Picture yourself diving into the ancient oceans of the Early Jurassic, around 180 million years ago. Instead of modern whales breaching the surface, you’d witness something far more extraordinary. Massive marine reptiles with bodies like dolphins but sporting dinner plate-sized eyes glided through these primordial waters with deadly grace. These were the ichthyosaurs, and recent scientific discoveries have revealed them to be nature’s original stealth hunters.

Recent breakthroughs in fossil analysis have completely revolutionized our understanding of these ancient predators. Far from being simple marine reptiles, they possessed sophisticated adaptations that allowed them to hunt with an almost supernatural silence. Let’s explore the incredible world of these Jurassic assassins and discover how they mastered the art of underwater stealth long before any modern predator.

Origins of the Ocean’s Most Successful Predators

Ichthyosaurs first appeared around 250 million years ago during the Triassic period and survived for roughly 160 million years until the Late Cretaceous. Think about that for a moment. These creatures dominated Earth’s oceans for longer than dinosaurs ruled the land. They evolved from land reptiles that returned to the sea, similar to how modern whales evolved from terrestrial mammals, swimming with lateral undulations of the tail and steering with elongate fore paddles.

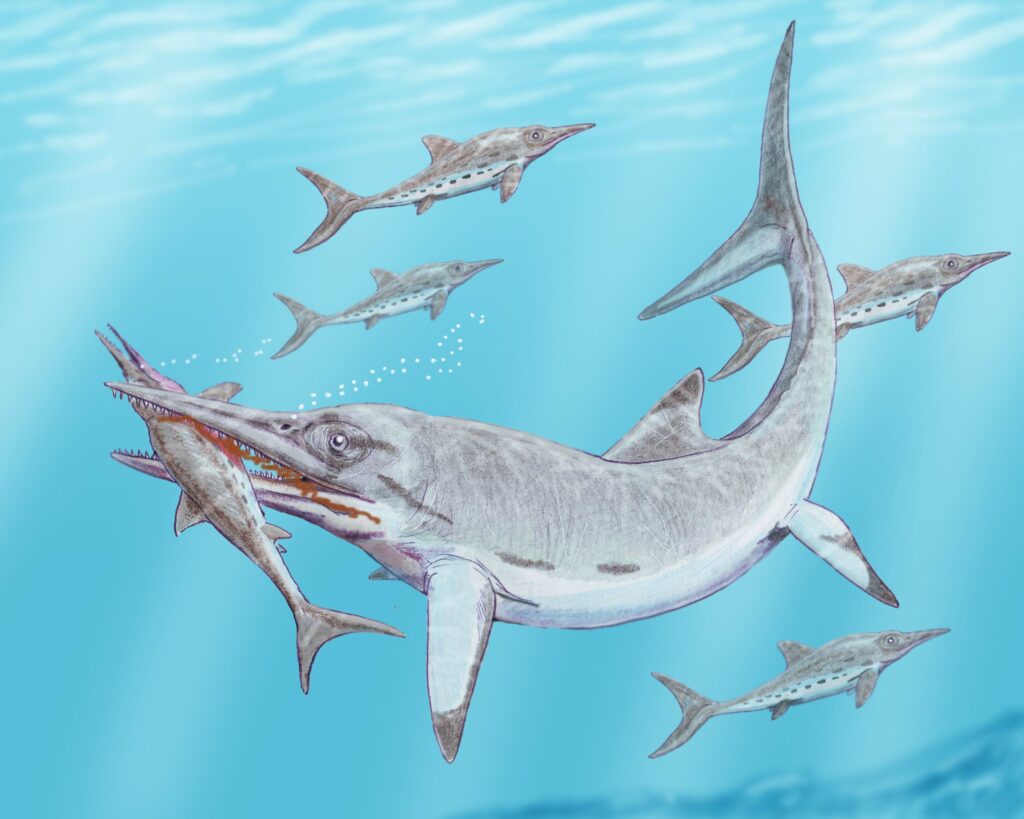

Ichthyosaurs reached their peak diversity during the Early Jurassic, with an array of morphologies including huge apex predators like Temnodontosaurus and swordfish-like Eurhinosaurus. These marine reptiles evolved streamlined, fish-like bodies for fast swimming and lived in waters that covered much of continental Europe during the early Jurassic Period. Their success was so remarkable that they occupied virtually every marine ecological niche imaginable.

The Apex Predator That Redefined Ocean Warfare

Among all ichthyosaurs, one genus stood supreme as the ultimate marine assassin. Temnodontosaurus was a giant ichthyosaur that dominated the Early , growing to exceed 12 meters (30 feet) in length. This large Early Jurassic neoichthyosaurian was the only post-Triassic ichthyosaurian known with teeth bearing distinct cutting edges or carinae.

Temnodontosaurus was an apex predator, likely consuming fish, plesiosaurs, ichthyosaurs and cephalopods, being the only Jurassic ichthyosaur with a main diet of vertebrates. Fossils prove that this fierce sea dragon fed on smaller ichthyosaurs. Its name literally means “cutting-tooth lizard,” and for good reason. Temnodontosaurus’ jaws were slim and lined with barbed teeth, making it a formidable predator capable of tackling prey its own size.

Eyes Like Footballs: The Ultimate Visual Hunters

Perhaps the most striking feature of these ancient predators was their enormous eyes. Temnodontosaurus had the largest eyes of any ichthyosaur, and among the largest of any animal. With eyes the size of footballs, this monster was able to hunt at all depths of the Jurassic ocean, growing up to 33 feet long.

Temnodontosaurus, with eyes that had a diameter of twenty-five centimetres, could probably still see at a depth of 1,600 metres, where such eyes would have been especially useful to see large objects. Temnodontosaurus’ eyes bore sclerotic rings, which provided rigidity and structure for its eyes when descending into the deep depths of the ocean, with T. platyodon’s sclerotic rings being about 25 centimeters long in diameter. These massive visual organs were perfectly adapted for hunting in the dimly lit depths where most prey couldn’t detect their approach.

The Revolutionary Discovery: Stealth Technology in Ancient Seas

In 2009, a fossil collector made a discovery that would completely change our understanding of ichthyosaur hunting strategies. The fossilized flipper was discovered by fossil collector Georg Göltz entirely by chance whilst looking for fossils at a temporary exposure at a road cutting in the municipality of Dotternhausen, Germany. A controlled blast sprung a layer of limestone loose from shale, and scattered chunks of rock bearing a detailed impression of an ichthyosaur fin across the site, with the fossil collector gathering all the pieces he could.

This discovery revealed a metre-long front flipper of the large-bodied Jurassic ichthyosaur Temnodontosaurus, including unique details of its soft-tissue anatomy, preserving a serrated trailing edge that is reinforced by novel cartilaginous integumental elements. Having examined thousands of ichthyosaurs, paleontologist Dean Lomax had never seen anything quite like it. This single fossil would revolutionize our understanding of prehistoric marine predation.

Silent Swimming: The Acoustic Stealth System

The most remarkable aspect of this discovery wasn’t just the preservation, but what it revealed about ichthyosaur hunting behavior. A new study has uncovered evidence that a giant marine reptile from the Early Jurassic period used stealth to hunt its prey in deep or dark waters – much like owls on land today. The wing-like shape of the flipper, together with the lack of bones in the distal end and distinctly serrated trailing edge collectively indicate that this massive animal had evolved means to minimize sound production during swimming, moving almost silently through the water similar to how living owls fly quietly when hunting at night.

Both the surface ridges and edge serrations showed promise for minimizing noise, especially for the low frequencies that travel farthest under water, with the modeled sound reduction being as high as 10 decibels. Computer simulations of the fluid dynamics showed that the serrated edge of the flipper provided the ancient marine reptile with stealth by suppressing hydrodynamic noise caused by the flipper. This was underwater stealth technology that wouldn’t be matched in nature for millions of years.

Anatomical Innovations: Engineering Perfect Silence

The fossil revealed several unique anatomical features that enabled this stealth capability. The fin’s proportions were unique – especially long and thin, with the end of the fin lacking bones, leaving a soft, flexible tip not seen in other known living or extinct animal examples, and evenly spaced lines running over the entire surface with distinct serrations on the trailing edge. X-ray microscopy showed these serrations were composed entirely of cartilage embedded in skin.

The fleshy tip of the flipper didn’t have any bones – it contained only cartilage, which would have helped the animal move more efficiently, kind of like the upward-pointing winglets on the tips of commercial airplane wings. Through subtle posterior flexions, the ichthyosaur could execute precise lateral movements without generating telltale hydrodynamic or acoustic signals, with the fleshy tips featuring passive flow control cues that helped negate pressure fluctuations and minimize turbulent wakes. Nature had engineered the perfect silent propulsion system.

Sensory Superpowers: Beyond Just Vision

The stealth adaptations extended beyond simple noise reduction. Based on ultrastructural similarities between fossilized ‘pores’ and scale organs of extant reptiles, it’s possible that they possessed cutaneous receptors to sense water-borne mechanical stimuli. The sensory systems of Temnodontosaurus may have extended beyond vision and hydrodynamic stealth, with fossilized ultrastructural ‘pores’ bearing strong resemblance to scale organs in extant reptiles known for mechanoreception.

These unique ichthyosaurs possessed fossilized ultrastructural ‘pores’ that bear strong resemblance to scale organs in extant reptiles known for mechanoreception, suggesting they possessed cutaneous receptors capable of sensing water-borne stimuli, enhancing spatial awareness in murky or low-light aquatic environments, with low-frequency sound detection probably well within their sensory repertoire. They were essentially living underwater sensor arrays, detecting the slightest movements and vibrations in the water column around them.

Evolutionary Arms Race: Predator versus Prey

To be useful for a hunting ichthyosaur, sound dampening should be within the detectable frequency range of its intended prey, and besides other ichthyosaurs, coleoid cephalopods are known from Temnodontosaurus bromalites, and they are sensitive to low-frequency sounds. Comparative evidence points to a coevolutionary interplay between Jurassic parvipelvian ichthyosaurs and their prey, wherein increasing predator stealth selected for improved visual sensitivity and reduced noise generation, while prey species such as coleoid cephalopods developed enhanced sensitivity to hydrodynamic and acoustic cues.

Fossil evidence of coleoid remains alongside ichthyosaur specimens suggests these stealth adaptations enabled close approaches without triggering escape behaviors in agile and acoustically sensitive invertebrates. The ancient seas were a theater of evolutionary warfare, with predators and prey locked in an endless cycle of adaptation and counter-adaptation. The ichthyosaurs had clearly won this particular battle, at least for their time.

Legacy and Modern Implications

The discovery of ichthyosaur stealth technology has implications that extend far beyond paleontology. Scientists noted that because human-induced noise from shipping activity, military sonar, seismic surveys, and offshore wind farms has a negative impact on today’s aquatic life, these findings could provide inspiration to help limit the adverse biological effects from anthropogenic input to the modern marine soundscape. Paleontologists propose that modern ships could employ a similar system used by ancient marine reptiles, with researchers currently exploring the effectiveness of passive flow control devices, such as trailing edge serrations and surface treatments, showing that such features already existed in ichthyosaurs 183 million years ago.

The fossil provides new information on flipper soft tissues, has structures never seen in any animal, reveals a unique hunting strategy, and its noise-reducing features may even help reduce human-made noise pollution, representing what some consider one of the greatest fossil discoveries ever made. The ancient seas continue to teach us lessons about engineering, biology, and environmental stewardship that remain startlingly relevant in our modern world.

These silent assassins of the mastered stealth hunting techniques that modern technology is only beginning to understand and replicate. Their legacy lives on not just in the fossil record, but in the innovative solutions they provide for contemporary challenges. What other secrets might these ancient predators still be hiding in the depths of geological time? The ocean’s greatest hunters may have vanished millions of years ago, but their evolutionary innovations continue to inspire and amaze us today.