Picture this: a massive Tyrannosaurus rex thundering across the prehistoric landscape, its bone-crushing jaws wide open, pursuing a herd of duck-billed Edmontosaurus. But what you might not realize is that this isn’t just a simple chase scene from millions of years ago. It’s actually the culmination of an evolutionary arms race that lasted tens of millions of years, where every adaptation by prey animals triggered a counter-adaptation by predators, and vice versa.

The Mesozoic Era wasn’t just about giant dinosaurs randomly stomping around. It was a period of intense evolutionary pressure where survival depended on constantly outsmarting, outrunning, or outfighting your opponents. This biological warfare shaped some of the most incredible creatures our planet has ever seen.

The Foundation of Evolutionary Warfare

The concept of an evolutionary arms race is surprisingly simple yet profoundly impactful. When prey animals develop better defenses, predators must evolve more effective hunting strategies to survive. This creates a continuous cycle of adaptation and counter-adaptation that can span millions of years.

During the Mesozoic Era, this process reached extraordinary heights. The sheer diversity of dinosaur species reflects this intense evolutionary pressure. Every ecological niche became a battleground where life-or-death adaptations determined which species would thrive and which would vanish forever.

Think of it like a never-ending game of rock-paper-scissors, except the stakes are survival itself. Each “move” in this game took thousands of generations to develop, but the results were spectacular creatures that seem almost too incredible to have actually existed.

Early Predator Innovations

The earliest theropod dinosaurs were relatively small, quick hunters that relied on speed and agility rather than brute force. These Triassic predators like Coelophysis developed lightweight bones, powerful leg muscles, and sharp teeth perfectly suited for catching small prey.

Their hunting strategies were remarkably sophisticated for such ancient creatures. Pack hunting behavior likely evolved early, allowing these predators to take down prey much larger than themselves. Fossil evidence suggests coordinated attacks and even possible ambush tactics.

But perhaps most importantly, these early predators established the basic body plan that would later evolve into some of the most fearsome hunters in Earth’s history. Their bipedal stance, powerful hindlimbs, and specialized killing claws became the foundation for millions of years of predatory evolution.

The Rise of Armored Herbivores

As predators became more dangerous, herbivorous dinosaurs responded with increasingly elaborate defensive strategies. The ankylosaurs represent one of the most extreme examples of this evolutionary response. These walking tanks developed thick, bony armor plating that could deflect even the most powerful predator attacks.

Ankylosaurus itself was essentially a living fortress. Its back was covered in rows of bony plates and spikes, while its skull was so heavily armored that it looked more like a medieval helmet than a dinosaur head. The famous tail club could deliver devastating blows capable of breaking the bones of attacking predators.

These defensive adaptations weren’t just about passive protection. Many armored dinosaurs developed active defensive behaviors, positioning themselves strategically and using their armor as weapons. The evolutionary investment in defense was so significant that some ankylosaurs devoted nearly half their body weight to armor and defensive structures.

Speed vs. Stealth: The Raptor Revolution

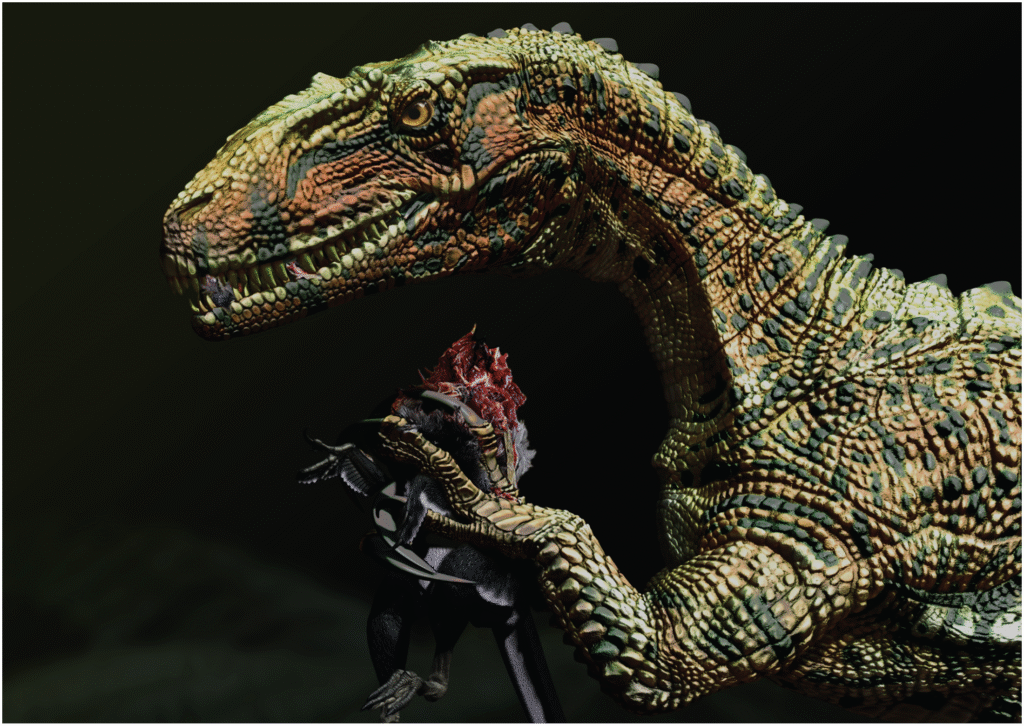

While some predators evolved towards massive size and overwhelming power, others took a completely different approach. The dromaeosaurids, commonly known as raptors, represent one of the most successful predatory innovations in dinosaur history. These creatures combined intelligence, speed, and lethal precision into a nearly perfect killing machine.

Velociraptor and its relatives developed enlarged brain cases, suggesting advanced problem-solving abilities and complex social behaviors. Their famous sickle-shaped claws weren’t just for slashing – they were precision instruments designed to grip and control struggling prey while delivering fatal wounds.

The raptor hunting strategy was fundamentally different from the brute-force approach of larger predators. They likely hunted in coordinated packs, using teamwork and intelligence to overcome prey that might be individually stronger or better defended. This represented a major escalation in the evolutionary arms race.

The Herbivore Response: Size and Numbers

Faced with increasingly sophisticated predators, many herbivorous dinosaurs responded by growing larger and developing complex social structures. The sauropods represent the ultimate expression of the “safety in size” strategy, with some species reaching lengths of over 100 feet and weights exceeding 70 tons.

These massive herbivores created entirely new ecological dynamics. Their sheer size made them nearly invulnerable to most predators once they reached adulthood. Even the largest theropods would think twice before attacking a fully grown Argentinosaurus or Patagotitan.

But size came with its own challenges. Sauropods had to develop specialized feeding strategies, complex digestive systems, and unique reproductive methods to support their massive bodies. The evolutionary investment in gigantism was enormous, but it provided an effective defense against predation.

Horns, Frills, and Charging Tactics

The ceratopsians developed perhaps the most visually striking defensive adaptations of any dinosaur group. Triceratops and its relatives combined massive skull shields with formidable horns, creating a defensive system that was both intimidating and highly effective against predators.

These elaborate head displays served multiple purposes beyond simple defense. The colorful frills likely played important roles in species recognition and social communication. The positioning and size of horns varied dramatically between species, suggesting intense evolutionary pressure to develop unique defensive strategies.

Recent research suggests that ceratopsians were far more aggressive than previously thought. Rather than simply defending themselves when attacked, they may have actively charged predators, using their horns as offensive weapons. This represents a significant escalation in the arms race between predators and prey.

The Tyrannosaur Supremacy

No discussion of the Mesozoic arms race would be complete without examining the ultimate expression of predatory evolution: the tyrannosaurs. These massive predators developed bone-crushing bite forces that could deliver over 12,000 pounds of pressure per square inch, making them capable of piercing even the thickest armor.

Tyrannosaurus rex wasn’t just big – it was perfectly engineered for killing large, heavily defended prey. Its massive skull housed powerful jaw muscles, while its teeth were designed to grip and tear through flesh and bone. The famous tiny arms may have been used for grappling with struggling prey.

The tyrannosaur success story represents millions of years of evolutionary refinement. From their smaller ancestors, they evolved increasingly powerful builds, more sophisticated hunting strategies, and the ability to take down virtually any prey animal in their environment. They became the apex predators of their time.

Defensive Herding and Social Complexity

As predators became more dangerous, many herbivorous dinosaurs developed complex social behaviors for protection. Evidence suggests that duck-billed dinosaurs like Maiasaura lived in vast herds that could number in the thousands, creating a formidable defensive network.

These social structures weren’t just about safety in numbers. Herding dinosaurs likely developed sophisticated communication systems, including various calls and visual signals to coordinate group movements and warn of approaching dangers. Some species may have even posted sentries while others fed.

The evolution of complex social behaviors represents a major advancement in the arms race. By working together, relatively defenseless individual dinosaurs could create collective defensive capabilities that rivaled the most heavily armored species. This social evolution changed the entire dynamic of predator-prey relationships.

Camouflage and Deception Strategies

Not all evolutionary adaptations involved massive size or fearsome weapons. Many dinosaurs developed sophisticated camouflage and deception strategies that allowed them to avoid predation through stealth rather than confrontation. Recent discoveries have revealed that many dinosaurs had complex coloration patterns.

Sinosauropteryx, one of the first dinosaurs found with preserved coloration, had a reddish-brown color with darker stripes that would have provided excellent camouflage in forest environments. This represents a completely different approach to the arms race – avoiding detection entirely rather than surviving attacks.

Some predators also used camouflage to their advantage, developing coloration patterns that allowed them to ambush unsuspecting prey. The evolution of visual deception created an entirely new dimension to the predator-prey relationship, where success often depended on remaining unseen rather than winning direct confrontations.

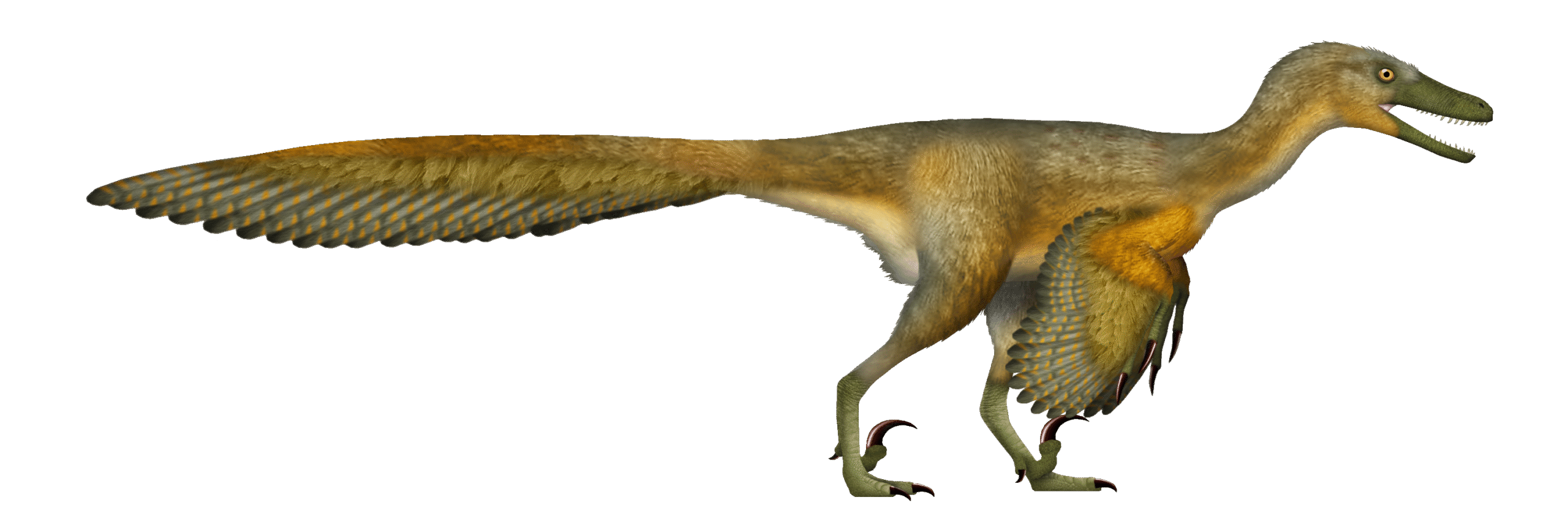

The Flying Escape Route

Perhaps the most dramatic response to ground-based predation pressure was the evolution of flight. While true powered flight remained rare among dinosaurs, many species developed gliding abilities that allowed them to escape terrestrial predators by taking to the air.

Microraptor and similar species had four wings and could glide between trees, effectively removing themselves from the ground-based arms race entirely. This aerial escape strategy opened up completely new ecological niches and feeding opportunities while providing unparalleled protection from most predators.

The evolution of flight represents one of the most successful escape strategies in the entire arms race. By conquering the air, some dinosaur lineages freed themselves from millions of years of evolutionary pressure, allowing them to diversify into the incredible variety of birds we see today.

Aquatic Sanctuaries

Another escape strategy involved returning to aquatic environments where different rules applied. While not true dinosaurs, marine reptiles like plesiosaurs and ichthyosaurs represented parallel evolutionary solutions to predation pressure, developing in oceanic environments where different hunting and defensive strategies were required.

Some dinosaurs also adapted to semi-aquatic lifestyles. Spinosaurus, with its paddle-like tail and fish-eating adaptations, represents a fascinating example of how the arms race drove some predators to explore entirely new hunting grounds and prey species.

The movement into aquatic environments created separate evolutionary arms races with their own unique dynamics. Aquatic predators developed different hunting strategies, while aquatic prey evolved their own specialized defensive adaptations, creating parallel evolutionary battles in marine ecosystems.

The End Game: Extinction and Legacy

The Mesozoic arms race came to an abrupt end 66 million years ago when an asteroid impact triggered a mass extinction event. This catastrophic event eliminated non-avian dinosaurs and reset the evolutionary playing field completely, ending one of the most spectacular periods of evolutionary innovation in Earth’s history.

However, the legacy of this arms race lives on in modern ecosystems. The basic principles of predator-prey evolution continue to shape life on Earth, from the relationship between wolves and elk to the ongoing battle between disease organisms and immune systems.

The extinction event didn’t end evolutionary arms races – it simply created new opportunities for different groups of animals to engage in similar evolutionary battles. Mammals, birds, and other survivors of the extinction began their own arms races that continue today.

Modern Echoes of Ancient Battles

The evolutionary principles that drove the Mesozoic arms race continue to shape modern ecosystems in fascinating ways. Contemporary predator-prey relationships follow remarkably similar patterns to those seen in dinosaur communities, suggesting that these evolutionary dynamics represent fundamental aspects of life itself.

Cheetahs and gazelles engage in their own version of the speed arms race, while porcupines and their predators continue the ancient battle between offensive weapons and defensive armor. Even human technology and warfare follow similar patterns of action and reaction that mirror the evolutionary strategies of dinosaurs.

Understanding these ancient arms races provides valuable insights into how modern ecosystems function and how they might respond to environmental changes. The lessons learned from 165 million years of dinosaur evolution remain relevant to conservation efforts and ecosystem management today.

The Never-Ending Story

The Jurassic arms race represents one of the most spectacular examples of evolutionary innovation in Earth’s history. Over millions of years, predators and prey pushed each other to develop increasingly sophisticated adaptations, creating some of the most incredible creatures our planet has ever seen. From the massive armor of ankylosaurs to the bone-crushing power of tyrannosaurs, every adaptation tells a story of survival, innovation, and the relentless drive of evolution.

This ancient battle between hunters and hunted shaped not just the dinosaurs themselves, but the entire structure of Mesozoic ecosystems. The strategies developed during this period – from social cooperation to technological innovation – continue to influence how life adapts and survives in modern environments.

The next time you see a bird outside your window, remember that you’re looking at a living descendant of this incredible evolutionary arms race. What new adaptations do you think the future might hold?