Picture this: your neighbor’s pet bird lays an egg, and roughly two to three weeks later, a fluffy little chick pokes its beak through the shell. Now imagine if that same egg sat there for six months instead. That’s precisely what happened in the Mesozoic Era when dinosaurs ruled the earth.

For decades, scientists assumed dinosaur eggs would much like modern bird eggs, given that birds are direct descendants of dinosaurs. Yet recent groundbreaking research has completely revolutionized our understanding of prehistoric reproduction. By examining the tiniest details in fossilized embryonic teeth, researchers have uncovered one of paleontology’s most surprising secrets about how long it truly took for baby dinosaurs to emerge from their shells.

A Revolutionary Discovery in Embryonic Teeth

The breakthrough came through an unlikely source: microscopic growth lines in dinosaur embryo teeth. These daily growth rings, called von Ebner lines, form as teeth develop, much like tree rings, allowing scientists to literally count the days an embryo spent developing inside its egg. This technique had never been applied to dinosaur embryos before, though it was successfully used to study tooth development in modern crocodiles and mammals.

Scientists were surprised nobody had attempted this approach previously, given the wealth of information these microscopic structures could provide. The method requires incredibly well-preserved specimens, which are among the rarest fossils on Earth. While fossilized dinosaur eggs are extremely common, fossilized dinosaur embryos are extraordinarily rare.

The Species That Changed Everything

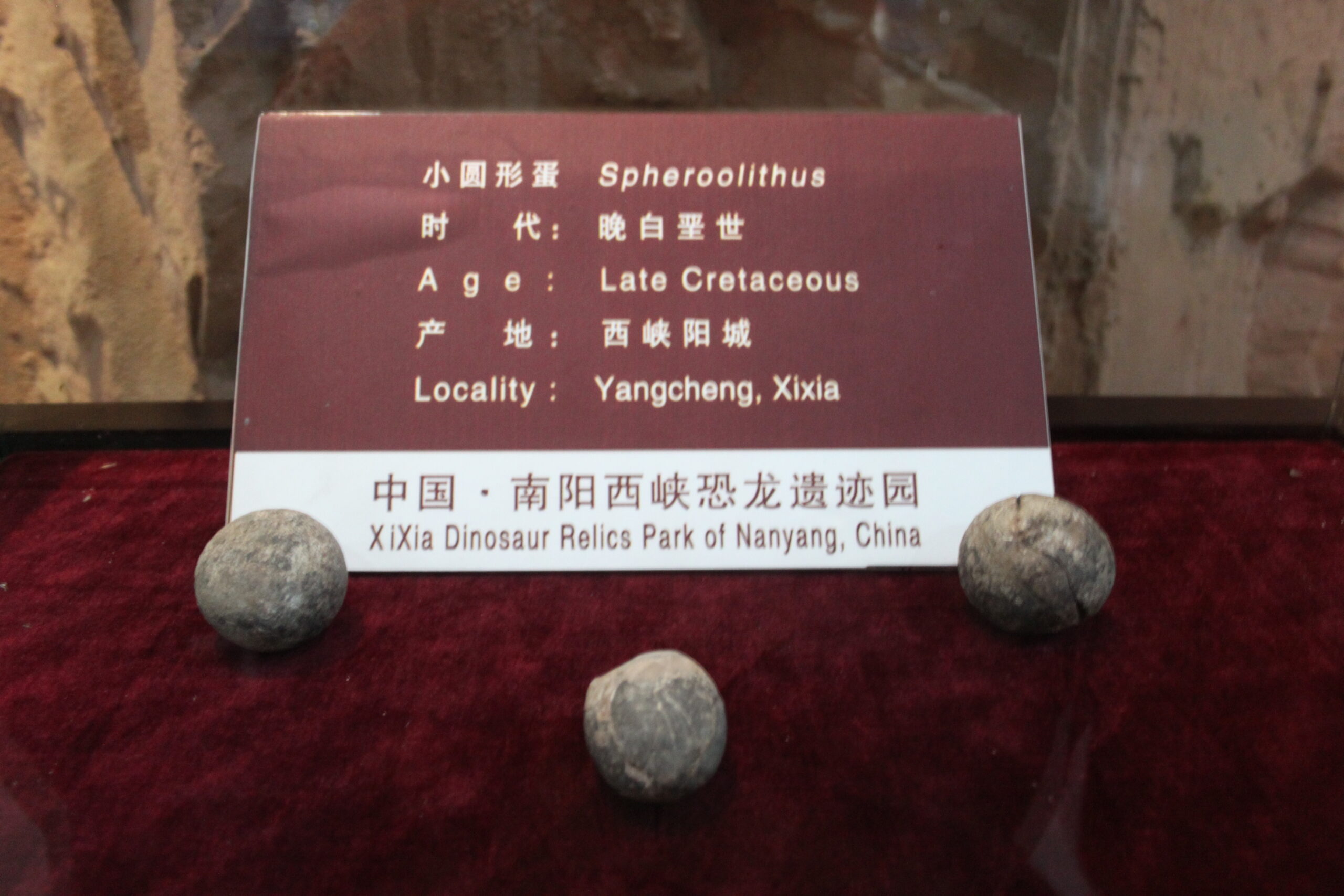

Researchers focused on two species representing opposite ends of the dinosaur size spectrum: Protoceratops, a pig-sized dinosaur with small eggs weighing 194 grams, and Hypacrosaurus, a massive duck-billed dinosaur with eggs weighing over 4 kilograms. These specimens came from some of paleontology’s most famous fossil sites.

The Protoceratops embryos were discovered in Mongolia’s Gobi Desert during expeditions by the American Museum of Natural History and Mongolian Academy of Sciences, with at least 12 eggs containing embryos and 6 preserving nearly complete skeletons. The Hypacrosaurus specimens came from Alberta, Canada, representing some of the largest known dinosaur eggs.

Counting Days Through Microscopic Analysis

Scientists first used CT scanning to visualize the developing teeth within embryonic jaws, then employed advanced microscopy to examine the pattern of von Ebner lines in the tooth material. This painstaking process required extracting tiny jawbones from the precious fossils and creating paper-thin cross-sections for examination.

The measurements revealed von Ebner line spacing of approximately 10 micrometers in Protoceratops embryos and 15 micrometers in Hypacrosaurus specimens. By counting these microscopic daily growth markers, researchers determined that Protoceratops embryos were about three months old when they died, while Hypacrosaurus embryos had been developing for six months.

Shattering Previous Assumptions

Scientists had long assumed that dinosaur incubation periods resembled those of modern birds, whose eggs hatch within 11 to 80 days. The new findings completely overturned this theory. Instead of quick hatching times, dinosaur eggs took between 3 and 6 months , twice as long as predicted from bird eggs of similar size.

This discovery suggests that dinosaur incubation was more similar to that of modern reptiles than birds. Comparable-sized reptilian eggs typically take twice as long as bird eggs , spanning weeks to many months. The research indicates that rapid incubation evolved later in birds, likely after they had already separated from other dinosaur lineages.

The Science Behind Daily Growth Rings

During embryonic tooth formation, liquid dentin fills the inside of developing teeth, mineralizing each night and creating daily growth lines called von Ebner lines. Eventually, dentine completely fills the tooth and these lines stop forming, but while active, they can be counted like tree rings to determine tooth-formation times.

The technique was validated using crocodilians, which are the closest living relatives to dinosaurs and the most suitable model for studying dinosaur tooth formation. These incremental lines of von Ebner form daily in most species, representing the ancestral rate for the entire group.

Implications for Dinosaur Biology and Behavior

The extended incubation periods revealed profound implications for dinosaur life strategies. Prolonged incubation exposed eggs and their parents to increased risks from predators, starvation, and other environmental dangers. Parents had to remain in one location without succumbing to deteriorating conditions for as long as a year, reproducing at much slower rates than birds or mammals.

The findings also challenged theories about dinosaur migration patterns, making it unlikely that some dinosaurs could nest in temperate regions like Canada and then travel to Arctic areas during summer. The time required for hatching would have severely limited seasonal movement capabilities compared to modern migratory species.

The Connection to Mass Extinction

Compared to animals with faster incubation times, dinosaurs’ lengthy development periods would have placed them at a distinct disadvantage following the asteroid impact that ended the Cretaceous period. These warm-blooded creatures required considerable resources to reach adult size, took more than a year to mature, and had slow incubation times.

The long incubation periods likely made it difficult for dinosaurs to compete with faster-reproducing animals such as modern birds and mammals in the aftermath of mass extinction. Slower generation times and higher exposure to predation may have disadvantaged them when competing for limited resources during the rapid climatic changes at the end of the Cretaceous.

Comparing Ancient and Modern Reproduction

An ostrich hatchling emerges from its egg after 42 days, while humans typically give birth after nine months. In contrast, the small Protoceratops embryos were nearly three months old, while the larger Hypacrosaurus embryos were nearly six months old. This places dinosaur development closer to large modern reptiles than to their bird descendants.

In birds, rapid incubation periods compensate for limitations such as small clutch sizes and having only a single functioning ovary, helping them avoid prolonged exposure to predation and environmental dangers while allowing time for migration. Dinosaurs apparently lacked these evolutionary adaptations.

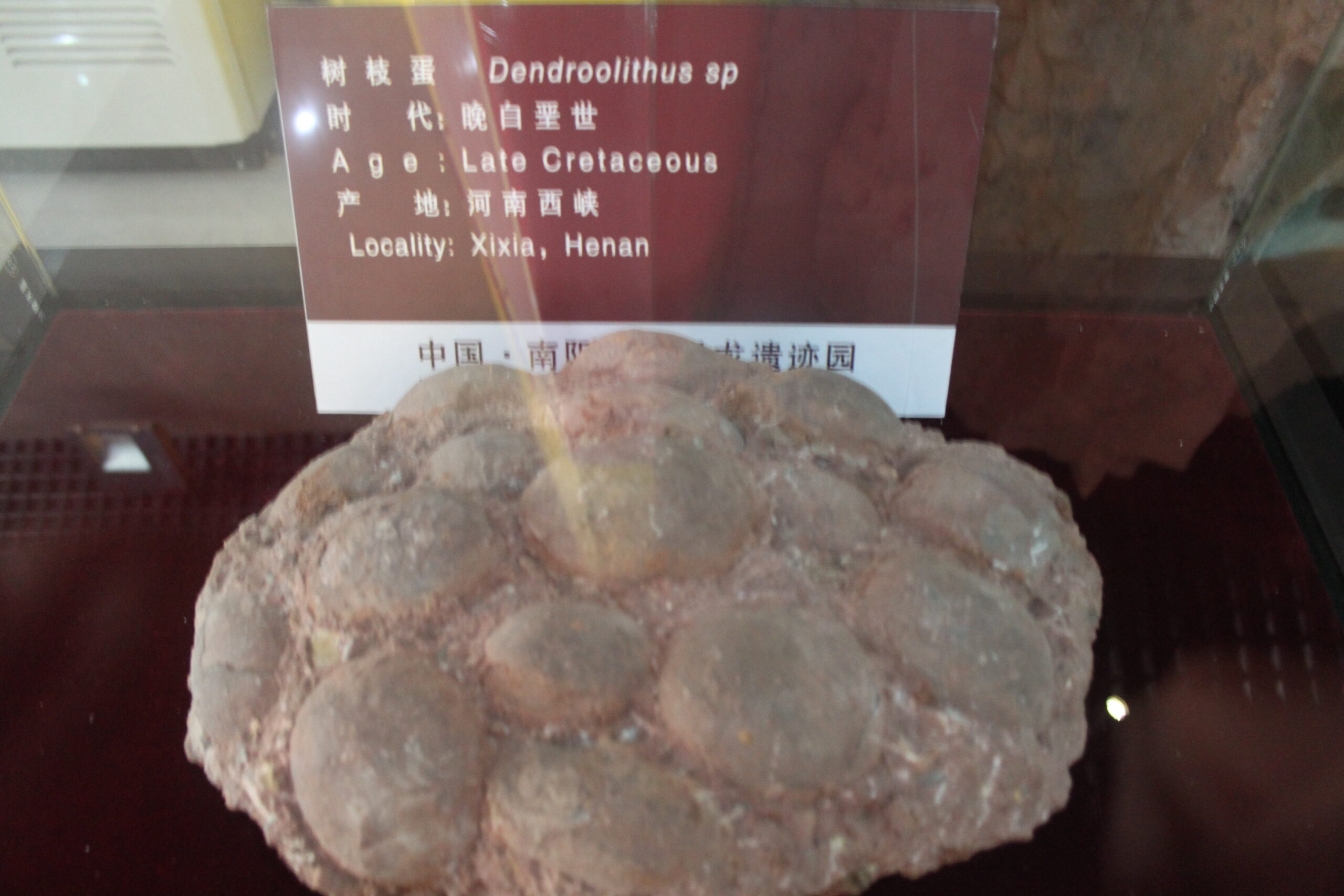

The Rarity of Embryonic Fossils

Embryonic fossils represent crucial developmental stages that are poorly understood because dinosaur embryos are exceptionally rare specimens. These embryonic remains represent some of the best fossils in the world, collected during spectacular American Museum expeditions to Mongolia’s Gobi Desert and studied using cutting-edge technology.

Some of the most significant specimens come from the Tugriken Shireh locality, discovered during Mongolian-Japanese paleontological expeditions. The Protoceratops nest was the first to be attributed with certainty to a ceratopsian dinosaur, and the eggs’ small size makes them the smallest proven non-avian dinosaur eggs yet discovered.

Broader Implications for Understanding Evolution

The discovery suggests that rapid avian incubation evolved much later than previously thought, possibly around the origin of flight roughly 150 million years ago, or perhaps even afterwards. This timing would explain how modern birds developed their competitive advantages over other egg-laying animals.

Scientists hope to examine theropod dinosaurs like Velociraptor, which are closer relatives to modern birds, to determine when fast incubation evolved and whether this trait gave early birds better survival odds during the end-Cretaceous extinction.

Conclusion: Rewriting Dinosaur History

The revelation that dinosaurs required months rather than weeks fundamentally changes our understanding of these magnificent creatures. Their reproductive strategy resembled modern reptiles more than their bird descendants, creating vulnerabilities that may have contributed to their extinction when environmental conditions rapidly changed.

This research demonstrates how microscopic details preserved in fossils can unlock major secrets about prehistoric life. The daily growth rings in embryonic teeth have opened an entirely new window into dinosaur biology, revealing just how different the ancient world truly was from today. What other secrets might these ancient time capsules still hold?