For millions of years, dinosaurs ruled Earth, but until recently, their parenting behaviors remained shrouded in mystery. Thanks to remarkable fossil discoveries and advanced scientific techniques, paleontologists have begun piecing together compelling evidence of dinosaur parenting. From nest structures to growth patterns in fossilized bones, these ancient reptiles appear to have exhibited surprising levels of parental care, challenging long-held assumptions about their behavior. This article explores the fascinating fossil evidence that reveals how dinosaurs may have nurtured, protected, and raised their offspring in a prehistoric world filled with dangers.

Nest Discoveries: The First Clues to Dinosaur Parenting

One of the most significant breakthroughs in understanding dinosaur parenting came with the discovery of fossilized nests around the world. In Montana’s Two Medicine Formation, paleontologist Jack Horner uncovered Maiasaura (“good mother lizard”) nests containing remains of both eggs and hatchlings. These nests, dating back 75 million years, were spaced approximately 23 feet apart, suggesting an organized nesting colony. The nest structures themselves—bowl-shaped depressions about 6-8 feet in diameter—contained evidence of organic material that likely served as plant matter to keep eggs warm. Perhaps most tellingly, the worn teeth of hatchlings found within the nests indicated they remained in the nest after hatching, suggesting they were fed by parents rather than leaving immediately to fend for themselves.

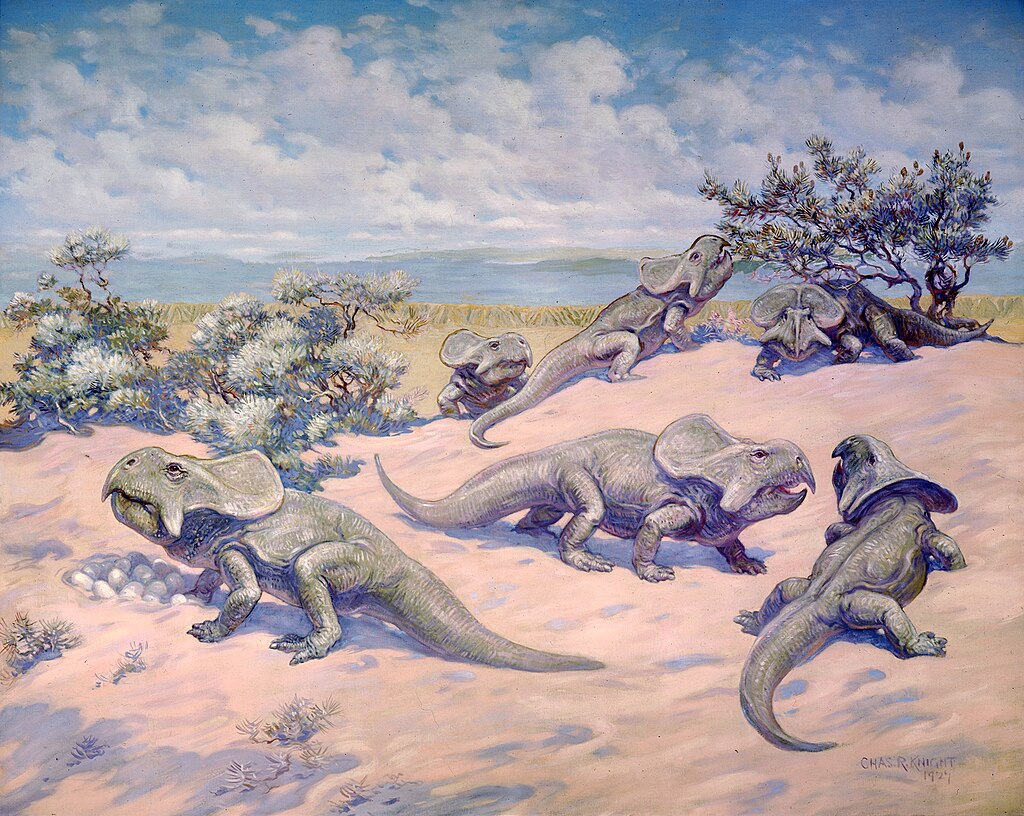

Oviraptor: From “Egg Thief” to Devoted Parent

Few fossil discoveries have transformed our understanding of dinosaur parenting more dramatically than the misnamed Oviraptor. Originally labeled an “egg thief” when discovered by Roy Chapman Andrews in 1923 atop what appeared to be a Protoceratops nest, this dinosaur’s reputation underwent a complete rehabilitation decades later. In the 1990s, additional fossils revealed these Oviraptors weren’t stealing eggs—they were protecting their own. Multiple specimens have been found in brooding positions identical to modern birds, with their limbs symmetrically arranged around clutches of eggs, some with embryos that were genetically related to the adult. One particularly poignant specimen discovered in the Gobi Desert shows an adult that apparently died in a sandstorm while shielding its nest, steadfastly remaining in position as the sand engulfed it, a testament to parental dedication that lasted 75 million years.

Embryonic Development and Nurturing Evidence

The study of dinosaur embryos has provided crucial insights into how these creatures may have cared for their developing young. Advanced imaging techniques have allowed paleontologists to examine embryos within fossilized eggs without breaking them, revealing developmental stages that suggest different hatching timelines across dinosaur species. Some theropod dinosaurs like Troodon appear to have had extended incubation periods of up to 70 days, significantly longer than similarly sized reptiles today. This extended development suggests hatchlings were more mature when they emerged, but likely still required parental care. In contrast, sauropod eggs show evidence of rapid embryonic development with less mature hatchlings that possibly needed less direct care but perhaps protection within herds. The varying developmental patterns across dinosaur families indicate diverse parenting strategies evolved to suit different ecological niches and survival requirements.

Growth Rate Analysis: Evidence of Extended Care

Bone histology—the microscopic study of bone structure—has revolutionized our understanding of dinosaur growth patterns and, by extension, parenting behaviors. By examining growth rings in fossilized bones (similar to tree rings), scientists can determine how quickly dinosaurs grew and when they reached maturity. Research on Maiasaura bones shows hatchlings grew rapidly in their first year, suggesting they received substantial nutrition that would be difficult to obtain without parental provisioning. Studies of other dinosaur species reveal varying growth rates, with some species showing evidence of growth spurts followed by plateaus, potentially indicating transitions from parental dependence to independence. These growth signatures differ significantly from those of reptiles, which typically grow slowly and steadily, and more closely resemble the rapid growth patterns seen in birds with attentive parental care.

Trackway Evidence: Family Dynamics in Motion

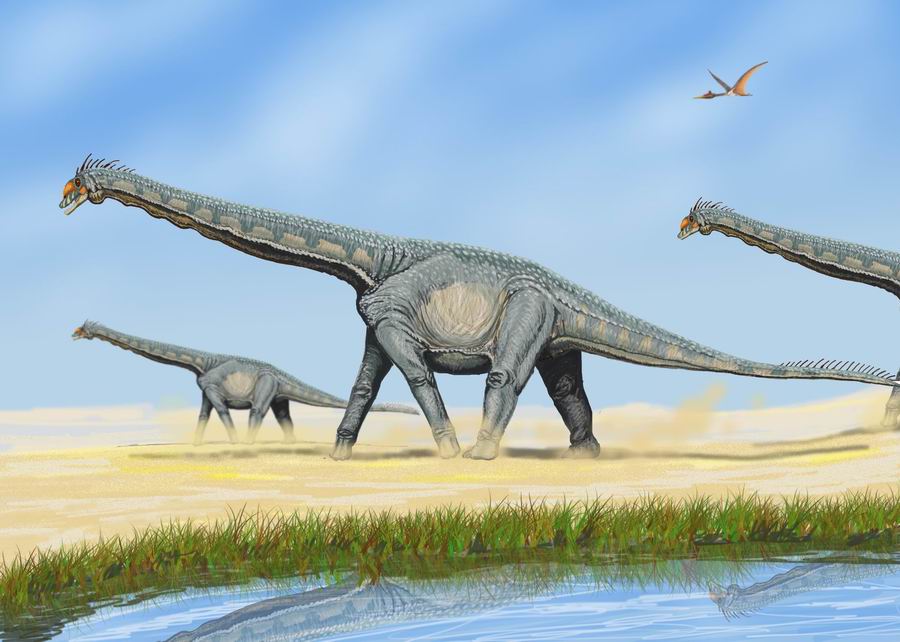

Fossilized footprints provide rare glimpses into dinosaur behavior that skeletal remains alone cannot reveal. Multiple trackway sites around the world show evidence of adults walking alongside smaller individuals of the same species, suggesting family groups traveling together. In South Korea, a remarkable set of tracks displays an adult sauropod moving alongside multiple juveniles, all headed in the same direction, with the smaller tracks positioned protectively between the larger ones. In British Columbia, trackways reveal multiple generations of hadrosaurs moving together, with footprints showing consistent spacing that suggests coordinated movement. The consistent association of different-sized footprints across various dinosaur families indicates that many species likely traveled in family groups, with adults potentially providing protection and guidance to younger individuals during migrations or daily activities.

Communal Nesting: Social Parenting Structures

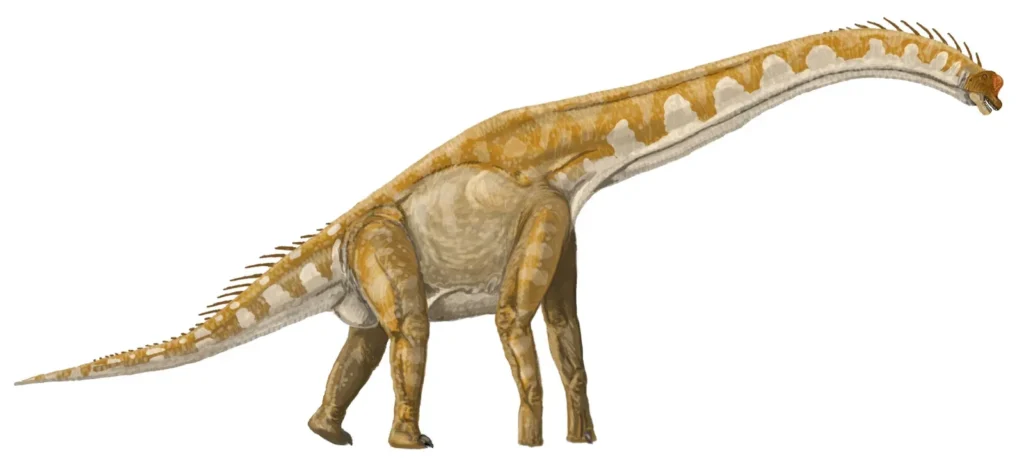

Multiple fossil sites have uncovered evidence of communal nesting behaviors among certain dinosaur species, suggesting complex social structures devoted to offspring care. The “Egg Mountain” site in Montana reveals hundreds of Maiasaura nests in close proximity, carefully spaced to allow adult access while maintaining a dense colony that would offer protection from predators. Similar colonial nesting patterns have been discovered for Argentina’s Massospondylus and China’s Lufengosaurus, with dozens of nests containing eggs at similar developmental stages, indicating synchronized breeding seasons. These communal nesting grounds mirror behaviors seen in modern birds like flamingos or penguins, where parents can share vigilance duties against predators. The organization of these nesting colonies suggests sophisticated social behaviors far beyond what was once attributed to dinosaurs, potentially including cooperative defense and possibly even crèche structures where adults might have supervised multiple juveniles.

Feeding the Young: Dietary Evidence in Fossils

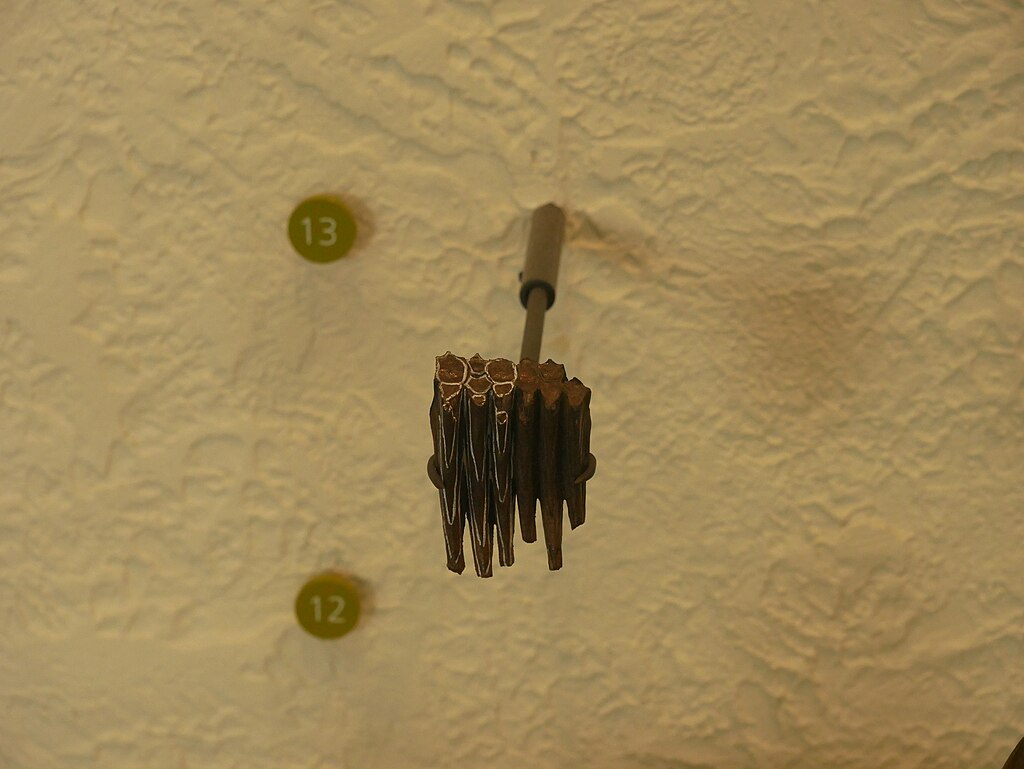

How dinosaurs fed their young remains among the most fascinating questions in paleontology, with several lines of evidence providing clues. Microscopic wear patterns on the teeth of juvenile hadrosaurs differ from adults, suggesting they consumed softer vegetation, possibly pre-processed or selected by parents. In some theropod nests, researchers have found remains of small prey animals positioned near hatchlings, potentially representing food brought by parents similar to how modern birds provision their chicks. The digestive tracts of exceptionally preserved juvenile specimens occasionally contain food remnants different from what adults typically consumed, suggesting specialized juvenile diets that may have required parental selection. Perhaps most compelling is evidence from a juvenile Maiasaura whose leg bones showed growth rates impossible to achieve without substantial nutrition, indicating either direct feeding by parents or at minimum, guidance to rich food sources during a critical growth period.

Altricial vs. Precocial Young: Different Parenting Strategies

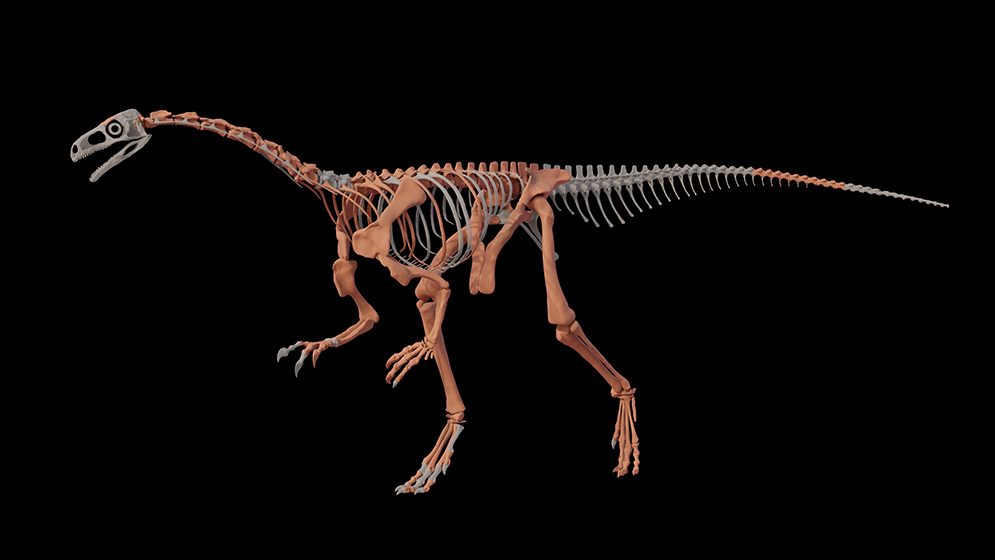

The fossil record reveals dinosaurs evolved diverse parenting strategies tailored to their ecological niches, broadly falling into patterns resembling either altricial care (helpless young requiring extensive parenting) or precocial development (relatively independent hatchlings). Small theropods like Troodon produced fewer, larger eggs with more developed embryos, suggesting altricial young that required extended care similar to modern birds. Bone studies of these hatchlings show they weren’t immediately capable of independent locomotion, further indicating parental dependence. In contrast, sauropod dinosaurs laid many smaller eggs, and trackway evidence suggests their hatchlings could move independently soon after emergence, though they likely remained within the protection of herds. These differences parallel modern animals, where species facing greater predation pressure often evolve more precocial offspring, while those capable of defending nests frequently develop more intensive parenting strategies for fewer, more dependent young.

Temperature Regulation: Nurturing Through Incubation

Recent research on dinosaur eggs has yielded surprising insights into how dinosaurs may have regulated nest temperatures to nurture their developing embryos. Using geochemical analysis techniques, scientists can determine the temperature at which eggshell minerals formed, revealing that many dinosaur eggs were maintained at temperatures consistent with active incubation rather than reliance on environmental heat. Studies of oviraptorid and troodontid eggs show they were kept at temperatures between 35-40°C (95-104°F), significantly warmer than ambient environmental temperatures would allow without parental intervention. For larger dinosaurs that couldn’t directly sit on eggs without crushing them, evidence suggests they may have covered nests with vegetation that generated heat through decomposition, similar to modern crocodilians but requiring active maintenance and monitoring. Some hadrosaur nests show evidence of carefully arranged vegetation that would have required adult manipulation to maintain optimal incubation conditions for the developing embryos.

Defense of the Young: Protection Strategies

Protecting vulnerable offspring from predators was undoubtedly a crucial aspect of dinosaur parenting, with fossil evidence suggesting various defensive strategies. The sheer size of adult sauropods and ceratopsians likely deterred potential threats through intimidation alone, with juveniles benefiting from staying close to these living fortresses. Among smaller theropods, the brooding position seen in Oviraptor specimens—with arms spread wide—may have served dual purposes of both warming eggs and presenting a threatening display to potential egg predators. Trackway evidence showing adults positioned on the perimeter of juvenile groups suggests deliberate defensive formations during movement. Perhaps most remarkable is the evidence from Psittacosaurus specimens, where an adult was found fossilized with up to 34 juveniles, suggesting a single adult might have supervised multiple young, similar to modern-day day care systems in some birds and crocodilians, where adults aggressively defend crèches of juveniles from potential threats.

Maiasaura: The Model of Dinosaur Parenting

No dinosaur has contributed more to our understanding of dinosaur parenting than Maiasaura peeblesorum, the “good mother lizard” discovered in Montana in the 1970s. This duck-billed dinosaur provided the first comprehensive evidence of extended parental care in dinosaurs, fundamentally changing scientific perspectives. The Maiasaura nesting grounds preserved both eggs and various growth stages of juveniles, with bone studies showing hatchlings remained nest-bound for at least several weeks after hatching. Growth rate analysis of juvenile bones indicated they grew faster than any modern reptile, at rates only possible with intensive nutrition, likely provided by parents. The nest structure itself shows evidence of being built up and maintained with vegetation, requiring ongoing adult attention. Most significantly, the spacing of nests—close enough for community protection but far enough apart to allow adult access—suggests a sophisticated social breeding structure where parents not only fed and protected their own young but likely participated in colony-wide defensive behaviors against predators.

Modern Bird Connections: Evolutionary Continuity

The discovery that birds are living dinosaurs has profound implications for understanding dinosaur parenting, creating an evolutionary continuity that allows reasonable inferences about extinct dinosaur behaviors. Many parenting behaviors observed in modern birds—from nest construction to brooding positions, food provisioning to protection—are now recognized as inherited from their dinosaur ancestors rather than independently evolved traits. The spectrum of care seen in modern birds, from minimal parenting in megapodes to extended family care in corvids, likely reflects similar diversity that existed among dinosaur species. The specialized brood patches (featherless, blood-vessel-rich skin areas used for egg warming) seen in modern birds likely evolved from similar adaptations in feathered dinosaurs. Careful comparison of skeletal features between dinosaurs and their modern bird descendants reveals remarkable similarities in structures associated with egg-laying and brood care, providing further evidence that many of the nurturing behaviors we observe in today’s birds were already present in their dinosaur forebears millions of years ago.

Conclusion: Rewriting the Narrative of Prehistoric Parenting

The accumulating fossil evidence has fundamentally transformed our understanding of dinosaurs from cold, reptilian creatures to attentive, caring parents. From the brooding Oviraptors that died protecting their nests to the communal nesting grounds of Maiasaura, these discoveries reveal dinosaurs invested significantly in their offspring’s survival through protection, feeding, and teaching. This revised view of dinosaur behavior connects them more closely to their living descendants—birds—and helps explain how these remarkable animals dominated Earth’s ecosystems for over 150 million years. As paleontologists continue to unearth new evidence, the story of dinosaur parenting continues to evolve, revealing prehistoric behaviors perhaps not so different from the nurturing instincts we recognize in many species today.