Picture walking through a lush Mesozoic forest, where thunderous footsteps shake the ground and mysterious calls echo through ancient trees. The world of dinosaurs wasn’t silent. In fact, their auditory landscape was far richer than we ever imagined. Recent scientific breakthroughs have pulled back the curtain on one of paleontology’s most intriguing mysteries: what could these magnificent creatures actually hear?

You might think that understanding dinosaur hearing is impossible since their soft ear tissues vanished millions of years ago. Yet modern technology has revealed remarkable secrets hidden inside fossilized skulls. Through cutting-edge CT scans and meticulous analysis, scientists are reconstructing the ancient soundscape that shaped dinosaur behavior, communication, and survival. Let’s dive into this fascinating world where silence is broken by prehistoric discovery.

The Hidden Architecture of Dinosaur Ears

Dinosaurs had internal auditory systems, not external ear flaps (pinnae) like many modern mammals. Their hearing anatomy included an inner ear with a cochlea, a single middle ear bone (stapes), and an inferred tympanic membrane. This internal design was surprisingly sophisticated despite lacking visible ears.

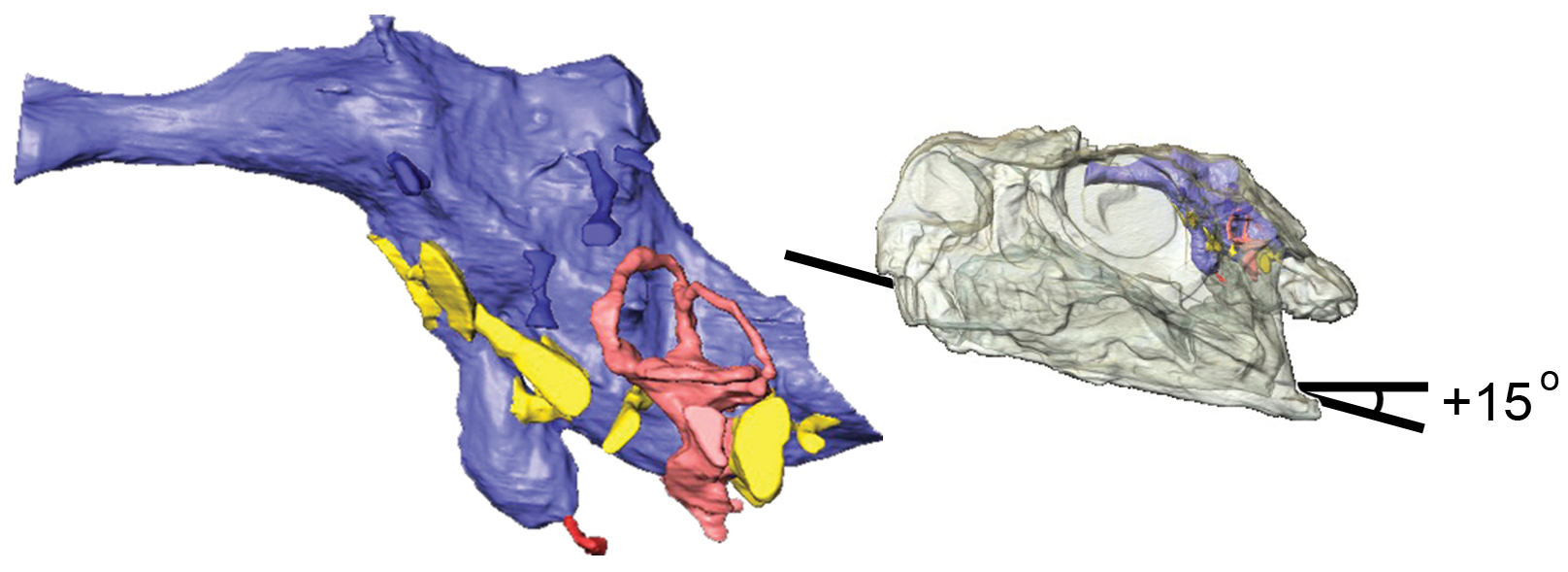

While the soft tissues of dinosaur ears are not preserved in the fossil record, paleontologists can infer their auditory capabilities by studying the bony structures of their skulls, particularly the inner ear region. Analysis of fossilized braincases and endocasts (casts of the brain cavity) reveals the presence of an inner ear labyrinth, including semicircular canals (for balance) and a cochlea (or cochlear duct), which is responsible for detecting sound vibrations.

In many modern reptiles and birds, this membrane is located either flush with the surface of the skull, sometimes covered by scales or feathers, or slightly recessed within a small cavity. It does not protrude as an external flap. The absence of external ears didn’t mean dinosaurs were deaf – quite the opposite.

Revolutionary CT Scanning Technology

CT scan and other non-destructive imaging techniques have greatly facilitated the development of vertebrate paleontology not only in revealing hidden structures but also providing 3D models for teaching and exhibition. This breakthrough has transformed how we study ancient life.

Using high-resolution x-ray microtomography (micro-CT) they can look into both the exteriors and interiors of fossils at a microscopic scale, in three dimensions. Best of all, the technique does not require slicing up the samples, so the same fossils can be examined again and again. CT scanning enables researchers to create detailed three-dimensional models of the spaces inside fossil skulls where ear structures once existed. These scans reveal the size and shape of inner ear canals, the position of the middle ear, and the pathways for nerves related to hearing.

Synchrotron scanning is CT taken to the max, the superhero of visualisation. Materials that are hard to differentiate using conventional CT can be more readily discerned thanks to the intensity of synchrotron X-rays, which are better able to pass through materials and produce results faster.

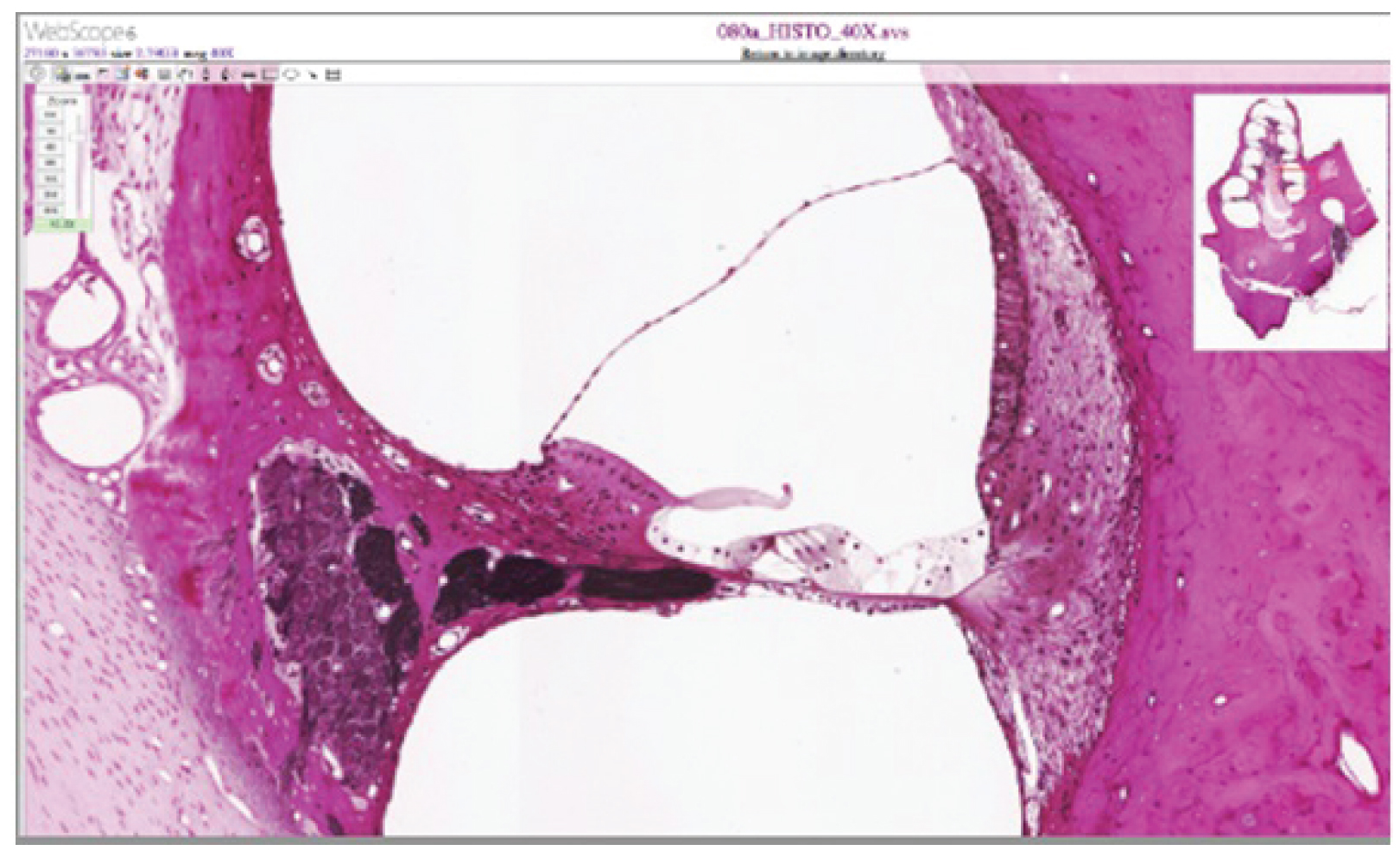

The Cochlea – Nature’s Sound Analyzer

The length and coiling of the cochlea can provide clues about the range of frequencies an animal could hear. This tiny structure holds enormous secrets about dinosaur hearing capabilities.

All vertebrates have a tube-like canal called the cochlea deep in their inner ear. Studies of living mammals and birds show that the longer this canal, the wider the range of frequencies an animal can hear and the better they can hear very faint sounds. The researchers found that ancestors and early relatives of dinosaurs evolved a longer region of the inner ear called the cochlea, which is associated with hearing high-frequency sounds.

This is because the cochlea, a bone in the inner ear, was remarkably long. In animals alive today, this is usually associated with the ability to hear low-frequency sounds very well. The evolution of cochlear length reveals surprising adaptations across different dinosaur species.

Frequency Range and Sound Detection

Dinosaur auditory systems were well-adapted for sound transmission and likely capable of hearing a range of frequencies, including low-frequency sounds. Studies on dinosaur inner ear structures suggest they were likely capable of hearing a range of frequencies similar to modern birds and crocodiles, which often includes a significant range of low-frequency sounds.

Probably a lot of low frequency sounds, like the heavy footsteps of another dinosaur, if University of Maryland professor Robert Dooling and his colleagues are right. “The best guess is that dinosaurs were probably somewhat similar to some of the very large mammals of today, such as the elephants, but with poorer high frequency hearing than most mammals of today,” says Dooling.

As a general rule, animals can hear the sounds they produce. Dinosaurs probably also could hear very well the footsteps of other dinosaurs. Elephants, for instance, are purported to be able to hear, over great distances, the very low frequency infrasound generated by the footsteps of other elephants. Low-frequency sounds travel further and can penetrate obstacles, which would be advantageous for large animals in diverse environments.

Parental Communication and High-Pitched Calls

The researchers found that ancestors and early relatives of dinosaurs evolved a longer region of the inner ear called the cochlea, which is associated with hearing high-frequency sounds. The most likely reason, the paleontologists propose, is that this adaptation allowed adult animals to hear the squeaks and chirps of their hatchlings, similar to the attentive parenting of modern-day alligators and crocodiles.

Bhullar said the data suggest that the cochlear shape’s transformation in ancestral reptiles coincided with the development of high-pitched location, danger, and hatching calls in juveniles. The study suggests that the transformation of cochlear shape in ancestral reptiles coincided with the development of high-pitched calls in juvenile dinosaurs. It is believed that adult dinosaurs used their enhanced hearing abilities for communication and parental care.

“The singing birds of today therefore may trace their vocal abilities to the squeaks that tiny, scaly reptiles made as they hatched over 200 million years ago. “We gently suggest that modern bird song, in all its mellifluous glory, is a retention in adults of juvenile high-pitched chirps,” Bhullar says.

Specialized Night Hunters

Our scans showed that S. deserti had an extremely elongated inner ear canal for its size – also similar to that of the living barn owl and proportionally much longer than all of the other 88 living bird species we analyzed for comparison. This discovery revealed extraordinary auditory adaptations in certain dinosaur species.

But our work also shows that S. deserti also had incredibly sensitive hearing similar to modern-day owls. This is the first time these two traits have been found in the same fossil, suggesting that this small, desert-dwelling dinosaur that lived in ancient Mongolia was probably a specialized night-hunter of insects and small mammals.

Shuvuuia had long inner ear canals, broadening the range of the dinosaur’s hearing. Schmitz and colleagues propose this dinosaur had excellent hearing, comparable to the auditory ability of modern barn owls. Such precise hearing, combined with Shuvuuia’s large eyes, suggest this dinosaur was active at night. Based on our measurements, among dinosaurs, we found that predators had generally better hearing than herbivores.

Comparing Giants: T. Rex and Other Massive Predators

At Chicago’s Field Museum is a preserved T. Rex fossil named Sue. Sue had a stapes or an inner ear bone. The inclusion of the stapes indicates that T. Rex could hear sound vibrations and then send those to its eardrum to make out noises. This massive predator possessed sophisticated hearing apparatus.

No one knows for sure how good T. rex’s hearing was, but scientists believe that it was quite hypersensitive. So it’s possible that T. rex had excellent hearing. This would have come in handy for hunting, as they could have easily heard their prey from a distance.

Hearing played a crucial role in the survival and social interactions of dinosaurs, just as it does for most vertebrates today. Predator and Prey Detection: Auditory cues would have been vital for both predators to locate prey and for prey animals to detect approaching threats. The rustling of leaves, the snap of a twig, or the distant thud of footsteps could signal danger or opportunity. Communication: Many dinosaurs are thought to have communicated through vocalizations, such as bellows, roars, or chirps, which would have required a functional auditory system to perceive.

Flight and Balance Through Inner Ear Analysis

According to the study, the shape of the inner ear offers reliable signs as to whether an animal soared gracefully through the air, flew only fitfully, walked on the ground, or sometimes went swimming. In some cases, the inner ear even indicates whether a species did its parenting by listening to the high-pitched cries of its babies.

Several clusters were the result of the structure of the top portion of the inner ear, called the vestibular system. This, said Bhullar, is “the three-dimensional structure that tells you about the maneuverability of the animal. The form of the vestibular system is a window into understanding bodies in motion.” · One vestibular cluster corresponded with “sophisticated” fliers, species with a high level of aerial maneuverability.

Most significantly, the inner ears of birdlike dinosaurs called troodontids, pterosaurs, Hesperornis, and the “dino-bird” Archaeopteryx fall within this cluster. A fascinating aspect of the study on the ear structures of dinosaurs is the identification of inner ear clusters that are associated with specific flying abilities. Through analyzing the shape and structure of the vestibular system, researchers have gained insights into the maneuverability of different species.

The ancient world of dinosaurs was far from silent. Through the lens of modern CT scanning technology, we’ve discovered that these magnificent creatures possessed sophisticated hearing systems that rival many modern animals. From the thunderous footsteps of massive predators to the delicate chirps of hatchlings, dinosaurs lived in a rich auditory landscape that guided their hunting, communication, and parenting behaviors.

“Of all the structures that one can reconstruct from fossils, the inner ear is perhaps that which is most similar to a mechanical device,” said Yale paleontologist Bhart-Anjan Bhullar, senior author of the new study, published in the journal Science. This mechanical precision has allowed scientists to peer into the sensory world of creatures that vanished millions of years ago.

The discoveries about dinosaur hearing continue to reshape our understanding of these ancient giants. They weren’t just massive, terrifying beasts or gentle plant-eaters – they were complex animals with sophisticated sensory systems that allowed them to thrive for over 160 million years. What do you think about these incredible revelations? Tell us in the comments.