Imagine standing in Kansas, surrounded by endless wheat fields and prairie grass, knowing that beneath your feet lie the remnants of an ancient ocean floor. You’re walking over what was once the bottom of a vast inland sea that teemed with marine giants and bizarre creatures unlike anything alive today. The Western Interior Seaway once split the North American continent into two landmasses for 34 million years, from the early Late Cretaceous to the earliest Paleocene.

This lost world wasn’t just any ordinary sea. At its largest extent, the seaway was 2,500 ft deep, 600 mi wide and over 2,000 mi long. Picture a shallow tropical ocean stretching from what is now the Gulf of Mexico all the way to the Arctic Ocean, dividing North America like a massive watery highway. The creatures that called this ancient seaway home were nothing short of spectacular, and their fossilized remains continue to astound scientists today. Let’s dive into this forgotten underwater realm and meet the incredible beings that once ruled these lost oceans.

When North America Was Split in Two

The Western Interior Seaway formed when tectonic forces caused the Pacific and North American plates to collide, resulting in the early phase of growth of the modern Rocky Mountains. This wasn’t a gradual process you might expect. With high eustatic sea levels existing worldwide during the Cretaceous, waters from the Arctic Ocean in the north and the Gulf of Mexico in the south met and flooded the central lowlands.

The landscape transformation was dramatic. The seaway divided North America in two during the end of the age of dinosaurs, with western North America called “Laramidia” and eastern North America called “Appalachia”. Honestly, it’s hard to imagine how different the continent looked back then.

The earliest phase began when an arm of the Arctic Ocean transgressed south over western North America, forming the Mowry Sea, which later merged with a southern embayment to create a completed seaway. This created isolated environments that would prove crucial for the evolution of both land animals and the marine creatures we’re about to explore.

The Shallow Tropical Paradise That Wasn’t

The Western Interior Seaway reached a maximum depth of about 2,500 feet, which was positively shallow compared to the average depth of oceans today at roughly 12,100 feet, meaning the Sun’s life-giving rays touched a significant portion of the water column. This shallow nature created something like a massive tropical lagoon that stretched across the continent.

Widespread carbonate deposition suggests that the Seaway was warm and tropical, with abundant calcareous algae. The water temperatures were surprisingly pleasant. The ocean temperatures of the Western Interior Seaway would have been similar to those in the modern Gulf of Mexico.

Yet beneath the surface, conditions weren’t always ideal for life. During the late Cretaceous, the Western Interior Seaway went through multiple periods of anoxia, when the bottom water was devoid of oxygen and the water column was stratified, but because dead animals decomposed slowly, this favored their preservation as fossils. This oxygen-poor environment proved to be a paleontologist’s dream, creating perfect conditions for fossil preservation.

Mosasaurs: The Ocean’s Ultimate Predators

If you think modern great white sharks are impressive, wait until you meet the mosasaurs. Mosasaurus was a common large predator positioned at the top of the food chain, with paleontologists believing its diet included virtually any animal, likely preying on bony fish, sharks, cephalopods, birds, and other marine reptiles including sea turtles and other mosasaurs.

Tylosaurus reached lengths of over 14 meters (45 feet), while mosasaurs in general could reach lengths of up to 50 feet, roughly the length of a bus. These weren’t just big lizards that happened to live in water. When mosasaurs evolved from a terrestrial lifestyle to a marine one, they developed webbed paddles for swimming, though early ancestors probably weren’t fully marine and likely fed in shallow coastal waters.

The mosasaurs became the biggest predators of the Cretaceous oceans in just 25 million years, a short period in geologic time, after returning to the oceans around 98 million years ago. Their rapid evolution was helped by a stroke of luck when volcanic activity wiped out their main competition, the ichthyosaurs and pliosaurs.

Plesiosaurs: The Long-Necked Sea Serpents

Elasmosaurus platyurus was discovered in 1868 in Kansas and was an ancient marine reptile that thrived in the Western Interior Seaway 80 to 66 million years ago, sharing its habitat with other marine reptiles, fish, sharks, and giant sea turtles. These creatures looked like something straight out of mythology.

Elasmosaurus was between 40 to 50 feet in length, with a wide, flattened body and an extremely long neck that could reach up to 10 meters, double the length of its body. Think of it as nature’s version of the Loch Ness Monster, except this one actually existed. It had over 70 neck vertebrae, more than any other known animal.

Contrary to popular belief, its neck was not highly flexible and was likely used for efficient hunting in the depths of the ocean, with its small head housing large fangs at the front and smaller teeth towards the back. Plesiosaurs were about twenty percent slower than advanced ichthyosaurs but five percent faster than mosasaurids, with long-necked forms built more for manoeuvrability than for speed.

Xiphactinus: The Bully Fish of Ancient Seas

Xiphactinus was one of the largest bony fish ever to have lived and was truly a monster, ranging in size from 15-20 feet and would have looked like a toothy, oversized tarpon. This prehistoric terror earned its fearsome reputation through sheer aggression and an appetite that knew no bounds.

Xiphactinus is often described as a voracious predator that would have fed on whatever it could get its teeth on, including smaller fish, turtles, pterosaurs, and even juvenile mosasaurs. Some estimates suggest it had a top speed close to 60km/hour (37 miles/hour), and given its shape many suspect it could leap out of the water like modern dolphins and may have preyed upon pterosaurs at the surface.

The most famous Xiphactinus fossil tells a cautionary tale about biting off more than you can chew. A number of skeletons have been found with undigested prey in their stomachs, including a thirteen foot long Xiphactinus with a completely preserved, six foot long Gillicus arctuatis in its stomach. The larger fish apparently died soon after eating its prey, most likely due to the smaller fish struggling and rupturing an organ as it was being swallowed.

Ancient Sharks: The Unchanged Predators

The seaway included sharks such as Squalicorax, Cretoxyrhina, and the giant durophagous Ptychodus mortoni believed to be 10 metres (33 ft) long. While mosasaurs and plesiosaurs dominated the headlines, sharks were quietly perfecting their hunting techniques in the ancient seaway.

Cretoxyrhina, known as the “Ginsu shark,” was particularly formidable. Ancient sharks like Squalicorax and Cretoxyrhina were present as apex predators, and scientists have found a large specimen of Cretoxyrhina with Xiphactinus remains in its abdomen. These sharks weren’t just scavengers either.

Like many other species in the Late Cretaceous oceans, a dead or injured individual was likely to be scavenged by sharks. The relationship between these predators was complex, with each species both competing for resources and occasionally dining on one another. It was a classic case of “eat or be eaten” in the ancient seas.

Giant Clams and Strange Mollusks

Paleontologists have dug up the remains of clams six feet in diameter, the largest to ever exist. These weren’t your typical beach clams. Inoceramids (oyster-like bivalve molluscs) were well-adapted to life in the oxygen-poor bottom mud of the seaway, with some like Inoceramus grandis well over a meter in diameter.

The giant clam Inoceramus left common fossilized shells in the Pierre Shale, with thick shells paved with “prisms” of calcite deposited perpendicular to the surface, giving it a pearly luster in life, with paleontologists suggesting the giant size was an adaptation for life in murky bottom waters. Entire schools of fish sometimes sought shelter within the shell of the giant Platyceramus.

Other sea life included invertebrates such as ammonites, squid-like belemnites, and plankton including coccolithophores that secreted the chalky platelets that give the Cretaceous its name. These creatures formed the foundation of the seaway’s food web, supporting the massive predators that dominated the ecosystem.

Flying Reptiles and Ancient Birds

The seaway was home to early birds including the flightless Hesperornis with stout legs for swimming and tiny wings for marine steering, and the tern-like Ichthyornis with a toothy beak, sharing the sky with large pterosaurs such as Nyctosaurus and Pteranodon. The skies above the ancient seaway were just as spectacular as the waters below.

Pteranodon was particularly common. Pteranodon fossils are very common; it was probably a major participant in the surface ecosystem, though it was found in only the southern reaches of the seaway. These flying reptiles had wingspans that could reach over 20 feet, making them formidable aerial predators.

Early birds and Pterosaurs like Nyctosaurus and Pteranodon would have occupied the air currents above the water. The interaction between these aerial hunters and the marine predators below created a complex three-dimensional ecosystem where danger could come from any direction.

The Great Disappearance

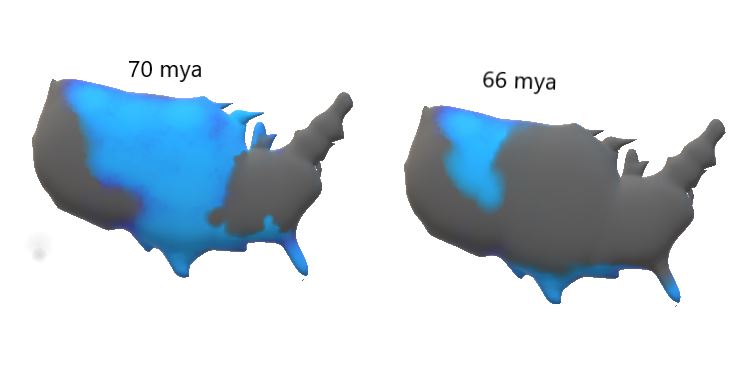

At the end of the Cretaceous, continued Laramide uplift hoisted the sandbanks and muddy brackish lagoons, and the Western Interior Seaway divided across the Dakotas and retreated south towards the Gulf of Mexico, eventually disappearing due to regional uplift and mountain-building. The end of this aquatic paradise wasn’t sudden, but it was inevitable.

The Western Interior Seaway was present during one of the warmest periods on Earth when sea levels were 500 feet higher, but abrupt global cooling likely triggered by a massive asteroid doomed not only the dinosaurs but the ocean as well, with waters dwindling and evaporating over millions of years. The shallow seas regressed towards the end of the Cretaceous, causing a collapse of the mosasaurs’ home territories, and it took the mass extinction at the end of the Cretaceous Period to wipe them out completely.

The Western Interior Seaway’s demise marked the end of an era. Most inhabitants of the Western Interior Seaway perished due to the Cretaceous-Paleogene Extinction Event, a catastrophe that wiped out three-quarters of life on Earth 66 million years ago.

Fossil Treasures Hidden in Plain Sight

In Gove County, Kansas, the Monument Rocks jut magnificently seventy feet up from otherwise flat terrain, made of carbonate rocks which formed on the seafloor over the ocean’s sixty-million-year lifespan, allowing one to almost imagine standing on the prehistoric seabed 2,500 feet below the surface. Today, you can still see evidence of this lost world if you know where to look.

Sometimes regional anoxia led to exceptional preservation of soft tissues, including fossilized remains of cartilaginous sharks, skin impressions of mosasaurs, and completely articulated vertebrate skeletons. Rocks in the south-central U.S. are well-known for bearing fossils from the Western Interior Seaway, particularly the Niobrara Chalk of Kansas, which yields spectacular vertebrates like mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, giant sea turtles, pterosaurs, sharks and other fish, and birds.

Scientists have discovered seawater sealed in what is now North America for 390 million years, opening up a new avenue for understanding how oceans change and adapt with changing climate. These tiny liquid time capsules provide direct evidence of the chemistry of ancient seas, helping scientists piece together the environmental conditions that supported these incredible marine ecosystems.

The lost oceans of North America reveal a world so alien yet so fascinating that it challenges everything we think we know about our continent’s past. From massive marine lizards that could swallow sharks whole to giant clams that housed entire schools of fish, the Western Interior Seaway was home to some of the most spectacular creatures ever to inhabit our planet. These ancient seas remind us that Earth’s history is filled with chapters far more incredible than anything we could imagine, and the fossils they left behind continue to rewrite our understanding of life on our planet. What other secrets might be waiting beneath our feet, hidden in the rocks that once formed the bottom of these magnificent lost oceans?