Imagine stepping into a world where massive predators roamed dense forests, where pterosaurs soared through skies thick with volcanic ash, and where the very ground trembled beneath the feet of creatures that would make today’s elephants look like house cats. This was Earth 66 million years ago, just moments before everything changed forever. The dinosaurs weren’t just surviving in this ancient world—they were thriving in ways that would have shaped our planet’s future in unimaginable directions.

The Final Golden Age of Dinosaur Diversity

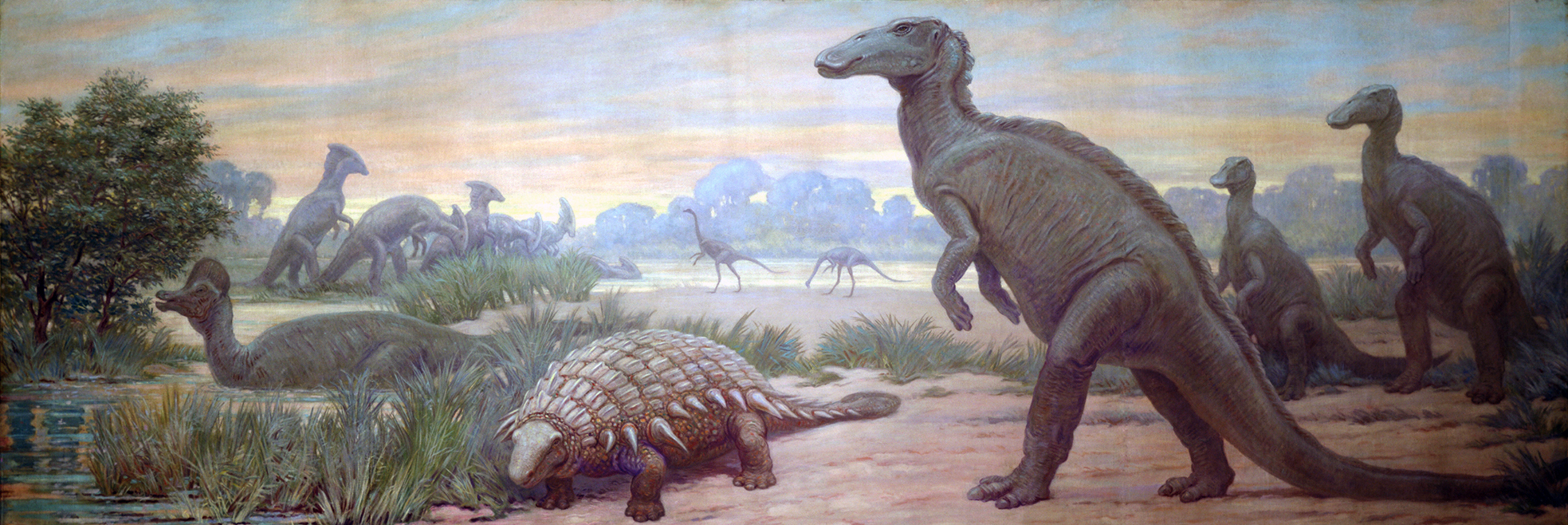

The late Cretaceous period was experiencing what scientists now call the “last dinosaur renaissance.” Never before had so many different species of dinosaurs coexisted on our planet. From the massive Triceratops herds thundering across the plains to the fearsome Tyrannosaurus rex stalking through primeval forests, diversity was at its absolute peak.

Recent fossil discoveries have revealed that new dinosaur species were still evolving right up until the asteroid impact. The famous Hell Creek Formation in Montana shows us a snapshot of this incredible variety, with over 40 different dinosaur species living in the same region. Think of it like a prehistoric version of the Amazon rainforest, but instead of colorful birds and monkeys, massive reptiles filled every ecological niche imaginable.

What’s even more fascinating is that many of these dinosaurs were becoming more intelligent and socially complex. Evidence suggests that some species were developing advanced pack hunting strategies and even primitive communication systems that might have eventually led to something resembling language.

Massive Herbivore Migrations That Shaped Continents

The sheer scale of dinosaur migrations in the late Cretaceous was something our modern world has never seen. Imagine herds of Edmontosaurus stretching from horizon to horizon, their movements carving permanent pathways across continents. These weren’t just random wanderings—they were organized, seasonal migrations that involved millions of individuals.

These massive herbivores were essentially living landscaping crews, shaping entire ecosystems with their feeding habits. A single herd of Triceratops could strip an area of vegetation so thoroughly that it would take decades to recover. But this wasn’t destructive—it was creative. Their movements spread seeds across vast distances and created the diverse plant communities that supported even more species.

The migration routes these dinosaurs followed were becoming increasingly sophisticated. Some species had developed internal navigation systems that rivaled modern sea turtles, following magnetic fields and seasonal cues across thousands of miles. These ancient highways would have connected distant ecosystems in ways we’re only beginning to understand.

The Rise of Intelligent Predators

Tyrannosaurs weren’t just mindless killing machines—they were becoming increasingly intelligent problem-solvers. Recent studies of T. rex brain structures suggest they possessed cognitive abilities comparable to modern crocodiles and birds, with some species showing evidence of complex social behaviors and even tool use.

The late Cretaceous saw the emergence of pack-hunting strategies among various theropod dinosaurs. Dromaeosaurids like Velociraptor were coordinating attacks with a level of sophistication that would have made them formidable opponents for any prey. They weren’t just following instinct—they were adapting their hunting techniques based on experience and environmental changes.

Perhaps most intriguingly, some predatory dinosaurs were developing what paleontologists call “teaching behaviors.” Adult raptors appeared to be showing juveniles how to hunt, much like modern wolves or lions. This knowledge transfer between generations suggests that dinosaur intelligence was on a trajectory that could have led to truly remarkable cognitive development.

Flying Giants Ruling the Skies

The pterosaurs of the late Cretaceous were reaching sizes that defy imagination. Quetzalcoatlus, with its 35-foot wingspan, was essentially a flying giraffe—a creature so large that it challenged our understanding of what’s physically possible in a flying animal. These weren’t just oversized birds; they were engineered for efficiency in ways that modern aircraft designers study with envy.

These aerial giants weren’t alone in the skies. A diverse community of pterosaurs filled every flying niche, from tiny fish-catchers to massive scavengers that could soar for days without landing. The air above the late Cretaceous world was as busy as any modern airport, with flight paths that spanned continents.

What makes this even more remarkable is that these pterosaurs were developing increasingly sophisticated flight control systems. Some species showed evidence of dynamic soaring techniques that allowed them to harvest energy from wind patterns, potentially enabling them to fly across entire oceans without stopping.

Marine Reptiles Creating Underwater Civilizations

While dinosaurs dominated the land, marine reptiles were building complex underwater societies that would have put any modern marine ecosystem to shame. Mosasaurs, the sea serpents of the Cretaceous, were growing to lengths that rivaled modern sperm whales, but with intelligence levels that may have exceeded most marine mammals.

The underwater world of 66 million years ago was experiencing its own evolutionary explosion. Plesiosaurs had developed echolocation abilities that allowed them to hunt in the deepest ocean trenches, while sea turtles the size of small cars migrated across ancient oceans following currents that no longer exist.

Perhaps most fascinating were the emerging social structures among marine reptiles. Some mosasaur species showed evidence of cooperative hunting and even primitive cultural behaviors passed down through generations. The oceans were becoming laboratories for intelligence evolution that parallel what was happening on land.

Plant Evolution Racing to Keep Up

The plant kingdom was undergoing its own revolution in the late Cretaceous, driven by the constant pressure from massive herbivorous dinosaurs. Flowering plants were exploding in diversity, developing new defense mechanisms and reproductive strategies at a pace that would have made Charles Darwin dizzy with excitement.

Some plants were literally growing armor to protect themselves from dinosaur feeding. Thick-barked trees and plants with chemical defenses were becoming increasingly common, creating a botanical arms race that was driving innovation on both sides. It was like watching nature’s own version of military research and development.

The relationship between dinosaurs and plants was becoming increasingly sophisticated. Some species were developing mutualistic relationships where dinosaurs would disperse seeds in exchange for nutritious fruits, creating the first versions of what we now see in modern rainforests. These partnerships were setting the stage for ecosystem complexity that we’re still discovering today.

Climate Engineering on a Planetary Scale

The dinosaurs of the late Cretaceous weren’t just living in their environment—they were actively reshaping it. The massive herds were creating weather patterns through their sheer biomass, generating heat and moisture that influenced regional climates across entire continents.

Consider the scale: a single herd of sauropods could contain enough biomass to match a small city’s worth of humans. When these herds moved, they didn’t just change the landscape—they changed the atmosphere above them. Their breathing, body heat, and metabolic processes were creating microclimates that supported entirely different plant and animal communities.

The dinosaurs were also becoming increasingly important in global carbon cycling. Their massive appetites were processing plant material at rates that influenced atmospheric CO2 levels, while their waste products were fertilizing vast areas and supporting rapid plant growth. They were essentially functioning as a biological climate control system.

The Development of Proto-Technologies

Some dinosaur species were beginning to show behaviors that scientists are now recognizing as the earliest forms of tool use and technology. Certain theropods were using stones to crack tough shells, while others were manipulating their environment in ways that suggest problem-solving abilities we typically associate with much later evolution.

The most intriguing evidence comes from nesting sites where dinosaurs appeared to be using environmental engineering to control temperature and humidity. Some species were building sophisticated nests that functioned like primitive greenhouses, using decomposing vegetation to generate heat and moisture for their eggs.

Perhaps most remarkably, some dinosaurs were showing evidence of what paleontologists cautiously call “proto-agriculture.” Certain herbivorous species appeared to be selectively grazing in patterns that encouraged the growth of their preferred plants, essentially practicing a primitive form of farming that wouldn’t be seen again until human civilization emerged.

Social Complexity Reaching New Heights

The social structures of late Cretaceous dinosaurs were becoming increasingly complex, with some species developing hierarchies and cooperative behaviors that rivaled modern mammals. Hadrosaurs, the duck-billed dinosaurs, were creating communities that included specialized roles for different individuals within the herd.

Evidence suggests that some dinosaur species were developing primitive forms of culture, with behaviors and knowledge being passed down through generations rather than being purely instinctual. Young dinosaurs were learning from their elders in ways that created regional variations in behavior—essentially dinosaur dialects and traditions.

The communication systems these dinosaurs were developing were becoming increasingly sophisticated. Some species were using complex combinations of vocalizations, body language, and even chemical signals to coordinate group activities across vast distances. These communication networks were connecting dinosaur communities across entire continents.

Evolutionary Arms Race Reaching Critical Mass

The late Cretaceous was witnessing an evolutionary arms race that was accelerating at an unprecedented pace. Predators were becoming larger, faster, and more intelligent, while prey species were developing increasingly sophisticated defensive strategies and escape mechanisms.

This wasn’t just about size—it was about innovation. Some dinosaurs were developing sensory abilities that would have seemed like superpowers to earlier species. Enhanced vision, hearing, and even electromagnetic sensitivity were giving certain dinosaurs advantages that were reshaping predator-prey relationships across the globe.

The pace of evolution was so rapid that new species were emerging within relatively short geological timeframes. This evolutionary pressure cooker was creating biological innovations that might have led to capabilities we can barely imagine if given more time to develop.

The Emergence of Dinosaur Civilizations

Perhaps the most speculative but intriguing possibility is that some dinosaur species were on the verge of developing what we might recognize as early civilizations. The combination of intelligence, social complexity, and environmental manipulation suggests that certain species were approaching thresholds that could have led to technological development.

The evidence is subtle but compelling: organized construction projects, long-distance communication networks, and collaborative problem-solving on scales that required planning and coordination beyond simple instinct. Some paleontologists argue that we’re seeing the earliest stages of what might have eventually become dinosaur cities.

If the asteroid had missed, these proto-civilizations might have had millions of years to develop technologies and social structures that would have made our planet unrecognizable. The thought of dinosaur architects, engineers, and philosophers isn’t just science fiction—it’s a logical extension of the evolutionary trajectories we can observe in the fossil record.

A World That Might Have Been

The late Cretaceous world was teetering on the edge of transformations that would have redefined what it means to be alive on Earth. The dinosaurs weren’t just surviving—they were innovating, collaborating, and evolving in directions that might have led to a completely different kind of planetary intelligence.

Without the asteroid’s intervention, we might have inherited a world where massive reptilian civilizations coexisted with flying cities populated by pterosaurs, where marine reptiles had developed underwater technologies, and where the very concept of evolution had been accelerated beyond our current understanding.

The tragedy of the extinction event isn’t just that the dinosaurs died—it’s that we lost the chance to see what they might have become. Their final moments represent not just an ending, but the termination of evolutionary possibilities that will never be explored again.

The Legacy of What Could Have Been

Today, as we watch birds at our feeders and visit museums filled with dinosaur skeletons, we’re looking at the remnants of a world that was on the verge of something extraordinary. The late Cretaceous wasn’t just the end of an era—it was the interruption of a story that was just beginning to get interesting.

The dinosaurs of 66 million years ago were writing the first chapters of what might have been the most remarkable evolutionary story our planet has ever seen. Their intelligence, their social complexity, and their environmental impact were all pointing toward a future that would have been as alien to us as it would have been magnificent.

Understanding what we lost when the asteroid struck isn’t just about paleontology—it’s about recognizing the incredible potential that evolution can produce when given time and opportunity. The dinosaurs remind us that intelligence and civilization aren’t human monopolies, but natural phenomena that can emerge from any lineage given the right conditions and enough time.

The next time you see a bird building a nest or watch a documentary about dinosaurs, remember that you’re looking at the descendants and relatives of creatures who were on the verge of rewriting the rules of life itself. What would you have expected from a world where T. rex had another 10 million years to evolve?