Picture London’s Thames River completely frozen solid, with massive frost fairs taking place on its icy surface. Imagine Alpine glaciers advancing so far they swallowed entire villages, leaving nothing but legends of lost communities beneath the ice. From roughly 1300 to 1850, Europe experienced one of the most dramatic climate shifts in recorded history – a period so severe it earned the name “The Little Ice Age.” This wasn’t just a minor temperature drop; it was a climatic catastrophe that reshaped entire civilizations, triggered famines, sparked wars, and fundamentally altered the course of human history.

The Great Cooling Begins

The Little Ice Age didn’t arrive overnight like a sudden winter storm. Instead, it crept across Europe gradually, beginning around 1300 and lasting until approximately 1850. During this period, average temperatures dropped by just 1-2 degrees Celsius, but this seemingly small change had devastating consequences.

The cooling began during what historians call the Medieval Warm Period’s end, when favorable conditions had allowed Viking settlements in Greenland and robust agriculture across northern Europe. As temperatures began their steady decline, the first signs appeared in mountain regions where glaciers started their relentless advance. By the 14th century, the cooling had become unmistakable, ushering in an era that would test human resilience like never before.

When Rivers Turned to Ice Highways

The Thames River in London became a symbol of just how extreme the Little Ice Age could be. Between 1608 and 1814, the Thames froze solid at least 23 times, creating natural ice highways that could support entire festivals. These “Frost Fairs” became legendary events where merchants set up shops, people played games, and entire communities gathered on the frozen river.

Similar scenes played out across northern Europe. The canals of Amsterdam became solid ice paths, while the Baltic Sea froze so completely that armies could march across it. In 1658, Swedish forces famously crossed the frozen sea to attack Copenhagen, using the ice as their highway to victory. Rivers that had flowed freely for centuries suddenly became frozen monuments to nature’s power.

The frozen waterways weren’t just curiosities – they were lifelines. Transportation routes that typically relied on boats had to adapt quickly, and communities learned to use the ice as natural bridges and highways during the harshest months.

The Agricultural Apocalypse

For medieval Europe, agriculture was everything, and the Little Ice Age struck at the very heart of survival. Growing seasons shortened dramatically, sometimes by as much as two months. Crops that had thrived for generations suddenly failed year after year, creating a cascade of hunger and desperation.

The situation was particularly devastating in northern regions where grain production plummeted. Wheat harvests in England dropped by up to 20% compared to earlier periods, while in Scandinavia, entire farming regions had to be abandoned. The potato, which wouldn’t arrive in Europe until the 16th century, became crucial for survival because it could grow in the cooler, wetter conditions.

Vineyards that had flourished as far north as England disappeared entirely. The wine industry, which had been a cornerstone of medieval economy, retreated hundreds of miles south. Even today, the northern limits of wine production haven’t fully recovered to their medieval extent.

Famine: The Invisible Killer

The Great Famine of 1315-1322 stands as one of history’s most devastating hunger crises, directly linked to the Little Ice Age’s onset. Across Europe, millions died as crops failed repeatedly and livestock perished in the harsh conditions. Chronicles from the time describe people eating bark, roots, and even resorting to cannibalism in the most desperate circumstances.

Ireland suffered particularly severely, with contemporary accounts describing fields turned to muddy swamps and grain rotting before it could be harvested. The population of Europe may have declined by as much as 25% during the worst famine years. Cities became death traps as rural populations fled to urban centers, only to find no food there either.

These famines weren’t isolated events but recurring nightmares that haunted European communities for centuries. Each failed harvest brought the specter of starvation closer, creating a psychological trauma that influenced everything from religious practices to political structures.

Glaciers on the March

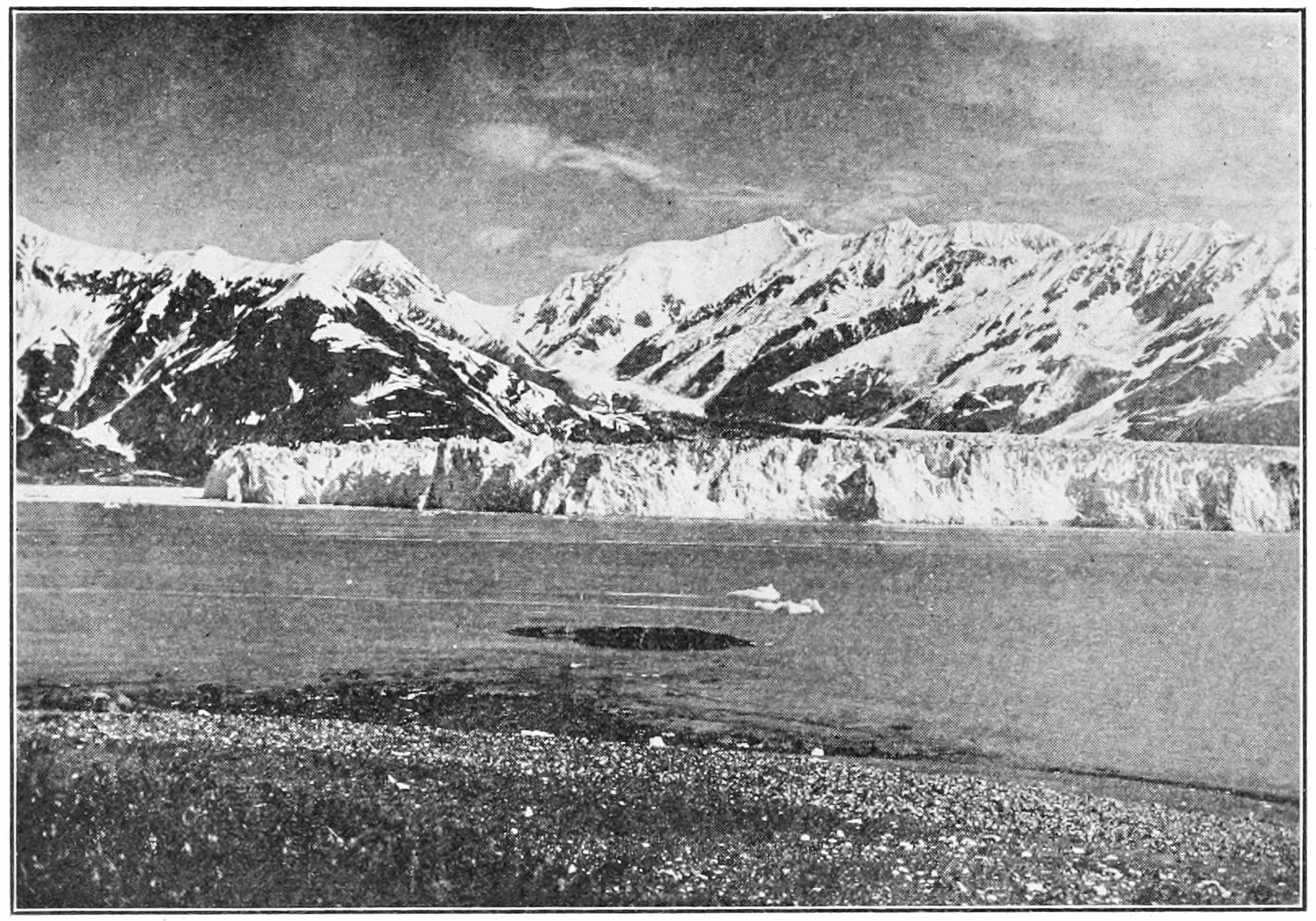

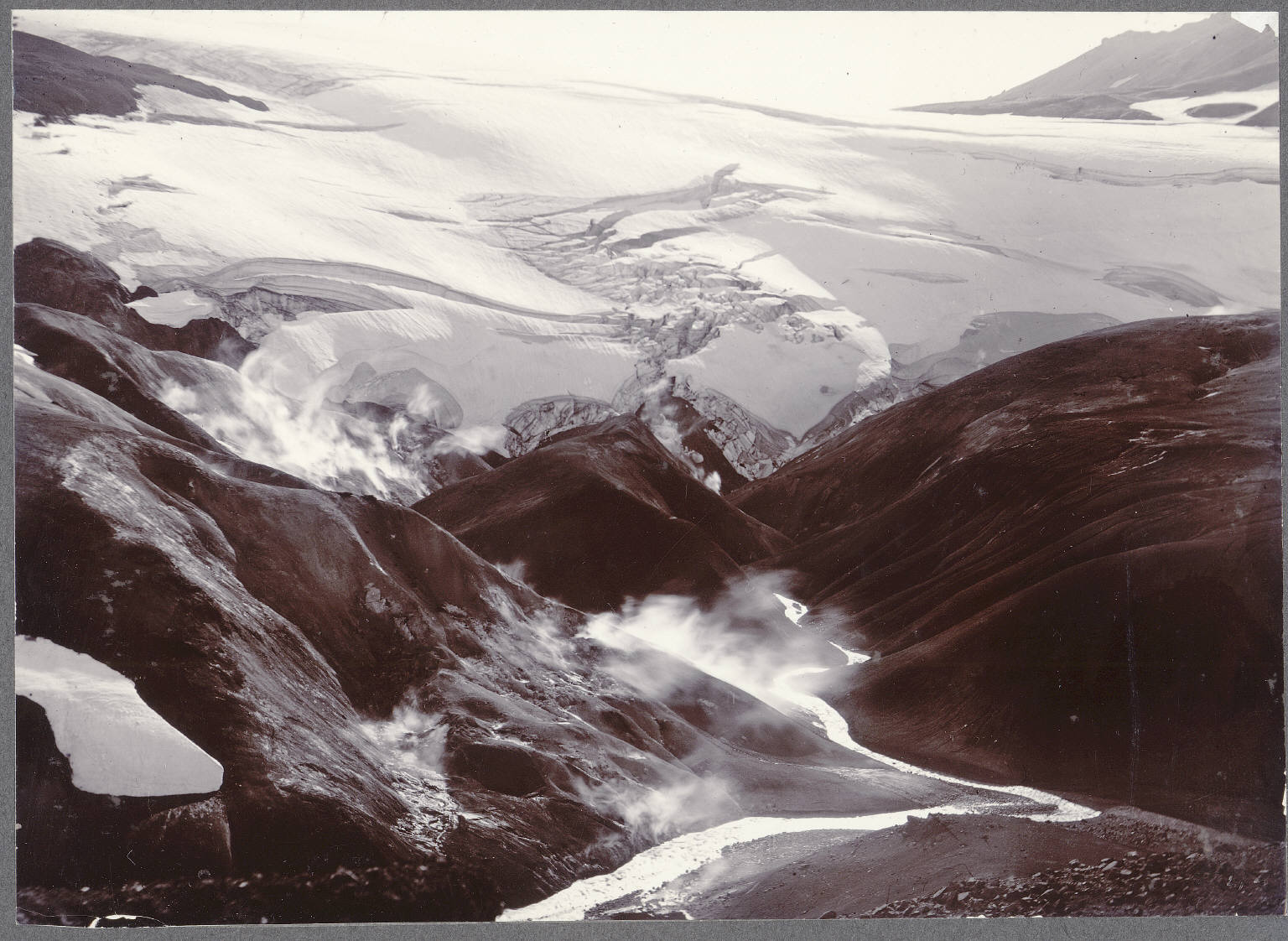

Perhaps no feature of the Little Ice Age was more visually dramatic than the advancing glaciers. Alpine glaciers pushed forward with unstoppable force, consuming forests, farms, and entire villages in their path. The Chamonix valley in France watched helplessly as glaciers advanced over 1,000 meters beyond their previous limits.

In Switzerland, the village of Grindelwald faced a terrifying wall of ice that seemed to grow closer each year. Local church records describe prayers and processions aimed at stopping the glacial advance, reflecting the desperate helplessness communities felt. Some villages were completely abandoned as residents fled the approaching ice.

The glacial advance wasn’t uniform or predictable. Some glaciers surged forward rapidly, while others crept slowly but relentlessly. This unpredictability made it impossible for communities to plan or adapt, leading to a constant state of anxiety about when the ice might claim their homes.

The Black Death’s Climate Connection

The devastating Black Death that swept through Europe in the 14th century found perfect conditions in the Little Ice Age’s early stages. Cooler, wetter weather created ideal breeding conditions for the fleas that carried plague bacteria, while weakened populations suffering from repeated famines had little resistance to disease.

The plague’s spread was facilitated by the climate chaos of the time. Trade routes disrupted by weather changes concentrated people in unsanitary conditions, while malnutrition from failed harvests made entire populations vulnerable. The combination of climatic stress and disease created a perfect storm of mortality.

Some historians argue that without the Little Ice Age’s agricultural failures, the Black Death might never have achieved such devastating scope. The climate didn’t cause the plague, but it certainly created the conditions that allowed it to flourish and spread with unprecedented speed.

Social Upheaval and Witch Hunts

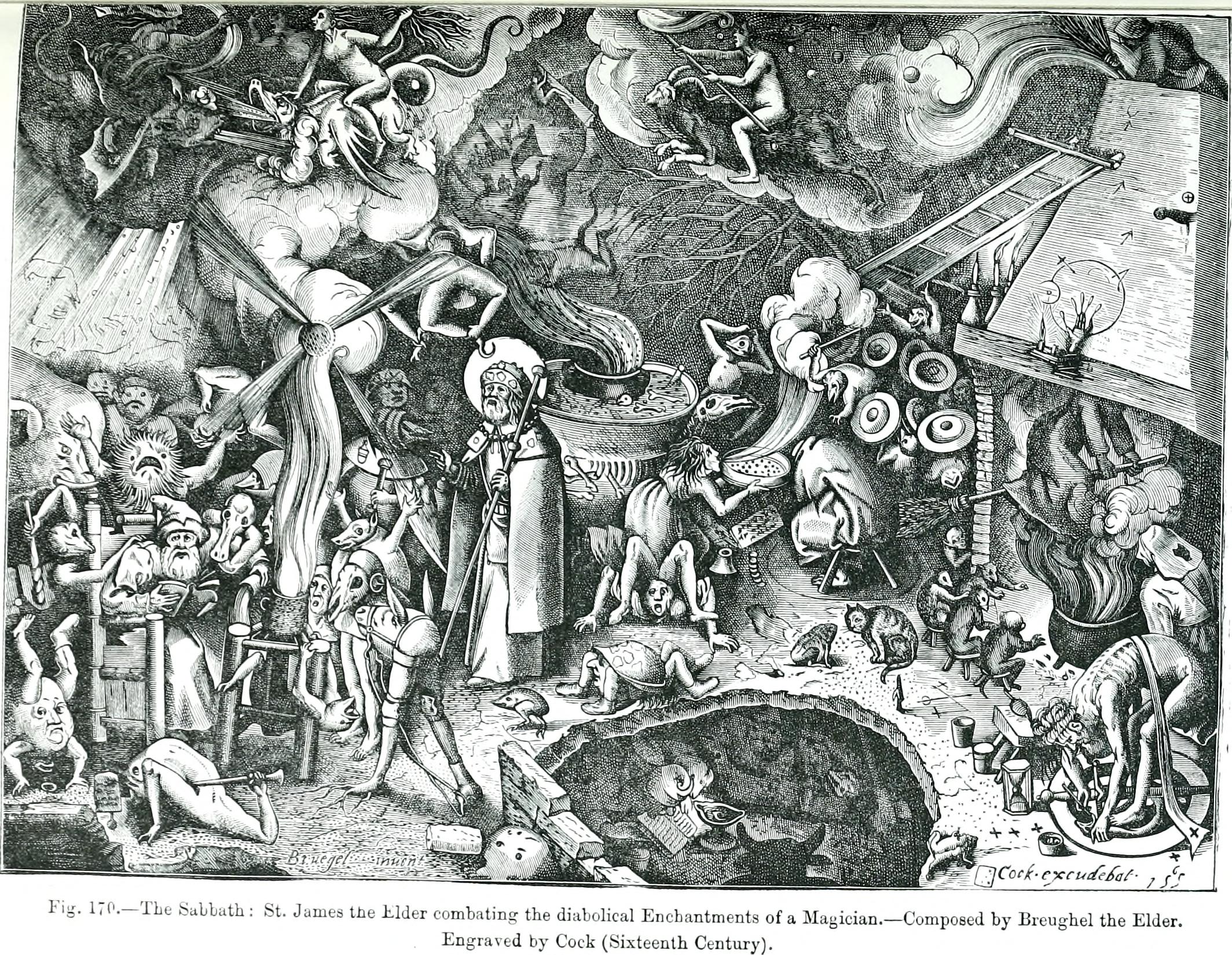

The Little Ice Age didn’t just change the physical landscape – it transformed European society in profound and often dark ways. As communities struggled with repeated crop failures and unexplained climate chaos, they sought scapegoats for their suffering. This period coincided with the most intense phase of European witch hunts.

Between 1580 and 1650, during some of the coldest decades of the Little Ice Age, witch trials reached their peak intensity. Communities desperate for explanations for their suffering turned to supernatural causes, often targeting vulnerable women as the source of their climate-related misfortunes. The correlation between the coldest years and the most intense persecutions is striking.

Social structures that had maintained stability for centuries began to crumble under the pressure. Peasant revolts became more common as traditional feudal relationships broke down under the stress of repeated harvest failures and economic disruption.

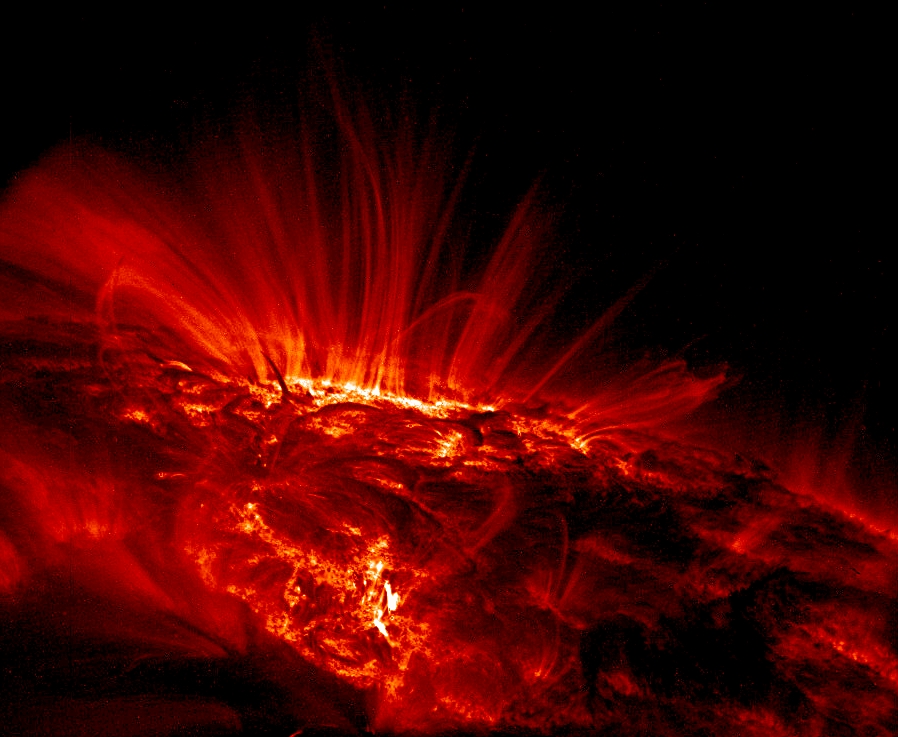

The Sun’s Mysterious Silence

Modern science has revealed a fascinating connection between the Little Ice Age and unusual solar activity. During the period from 1645 to 1715, known as the Maunder Minimum, sunspots virtually disappeared from the sun’s surface. This period of solar quiet coincided with some of the coldest decades of the Little Ice Age.

Astronomers of the time, armed with newly invented telescopes, documented this strange solar behavior. The absence of sunspots suggested reduced solar activity, which scientists now believe contributed to the cooling climate. This wasn’t the only period of solar quiet during the Little Ice Age – several other minimums occurred, each correlating with particularly harsh winters.

The solar connection helps explain why the Little Ice Age was a global phenomenon, not just a European one. While Europe experienced the most dramatic effects, cooling occurred worldwide, suggesting a truly astronomical cause rather than just regional climate variations.

Volcanic Winters and Atmospheric Chaos

Massive volcanic eruptions added another layer of chaos to the Little Ice Age’s climate disruption. The 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia created what became known as “The Year Without a Summer” in 1816. Ash and sulfur dioxide in the atmosphere blocked sunlight, causing global temperatures to plummet even further.

Europe experienced some of its coldest weather ever recorded during this volcanic winter. Snow fell in June across much of the continent, while crops failed spectacularly. The combination of volcanic cooling on top of the already cold Little Ice Age conditions created a climate catastrophe that influenced everything from literature to migration patterns.

Other eruptions throughout the period contributed to the cooling, creating a feedback loop where each volcanic event made the existing cold conditions worse. The 1783 Laki eruption in Iceland poisoned the atmosphere with sulfur, causing additional cooling and crop failures across Europe.

Art and Literature Born from Ice

The Little Ice Age profoundly influenced European art and literature, creating works that still resonate today. Dutch painters of the 17th century captured the frozen landscapes in stunning detail, giving us visual records of just how different the climate was. Pieter Bruegel’s winter scenes weren’t artistic imagination – they were documentation of reality.

Literature of the period reflects the harsh conditions and social upheaval. The themes of survival, hardship, and nature’s power that characterize much medieval and early modern literature directly stem from the lived experience of the Little Ice Age. Even fairy tales from this period often involve harsh winters and food scarcity.

The period’s art serves as invaluable climate documentation. Paintings showing frozen rivers, snow-covered landscapes, and winter activities provide scientists with crucial evidence about past climate conditions. These artistic records complement written accounts and help scientists understand the full scope of the climate change.

Innovation Born from Desperation

Necessity truly became the mother of invention during the Little Ice Age. Communities facing repeated crop failures developed new agricultural techniques, including improved crop rotation and the adoption of new crops like potatoes and maize from the Americas. These innovations helped populations survive the harsh conditions.

Heating technology advanced rapidly as communities struggled to stay warm. The development of more efficient stoves, better insulation techniques, and improved building design all emerged from the desperate need to conserve heat. These innovations would later contribute to the Industrial Revolution.

Food preservation techniques also evolved rapidly during this period. Methods for storing grain, preserving meat, and extending the shelf life of various foods became crucial survival skills. Many traditional preservation methods still used today were refined during the Little Ice Age out of absolute necessity.

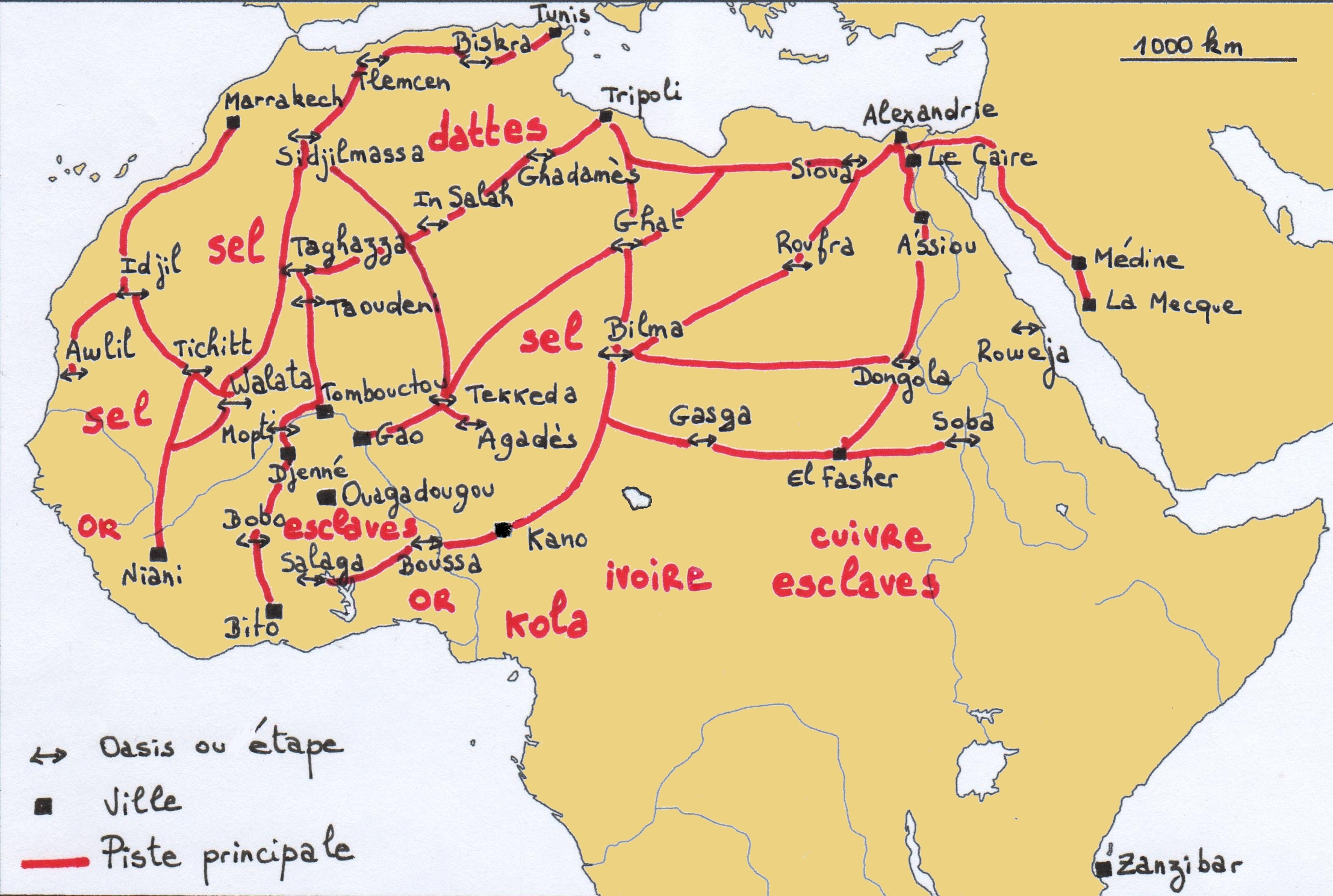

The Economics of Survival

The Little Ice Age fundamentally altered European economic systems. Traditional agriculture-based economies had to adapt or collapse, leading to the development of new trade relationships and economic structures. The need to import grain from warmer regions created new trade routes and commercial relationships.

Urban centers began to play increasingly important roles as rural agriculture became less reliable. Cities offered alternative livelihoods and became centers of innovation and adaptation. This shift contributed to the rise of merchant classes and the development of more sophisticated financial systems.

The period also saw the emergence of new industries adapted to the harsh conditions. Fur trading expanded dramatically as demand for warm clothing increased. The production of alcohol, which provided calories and warmth, became an important economic activity in many regions.

The Great Thaw and Modern Warming

The Little Ice Age began to end around 1850, with temperatures gradually returning to more normal levels. This warming wasn’t uniform – it occurred in fits and starts, with some regions warming faster than others. The end of the period coincided with the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, though the relationship between these two events remains debated.

The thaw revealed landscapes that had been hidden under ice for centuries. Villages that had been abandoned to advancing glaciers were rediscovered, often perfectly preserved in the ice. Archaeological sites that had been covered for hundreds of years emerged, providing new insights into medieval life.

Today’s climate scientists study the Little Ice Age as a crucial example of how relatively small temperature changes can have massive societal impacts. The period serves as a sobering reminder of human vulnerability to climate change and the importance of adaptation strategies.

The Little Ice Age stands as one of history’s most dramatic examples of how climate can reshape civilization. For over 500 years, Europe endured conditions that would challenge modern society, yet communities adapted, innovated, and ultimately survived. The period’s legacy lives on in our art, literature, and collective memory, while its lessons about climate adaptation remain more relevant than ever. As we face our own climate challenges, the resilience and ingenuity displayed during those frozen centuries offer both inspiration and sobering perspective on humanity’s relationship with our changing planet. What other hidden chapters of climate history might hold keys to understanding our future?