Walking in the muddy sand along a prehistoric lakeshore, creatures from millions of years ago left behind something remarkable. Their footsteps, pressed into the earth for just moments, would become frozen in time through an extraordinary process that transformed soft sediment into stone. These now speak to us across vast stretches of time, revealing intimate details about lives lived long before humans ever walked the earth.

Think of footprints as nature’s ancient diary entries. Unlike bones that can be carried far from where an animal lived, footprints mark the exact spot where a creature once moved through its world. Fossilised bones aren’t necessarily found where the animal lived, they could have been washed to a new location. But tracks were made by a dinosaur moving about its environment – so they are an important link between these prehistoric animals and the habitats they lived in. Every step tells a story of intention, of purpose, of life in motion. Let’s dive into the incredible tales these ancient traces reveal.

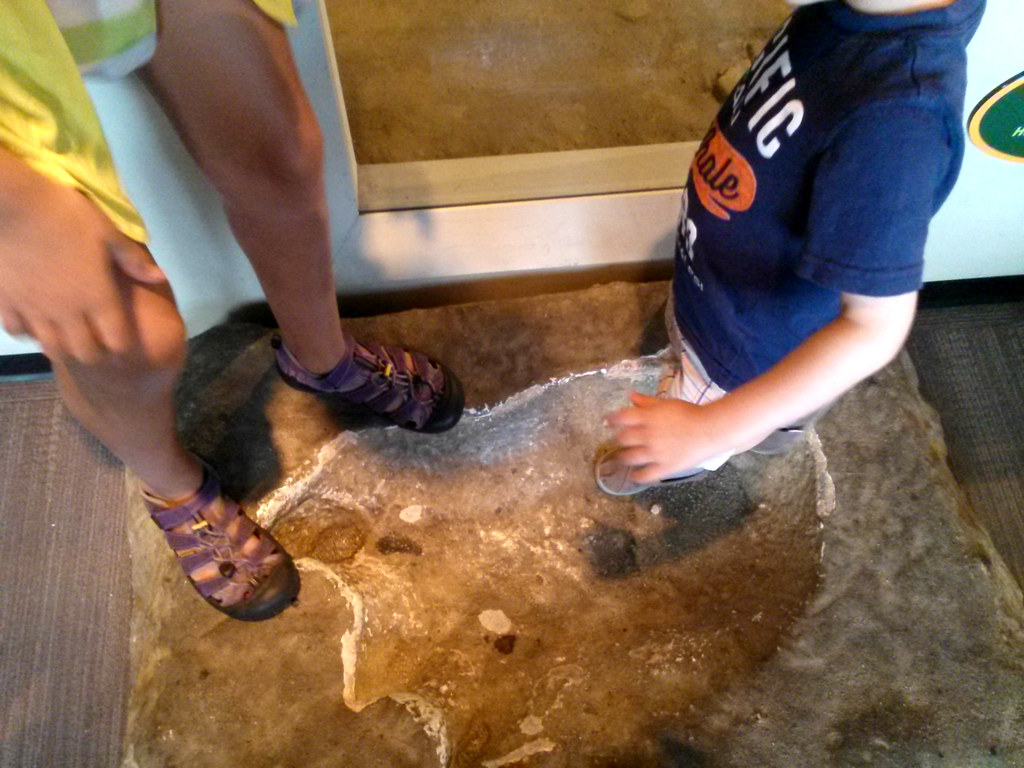

The Moment Two Human Ancestors Crossed Paths

Picture this extraordinary scene from one and a half million years ago in Kenya. More than 1.5 million years ago, two different species of ancient human crossed paths on a lakeshore, perhaps locking eyes with each other. Two different species of early humans walked along the muddy shores of Lake Turkana, their footsteps preserved in what would become one of paleontology’s most stunning discoveries.

A stunning discovery of fossilized footprints pressed into soft mud preserved the unexpected and extraordinary moment, suggesting that the two distinct types of hominin were able to live as neighbors sharing a habitat, rather than as competitors who kept to their own territory. The tracks belonged to Homo erectus, a direct ancestor of modern humans, and Paranthropus boisei, a more robust early human species. What makes this find so captivating is the timing. The researchers said they are confident that the tracks were imprinted within hours to a few days of one another because there is no cracking on the surface of the footprints, which would be the case if they were exposed to air and dried under the sun for a longer period.

Dinosaur Highways Reveal Ancient Behaviors

Dinosaurs were prolific storytellers, leaving behind trackways that stretch for hundreds of meters across ancient landscapes. They form five extensive trackways, with the longest stretching for more than 150 metres. Four of the trackways were made by a species of gigantic, long-necked, herbivorous sauropod. These prehistoric highways tell us far more than bones ever could about how these massive creatures lived their daily lives.

Most of the giants were moving northeast at an average speed of around 5 kilometers per hour (3 miles per hour), which is comparable to the pace of a human walking, Edgar said. The trackways reveal social patterns too. A series of parallel tracks may suggest that animals were moving in a group and could indicate possible herd behaviour. Some sites show evidence that predators might have been stalking herbivore herds, though scientists must be careful not to assume direct interaction since the tracks could have been made hours or days apart.

The sheer number of tracks at some locations is staggering. The 66 fossilized footprints, which range in size from about 5 centimeters to 20 centimeters (about 2 to 8 inches) in length, reveal that the dinosaurs had likely been crossing a river or going up and down the length of a river, Romilio said.

When Ancient Birds Left Their Mark

Bird footprints present some of the most delicate and intriguing traces in the fossil record. About 50 million years ago, a small bird waded along a lakeshore in what today is central Oregon. A worm wriggled at its feet. The bird appeared to probe the silty earth with its beak, once, twice, three times, looking for food. This incredibly detailed behavioral snapshot was preserved through the careful study of tiny footprints and associated markings.

Two small bird footprints found within 50 million-year-old lakebed sediments suggest the feeding behavior of a shorebird foraging for worms in shallow water, according to the study. Researchers discovered small round indentations near the bird tracks that initially puzzled them. At first, Bennett and study coauthor Dr. Nicholas A. Famoso – the head paleontologist and museum curator at John Day – thought they could be caused by raindrops, which can leave impressions in the fine grains of shale and clay the tracks were found in. But there are usually many raindrop impressions, and here there were only a few, and only near the footprints. The researchers wondered whether the bird had made them with its beak.

Even more remarkable are bird-like tracks from much earlier periods. The most ancient of these footprints, at over 210 million years old, are 60 million years older than the earliest known body fossils of true birds. It’s possible that these tracks were produced by early dinosaurs, and potentially even early members of a near-bird lineage, but the authors note that there could also have been other reptiles, cousins of dinosaurs, that convergently evolved bird-like feet.

Mammalian Traces Tell Survival

Ancient mammal tracks reveal the secretive lives of our distant relatives who shared the world with dinosaurs and later dominated the landscape. They also found evidence of a cat-like predator dating to roughly 29 million years ago. A set of paw prints, discovered in a layer of volcanic ash, likely belonged to a bobcat-sized, saber-toothed predator resembling a cat – possibly a nimravid of the genus Hoplophoneus. These fossil pawprints tell us about predator behavior and anatomy in ways bones cannot.

Since researchers didn’t find any claw marks on the paw prints, they suspect the creature had retractable claws, just like modern cats do. This detail suggests that retractable claws evolved much earlier than previously thought. Meanwhile, A set of three-toed, rounded hoofprints indicate some sort of large herbivore was roaming around 29 million years ago, probably an ancient tapir or rhinoceros ancestor.

The oldest evidence of human presence in the Americas comes from footprints rather than bones. In 2021 they were radiocarbon dated, based on seeds found in the sediment layers, to between 21,000 and 23,000 years ago. That date range is currently the subject of scientific debate, but if it is correct, the footprints would be one of, if not the oldest evidence of humans in the Americas.

The Art of Track Preservation

Creating fossilized footprints requires a perfect storm of conditions that rarely align in nature. For a perfect print, the ground can’t be too hard or too soft. If the ground is too hard, the resulting print would be very shallow, show very limited detail or not form at all. If the ground is too soft, the track could collapse in on itself. The sediment must be just right, with the consistency of thick mud or wet sand.

A dinosaur walked across a mudflat, leaving footprints in the wet sediment. The coming tides covered the tracks with sand, grit, and gravel, protecting them from the detrimental effects of sun, wind, and water. The footprints were buried deeper due to sediment accumulation and hardened into rock through lithification. This process must happen quickly. Tracks exposed to air for too long dry out and crack, making them unrecognizable.

It is important to remember that footprints are fossilized under special conditions. Because most tracks are made in wet sediment, they are often preserved near bodies of water or in areas with shallow water, such as lakebeds. This means that fewer animal tracks are preserved in habitats that are not near bodies of water.

Reading Between the Toes

Scientists have developed sophisticated methods for interpreting the hidden in fossilized footprints. Over the years, many ichnites have been found, around the world, giving important clues about the behaviour (and foot structure and stride) of the animals that made them. For instance, multiple ichnites of a single species, close together, suggest ‘herd’ or ‘pack’ behaviour of that species. Combinations of footprints of different species provide clues about the interactions of those species.

Speed calculations reveal surprising insights about ancient locomotion. With scientific analysis, dinosaur specialists are now analyzing tracks for the walking-speeds, or sprint-running speeds for all categories of dinosaurs, even to the large plant eaters, but especially the faster 3-toed meat hunters. The largest sauropods moved at a leisurely pace comparable to human walking speed, while smaller theropods could achieve much greater speeds.

Unlike bones, which can be transported to different areas by wind, water or scavengers, footprints remain in the exact locations where they were made. Tracks not only indicate the size of the dinosaurs but also provide clues about their behavior, such as group dynamics and predator-prey interactions. If well-preserved, the impressions can also shed light on how these creatures reacted to environmental changes, according to Tanner.

Traces of Fear and Hunting

Some of the most dramatic come from trackways that capture moments of predator-prey interaction. First, one set of prints appears to show human hunters tracking a giant sloth. Variations in the tracks left by the sloth show that it stood on its hind legs and spun around, possibly showing fear, but there is no evidence that the hunt was successful. This 20,000-year-old scene from White Sands National Park preserves what might be humanity’s earliest documented hunting strategy.

Researchers noted that the Megalosaurus path intersected with the sauropod trackways, suggesting the predator moved through the area shortly after the herbivores. However, scientists must be cautious about inferring direct chase scenes. Some experts propose that some trackways with prints made by different types of dinosaurs are evidence of prehistoric chase scenes. However, predator and prey prints in the same place may have been made hours or even weeks apart.

The evidence for pack hunting behavior in dinosaurs comes largely from trackway analysis. Evidence of herding, as well as pack hunting are also being investigated. Multiple parallel trackways suggest coordinated group movement, though distinguishing between herding and hunting requires careful analysis of track spacing, direction, and timing.

Microscopic Details, Monumental Discoveries

Modern technology has revolutionized how scientists study fossilized footprints, revealing details invisible to the naked eye. Scientists then built detailed 3D models of the site using drone photography to document the footprints in detail for further research. The preservation of these latest fossils is so detailed that researchers can see how the mud was deformed as the dinosaurs trod across the soft ground. The scientists have taken more than 20,000 images of the footprints. This will allow them to find out more about the lives of these reptiles, such as how they walked, how fast they were travelling, how large they were and whether they were alone or in a group.

Natural casts are like three-dimensional replicas of an animal’s foot. As such, they can preserve informative foot details (such as skin impressions) just like true tracks. Some exceptionally well-preserved tracks show skin texture, toe pads, and even claw marks. These microscopic details help scientists understand not just what animals looked like, but how they moved and behaved.

Trace fossils can fill in gaps in the fossil record, said Dr. Anthony Martin, professor of practice in the department of environmental sciences at Emory University in Atlanta. “This paper has tracks that are definitely from a bird of some sort, and then tracks that are definitely from a lizard,” said Martin, who researches modern and fossil traces and was not involved in the research. “So those are showing that those animals actually were there, even though there’s not a single bone or feather or any other bodily evidence of those two types of animals being there.”

Fossilized footprints offer us something no other fossil can: a direct connection to the living, breathing moments of ancient life. These traces capture split-second decisions, daily routines, and life-or-death encounters frozen in stone. From the tentative steps of early human ancestors to the thunderous migrations of dinosaur herds, each track tells us that these weren’t just anatomical specimens, but real animals with behaviors, fears, and purposes. “It’s like a snapshot into the day of the (dinosaurs’) life, and what they were doing,” Edgar said. What do you think remain hidden in the rocks beneath our feet, waiting to be discovered?