Picture these massive woolly beasts roaming across frozen steppes for hundreds of thousands of years, surviving ice ages and climate fluctuations that would make today’s changes seem mild. Yet by roughly four thousand years ago, the last mammoth had drawn its final breath on a remote Arctic island.

This enduring mystery has sparked fierce scientific debates for over a century. Were our ancestors responsible for driving these magnificent creatures to extinction through relentless hunting, or did natural climate shifts deliver the fatal blow? Recent groundbreaking research using ancient DNA and sophisticated climate modeling is finally revealing the truth behind one of prehistory’s most puzzling disappearances.

The Great Ice Age Empire

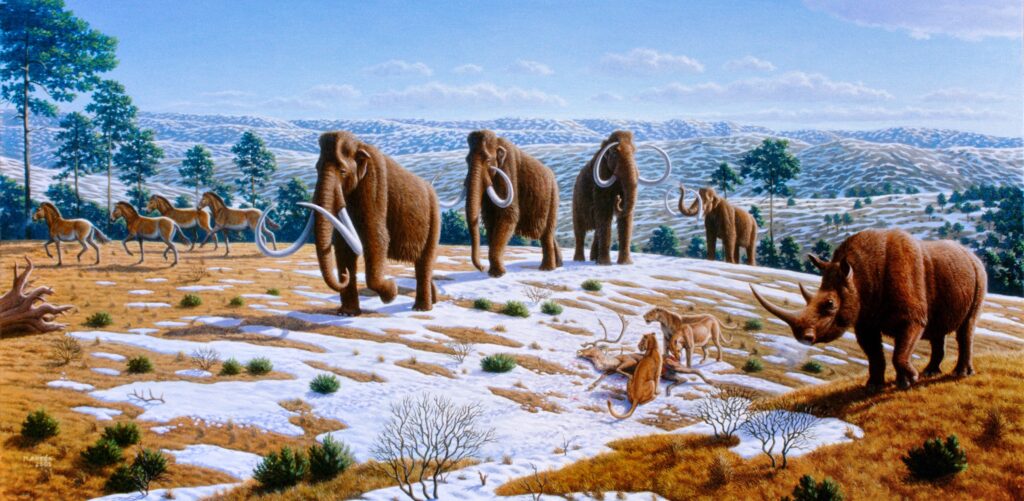

Woolly mammoths inhabited Eurasia and North America from late Middle Pleistocene (300,000 years before present), surviving through different climatic cycles until they vanished in the Holocene, with the last populations on mainland Siberia persisting until around 10,000 years ago, although isolated populations survived on St. Paul Island until 5,600 years ago and on Wrangel Island until 4,000 years ago. These weren’t just scattered herds struggling to survive. This ecosystem covered wide areas of the northern part of the globe, thrived for approximately 100,000 years without major changes, with mammoth steppe being Earth’s most extensive biome that spanned from Spain to Canada and from arctic islands to China.

The vegetation was dominated by palatable, high-productivity grasses, herbs and willow shrubs, and the fauna was dominated by species such as reindeer, muskox, saiga antelope, steppe bison, horses, woolly rhinoceros and woolly mammoth. Think of it like the African savanna, but covered in snow. Animal biomass in mammoth steppe was as high as in African savannah.

When the World Warmed Up

Scientists found that it was not just the climate changing that was the problem, but the speed of it that was the final nail in the coffin, as they were not able to adapt quickly enough when the landscape dramatically transformed and their food became scarce, with climate warming causing trees and wetland plants to take over and replace the mammoth’s grassland habitats. Suitable climate conditions for the mammoth reduced drastically between the Late Pleistocene and the Holocene, with 90% of its geographical range disappearing between 42,000 and 6,000 years ago, with the remaining suitable areas being mainly restricted to Arctic Siberia.

At the beginning of the Holocene, mossy forests, tundra, lakes and wetlands displaced mammoth steppe, as the cold dry climate switched to a warmer wetter climate that caused the disappearance of the grasslands and their dependent megafauna. Picture vast productive grasslands slowly transforming into soggy tundra and thick forests. This finding indicates that the wetter Holocene climate allowed marshes, lakes, and forest to encroach on steppe vegetation, leaving large herbivores like mammoths without a suitable habitat.

Humans Enter the Picture

The woolly mammoth coexisted with early humans, who hunted the species for food, and used its bones and tusks for making art, tools, and dwellings. The hairy cousins of today’s elephants lived alongside early humans and were a regular staple of their diet, with their skeletons used to build shelters, harpoons carved from their giant tusks, artwork featuring them daubed on cave walls, and the oldest known musical instrument made from a mammoth bone. However, the relationship between humans and mammoths appears more complex than simple predator and prey.

A site near the Yana River in Siberia revealed several specimens with evidence of human hunting, but the finds were interpreted to show that the animals were not hunted intensively, but perhaps mainly when ivory was needed, while two woolly mammoths from Wisconsin show evidence of having been butchered by Paleo-Indians. Many archaeologists and paleontologists argue that human hunting makes little sense as a cause for the extinction, because few kill sites, where large fauna were butchered, exist in the archaeological record.

The Deadly Combination Theory

Results of population models show that the collapse of the climatic niche of the mammoth caused a significant drop in their population size, making woolly mammoths more vulnerable to the increasing hunting pressure from human populations, with the coincidence of the disappearance of climatically suitable areas and the increase in anthropogenic impacts in the Holocene likely setting the place and time for the woolly mammoth’s extinction. This wasn’t a case of either climate change or humans acting alone.

It seems that, in the case of the mammoth, it was the climate that forced the species to the point of extinction, and it was mankind that gave the woolly beast the last shove into oblivion. For optimistic parameters, one woolly mammoth killed every three years by each human being inhabiting its distribution range would be sufficient to lead the species to extinction, while with a low density and suboptimal woolly mammoth population, one mammoth killed by each person every 200 years would suffice. The mathematics are stark and revealing.

Different Regions, Different Stories

The dynamics of different woolly mammoth populations varied as they experienced very different magnitudes of climatic and human impacts over time, suggesting that extinction causes would have varied by population, with most populations disappearing between 14,000 and 10,000 years ago. During the Younger Dryas age, woolly mammoths briefly expanded into north-east Europe, whereafter the mainland populations became extinct, with woolly mammoths confined to the northernmost regions of Siberia due to the warming induced expansion of unfavourable wet tundra and forest environments.

The woolly mammoths of eastern Beringia (modern Alaska and Yukon) had died out about 13,300 years ago, soon after the first appearance of humans in the area, which parallels the fate of all the other late Pleistocene proboscideans. Meanwhile, some populations managed to hold on longer in different circumstances. The St. Paul Island mammoth population apparently died out significantly before human arrival. This suggests local factors played crucial roles beyond the global climate trends.

The Last Survivors on Wrangel Island

Roughly 10,000 years ago, a small group of woolly mammoths found themselves stuck on an island off the coast of Siberia, while their mainland peers disappeared, this isolated herd multiplied, as around 15,000 years ago, these behemoth creatures began to vanish because of human hunting and habitat loss due to natural climate changes until all that remained were a few small herds living on islands, with one group ending up on Wrangel Island, a landmass about the size of Delaware that got cut off from mainland Siberia by rising sea levels.

Wrangel Island had no predators including humans and no other grazing animals, which gave the woolly mammoths carte blanche to munch and reproduce freely, with the colony ballooning from eight breeding individuals to between 200 and 300 mammoths within just 20 generations. They became the only surviving members of their species and thrived for around 6,000 years until they, too, died out. Based on results, the extinction must have happened rapidly. What killed these final survivors remains one of paleontology’s enduring puzzles.

Rapid Climate Oscillations: The Smoking Gun

A new study concludes that abrupt changes in the climate played a key role in these giant species vanishing around 11,000 years ago, with an international team finding that short, rapid warming events, known as interstadials, recorded during the last ice age coincided with major extinction events. They found the warming events continued over thousands of years, with temperatures spiking up 7.2 to 28 degrees Fahrenheit, with the temperature spikes appearing to be staggered over time, possibly due to some events being regional in nature.

It now looks as though rapid warming at the end of the ice age, not the frigid cold of the ice age itself, was largely responsible for the megafauna extinction, with a team of geneticists reporting that DNA evidence from the late Pleistocene shows the major turnover of species lines up perfectly with a period of sudden climate oscillations identified in ice cores. The abrupt warming of the climate caused massive changes to the environment that set the extinction events in motion, but the rise of humans applied the coup de grace to a population that was already under stress.

Modern Lessons from Ancient Extinctions

This is a stark lesson from history and shows how unpredictable climate change is, as once something is lost, there is no going back, with precipitation being the cause of the extinction of woolly mammoths through changes to plants, as the change happened so quickly that they could not adapt and evolve to survive. It shows nothing is guaranteed when it comes to the impact of dramatic changes in the weather, as the early humans would have seen the world change beyond all recognition, which could easily happen again and we cannot take for granted that we will even be around to witness it, with the only thing we can predict with any certainty being that the change will be massive.

Although the debate about the fate of the mammoth steppe and the definitive cause of megafauna’s extinction is not over, this research definitely added some very robust evidence to support that climate change was the driver for the last late Quaternary extinction. We have shown that climate change, specifically precipitation, directly drives the change in the vegetation, with humans having no impact on them at all based on our models. The evidence continues mounting that while humans played a supporting role, climate change was the primary director of this prehistoric tragedy.

What do you think drove the mammoths to extinction? The evidence points to a complex interplay where climate change weakened these ancient giants, making them vulnerable to the final push from human activities. This sobering reminder from our planet’s past shows how quickly dominant species can vanish when faced with rapid environmental change.