Imagine discovering the fossil of a creature that fundamentally changed our understanding of life itself. Cetaceans (whales, dolphins, and porpoises) are an order of mammals that originated about approximately 48.5 million years ago in the Eocene epoch. What seems impossible today was reality millions of years ago: Early ancestors of modern whales once walked on four legs. One relative of whales was Pakicetus, which lived approximately 48.5 million years ago.

You might think whales have always been ocean dwellers, but the truth is far more remarkable. Whales and their kin evolved from land-dwelling mammals, a transition that entailed major physiological and morphological changes – which geneticists have begun to parse. Going back to being aquatic was a drastic move that would change the animals inside and out, in the space of about 10 million years – an eyeblink in evolutionary terms. So let’s dive into this incredible story of transformation.

The First Walking Whale: Meet Pakicetus

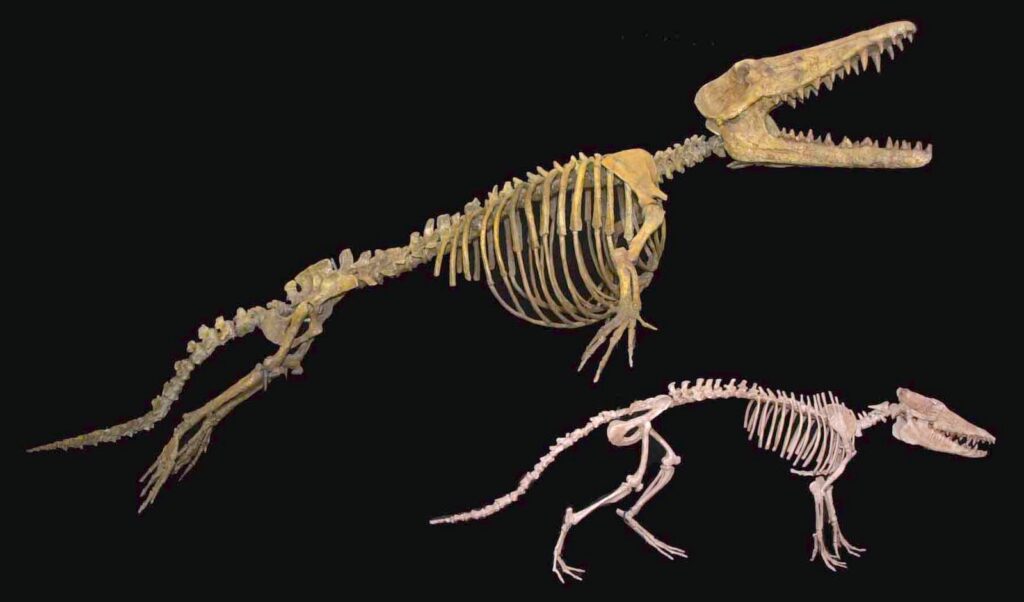

Pakicetus (meaning ‘whale from Pakistan’) is an extinct genus of amphibious cetacean of the family Pakicetidae, which was endemic to South Asia during the Ypresian (early Eocene) period, about 48.5 million years ago. It was a wolf-like mammal, about 1–2 m (3 ft 3 in – 6 ft 7 in) long, and lived in and around water where it ate fish and other animals. Think of a creature that looks nothing like what you’d expect from a whale ancestor.

Pakicetus looked very different from modern cetaceans, and its body shape more resembled those of land-dwelling hoofed mammals. Unlike all later cetaceans, it had four fully functional long legs. Pakicetus had a long snout; a typical complement of teeth that included incisors, canines, premolars, and molars; a distinct and flexible neck; and a very long and robust tail. Yet this seemingly ordinary land mammal held extraordinary secrets in its anatomy.

The Aquatic Hunter’s Lifestyle

Straddling the two worlds of land and sea, the wolf-sized animal was a meat eater that sometimes ate fish, according to chemical evidence. Well-developed puncturing cusps (incisors) and serrated cheek teeth indicate that Pakicetus ate flesh, most likely that of fish. This wasn’t just a theory based on guesswork.

Samples from the teeth of Pakicetus yield oxygen isotope ratios and variation that indicate Pakicetus lived in freshwater environments, such as rivers and lakes. Despite being primarily a land animal, it is believed that Pakicetus lived in and around freshwater environments and hunted fish, using an ambush strategy due to its limited speed. Picture this predator waiting patiently in shallow waters, ready to strike at unsuspecting prey swimming by.

Ears That Changed Everything

Here’s where the story gets fascinating. Pakicetus was classified as an early cetacean due to characteristic features of the inner ear found only in cetaceans (namely, the large auditory bulla is formed from the ectotympanic bone only). Thus the thickened bulla of Pakicetus is interpreted as a specialization for hearing underwater sound.

Like all other cetaceans, Pakicetus had a thickened skull bone known as the auditory bulla, which was specialized for underwater hearing. Based on this, Pakicetus retained the ability to hear airborne sound. This remarkable adaptation allowed them to hunt effectively in both environments, giving them a significant advantage over purely terrestrial or aquatic competitors.

The Walking Whale: Ambulocetus Appears

Ambulocetus (from Latin ambulō, meaning “to walk”, and cetus, meaning “whale”, and thus, “walking whale”) is a genus of early amphibious cetacean from the Kuldana Formation in Pakistan, roughly 48 or 47 million years ago during the Early Eocene (Lutetian). It contains one species, Ambulocetus natans (Latin natans “swimming”), known solely from one near-complete skeleton.

Ambulocetus is among the best-studied of Eocene cetaceans, and serves as an instrumental find in the study of cetacean evolution and their transition from land to sea, as it was the first cetacean discovered to preserve a suite of adaptations consistent with an amphibious lifestyle. Compared to other early whales, like Indohyus and Pakicetus, Ambulocetus looks like it lived a more aquatic lifestyle. Its legs are shorter, and its hands and feet are enlarged like paddles. It is thought to have swum much like a modern river otter, tucking in its forelimbs while alternating its hind limbs for propulsion, as well as undulating the torso and tail.

Between Two Worlds: Amphibious Adaptations

On land, Ambulocetus may have walked much like a sea lion. While on land, Ambulocetus could support its own weight on its limbs but was not a runner like a wolf. The large, broad feet of Ambulocetus hint that it moved more like an otter or sea lion on land than its terrestrial ancestors. This creature truly lived between worlds, equally at home in water and on land.

The hypothesis that Ambulocetus lived an aquatic life is also supported by evidence from stratigraphy – Ambulocetus’s fossils were recovered from sediments that probably comprised an ancient estuary – and from the isotopes of oxygen in its bones. The isotopes show that Ambulocetus likely drank both saltwater and freshwater, which fits perfectly with the idea that these animals lived in estuaries or bays between freshwater and the open ocean. Scientists can literally taste the ancient environments these creatures inhabited through chemical analysis.

The Evolutionary Experiment: Protocetids

Trunk and limb proportions of early middle Eocene Rodhocetus are most similar to those of the living, highly aquatic, foot-powered desmans. With its pointed snout, sharp teeth, short legs and robust tail, Rodhocetus may have looked something like a 10-foot-long crocodile with fur. According to Gingerich, it is the oldest whale ever found with the flexible back and heavily muscled tail needed for efficient swimming.

Living at about the same time as the remingtonocetids was another group of even more aquatically adapted whales, the protocetids. These forms, like Rodhocetus, were nearly entirely aquatic, and some later protocetids, like Protocetus and Georgiacetus, were almost certainly living their entire lives in the sea. The evolutionary experiments were becoming increasingly successful, with each generation better adapted to marine life.

The Ocean Giants: Basilosaurus Rules the Seas

Basilosaurus (meaning “king lizard”) is a genus of large, predatory, prehistoric archaeocete whale from the late Eocene, approximately 41.3 to 33.9 million years ago (mya). First described in 1834, it was the first archaeocete and prehistoric whale known to science. At 45 feet long, Basilosaurus was as big as a modern humpback whale, but much slimmer. Remains from the long, slender mammal were thought by early scientists to be from a prehistoric sea serpent.

Basilosaurus would have been the top predator of its environment. But within a few million years whales had passed the point of no return: Basilosaurus, Dorudon, and their relatives never set foot on land, swimming confidently on the high seas and even crossing the Atlantic to reach the shores of what is now Peru and the southern United States. Their bodies adjusted to their exclusively aquatic lifestyle, forelimbs shortening and stiffening to serve as flippers for planing, tails broadening at the tip in horizontal flukes to create a hydrofoil. Yet like talismans from a long-forgotten life ashore, their hind legs remained, complete with tiny knees, feet, ankles, and toes, useless now for walking but good perhaps for sex.

The Smaller Predator: Dorudon’s Success Story

Dorudon (“spear-tooth”) is a genus of extinct basilosaurid ancient whales that lived alongside Basilosaurus 41.03 to 33.9 million years ago in the Eocene. Dorudon was a medium-sized whale, with D. atrox reaching 5 metres (16 ft) in length and 1–2.2 metric tons (1.1–2.4 short tons) in body mass. Dorudon more closely resembles a modern toothed whale, with a size and shape like an orca.

Unlike other early whales which moved much like an eel, Dorudon relied on moving its tail, or fluke, up and down to propel it through the water, much like how today’s dolphins swim. Gingerich thinks that Dorudon likewise calved in the shallows, because there are unusual numbers of juvenile skeletons at the site. Some of the baby Dorudon have bite marks on their heads, likely inflicted by hungry Basilosauruses. Even in ancient oceans, the struggle between predator and prey painted a dramatic picture.

The Final Transformation: From Walking to Swimming

Thus it appears that the land-to-sea transition in whale evolution involved at least two distinct phases of locomotor specialization: (1) hindlimb domination for drag-based pelvic paddling in protocetids (Rodhocetus), with tail elongation for stability, followed by (2) lumbus domination for lift-based caudal undulation and oscillation in basilosaurids (Dorudon). The transition wasn’t a simple linear progression but involved multiple evolutionary strategies.

These vestigial hindlimbs are evidence of basilosaurids’ terrestrial heritage. Basilosaurus and Dorudon were fully aquatic whales (like Basilosaurus, Dorudon had very small hind limbs that may have projected slightly beyond the body wall). They were no longer tied to the land; in fact, they would not have been able to move around on land at all. Their size and their lack of limbs that could support their weight made them obligate aquatic mammals, a trend that is elaborated and reinforced by subsequent whale taxa.

Conclusion

The story of walking whales represents one of evolution’s most dramatic transformations, completed in what scientists consider an evolutionary eyeblink. From wolf-sized Pakicetus hunting fish in ancient Pakistani rivers to massive Basilosaurus ruling Eocene oceans, these creatures bridged an impossible gap between land and sea. Their fossilized remains don’t just tell us about ancient life – they reveal the incredible adaptability of nature itself.

What do you think about this amazing journey from land to sea? Tell us in the comments.