You might think of dinosaurs as those massive, gray-skinned beasts from movies, but recent scientific discoveries paint a far more colorful and sophisticated picture. The incredible revelation that dinosaurs used complex camouflage systems has revolutionized our understanding of prehistoric life. Far from being simple, lumbering creatures, these ancient animals developed intricate survival strategies that rival anything we see in modern wildlife.

These groundbreaking discoveries prove that dinosaurs faced intense predation pressure, even the heavily armored ones. The evidence shows us a dynamic prehistoric world where survival depended not just on size or weapons, but on the ability to disappear in plain sight.

The Revolutionary Discovery of Psittacosaurus Camouflage

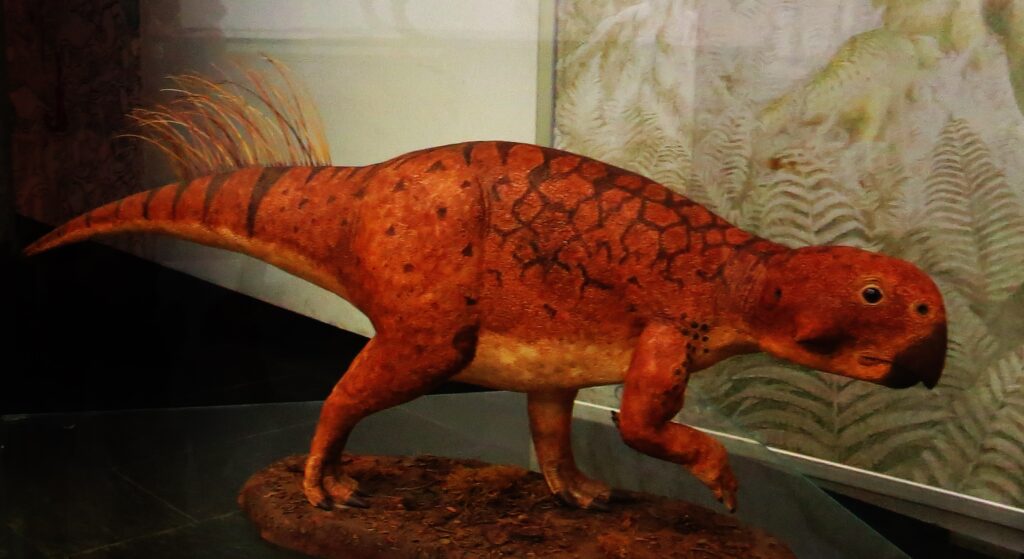

The dinosaur Psittacosaurus is the first dinosaur to show evidence of countershading, a type of camouflage in which animals have darker-colored backs and lighter bellies. This remarkable specimen from China lived approximately 120 million years ago and was about the size of a golden retriever.

Analysis of the exquisitely preserved fossil remains has revealed one of the most elaborate dinosaur paint jobs ever seen, including a brown back and a lighter belly. What makes this discovery so extraordinary is that researchers could see actual pigmentation patterns preserved in the fossil itself. When he first saw an exceptionally well-preserved specimen of Psittacosaurus in Germany in 2009, which included multiple areas of dark pigment, Vinther says his reaction was: “Holy cow, this thing has beautiful color patterns.”

Understanding Countershading in Ancient Reptiles

Countershading camouflage uses a dark-to-light gradient from back to belly to counter the light-to-dark gradient created by illumination. The body appears flatter and less conspicuous. This technique works by canceling out the shadows that would normally reveal a three-dimensional shape to predators.

Psittacosaurus used a basic tactic called countershading, in which the top of an animal’s body is dark and its belly or underside is lighter. This same pattern appears throughout the modern animal kingdom, from sharks to deer. The principle remains surprisingly consistent across millions of years of evolution.

That type of coloring, called countershading, shows up in animals from penguins to fish and may act as a form of camouflage. It lightens parts of the body typically in shadow, and darkens parts typically exposed to light. “If you want to hide, it makes sense to try and obliterate those shadows,” Rowland says.

Sophisticated Testing Methods Reveal Habitat Preferences

Scientists didn’t just guess about how this camouflage worked. To learn more about the dinosaur’s environs, the researchers built a life-size model of the Psittacosaurus and painted it a dull gray, providing a neutral background for assessing shadows on the body. At a nearby botanic garden, the model was photographed on both clear and cloudy days, out in the open and under cover of vegetation. The images show that the Psittacosaurus’s coloring provided the best camouflage in diffuse light, not full sun. So the reptile probably lived in the forest rather than on the savanna, the researchers conclude.

The reconstructed patterns closely matched the “optimal countershading” for the diffuse light under a forest canopy, the team reports online today in Current Biology. That corresponds well with evidence from previous paleobotanical studies of the region, which suggest that it was dotted with lakes surrounded by coniferous forests. This scientific approach transformed paleontology by showing how color patterns could reveal ancient environments.

Feathered Dinosaurs and Their Bandit Masks

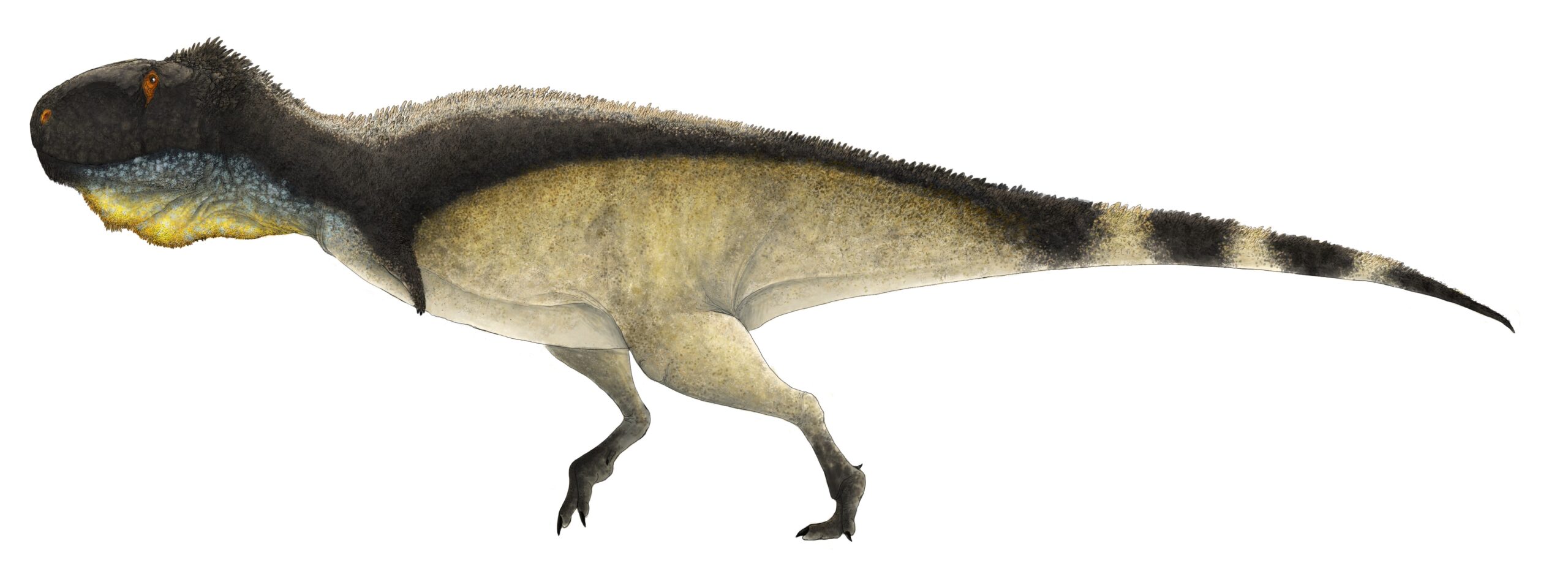

Researchers from the University of Bristol have revealed how a small feathered dinosaur used its colour patterning, including a bandit mask-like stripe across its eyes, to avoid being detected by its predators and prey. By reconstructing the likely colour patterning of the Chinese dinosaur Sinosauropteryx, researchers have shown that it had multiple types of camouflage which likely helped it to avoid being eaten in a world full of larger meat-eating dinosaurs.

Their findings reveal that Sinosauropteryx was countershaded – dark on top and light underneath. It also sported a ‘bandit’ mask on its face, resembling that of a raccoon. This striking pattern served multiple purposes, helping the small predator both avoid larger threats and sneak up on its own prey.

The patterns include a dark stripe around the eye, or ‘bandit mask’, which in modern birds helps to hide the eye from would-be predators, and a striped tail that may have been used to confuse both predators and prey. These elaborate patterns show just how sophisticated dinosaur camouflage systems had become.

The Science Behind Fossilized Colors

The biological key to solving the coloration puzzle comes down to miniscule structures called melanosomes. These are tiny, blobby organelles that contain pigment, or melanin, and are present in soft tissues such as skin, scales, and feathers. These microscopic structures can millions of years under the right conditions.

The color patterns visible in the fossil are derived from preserved melanin on the specimen evident as melanosome-shaped structures under the electron microscope. Scientists use powerful electron microscopes to identify these ancient pigment structures, distinguishing them from bacteria that might have colonized the decaying remains.

Different shapes and arrangements of melanosomes in bird feathers are associated with different colours, including black, brown, red, buff and even iridescent structural colours. Our discovery of melanosomes in a fossil feather therefore opens up the possibility of predicting feather colour in ancient birds and perhaps in other theropod dinosaurs.

Armored Giants Still Needed to Hide

Even the most heavily armored dinosaurs relied on camouflage for survival. Here we describe a new, exquisitely three-dimensionally preserved nodosaurid ankylosaur, Borealopelta markmitchelli… We identify melanin in the organic residues through mass spectroscopic analyses and observe lighter pigmentation of the large parascapular spines, consistent with display, and a pattern of countershading across the body. With an estimated body mass exceeding 1,300 kg, B. markmitchelli was much larger than modern terrestrial mammals that either are countershaded or experience significant predation pressure as adults.

Presence of countershading suggests predation pressure strong enough to select for concealment in this megaherbivore despite possession of massive dorsal and lateral armor, illustrating a significant dichotomy between Mesozoic predator-prey dynamics and those of modern terrestrial systems. This discovery fundamentally changed how we think about dinosaur ecosystems.

Ancient Arms Race Between Predators and Prey

“These color patterns are a testament to an arms race [between predator and prey] that took place 120 million years ago,” Vinther says. The development of sophisticated camouflage systems reveals the intense evolutionary pressure between hunters and the hunted during the Mesozoic era.

Today large “attack-proof” animals like elephants and rhinos do not use camouflaging, he says. Scientists have always assumed that massive dinosaurs would be equally shielded from predators. But the newly discovered fossil suggests that millions of years ago bulky dinosaurs like Borealopelta might have been preyed on by even larger dinosaurs, Henderson says. Those could have included the sharp-toothed, long-clawed Acrocanthosaurus, which grew as long as 11-12 meters.

Modern predator-prey dynamics may not be directly applicable to those of the Mesozoic due to the dominance of very large, visually oriented theropod dinosaurs. The sheer size and visual acuity of predatory dinosaurs created pressures unlike anything in today’s world.

Complex Visual Systems Drove Camouflage Evolution

Similarly to modern birds, dinosaurs in the early Cretaceous period, when Sinosauropteryx lived, probably had tetrachromatic vision, meaning that they could see four colors. This might have given them a significant advantage over today’s mammalian predators, which tend to have poorer vision. “Predators back then had excellent vision, and to camouflage yourself against such a predator, you had to have really good camouflage,” says Vinther.

“They had excellent vision, were fierce predators and would have evolved camouflage patterns like we see in living mammals and birds.” This advanced visual system created an evolutionary pressure cooker where only the most effectively camouflaged animals could .

Multiple Camouflage Strategies in Single Species

By reconstructing the likely colour patterning of the Chinese dinosaur Sinosauropteryx, researchers have shown that it had multiple types of camouflage which likely helped it to avoid being eaten in a world full of larger meat-eating dinosaurs, including relatives of the infamous Tyrannosaurus Rex, as well as potentially allowing it to sneak up more easily on its own prey.

These weren’t simple, single-purpose patterns. Researchers were also curious about what purpose the Sinosauropteryx’s bandit mask and striped tail might have served. In living species, multiple functions for bandit masks have been proposed, such as reducing glare – something that may have been useful to a species such as Sinosauropteryx, whose fossils were deposited in lakeside environments.

Revolutionary Impact on Paleontology

Fossil color studies really do offer an unprecedented opportunity to make interpretations about behavior and biology from the fossil record. This breakthrough opened entirely new avenues of research that were previously considered impossible.

“By reconstructing the colour of these long-extinct dinosaurs, we have gained a better understanding of not only how they behaved and possible predator-prey dynamics, but also the environments in which they lived. This highlights how palaeocolour reconstructions can tell us things not possible from looking at just the bones of these animals.” Scientists can now read fossils like never before, extracting behavioral and ecological information from color patterns.

Feather color in dinosaurs, for example, may reveal whether color patterns were useful for camouflage or peacock-like courtship displays, and if there were color differences between the sexes, as in many modern birds. The possibilities for future discoveries seem endless.

Conclusion: A Colorful Prehistoric World

The discovery of dinosaur camouflage has transformed our understanding of these ancient creatures from simple, gray monsters into sophisticated animals with complex survival strategies. Far from all being the lumbering prehistoric grey beasts of past children’s books, at least some dinosaurs showed sophisticated colour patterns to hide from and confuse predators, just like today’s animals.

These findings reveal that the Mesozoic world was a dynamic, colorful place where survival depended on evolutionary ingenuity. From the forest-dwelling Psittacosaurus to the armored Borealopelta, dinosaurs developed camouflage systems that helped them navigate a world filled with visual predators unlike anything alive today.

What fascinates you most about these ancient survival strategies? The idea that even tank-like armored dinosaurs needed to hide challenges everything we thought we knew about prehistoric life.