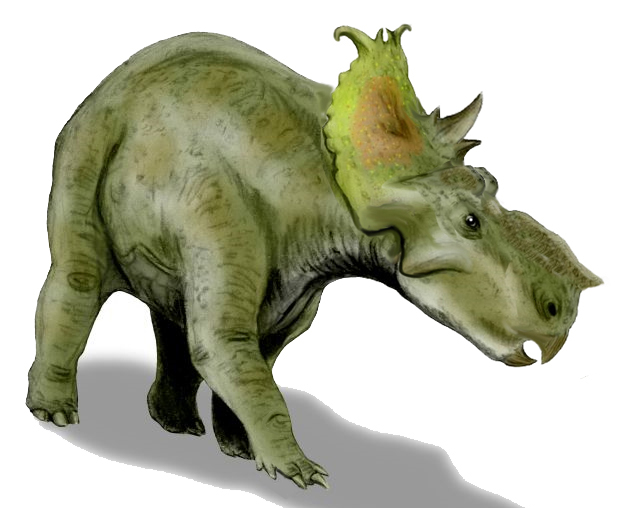

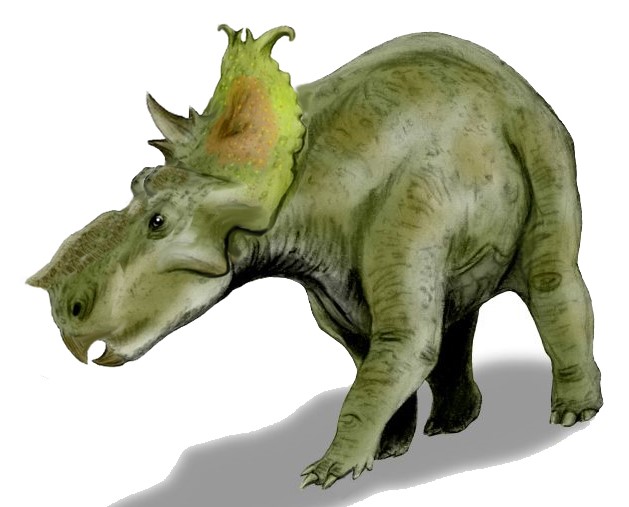

Pachyrhinosaurus, meaning “thick-nosed lizard,” stands as one of the most distinctive members of the ceratopsian dinosaur family. Unlike its more famous cousin, the Triceratops, this herbivorous dinosaur lacked the prominent facial horns that characterized many ceratopsians. Instead, Pachyrhinosaurus sported a massive, bony pad on its nose called a nasal boss, creating a unique profile that has fascinated paleontologists since its discovery. This Late Cretaceous dinosaur, which roamed what is now North America between 73.5 and 66 million years ago, offers a fascinating glimpse into the diversity of horned dinosaurs and the evolutionary adaptations that allowed different species to thrive in similar ecological niches.

Discovery and Naming History

The first Pachyrhinosaurus specimens were discovered in Alberta, Canada, in 1946 by Charles M. Sternberg, who found a partial skull in the Horseshoe Canyon Formation. Sternberg formally described and named the genus in 1950, with the name derived from Greek words “pachys” (thick), “rhino” (nose), and “sauros” (lizard), directly referencing the dinosaur’s most distinctive feature. Since this initial discovery, several other species have been identified and named, including P. canadensis (the type species), P. lakustai, and P. perotorum. The most significant discoveries came decades after Sternberg’s initial find, with rich bone beds uncovered in Alberta and Alaska yielding hundreds of specimens that transformed our understanding of this unusual dinosaur. These mass accumulations of remains have allowed paleontologists to study growth patterns and population dynamics in ways impossible with isolated specimens.

Physical Characteristics and Size

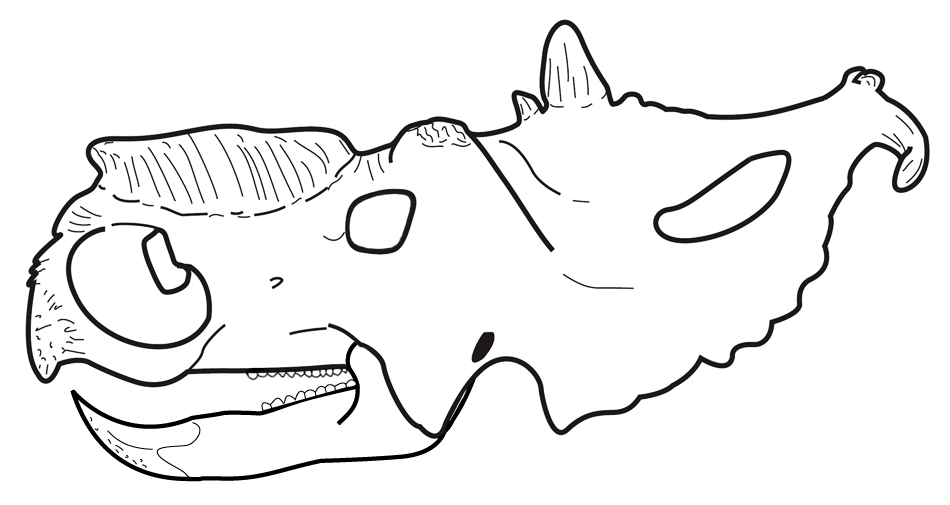

Pachyrhinosaurus was a substantial quadrupedal herbivore, measuring approximately 18 to 26 feet (5.5 to 8 meters) in length and standing about 7 feet (2.1 meters) tall at the hip. Weight estimates place adults between 3 and 4 tons, making them formidable inhabitants of their Late Cretaceous environments. Like other ceratopsians, they possessed a large, bony frill extending from the back of the skull, though the frill of Pachyrhinosaurus was relatively modest compared to some relatives. Their bodies were robust and rhinoceros-like, with strong limbs supporting their considerable bulk. The most distinctive feature, of course, was the massive, roughened bony pad (the nasal boss) that dominated the face, replacing the nose horn seen in many other ceratopsians. Some species also had additional bumps or bosses over the eyes, creating an even more unusual appearance.

The Distinctive Nasal Boss

The nasal boss that gives Pachyrhinosaurus its name represents one of the most unusual cranial structures among all dinosaurs. Unlike the sharp horns of Triceratops, this structure formed a massive, rough-textured pad of bone that covered much of the snout. In some specimens, this boss measures more than 20 centimeters thick and shows a highly rugose (rough and wrinkled) surface texture. The boss likely formed through the fusion and overgrowth of elements that, in other ceratopsians, would have developed into a nose horn. Paleontologists have identified distinct variations in the nasal boss between different Pachyrhinosaurus species—P. canadensis featured a more rounded boss, while P. Lakustai displayed a more complex structure with multiple bumps and protuberances. This diversity suggests the boss served important species-recognition functions, similar to the distinctive horn patterns in modern bovids.

Species Diversity Within the Genus

The Pachyrhinosaurus genus currently includes three validated species, each separated by time and geography. Pachyrhinosaurus canadensis, the type species, lived in what is now southern Alberta approximately 71.5-70.0 million years ago. Pachyrhinosaurus lakustai, named after Alberta fossil collector Al Lakusta, who discovered an enormous bone bed in 1972, inhabited northern Alberta about 73.5-72.5 million years ago and exhibits more complex cranial ornamentation than P. canadensis. The most recently described species, Pachyrhinosaurus perotorum, named in honor of Texas businessman and presidential candidate Ross Perot, lived in Alaska around 70-69 million years ago and featured the largest body size among the known species. Each species shows subtle but important differences in their cranial bosses, frill structure, and overall proportions. These differences developed as populations became isolated from one another and adapted to slightly different environmental conditions across the vast territory they inhabited.

Habitat and Geographic Distribution

Pachyrhinosaurus inhabited the western regions of North America during the Late Cretaceous period, with fossils primarily found in Alberta, Canada, and northern Alaska. During this time, these regions experienced a much warmer climate than today, with the western interior of North America featuring a large inland sea that divided the continent. Pachyrhinosaurus lived in the western coastal plain environments bordering this seaway, areas characterized by river systems, floodplains, and forests. The Alaskan populations of P. perotorum are particularly interesting to paleontologists, as they demonstrate that these dinosaurs could thrive in high-latitude environments that experienced prolonged periods of darkness during winter months. The geographic range of Pachyrhinosaurus suggests considerable adaptability to different environmental conditions, from the relatively warmer southern habitats to the more challenging northern realm, where seasonal changes in daylight would have affected plant growth and food availability.

Diet and Feeding Adaptations

As a ceratopsian dinosaur, Pachyrhinosaurus was an obligate herbivore equipped with specialized structures for processing tough plant material. Their dental batteries consisted of columns of teeth that continually grew and replaced throughout the animal’s life, providing constant sharp cutting surfaces for vegetation. Each tooth column functioned as a single cutting unit, with dozens of teeth forming a continuous shearing surface. The powerful beak-like structure at the front of the mouth, formed by the rostral and predentary bones, allowed Pachyrhinosaurus to crop vegetation effectively before processing it with the cheek teeth. Based on the height of the jaw joint relative to the tooth row, paleontologists believe Pachyrhinosaurus employed a slicing motion rather than grinding when chewing. The diet likely consisted primarily of the tough, fibrous vegetation that dominated Late Cretaceous landscapes, including cycads, ferns, and primitive flowering plants that were becoming increasingly common during this period.

Social Behavior and Herding Evidence

The discovery of extensive bone beds containing multiple Pachyrhinosaurus individuals of various ages provides compelling evidence that these dinosaurs lived in herds or groups for at least part of their lives. The Pipestone Creek bone bed in Alberta, which yielded remains of at least 14 individuals of P. lakustai, and the Liscomb bone bed in Alaska with hundreds of P. perotorum specimens, suggest catastrophic events that killed entire groups simultaneously. Age distribution analysis of these bone beds indicates mixed-age groups containing both juveniles and adults, a pattern consistent with family groups or herds seen in many modern herbivores. Living in groups would have provided several advantages, including protection from predators like tyrannosaurids and improved ability to locate quality feeding grounds. The presence of elaborate display structures like the nasal boss and frill further supports the idea that social interactions and recognition were important aspects of Pachyrhinosaurus behavior, potentially playing roles in dominance hierarchies or mate selection within these gregarious dinosaurs.

Growth and Development

Studies of Pachyrhinosaurus specimens at different growth stages have revealed fascinating insights into their development from juvenile to adult. Young Pachyrhinosaurus had markedly different cranial ornaments than adults, with small, horn-like structures that only later developed into the characteristic boss as the animal matured. This ontogenetic transformation represents one of the most dramatic growth-related changes known among ceratopsians. Bone histology studies indicate that Pachyrhinosaurus, like many other dinosaurs, experienced rapid growth during early life stages, followed by slower growth as the animal approached skeletal maturity. Analysis of growth rings in fossil bones suggests that individuals reached adult size in approximately 10-15 years. Interestingly, the development of the distinctive nasal boss appears to have coincided with sexual maturity, suggesting this feature may have played important roles in mate attraction or competition, similar to the horns and antlers of modern mammals that often develop fully only upon reaching reproductive age.

Defensive Strategies and Predator Interactions

Despite its lack of prominent horns, Pachyrhinosaurus was well-equipped to defend itself against the formidable predators of the Late Cretaceous, including tyrannosaurids like Albertosaurus and Gorgosaurus. The massive nasal boss may have functioned as a battering ram during confrontations with predators, allowing the animal to deliver powerful, blunt-force blows. The bony frill, while not as large as in some other ceratopsians, provided crucial protection for the neck region and attachment sites for powerful muscles. Their substantial body size alone would have deterred many predators, with adults likely too large for all but the most determined tyrannosaurids to attack. Some Pachyrhinosaurus fossils show evidence of healed injuries consistent with predator attacks, demonstrating that they sometimes survived such encounters. The herding behavior exhibited by these dinosaurs would have further enhanced their defensive capabilities, with multiple adults potentially coordinating to protect vulnerable juveniles—a strategy employed by many modern herbivores when confronting dangerous predators.

Potential Function of the Nasal Boss

The distinctive nasal boss of Pachyrhinosaurus has inspired numerous hypotheses regarding its function beyond simple species recognition. Some paleontologists suggest the boss served as a weapon for intraspecific combat, with males potentially engaging in head-pushing contests similar to those seen in modern musk oxen or bighorn sheep. The rough, thickened surface of the boss would have been ideal for absorbing the impact of such collisions without causing serious injury to the combatants. Other researchers propose the boss may have supported a keratinous (horn-like) covering that enhanced its visual appearance, potentially with bright coloration for display purposes. Vascularization patterns within the bone suggest good blood supply, which could support either combat or display functions. Another intriguing possibility is that the boss served multiple roles simultaneously—functioning in species recognition, sexual selection displays, and occasional defensive or combative situations as needed, reflecting the complexity of structures that evolve under multiple selective pressures.

Pachyrhinosaurus in the Ceratopsian Family Tree

Pachyrhinosaurus belongs to the centrosaurine subfamily of ceratopsids, a group characterized by their relatively simple frills and elaborate nasal ornamentation. Phylogenetic analyses place Pachyrhinosaurus in close relationship with other centrosaurines like Achelousaurus and Einiosaurus, with whom it shares certain cranial features. These three genera form what paleontologists call a transitional morphological series, showing an evolutionary progression from dinosaurs with conventional nasal horns toward the extreme boss development seen in Pachyrhinosaurus. This relationship provides valuable insights into evolutionary patterns within ceratopsians, demonstrating how dramatic morphological innovations could arise through relatively modest changes to developmental pathways. The centrosaurine line diverged from the chasmosaurines (which include Triceratops) approximately 80-79 million years ago, with both subfamilies exploring different approaches to cranial ornamentation while maintaining the same basic body plan. Pachyrhinosaurus represents one of the most derived centrosaurines, displaying the culmination of evolutionary trends toward elaborate facial structures that began earlier in the group’s history.

Paleoecology and Contemporary Fauna

Pachyrhinosaurus shared its Late Cretaceous ecosystems with a diverse assemblage of dinosaurs and other animals, creating complex ecological communities. In the Alberta environments where P. canadensis and P. lakustai lived, they coexisted with hadrosaurs like Edmontosaurus and Hypacrosaurus, armored ankylosaurs such as Edmontonia and Euoplocephalus, and predators including Albertosaurus and Daspletosaurus. The Alaskan environments inhabited by P. perotorum featured similarly diverse fauna, though adapted to more northern conditions. These ecosystems were dominated by conifers, ginkgoes, and early flowering plants, with rich understory vegetation providing food for the numerous herbivores. Rivers and wetlands supported aquatic species, including fish, turtles, and crocodilians, while small mammals, birds, and amphibians rounded out the ecological communities. Pachyrhinosaurus likely occupied a middle to high browser niche in these ecosystems, using its powerful beak to crop vegetation at various heights while avoiding direct competition with low-browsing ankylosaurs and the more specialized hadrosaurs that could process different plant materials.

Extinction and Legacy

Pachyrhinosaurus survived until close to the end of the Cretaceous period, with the most recent specimens dating to approximately 68-66 million years ago, just before the catastrophic mass extinction event that eliminated all non-avian dinosaurs. This asteroid-induced extinction, which occurred 66 million years ago, brought an end to not just Pachyrhinosaurus but all ceratopsians and most other large terrestrial animals. The legacy of Pachyrhinosaurus lives on through scientific study and popular culture, with its distinctive appearance making it a favorite subject for paleontological illustrations and museum exhibits. The remarkable bone beds discovered in Alberta and Alaska continue to yield new information about these animals, their growth patterns, population structures, and evolutionary relationships. Perhaps most importantly, Pachyrhinosaurus exemplifies how evolution can produce unexpected morphological solutions—trading the seemingly advantageous sharp horns of related ceratopsians for a completely different structure that served its bearers well for millions of years before their lineage’s ultimate extinction.

Cultural Impact and Representations

While not as universally recognized as Triceratops or Tyrannosaurus, Pachyrhinosaurus has made notable appearances in popular culture that have helped bring this unusual dinosaur to public attention. The most prominent representation came in the 2013 film “Walking With Dinosaurs 3D,” where a Pachyrhinosaurus named Patchi served as the main character, introducing audiences worldwide to this lesser-known ceratopsian. Several major natural history museums feature Pachyrhinosaurus reconstructions, including the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Alberta and the Museum of the North in Alaska, where visitors can appreciate the distinctive appearance of this dinosaur. Detailed scientific models and illustrations have evolved significantly over decades as new fossil discoveries have refined our understanding of their appearance. The striking bone beds containing multiple individuals have also captured the public imagination, telling stories of catastrophic events that preserved entire herds for future discovery. As one of the more distinctive ceratopsians with its unusual nasal boss, Pachyrhinosaurus continues to serve as an excellent educational example of the diversity and evolutionary experimentation that characterized dinosaur evolution.

Conclusion

Pachyrhinosaurus represents one of the most fascinating examples of evolutionary innovation among dinosaurs. With its massive nasal boss replacing the typical ceratopsian horns, this herbivore followed a distinctive evolutionary pathway that proved successful for millions of years. From its discovery in Alberta to the rich bone beds that have yielded hundreds of specimens, Pachyrhinosaurus continues to provide paleontologists with valuable insights into dinosaur growth, behavior, and adaptation. As we piece together the story of these thick-nosed dinosaurs, we gain a deeper appreciation for the remarkable diversity of ceratopsian dinosaurs and their important role in the Late Cretaceous ecosystems of North America. Though they vanished in the mass extinction event 66 million years ago, their fossils continue to speak volumes about the incredible adaptability and success of dinosaurian life.