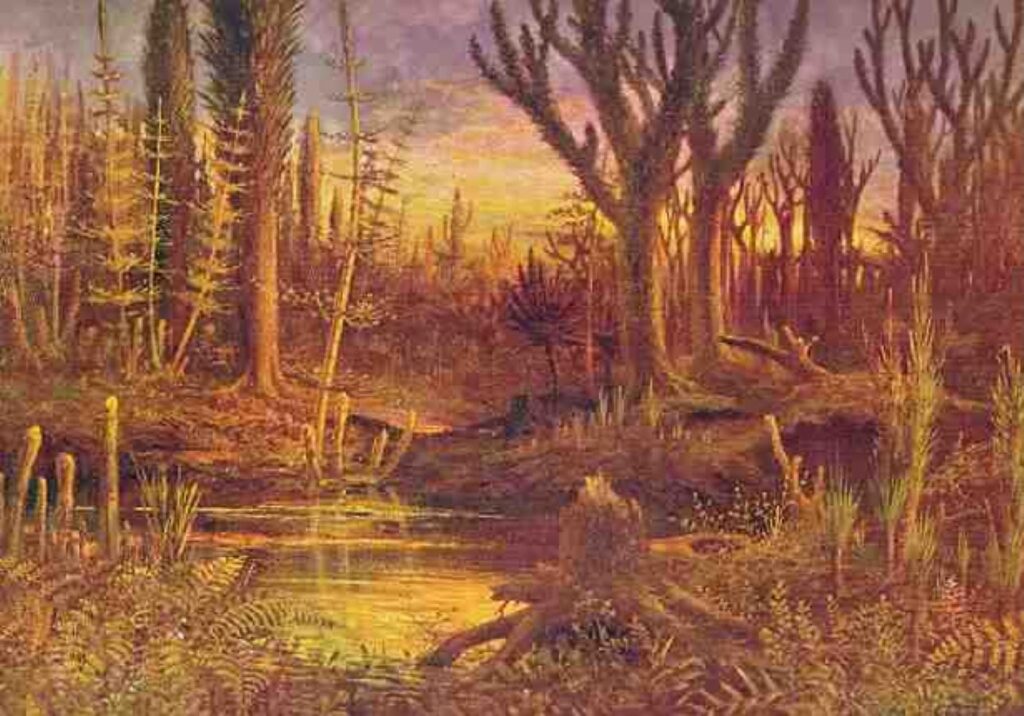

Picture yourself standing in a misty primordial landscape roughly four hundred million years ago. The ground beneath your feet isn’t covered in familiar grass or flowers, but rather a carpet of bizarre bacterial mats and primitive algae. You scan the horizon, expecting to see nothing taller than a few feet, when suddenly your eyes fall upon towering spires stretching nearly thirty feet into the prehistoric sky. These aren’t trees, as you might expect, but something far stranger. Giant fungi known as Prototaxites once dominated Earth’s landscapes in an era when the tallest plants barely reached your waist.

This forgotten chapter in Earth’s history reveals a world so alien it seems like science fiction, yet it’s rooted in remarkable scientific discovery. Let’s journey back to when mushroom-like titans ruled the planet and uncover the mysteries of these ancient fungal forests.

The Dawn of Terrestrial Giants

Prototaxites emerged during the Late Silurian and thrived until the Late Devonian periods, forming large trunk-like structures up to one meter wide and reaching eight meters in length, making it by far the largest land-dwelling organism of its time. Think about that for a moment – while the tallest plants of the era were no bigger than modern houseplants, these mysterious organisms towered like skyscrapers.

By far the largest land organism at the beginning of this period was the enigmatic Prototaxites, which was possibly the fruiting body of an enormous fungus, rolled liverwort mat, or another organism of uncertain affinities that stood more than eight meters tall. Around 420 million years ago, the tallest plants on land stood only a few feet high, yet Prototaxites towered up to 8 meters tall and 3 meters wide.

The sheer scale of these organisms becomes even more remarkable when you consider their environment. Back then, no animals with backbones lived on land; there were only millipedes, wingless insects and worms. Imagine wandering through this primordial world, where your footsteps would crunch on bacterial mats while these colossal fungal pillars loomed overhead, casting shadows across an otherwise diminutive landscape.

The Scientific Mystery That Captivated Generations

When the first Prototaxites fossils emerged from the earth in the 1840s, they sparked one of paleontology’s most enduring debates. Prototaxites was discovered in 1843, but it was not until 1859 that Canadian geologist John William Dawson described it as fossilized rotting wood from conifers, with its translated name “first yew” referencing the conifer family Taxaceae.

Prototaxites confounded experts for over 130 years, with debate raging as some scientists called it a lichen, others a fungus, and still others clung to the notion that it was some kind of tree, while analyses of the fossils were inconclusive. The mystery deepened because these trunk-like structures appeared in rock layers from a time when true trees didn’t exist.

As one researcher noted, the problem was that when you looked up close at the anatomy, it was evocative of many different things, but diagnostic of nothing, with the added challenge that whenever someone suggested what it might be, everyone else would object with questions like “How could you have a lichen 20 feet tall?”

Breakthrough Through Chemical Fingerprints

The breakthrough that finally solved this ancient puzzle came through an unlikely approach: chemistry. A 2007 study by Hueber, Boyce and others suggested they had found the evidence through chemical analysis, examining the ratio of carbon-12 and carbon-13 in fossil Prototaxites samples, finding the ratio to be significantly different from plants and supporting the fungi hypothesis.

Because plants obtain their carbon from carbon dioxide in the air, they tend to have similar carbon isotope ratios as other plants of the same type, while animals have ratios similar to what they eat, but the research team found that Prototaxites displayed a much wider-ranging isotope ratio than any known plant, confirming it was a fungus.

This chemical detective work revolutionized our understanding of these ancient giants. Rather than being plants that photosynthesized like modern trees, Prototaxites obtained its carbon by consuming organic matter, just like fungi do today. The mystery that had puzzled scientists for over a century finally had its answer.

Life in the Alien Devonian World

The world where Prototaxites thrived was utterly unlike anything we see today. By the start of the Devonian, early terrestrial vegetation had begun to spread, but these plants did not have roots or leaves like most plants today, with many having no vascular tissue at all, probably spreading vegetatively rather than by spores or seeds and not growing much more than a few centimeters tall.

The earliest land plants such as Cooksonia consisted of leafless, dichotomous axes with terminal sporangia and were generally very short-statured, growing hardly more than a few centimeters tall. Almost from the first, the plants were not isolated pioneers but members of small, mixed communities, fledgling ecosystems in which springtails, trigonotarbids, insects, centipedes and millipedes played their part.

Picture this landscape: vast stretches of muddy floodplains dotted with tiny green stems, where primitive arthropods scuttled between patches of algal mats. The world’s most humongous fungus grew on an alien Earth landscape around pools of carbon-rich water surrounded by stumpy proto-trees and bushes, millipedes, wingless insects, and worms. In this bizarre ecosystem, Prototaxites stood like ancient monuments, utterly dominating the skyline.

How Giant Fungi Fed and Survived

Understanding how these massive organisms sustained themselves reveals fascinating insights into ancient ecosystems. Research suggests that a fossilized, twenty-foot-tall fungus that towered over Earth’s landscape 400 million years ago likely thrived not by feeding on plants – as modern fungi largely do – but rather relied on carbon-rich microbial mats in floodplain environments, which helps solve the long-running mystery about how the fungus could have grown so big in an environment largely devoid of host plants.

When it lived during Earth’s early Devonian period, the vascular plants common today were just beginning to populate the landscape, with these vascular plants dwarfed by Prototaxites and consisting of just simple stems with no roots or leaves – hardly a sufficient food source to grow the giant fungus.

Think of Prototaxites as nature’s first recycling specialists. While modern fungi often decompose fallen logs and leaf litter, these ancient giants had to make do with whatever organic matter was available in their sparse world. They likely fed on bacterial mats, primitive algae, and the occasional dead plant material, efficiently extracting nutrients from this limited buffet to fuel their remarkable growth.

The Mysterious Structure and Growth Patterns

Recent research has revealed surprising details about how these giants actually grew and functioned. A 2022 paper proposed that Prototaxites was a complex fungal rhizomorph rather than a towering, upright structure, instead exhibiting a more varied growth pattern including horizontal and subterranean expansion, with its primary function being the redistribution of water, nutrients, and oxygen across early terrestrial ecosystems, facilitating the survival and spread of vegetation in nutrient-poor environments.

The organism consisted of skeletal tubes twenty to fifty micrometers across with thick walls that were undivided for their length, along with thinner generative filaments that branched frequently and meshed together to form the organism’s matrix, with these thinner filaments being septate and bearing internal walls with germ pores, a trait only present in modern red algae and fungi.

This intricate internal architecture suggests that Prototaxites weren’t just simple mushroom-like structures but complex organisms with sophisticated transport systems. They may have functioned like underground networks, connecting different parts of early ecosystems and helping to distribute vital resources across the barren landscape.

Ancient Interactions and Ecosystem Relationships

Evidence suggests these fungal giants didn’t exist in isolation but formed complex relationships with other organisms. Prototaxites mycelia were fossilized as they invaded the tissue of vascular plants, and there is evidence of animals inhabiting Prototaxites, with mazes of tubes found within some specimens, though evidence of arthropod boreholes from the early and late Devonian suggests the organism survived such boring stress for many millions of years, with boreholes appearing long before plants developed structurally equivalent woody stems.

The earliest known insect, Rhyniella praecusor, was a flightless hexapod with antennae and a segmented body, with fossil Rhyniella being between 412 million and 391 million years old. These primitive insects may have been among the first creatures to discover that giant fungi provided both shelter and food resources.

The relationship between Prototaxites and early animals appears to have been mutually beneficial in some cases. While some creatures bored into the fungal tissue for shelter or food, the fungi seemed resilient enough to survive and even regrow around these intrusions, creating complex internal labyrinths that provided habitat for early terrestrial life.

The Fall of the Fungal Titans

Prototaxites became extinct in the Late Devonian as vascular plants rose to prominence. The end of the fungal era wasn’t sudden but rather a gradual shift as Earth’s ecosystems transformed dramatically. By the Middle Devonian, shrub-like forests of primitive plants existed including lycophytes, horsetails, ferns, and progymnosperms that evolved with most having true roots and leaves and many being quite tall, with the earliest-known trees appearing in the Middle Devonian.

By about 385 million years ago, plants had developed true roots, leaves, and the ability to grow into actual trees, and once these leafy competitors took hold, Prototaxites began to disappear as trees rose up, creating dense canopies that blocked sunlight, altered the climate, and transformed the land into lush green ecosystems, with fungi like Prototaxites no longer having the open, sunny, and wind-swept environment that made their towering form advantageous.

The rise of true forests marked the end of an era. Where once fungal spires dominated open landscapes, dense woodlands now cast deep shadows and created entirely new ecological niches. The Age of Fungi gave way to the Age of Trees, forever changing the face of our planet.

Modern Mysteries and Scientific Debate

Even today, questions about these ancient giants continue to intrigue researchers. Recent research suggests that Prototaxites may actually have been part of a totally different kingdom of life, separate from fungi, plants, animals and protists, with researchers concluding that Prototaxites was not a fungus and instead proposing it is best assigned to a now entirely extinct terrestrial lineage.

Studies found that the Prototaxites fossils left completely different chemical signatures compared to fungi fossils, indicating that Prototaxites did not contain chitin (a major building block of fungal cell walls), but instead appeared to contain chemicals similar to lignin found in plant wood and bark, leading researchers to suggest it represents a member of a previously undescribed, entirely extinct group of eukaryotes.

This ongoing scientific debate reminds us that our understanding of Earth’s ancient past continues to evolve. Whether Prototaxites were truly fungi, an extinct lineage of unknown organisms, or something else entirely, they represent one of the most remarkable experiments in life’s long history on our planet.

Conclusion: Lessons From the Forgotten Forests

The story of Prototaxites offers us a humbling glimpse into Earth’s deep past, when life took forms so alien they challenge our understanding of what’s possible. These fungal giants dominated landscapes for millions of years, creating the first “forests” on a planet that knew no trees. They remind us that evolution has experimented with countless forms of life, many of which have vanished without a trace.

Today, as we walk through modern forests of oak and pine, maple and fir, it’s worth remembering that our planet once belonged to towering mushroom-like spires. Now dubbed the “Godzilla of Fungi,” Prototaxites offers a window into a land before backboned animals, when giant mushrooms could thrive. These forgotten forests shaped early terrestrial ecosystems and paved the way for the green world we know today.

The next time you spot a humble mushroom growing in the forest, pause for a moment and imagine its ancient relatives stretching toward the sky like prehistoric skyscrapers. In Earth’s four-billion-year history, stranger things than fungal forests have ruled our world. What do you think our planet might look like if these gentle giants had never given way to trees?