Picture this: a massive Allosaurus from North America somehow encountering a fierce Yangchuanosaurus from China, or perhaps a European Cetiosaurus meeting its distant cousin from Argentina. These epic prehistoric encounters might fuel our imagination, but the harsh reality of Earth’s ancient geography tells a completely different story. During the Jurassic period, roughly 200 to 145 million years ago, our planet looked nothing like the connected world we know today, and the evidence is crystal clear about one thing – dinosaurs were trapped on their respective landmasses, unable to cross the vast oceans that separated them.

The Jurassic World Was Already Fractured

When most people think of the Jurassic period, they imagine a single, connected landmass where dinosaurs roamed freely across continents. The truth is far more complex and fascinating. By the time the Jurassic period began, the supercontinent Pangaea was already well into its breakup phase, having started splitting apart during the late Triassic period.

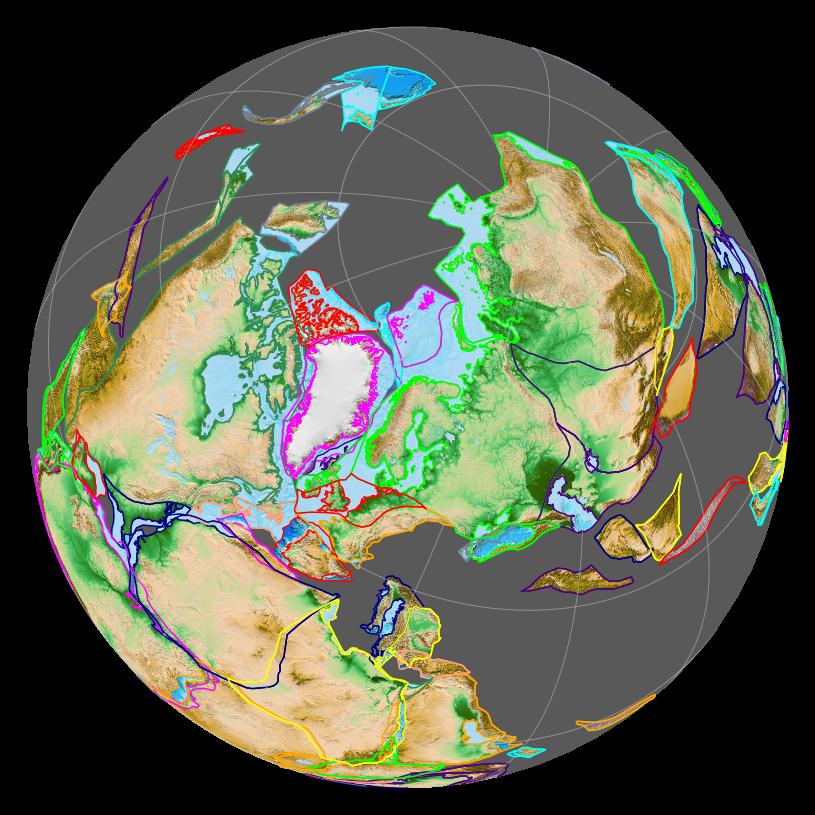

The massive landmass had fractured into several distinct pieces, with the Tethys Sea cutting a wide swath between what would become Europe and Africa. North America was drifting away from Europe, while South America and Africa were beginning their own slow dance of separation. This wasn’t just a simple crack in the ground – we’re talking about oceanic barriers hundreds or even thousands of miles wide.

Ocean Barriers Were Dinosaur Death Traps

The expanding Atlantic Ocean during the Jurassic wasn’t some narrow stream that adventurous dinosaurs could wade across. These were deep, turbulent waters stretching for thousands of miles, presenting an absolutely insurmountable obstacle for land-dwelling creatures. Even the largest dinosaurs, despite their impressive size, were fundamentally terrestrial animals with no adaptations for ocean travel.

Consider the logistics: a 30-ton Brontosaurus would need to somehow swim across an ocean wider than the modern Atlantic. The very idea defies everything we know about dinosaur physiology and behavior. Their massive bodies, designed for supporting weight on land, would have been utterly helpless in deep water.

The few dinosaurs that lived near coastlines would have faced additional challenges beyond just the distance. Ocean currents, storms, and the complete absence of food sources during such a journey would have made any attempted crossing a suicide mission.

Continental Drift Speed Made Migration Impossible

Some might wonder if dinosaurs could have simply walked across land bridges before the continents separated too far. The timing, however, makes this scenario completely impossible. Continental drift operates on geological timescales that dwarf even the longest dinosaur lifespans.

The separation between continents was progressing at a rate of just a few centimeters per year – about as fast as your fingernails grow. This means that even over millions of years, the gaps between landmasses were already too wide for any terrestrial animal to cross by the time most Jurassic dinosaurs evolved.

By the middle Jurassic, roughly 170 million years ago, the continental positions had shifted enough that direct land connections between major landmasses were already ancient history. The dinosaurs we know and love from this period were born into a world where intercontinental travel was simply not an option.

Fossil Evidence Reveals Isolated Ecosystems

The fossil record provides compelling evidence that dinosaur populations were indeed isolated on their respective continents. When paleontologists examine Jurassic dinosaur fossils from different continents, they find distinct regional differences that could only have developed through prolonged isolation.

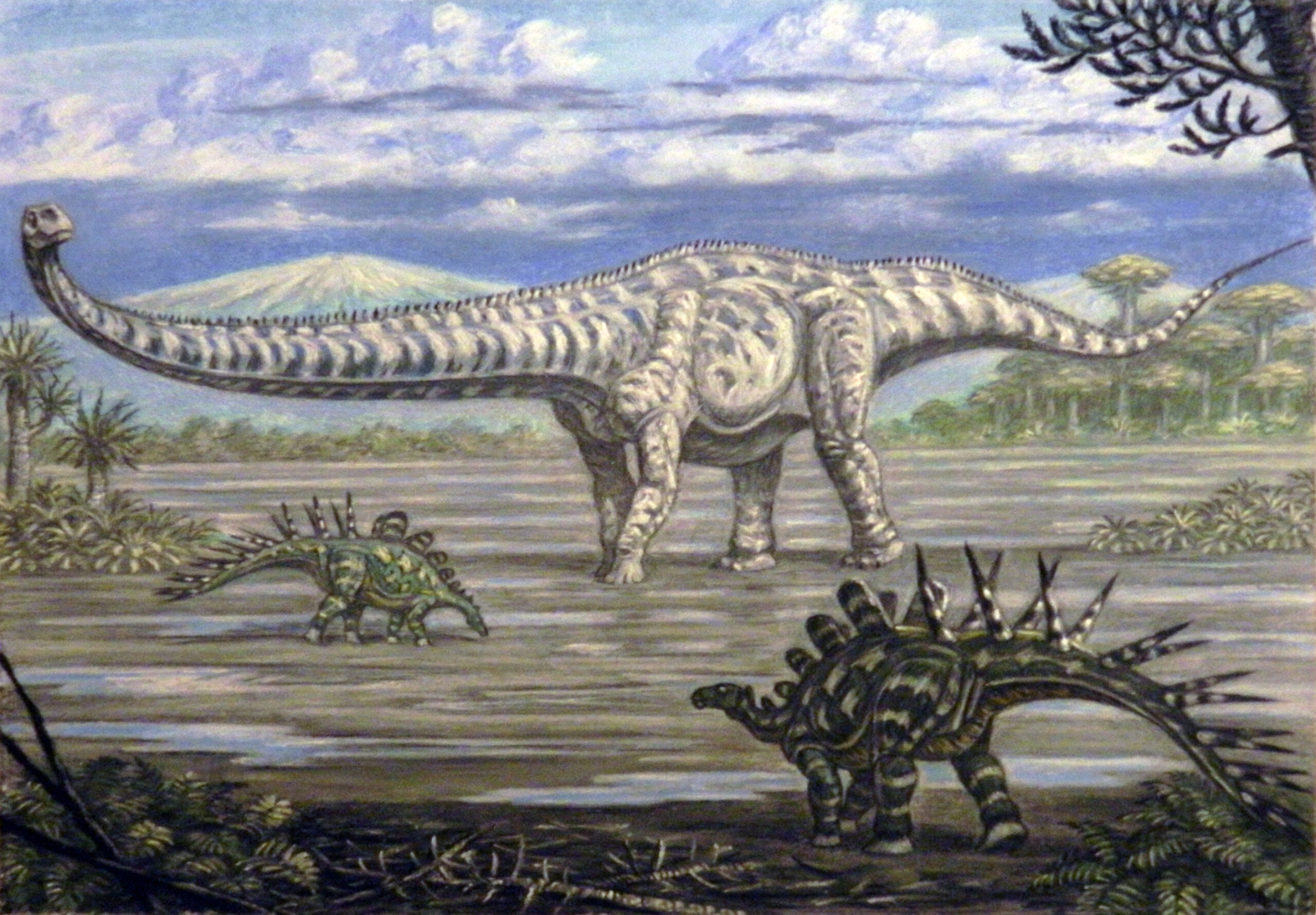

North American Jurassic sites like the Morrison Formation yield dinosaurs like Allosaurus, Diplodocus, and Stegosaurus – species that are completely absent from contemporary sites in Europe or Asia. Meanwhile, Chinese formations from the same period contain unique species like Mamenchisaurus and Sinraptor that never appear in Western fossil beds.

This pattern isn’t just a quirk of fossil preservation. It represents genuine biological isolation where dinosaur populations evolved separately for millions of years. If intercontinental migration had been possible, we would expect to see much more similarity between dinosaur faunas from different continents.

The Morrison Formation: A North American Time Capsule

The Morrison Formation, stretching across the western United States, offers one of the most complete pictures of Jurassic dinosaur life anywhere in the world. This massive geological formation, deposited between 156 and 145 million years ago, contains fossils of dozens of dinosaur species that lived in splendid isolation from the rest of the world.

What makes the Morrison Formation so fascinating is its incredible diversity of uniquely North American dinosaurs. From the club-tailed Stegosaurus to the enormous Diplodocus, these animals evolved characteristics that set them apart from their contemporaries on other continents. The long-necked sauropods of North America, for instance, developed different feeding strategies and body proportions compared to their relatives in South America and Africa.

The isolation is so complete that even closely related dinosaur families show distinct evolutionary paths. The theropod dinosaurs of North America, dominated by Allosaurus and its relatives, evolved hunting strategies and physical features that differed markedly from the theropods flourishing in China during the same period.

European Dinosaurs Tell Their Own Story

While North America was developing its distinctive dinosaur fauna, Europe was following its own evolutionary path. The European Jurassic fossil record, though less extensive than North America’s, reveals a completely different cast of characters adapted to the unique conditions of their isolated continent.

European sites have yielded dinosaurs like Cetiosaurus, one of the first sauropods to be scientifically described, and Megalosaurus, a massive theropod that ruled European ecosystems. These dinosaurs show no direct relationship to their North American contemporaries, despite living at exactly the same time in Earth’s history.

The differences extend beyond just species names. European dinosaurs adapted to different climates, vegetation, and ecological niches than their isolated relatives on other continents. This separate evolutionary trajectory could only have occurred if the dinosaur populations were completely cut off from genetic exchange with other continents.

Asian Dinosaurs: Masters of Their Own Domain

Asia during the Jurassic period was perhaps the most isolated of all the major landmasses, and its dinosaur fossils reflect this extreme separation. Chinese fossil sites from the Jurassic period have revealed some of the most unique and specialized dinosaurs ever discovered, many of which evolved characteristics seen nowhere else in the world.

Mamenchisaurus, with its impossibly long neck stretching up to 35 feet, represents an evolutionary experiment that occurred only in Asia. This massive sauropod developed neck proportions that far exceeded anything found in North America or Europe, suggesting that Asian dinosaurs faced unique environmental pressures that drove their evolution in different directions.

The theropod dinosaurs of Asia also tell a story of isolation. Species like Yangchuanosaurus developed hunting strategies and physical features that differed significantly from their North American and European relatives, despite filling similar ecological roles as apex predators.

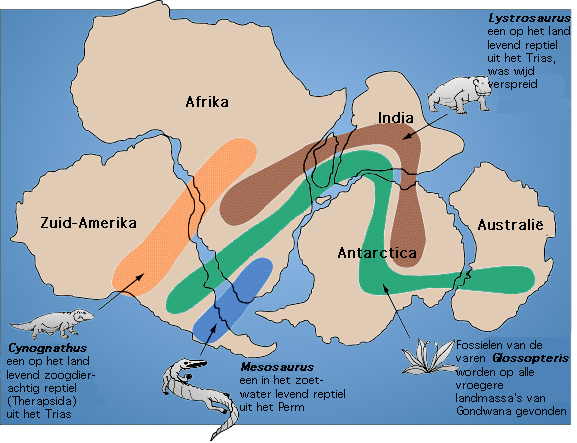

South American Dinosaurs: The Gondwana Connection

South America during the Jurassic period was still connected to Africa as part of the southern supercontinent Gondwana, but even this connection was becoming increasingly tenuous. The dinosaur fossils from South America show some similarities to African species, but also reveal a growing divergence as the two continents began their slow separation.

The sauropod dinosaurs of South America evolved some of the most extreme adaptations seen anywhere in the world. These giants developed feeding strategies and body proportions that were uniquely suited to the vegetation and climate of their isolated continent, setting the stage for the even more spectacular dinosaurs that would evolve there during the Cretaceous period.

What’s particularly interesting about South American Jurassic dinosaurs is how they represent a transitional phase. Early in the period, they showed more similarities to African dinosaurs, but as the Atlantic Ocean continued to widen, the South American dinosaur fauna became increasingly distinct and specialized.

The Role of Climate in Dinosaur Isolation

The separation of continents during the Jurassic didn’t just create physical barriers – it also led to the development of distinct climate zones that would have made intercontinental migration impossible even if land bridges had existed. Each isolated continent developed its own unique weather patterns, seasonal cycles, and vegetation communities.

North America during the Jurassic experienced a warm, seasonal climate with distinct wet and dry periods. The dinosaurs that evolved there became adapted to these specific conditions, developing behaviors and physical characteristics that wouldn’t have been suitable for survival on other continents with different climates.

Asian dinosaurs, meanwhile, adapted to monsoon-like conditions with heavy seasonal rainfall. The vegetation and ecosystem structure that resulted from this climate created evolutionary pressures that were completely different from those faced by dinosaurs on other continents, leading to the development of unique species that couldn’t have survived elsewhere.

Vegetation Barriers: Different Plants, Different Dinosaurs

The isolation of continents during the Jurassic period led to the evolution of distinct plant communities on each landmass, creating another layer of barriers that would have prevented successful dinosaur migration. Herbivorous dinosaurs, in particular, evolved specialized digestive systems and feeding behaviors adapted to the specific plants available on their home continents.

North American dinosaurs fed primarily on conifers, ferns, and cycads that had evolved in the unique climate conditions of the isolated continent. Their digestive systems became finely tuned to extract nutrients from these specific plants, making them unable to survive on the different vegetation that had evolved on other continents.

The sauropods of different continents provide a perfect example of this specialization. While all sauropods were herbivores, those in North America evolved different neck structures and feeding strategies compared to their relatives in Asia or South America, reflecting the unique plant communities they needed to exploit for survival.

Ocean Currents: The Invisible Walls

Even if some dinosaurs had been capable swimmers, the ocean currents of the Jurassic period would have created additional barriers to intercontinental movement. The newly forming Atlantic Ocean generated powerful current systems that would have swept any struggling dinosaur far off course, making directed migration between continents virtually impossible.

The warm, shallow seas that covered much of the continental margins during the Jurassic were also home to massive marine reptiles like plesiosaurs and ichthyosaurs. These apex predators of the ocean would have made any attempted water crossing by terrestrial dinosaurs an extremely dangerous proposition, adding another layer of discouragement to intercontinental travel.

The current systems also affected climate patterns on each continent, reinforcing the development of distinct ecological zones that would have made successful colonization of new continents difficult even if individual dinosaurs had somehow managed to cross the oceans.

Genetic Evidence in Modern Descendants

Modern genetic studies of birds – the direct descendants of dinosaurs – provide additional evidence for the isolation of Jurassic dinosaur populations. The genetic divergence seen in modern bird populations reflects separation events that occurred during the Mesozoic Era, when their dinosaur ancestors were trapped on isolated continents.

The molecular clock evidence suggests that major lineages of dinosaurs diverged at times that correspond perfectly with the breakup of Pangaea. This genetic evidence provides a timestamp for when different dinosaur populations lost contact with each other, confirming that intercontinental migration was impossible during the Jurassic period.

The geographic distribution of modern bird families also reflects the ancient continental positions during the Jurassic. Certain bird lineages are found only in regions that correspond to the isolated landmasses where their dinosaur ancestors evolved, providing a living reminder of the barriers that separated dinosaur populations millions of years ago.

The Impossible Physics of Dinosaur Ocean Crossing

From a purely physical standpoint, the idea of dinosaurs crossing oceans becomes even more absurd when we consider the biomechanics involved. Large dinosaurs like sauropods had body densities that would have made them sink like stones in water, while their massive size would have made swimming energetically impossible.

Even smaller dinosaurs would have faced insurmountable challenges. The energy requirements for swimming across thousands of miles of open ocean would have exceeded the metabolic capabilities of any dinosaur, regardless of their size or physical condition. The absence of food sources during such a journey would have made the endeavor literally impossible.

The bone structure of dinosaurs also tells us that they were completely adapted for terrestrial life. Their heavy, solid bones were designed to support massive weights on land, not to provide buoyancy in water. This fundamental aspect of dinosaur anatomy makes ocean crossing physically impossible.

Lessons from Island Biogeography

Modern studies of island biogeography provide perfect examples of how geographic isolation leads to the evolution of distinct species, exactly as we see in the Jurassic dinosaur fossil record. Islands separated by just a few miles of water often develop completely different species over relatively short periods of time.

The Galápagos Islands, separated by only narrow channels of water, host different species of finches on each island despite their proximity. If small birds can’t regularly cross such minor water barriers, it becomes absurd to imagine massive dinosaurs crossing entire oceans during the Jurassic period.

Madagascar, separated from Africa by the Mozambique Channel, developed a completely unique fauna that includes no large terrestrial mammals. This isolation occurred over a much shorter timescale than the separation of Jurassic continents, yet it was sufficient to prevent the colonization of large land animals. The implications for dinosaur intercontinental migration are clear.

The evidence from geology, paleontology, and modern biology all points to the same inescapable conclusion: dinosaurs were prisoners of their own continents during the Jurassic period. The vast oceans that separated the fragmenting pieces of Pangaea created barriers that were simply too wide, too deep, and too hostile for any terrestrial animal to cross. Each continent became an isolated evolutionary laboratory where dinosaurs developed unique characteristics that reflected their specific environments and ecological challenges. The incredible diversity of dinosaur species we see in the fossil record wasn’t the result of global migration and mixing – it was the product of millions of years of separation and independent evolution. What would you have expected from creatures that ruled the Earth yet couldn’t swim across an ocean?