammoths is supported by several lines of evidence that paint a compelling picture of these bears as mega-predators. The sheer size and power of Arctodus simus would have given it the physical capability to confront even adult mammoths, particularly if hunting in loose social groups or targeting vulnerable individuals. Bite force calculations based on skull morphology suggest that the short-faced bear had one of the most powerful bites of any land mammal, capable of crushing mammoth bones to extract nutritious marrow. Modern bears have been documented taking down moose and bison—the largest modern equivalents—lending credence to the possibility that their larger prehistoric relatives could manage even bigger prey. Some fossil sites have revealed mammoth remains with damage patterns consistent with large carnivore predation, though definitively linking these to short-faced bears remains challenging. Perhaps most convincingly, stable isotope analysis of short-faced bear fossils indicates a diet heavily dependent on large herbivores, including species in the size range of mammoths and their calves.

Hunting Strategies and Prey Preferences

The short-faced bear likely employed a combination of hunting strategies that leveraged its unique anatomical adaptations to secure prey. Unlike ambush predators, this bear’s long limbs and cursorial adaptations suggest it was capable of sustained pursuit across open terrain, potentially reaching speeds of 35-40 mph in short bursts—faster than any modern bear. Paleobiologists theorize that Arctodus may have specialized in running down prey over moderate distances, using its superior endurance to exhaust fleeing animals before delivering powerful killing blows with its massive forelimbs and claws. Evidence from bone accumulations at fossil sites indicates the short-faced bear favored megafauna like bison, horses, ground sloths, and possibly young or weakened mammoths and mastodons. Some researchers suggest these bears may have practiced kleptoparasitism—stealing kills from other predators like dire wolves and American lions by using their enormous size to intimidate the original hunters. The bear’s impressive sense of smell, potentially enhanced by its specialized nasal passages, would have allowed it to detect carrion or vulnerable prey from extraordinary distances, making it an opportunistic hunter that could exploit various food sources across its extensive range.

Competing with Other Ice Age Predators

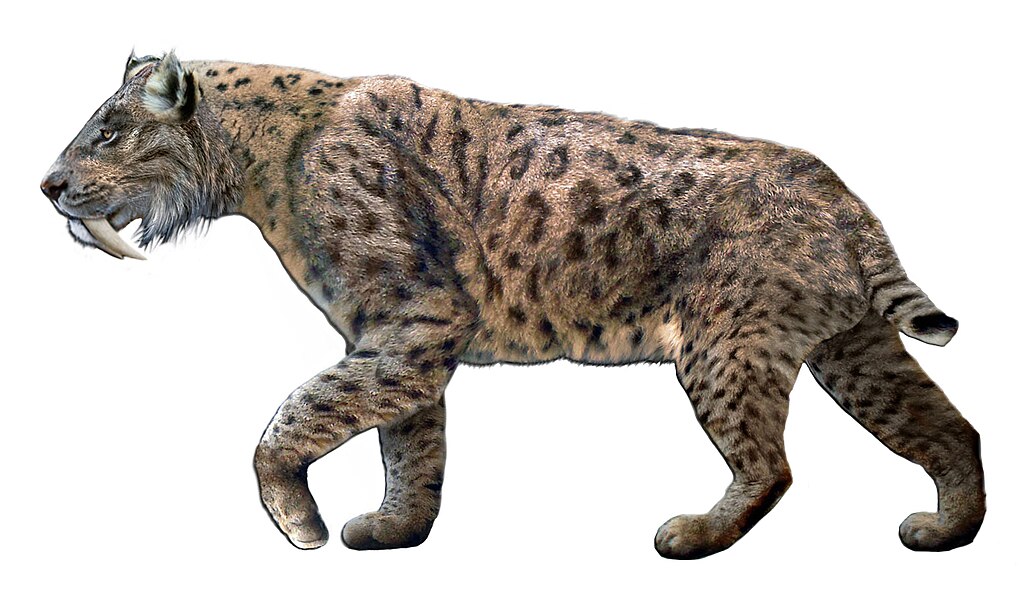

The Pleistocene landscapes of North America featured an impressive assembly of apex predators, creating a competitive environment where the short-faced bear had to establish its dominance. Among its contemporaries were the American lion (Panthera atrox), saber-toothed cats (Smilodon fatalis), dire wolves (Canis dirus), and the American cheetah (Miracinonyx trumani)—each specialized for different hunting niches. The short-faced bear likely maintained its position at the top of this predatory hierarchy through sheer size and aggression, able to drive competitors from kills and monopolize prime hunting territories. Fossil evidence sometimes shows concentrated remains of these various predators at common feeding sites, suggesting intense competition over carcasses of large megafauna. The bear’s versatility as both active hunter and opportunistic scavenger likely gave it an advantage during seasonal scarcity when specialized hunters might struggle. Some paleontologists hypothesize that the overlapping territories and competition between these formidable predators may have driven the evolution of ever-larger body sizes and more specialized hunting techniques in a prehistoric arms race that shaped the entire predator guild of Ice Age North America.

Habitat and Geographic Range

The short-faced bear dominated a vast territory across North America, with fossil evidence confirming its presence from Alaska and the Yukon through the continental United States and as far south as central Mexico. This expansive range encompassed diverse habitats, from tundra and boreal forests in the north to grasslands and more temperate environments in the south. Arctodus seems to have preferred open habitats where its speed and endurance could be leveraged for hunting, though it was clearly adaptable to various environments. The species thrived particularly well in the massive prairie ecosystems that dominated much of North America during the Pleistocene, where large herds of herbivores provided abundant prey. Fossil distributions suggest these bears may have followed seasonal migration patterns of their prey species, potentially covering enormous territories that dwarfed the already-impressive ranges of modern bears. Some evidence points to the short-faced bear having a higher population density in regions where megafauna congregated around water sources or prime grazing areas, creating predator hotspots during the Pleistocene that would have been truly intimidating landscapes for early human arrivals to the continent.

Calculating Its Bite Force and Strength

Paleobiologists have used sophisticated biomechanical modeling to estimate the bite force of Arctodus simus, yielding figures that underscore its status as one of history’s most powerful mammalian predators. Based on skull morphology, jaw muscle attachment sites, and tooth structure, researchers estimate the short-faced bear could generate bite forces exceeding 2,000 pounds per square inch at its carnassial teeth—roughly twice the bite force of a modern grizzly bear. This tremendous power would have enabled the bear to crush large bones, including mammoth femurs, to access nutritious marrow unavailable to less powerful predators. Beyond bite force, the bear’s overall strength has been calculated based on skeletal robusticity and muscle attachment sites, suggesting forelimb strength sufficient to deliver blows that could stun or kill animals as large as bison with a single strike. The combined power of its bite and limbs meant that once the short-faced bear closed distance with prey, few animals could withstand its attack. This exceptional strength, coupled with its speed and intelligence, created a predatory package that had no equal in the Pleistocene ecosystems of North America.

Dietary Analysis Through Fossil Evidence

Modern scientific techniques have provided remarkable insights into the diet of the short-faced bear, confirming its status as a hypercarnivore with a preference for large prey. Stable isotope analysis of carbon and nitrogen from preserved bone collagen reveals distinct signatures that place Arctodus firmly among specialized meat-eaters rather than omnivorous bears. These chemical signatures specifically indicate the consumption of large herbivores, with isotope ratios most consistent with predation on bison, horses, camels, and possibly juvenile mammoths. Microwear patterns on recovered teeth show scratches and pits characteristic of bone-crushing behavior, further supporting the bear’s role as a predator capable of processing large carcasses completely. Fossil assemblages occasionally feature bones of large mammals bearing distinctive puncture marks matching the tooth spacing of short-faced bears, providing direct evidence of predation. Coprolites (fossilized feces) attributed to Arctodus contain large amounts of processed bone fragments and hair from megafauna species, adding another line of evidence for its specialized carnivorous diet. This multi-faceted approach to dietary reconstruction paints a consistent picture of a top predator focusing on the largest available prey—including, potentially, mammoths.

Comparing to Modern Bears

The short-faced bear stands in stark contrast to its modern relatives, representing an evolutionary path that no contemporary bear species follows. While today’s largest bear—the Kodiak brown bear—can reach impressive sizes of up to 1,500 pounds, it falls short of Arctodus simus’s estimated 2,000-pound frame and lacks the specialized predatory adaptations. Modern bears are primarily omnivorous, with even the most carnivorous species like polar bears having anatomical features designed for a broader dietary range than the hypercarnivorous short-faced bear. The proportions differ dramatically as well; modern bears possess shorter, more robust limbs suited for powerful digging and climbing rather than the long, pursuit-adapted limbs of Arctodus. Cranial comparisons reveal that modern bears have longer snouts with dental adaptations for processing plant material, whereas the short-faced bear’s compressed skull housed massive jaw muscles and teeth specialized for meat-eating and bone-crushing. Perhaps most significantly, modern bears typically operate as solitary hunters of relatively small prey or scavengers, a far cry from the specialized megafauna hunter that Arctodus appears to have been. These differences highlight how the short-faced bear occupied a unique ecological niche that disappeared along with the Pleistocene megafauna it hunted.

Extinction Theories

The disappearance of the short-faced bear approximately 11,000 years ago coincides with the broader extinction event that claimed most of North America’s megafauna at the end of the Pleistocene. Multiple theories attempt to explain this apex predator’s extinction, with climate change featuring prominently among them. As the last ice age ended, ecosystem transformations dramatically reduced the open habitats where these bears excelled at hunting, while simultaneously diminishing populations of the megafauna they depended upon for food. The overkill hypothesis suggests that the arrival of sophisticated human hunters to North America may have created unsustainable competition for large prey animals, indirectly affecting the bear by eliminating its food sources. Some researchers propose a more direct conflict scenario, where early humans might have specifically targeted these enormous bears as dangerous competitors for the same hunting grounds and prey. Disease transmission from newly arrived species has also been suggested as a potential contributing factor. Most likely, the extinction resulted from a complex interaction of these factors—a perfect storm of environmental change, prey species collapse, and new competitive pressures that the specialized Arctodus could not adapt to quickly enough.

The Legacy of North America’s Super Predator

The evolutionary story of the short-faced bear offers profound insights into predator-prey dynamics and the development of carnivore adaptations. As North America’s dominant land predator for nearly two million years, Arctodus simus shaped the behavioral and physical evolution of its prey species, likely driving selection for increased speed, vigilance, and defensive adaptations in everything from bison to horses. The ecological niche it occupied—that of a specialized megafauna hunter—represented an evolutionary experiment in bear evolution that ultimately ended with the Pleistocene extinctions. Despite its disappearance, the short-faced bear’s legacy continues in scientific research, where studies of its remarkable adaptations inform our understanding of biomechanics, predator specialization, and the complex relationships within prehistoric ecosystems. The imposing presence of reconstructed Arctodus skeletons in natural history museums worldwide captivates visitors, offering a glimpse into a world where predators reached proportions seemingly impossible by today’s standards. Perhaps most importantly, understanding the rise and fall of this magnificent predator provides crucial context for conservation efforts focused on modern bears, reminding us how dramatically ecological conditions can shift and how even the most perfectly adapted species can disappear when environments change too rapidly.

Conclusion

The short-faced bear represents one of nature’s most impressive evolutionary experiments—a bear species that transcended the typical limitations of its family to become perhaps the most formidable land predator in North American history. With its massive frame, specialized anatomy, and remarkable hunting adaptations, Arctodus simus could indeed have challenged creatures as imposing as mammoths, particularly vulnerable individuals or calves. This super-predator’s reign through the Pleistocene demonstrates the extraordinary evolutionary potential within the bear lineage and highlights the dramatic ecological shifts that have occurred in North American ecosystems. Though extinct for roughly 11,000 years, the short-faced bear continues to inspire awe and scientific inquiry, offering a window into a lost world where megafauna roamed and mega-predators hunted across landscapes that still bear the ecological imprint of their presence. In understanding this magnificent prehistoric bear, we gain perspective on the dynamic forces that shape predator evolution and the delicate balance that sustains even the mightiest species on our planet.