In the prehistoric world that existed millions of years ago, dinosaurs reigned supreme across Earth’s landscapes. These magnificent creatures didn’t just peacefully coexist – they engaged in epic struggles for territory, resources, and survival. Fossil evidence has revealed fascinating insights into how these prehistoric giants fought each other, from specialized combat adaptations to complex battle strategies. The violent confrontations between these ancient reptiles helped shape their evolution and defined the ecological relationships of the Mesozoic Era. Let’s explore the fascinating world of dinosaur combat and the evidence that allows paleontologists to reconstruct these dramatic prehistoric encounters.

The Weaponry of Theropod Dinosaurs

Theropod dinosaurs, including the famous Tyrannosaurus rex, evolved some of the most formidable natural weapons ever seen in terrestrial animals. Their primary weapons were their massive jaws, filled with serrated teeth that could deliver devastating bite forces. T. rex, for example, could exert a bite force estimated at 12,800 pounds, powerful enough to crush bone and tear through flesh with ease. These predators also employed their powerful necks to drive these bites home, creating wounds that would cause massive trauma and blood loss in their opponents. Some theropods also used their clawed forelimbs, though they varied significantly in strength and utility across different species, with some, like Carnotaur, having extremely reduced arms that played little role in combat.

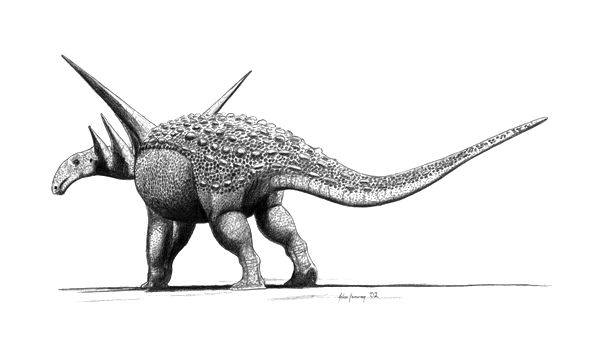

Armored Defenses of the Ankylosaurs

Ankylosaurs represent nature’s answer to the tank – heavily armored dinosaurs built for defense with offensive capabilities. These quadrupedal herbivores were covered in bony plates called osteoderms that formed a protective shield against predator attacks. The most impressive weapon in the ankylosaur arsenal was the tail club, a massive bony knob at the end of a stiffened tail that could be swung with tremendous force. Studies of Ankylosaurus tail clubs suggest they could generate enough force to break bones, potentially shattering the legs of an attacking predator or rival ankylosaur. This combination of armor and active defense made ankylosaurs formidable opponents despite their plant-eating lifestyle, allowing them to survive in environments dominated by fearsome predators.

The Horn and Frill Combat of Ceratopsians

Ceratopsians like Triceratops were equipped with some of the most obvious combat adaptations among dinosaurs. Their iconic facial horns served as formidable weapons for both defense against predators and combat with rivals. The prominent frill extending from the back of their skulls served multiple purposes, including protection for the neck region during combat. Fossil evidence reveals that many ceratopsian specimens bear damage marks consistent with horn impacts, suggesting these dinosaurs engaged in head-to-head combat similar to modern rams or bison. These confrontations likely occurred during mating seasons when males competed for dominance and access to females. The diverse array of horn configurations across different ceratopsian species suggests these structures evolved through sexual selection pressures, with more impressive horns providing advantages in these ritual combats.

Thagomizer: The Deadly Tail Spikes of Stegosaurs

Stegosaurs employed one of the dinosaur world’s most distinctive weapons – the thagomizer. This arrangement of long, sharp spikes on the end of their tails could be swung with precision against approaching threats. Fossil evidence confirms the deadly effectiveness of this weapon, including an Allosaurus vertebra with a puncture wound that perfectly matches a Stegosaurus tail spike. The tail itself was remarkably flexible, allowing the stegosaur to swing its spikes in a wide arc to keep predators at bay. This weapon was complemented by the distinctive plates along the stegosaur’s back, which may have made the dinosaur appear larger and more intimidating during confrontations. The thagomizer represents a specialized adaptation that allowed these herbivores to defend themselves against much larger and more aggressive carnivores.

Pack Hunting Tactics Among Predatory Dinosaurs

Evidence suggests some predatory dinosaurs adopted pack-hunting strategies to take down larger prey, fundamentally changing the dynamics of prehistoric combat. Dromaeosaurs like Velociraptor and Deinonychus have been found in fossil assemblages that hint at group behavior, potentially indicating coordinated hunting methods. Their specialized “killing claws” on each foot could deliver deep slashing wounds and, when employed by multiple individuals attacking from different angles, could quickly bring down much larger prey. More controversially, some paleontologists have suggested larger theropods like Allosaurus may have hunted in loose packs, based on multiple specimens found at single kill sites. This social hunting behavior would have given predators a significant advantage against even the most well-defended herbivores, as no single defensive adaptation could protect against multiple attackers striking simultaneously.

The Biomechanics of Sauropod Defense

Despite their enormous size, sauropods like Brachiosaurus and Diplodocus faced predation threats from large theropods. These long-necked giants relied primarily on their massive size as their first line of defense, as few predators would risk attacking a healthy adult. When forced to fight, sauropods could employ their massive tails as whips, generating supersonic cracks and delivering devastating blows to attackers. Biomechanical studies suggest the tips of some sauropod tails could move at speeds exceeding 30 meters per second, creating enough force to seriously injure or deter predators. Some species also possessed specialized defensive features, such as the sharp spines running along the necks of dicraeosaurids or the unusual club-like tail of Shunosaurus. Young sauropods, more vulnerable to predation, likely remained close to adults for protection, benefiting from the herd’s collective defense capabilities.

Evidence of Combat in the Fossil Record

Paleontologists have uncovered compelling evidence of dinosaur combat preserved in the fossil record. Tyrannosaurus specimens show bite marks matching the teeth of other tyrannosaurs, suggesting violent confrontations between rivals. A famous fossil pair of Velociraptor and Protoceratops preserved in Mongolia shows the two locked in mortal combat, with the Velociraptor’s killing claw embedded in the ceratopsian’s neck while the herbivore’s beak grips the predator’s arm. Triceratops skulls frequently show healed injuries consistent with horn impacts from other Triceratops, providing direct evidence of intraspecific combat. Pathological bone growths, healed fractures, and bite marks on various dinosaur fossils all paint a picture of a world where violent confrontations were commonplace. These fossilized injuries give paleontologists valuable insights into how these ancient creatures fought and what weapons they employed most frequently.

Sexual Dimorphism and Combat for Mating Rights

Many dinosaur species likely engaged in combat primarily for reproductive opportunities rather than predation. Evidence of sexual dimorphism – physical differences between males and females – suggests combat played a crucial role in mating competition. The elaborate frills and horns of ceratopsians like Styracosaurus may have evolved to be larger and more ornate in males for displaying dominance and fighting rivals. Similar patterns are seen in the elaborate crests of hadrosaurs and the sail-backed structures of spinosaurs. This parallels behaviors seen in modern animals like deer, where males possess antlers primarily used for combat with other males rather than predator defense. These mating-related fights likely followed ritualized patterns that minimized fatal injuries while still establishing dominance hierarchies within populations, though escalation to serious injury remained possible when evenly matched rivals competed.

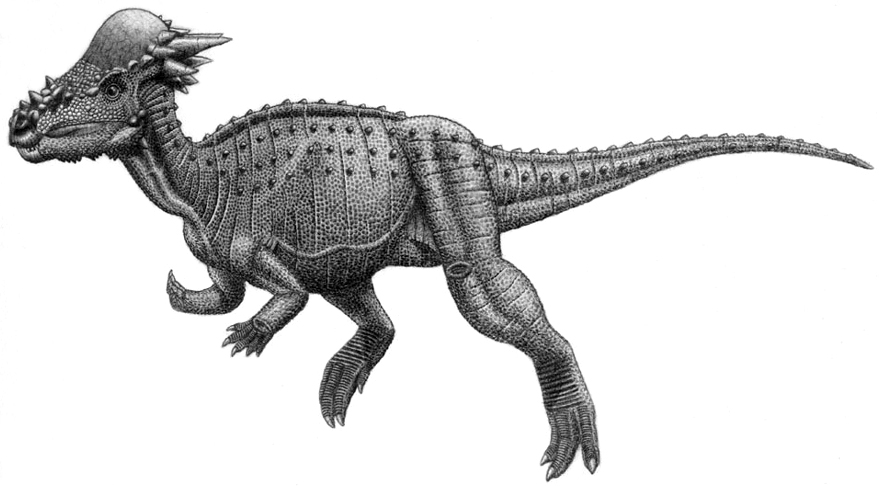

Specialized Hunting Adaptations of Dromaeosaurs

Dromaeosaurs like Velociraptor and Deinonychus possessed some of the most specialized hunting adaptations among all dinosaurs. Their signature weapon was the enlarged “killing claw” on the second toe of each foot – a sickle-shaped talon that could be held off the ground while running and deployed during attacks. Biomechanical studies suggest these claws were used to restrain struggling prey while the predator’s jaws delivered killing bites, rather than slashing, as often depicted in popular media. These agile hunters also possessed unusually flexible wrists that allowed them to grasp prey with their three-fingered hands, providing additional control during combat. Their lightweight skulls featured jaws lined with recurved teeth ideal for slicing through flesh but less suited for crushing bone like their larger theropod relatives. These specialized adaptations made dromaeosaurs formidable predators despite their relatively small size compared to other theropods.

Defensive Herding Behaviors

Many herbivorous dinosaurs adopted herding as a primary defensive strategy against predators, fundamentally changing the dynamics of dinosaur combat. Fossil trackways and bonebeds provide evidence that hadrosaurs, ceratopsians, and sauropods often lived and traveled in groups. These herds offered multiple advantages during predator encounters, including more vigilant eyes to spot danger, confusion effects that made it difficult for predators to isolate individuals, and collective defense where multiple adults could confront a threat. Young and vulnerable individuals could be protected in the center of the herd, surrounded by larger adults. Some herding species may have formed defensive circles when threatened, with adults facing outward with their most dangerous weapons – be they horns, tail clubs, or simply their size – presented toward approaching predators. This social behavior dramatically increased survival chances against even the most formidable carnivores.

The Evolutionary Arms Race

Dinosaur combat capabilities evolved through a continuous arms race between predators and prey over millions of years. As predators developed more powerful jaws and claws, prey species responded with better defenses like thicker armor, longer horns, and more potent active weapons. This evolutionary pressure drove the development of increasingly specialized adaptations on both sides of the predator-prey relationship. The thickened skull domes of pachycephalosaurs likely evolved in response to the need for better protection during combat. Similarly, the massive size increase seen in some sauropods may represent an evolutionary response to predation pressure from ever-larger theropods. This dynamic relationship shaped dinosaur evolution throughout the Mesozoic, producing the incredible diversity of combat adaptations observed in the fossil record and driving the development of increasingly sophisticated fighting techniques.

Modern Insights from Extant Archosaurs

Studies of modern archosaurs – birds and crocodilians – provide valuable insights into how their dinosaur relatives might have fought. Crocodilian combat involves powerful bite-and-twist techniques and full-body wrestling that leave distinctive injury patterns, helping paleontologists interpret similar marks on dinosaur fossils. Large birds like cassowaries employ powerful kicks with sharp claws in a manner potentially similar to some theropod dinosaurs. Territorial displays among modern reptiles and birds, featuring ritualized posturing before physical combat, suggest similar behaviors may have been common among dinosaurs. Even the air sac respiratory system of birds, inherited from their dinosaur ancestors, provides clues about stamina and fighting capability, as this efficient breathing system would have allowed sustained activity during prolonged combat. By studying these living relatives, researchers can better reconstruct the combat behaviors of extinct dinosaurs beyond what fossils alone can tell us.

Remarkable Dinosaur Battle Adaptations

Beyond the well-known weapons like horns and teeth, dinosaurs evolved numerous specialized adaptations specifically for combat. The osteoderm-covered tails of some sauropods like Shunosaurus and Saltasaurus functioned as heavy clubs for defense. The unusual “thumb spikes” of Iguanodon could be used as daggers in close combat, providing these otherwise peaceful herbivores with a last-ditch defensive weapon. Some theropods like Carnotaurus developed thickened skull bones that could withstand high-impact head-butting contests similar to modern rams. Pachycephalosaurs took this adaptation to the extreme with dome-shaped skulls surrounded by small horns, creating biological battering rams specifically evolved for head-to-head combat. The diversity of these specialized combat adaptations highlights how central fighting was to dinosaur ecology and evolution, shaping their bodies in response to the constant pressure of survival in a world where combat skill often determined which individuals would survive to reproduce.

Conclusion

The combat adaptations and fighting behaviors of dinosaurs represent one of the most fascinating aspects of prehistoric life. From the devastating bite of Tyrannosaurus to the tail clubs of ankylosaurs, these ancient creatures evolved an impressive array of weapons and defenses that shaped their interactions and drove their evolution. The fossil record preserves tantalizing glimpses of these ancient battles – bite marks, broken bones, and even opponents preserved in the act of combat. By combining this evidence with studies of modern animals and biomechanical analysis, paleontologists continue to reconstruct the dramatic confrontations that characterized life in the Mesozoic. These prehistoric battles weren’t just spectacular events; they were fundamental forces that shaped dinosaur evolution, driving the development of increasingly specialized adaptations and complex behaviors throughout their 165-million-year reign.