Imagine a world where entire continents drift beneath the waves, hidden from sight yet holding the keys to understanding Earth’s dynamic past. You’re about to discover how cutting-edge technology is revealing these ghost continents beneath our oceans, rewriting everything scientists thought they knew about our planet’s geology. From ancient landmasses that once thrived above sea level to mysterious plate fragments buried deep in Earth’s mantle, these underwater discoveries are fundamentally changing how you see the world beneath your feet.

Recent advances in sonar mapping and seismic imaging have uncovered a stunning truth: the ocean floors conceal far more continental material than anyone imagined. These features include plateaus and mountains made of continental crust hidden below sea level, including Zealandia extending underwater from New Zealand and several smaller microcontinents discovered in the Indian Ocean. You might wonder how entire continents can simply disappear beneath the waves, yet this phenomenon is reshaping our understanding of Earth’s geological history.

So let’s dive into this extraordinary underwater world where modern technology meets ancient mysteries.

The Hidden Microcontinent of Mauritia

Deep beneath the turquoise waters of the Indian Ocean lies one of the most remarkable geological discoveries of recent decades. Scientists have identified remnants of a landmass dubbed Mauritia, which split from Madagascar when tectonic rifting sent the Indian subcontinent surging northeast millions of years ago, with subsequent stretching sinking the fragments that together comprised an island about three times the size of Crete. This continent fragment detached about 60 million years ago while Madagascar and India drifted apart, hidden under huge masses of lava.

You’ll find the evidence for Mauritia scattered across the beaches of modern-day Mauritius island in the form of ancient zircon crystals. These zircons, dated between 2.5 billion and 3 billion years old, were found within far younger volcanic rocks on an island thought to have formed only 8 million years ago, suggesting the zircons formed on a much older landmass. Through process of elimination, scientists concluded these zircons were brought up from the ocean floor when lava erupted to the surface, snatching fragments of ancient continental crust buried on the seafloor.

Revolutionary Sonar Technology Unveiling Ocean Secrets

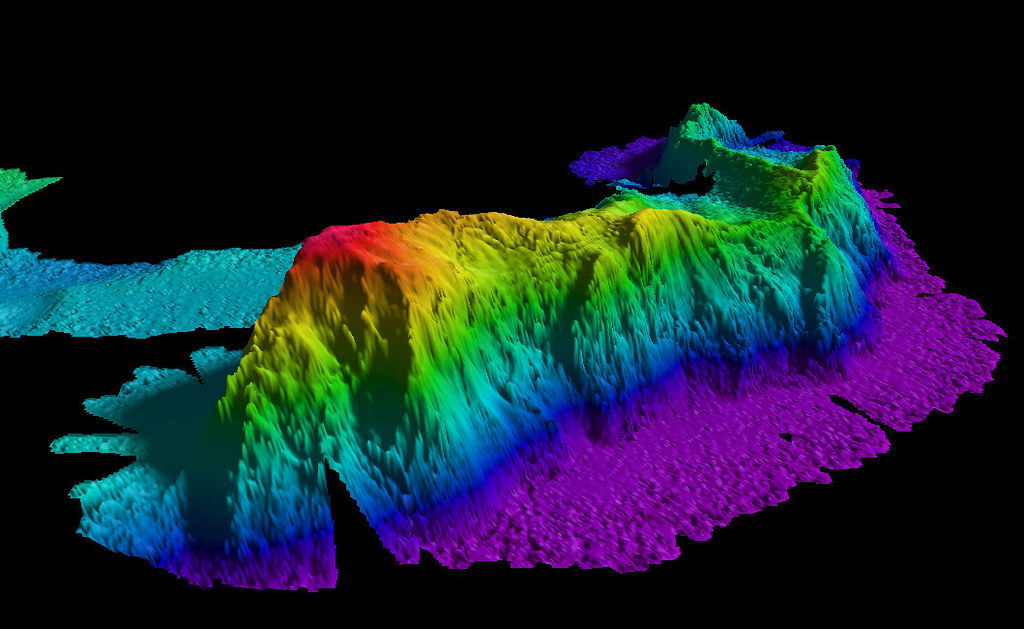

Modern multibeam sonar systems like the EM300 send out 30 kHz acoustic energy in beams that produce a fanned arc of up to up to 432 individual beams, each as narrow as one degree, creating swaths up to 5000 meters wide depending on water depth. With about 1500 sonar soundings sent out per second, multibeam systems paint the seafloor in a fanlike pattern, creating detailed sound maps that show ocean depth, bottom type, and topographic features.

The technology has evolved dramatically from Marie Tharp’s pioneering work in the 1950s. Using thousands of files of sonar readings from U.S. Navy ships, she mapped data showing a huge north-to-south mountain range underneath the Atlantic Ocean, bordered by a rift valley. Today’s sophisticated systems can detect features with millimeter precision, allowing scientists to distinguish between massive submarine volcanoes and genuine continental fragments hidden beneath layers of sediment.

Zealandia: Earth’s Eighth Continent Revealed

New Zealand has a total land area of 268,000 square kilometers, but Zealandia, the proposed continent, covers 4,920,000 square kilometers, about three-fifths the size of Australia. Though 94% of Zealandia is covered by the Pacific Ocean, bathymetric maps and geological features make the proposal for continental status more convincing. Zealandia meets the definitions of a continent as a continuous expanse of continental crust, linked by islands from New Caledonia to the north, through New Zealand’s islands, to the Auckland Islands and Campbell Island to the south.

The discovery of Zealandia demonstrates how much continental material remains hidden beneath the waves. While the geology of New Zealand and New Caledonia has been known for some time, only recently has their common heritage as part of a much larger continent been accepted. This recognition fundamentally challenges traditional definitions of what constitutes a continent.

Seismic Discoveries in Earth’s Deep Mantle

Scientists applying full-waveform inversion to the lower mantle found pockets that appear to be leftover plate fragments in areas with no known history of subduction, and were startled by how common these hidden anomalies seemed to be. One of the biggest surprises was in a zone under the western Pacific, where according to current plate tectonic timelines, there’s no reason for old plate fragments to be there, with such zones apparently much more widespread than previously thought.

The study identified numerous high-velocity anomalies throughout Earth’s mantle that previous studies had missed, with the most significant discovery being the large anomaly beneath the western Pacific Ocean at depths between 900-1200 kilometers, unlike previously detected anomalies which typically correlate with known subduction zones. Some scientists suggest these may be ancient, silica-rich pockets left over from the early mantle, indicating a more diverse range of compositions in Earth’s mantle than previously understood.

Advanced Mapping Technologies From Space

NASA’s SWOT satellite collaboration recently published one of the most detailed maps of the ocean floor, though only about 25% has been surveyed directly by ship-based sonar, with researchers relying on satellite data to produce a global picture of the seafloor. Using a year’s worth of SWOT data, scientists focused on seamounts and underwater continental margins, with previous satellites detecting massive seamounts over 3,300 feet tall, while SWOT can pick up seamounts less than half that height, potentially increasing known seamounts from 44,000 to 100,000.

These satellite technologies complement ambitious projects like Seabed 2030. An international team launched the first effort to create a comprehensive map of the world’s oceans using recent advances in sonar technology, with the goal of mapping the entire seafloor in high resolution by 2030. The challenge is immense considering that there are better maps of the Moon’s surface than of the bottom of Earth’s ocean, with researchers working for decades to change that.

Continental Fragments Hidden Beneath Volcanic Activity

The break-up of continents is often associated with mantle plumes, giant bubbles of hot rock that rise from the deep mantle and soften tectonic plates until they break apart, as happened when Eastern Gondwana broke apart about 170 million years ago, fragmenting into Madagascar, India, Australia and Antarctica. When the rupture zone lies at the edge of a landmass, fragments may be separated off, with the Seychelles being a well-known example, while geoscientists have now published studies suggesting the existence of further fragments based on lava sand grains from Mauritius beaches.

What was previously interpreted only as the trail of the Reunion hotspot are actually continental fragments not previously recognized because they were covered by volcanic rocks of the Reunion plume, suggesting that microcontinents in the ocean occur more frequently than previously thought. This discovery highlights how volcanic activity can effectively camouflage entire continental fragments, making them nearly impossible to detect without sophisticated analysis.

Ancient Plate Fragments and the Pontus Discovery

Scientists discovered a long-lost tectonic plate dubbed “Pontus” that was once a quarter of the size of the Pacific Ocean, known only from rock fragments in Borneo’s mountains and ghostly remnants of its huge slab detected deep in Earth’s mantle. Sometimes rocks from a lost plate get incorporated into mountain-building events, and these remnants can point to the location and formation of ancient plates, as researchers attempted to find while doing fieldwork in Borneo.

Using computer models to investigate the region’s geology over the last 160 million years, the plate reconstruction showed a hiccup between what is now South China and Borneo, where an ocean once thought to be underpinned by the Izanagi plate actually wasn’t, with the Borneo rocks fitting into that mystery gap. The researchers discovered this spot was occupied by a never-before-known plate named the Pontus plate, which formed at least 160 million years ago but was probably far older.

The Future of Ocean Floor Exploration

The more scientists explore and sample the ocean depths, the more likely they’ll discover additional lost continents. The only foolproof way to distinguish between massive submarine volcanoes and lost continents is collecting rock samples from the deep ocean, though much of the seafloor is covered in soft sediment that obscures solid rock, requiring sophisticated mapping systems to search for steep slopes more likely to be free of sediment before sending metal rock-collecting buckets to grab samples.

The future of seafloor mapping looks hopeful thanks to new technologies and increased collaboration, with organizations like the Schmidt Ocean Institute pledging to share all mapping data, while new autonomous vessels are mapping the seafloor more efficiently than crewed vessels, as demonstrated by a SEA-KIT vessel that mapped over 350 square miles remotely controlled from Essex, England. These technological advances promise to accelerate discoveries exponentially.

These ghost continents represent more than just geological curiosities buried beneath the waves. They fundamentally challenge how you understand Earth’s dynamic history and the very definition of continents themselves. From Mauritia’s ancient zircon crystals to Zealandia’s vast underwater expanse, these discoveries reveal that our planet’s surface is far more complex and interconnected than previously imagined. As sonar technology continues advancing and more researchers explore the deep ocean, expect many more surprises lurking in the darkness below. What other secrets might be waiting to reshape our understanding of Earth’s hidden landscapes?