The prehistoric skies were once dominated by creatures that would astound us today – magnificent flying reptiles that soared above dinosaurs, with wingspans rivaling small aircraft. Among these aerial giants, Quetzalcoatlus and Pteranodon stand out as iconic representatives of the pterosaur lineage. Though often confused in popular media, these two pterosaurs differed dramatically in size, anatomy, lifestyle, and evolutionary timing. This comparison explores the fascinating distinctions and similarities between these remarkable flying reptiles that conquered ancient skies millions of years before the first birds took flight.

The Pterosaur Family Tree: Where They Fit

Pterosaurs represented the first vertebrates to evolve powered flight, predating birds by over 70 million years and bats by about 150 million years. Both Quetzalcoatlus and Pteranodon belonged to this diverse group of flying reptiles that lived from the late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous period (228-66 million years ago). While they share the pterosaur classification, they belonged to different families within the order. Pteranodon was a pteranodontid, a family characterized by its large size and distinct cranial crests, evolving during the Late Cretaceous. Quetzalcoatlus, meanwhile, belonged to the more advanced azhdarchid family, representing some of the last and largest pterosaurs that ever lived. Their positioning on the pterosaur family tree reflects millions of years of evolutionary divergence, resulting in their distinct characteristics despite their superficial similarities as flying reptiles.

Quetzalcoatlus: The Ground-Dwelling Giant

Named after the Aztec feathered serpent god Quetzalcoatl, Quetzalcoatlus northropi stands as potentially the largest flying animal ever to exist. This azhdarchid pterosaur lived during the Late Cretaceous period, approximately 68-66 million years ago, in what is now North America. With an estimated wingspan ranging from 10-11 meters (33-36 feet) and standing as tall as a giraffe when on the ground (about 5-6 meters or 16-20 feet), Quetzalcoatlus was truly a colossus of the skies. Unlike earlier pterosaurs, fossil evidence suggests Quetzalcoatlus was well-adapted for terrestrial locomotion, walking efficiently on all fours with its wings folded. This massive pterosaur had a proportionally small body compared to its enormous wings, with a distinctively long neck and elongated, toothless beak that made it perfectly adapted for its specialized lifestyle as a ground-feeding predator in inland environments.

Pteranodon: The Ocean-Soaring Specialist

Pteranodon, whose name aptly means “wing without tooth,” lived approximately 86-84.5 million years ago during the Late Cretaceous period across what is now North America, particularly in the Western Interior Seaway that once divided the continent. With a wingspan reaching about 7 meters (23 feet) in the largest specimens, Pteranodon was impressive but substantially smaller than Quetzalcoatlus. Their most distinctive feature was the dramatic backward-pointing cranial crest, which was significantly larger in males, suggesting its use in sexual display rather than aerodynamics. Unlike the ground-adapted Quetzalcoatlus, Pteranodon was built for extended oceanic soaring, with proportionally longer wings relative to its body size and features suggesting it spent much of its life gliding over open waters. Fossil evidence consistently places Pteranodon in marine environments, indicating it was a specialized fish-eater that likely caught prey by skimming over water surfaces, similar to modern seabirds.

Size Comparison: The True Sky Giants

The size difference between these pterosaurs was substantial and reflects their divergent evolutionary paths. Quetzalcoatlus represents one of aviation’s ultimate achievements, with the largest specimens estimated to have wingspans of 10-11 meters (33-36 feet) and a weight of around 200-250 kilograms (440-550 pounds) – dimensions approaching the size of a small aircraft. Standing upright, it would have towered over humans at approximately the height of a giraffe. Pteranodon, while still enormous by modern standards, was considerably smaller, with a maximum wingspan of about 7 meters (23 feet) and weighing an estimated 20-25 kilograms (44-55 pounds). These size differences weren’t merely matters of scale but reflected fundamental differences in their ecological niches and lifestyles. Quetzalcoatlus achieved the theoretical maximum size possible for a flying animal given the Earth’s gravity and atmosphere, with some researchers suggesting larger specimens may have been at the very limits of powered flight capability.

Cranial Adaptations and Feeding Styles

The skull structures of these pterosaurs reveal dramatic differences in feeding ecology and lifestyle. Pteranodon had a relatively long, narrow beak with no teeth, ending in a sharp point that was ideally suited for grasping slippery fish. Their skull featured the famous backward-projecting cranial crest that could reach over 1.8 meters (6 feet) in large males, but was much smaller in females, representing one of prehistory’s most striking examples of sexual dimorphism. Quetzalcoatlus, by contrast, had an exceptionally long, straight beak relative to its head size, also lacking teeth but built for a completely different feeding strategy. Its massive skull could reach 3 meters (10 feet) in length, with a deep lower jaw and reinforced construction suggesting tremendous strength. Fossil evidence and anatomical studies indicate that Quetzalcoatlus was likely a terrestrial stalker that used its beak to probe for small animals, carrion, and possibly even dinosaur eggs, functioning more like a stork or ground hornbill than the fish-hunting Pteranodon.

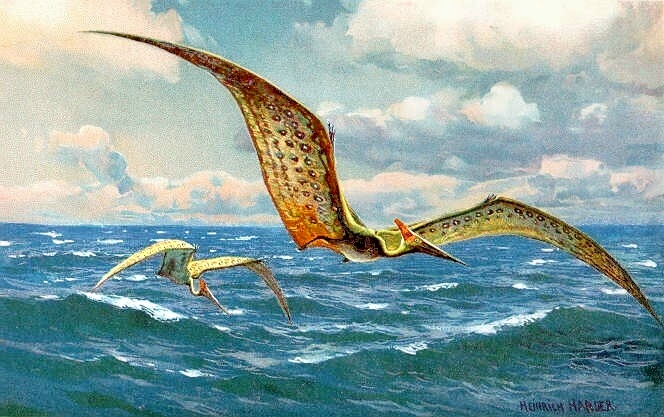

Flight Mechanics and Aerial Abilities

Despite both being accomplished flyers, Quetzalcoatlus and Pteranodon exhibited significantly different flight adaptations. Pteranodon was built for efficient soaring over vast oceanic expanses, with long, narrow wings optimized for gliding on thermal currents with minimal energy expenditure. Its wing proportions suggest it was similar to modern albatrosses, capable of staying aloft for extended periods while covering great distances in search of food. Quetzalcoatlus presents a more complex flight profile – its massive size pushed the theoretical limits of powered flight. Biomechanical studies suggest it likely needed strong downstrokes to become airborne, possibly launching itself with powerful hind limbs in a quadrupedal leap. Once airborne, it would have been capable of soaring efficiently, using thermal currents to travel long distances with minimal energy, though its immense size would have made it less maneuverable than smaller pterosaurs. Some researchers hypothesize that the largest specimens may have been primarily terrestrial as adults, only flying occasionally or when necessary.

Habitat and Geographical Distribution

The habitats these creatures dominated were as different as their physical adaptations. Pteranodon fossils are consistently found in marine deposits associated with the Western Interior Seaway, a vast inland sea that divided North America during the Late Cretaceous period. This distribution, along with their anatomy, strongly indicates they were specialized for a pelagic (open ocean) lifestyle, rarely venturing far inland. Stomach contents containing fish remains further confirm their marine ecological niche. Quetzalcoatlus fossils, in contrast, are primarily found in inland, terrestrial deposits, particularly in Texas and surrounding regions that would have been well removed from coastlines during the Late Cretaceous. This distribution aligns with anatomical features, suggesting adaptation to terrestrial environments with varied terrain. The geographical separation of these pterosaurs reflects how pterosaur lineages evolved to exploit different ecological niches, with minimal competition between these distantly related species that occupied separate habitats and geographical regions during their respective periods.

Evolutionary Timing and Coexistence

Despite often being depicted together in popular media, Quetzalcoatlus and Pteranodon were separated by millions of years and never shared the skies. Pteranodon lived approximately 86-84.5 million years ago during the middle of the Late Cretaceous period, while Quetzalcoatlus appeared much later, thriving during the very end of the Cretaceous period around 68-66 million years ago, right up until the mass extinction event that eliminated the non-avian dinosaurs. This significant temporal separation reflects their positions on the pterosaur evolutionary timeline, with Pteranodon representing an earlier specialized branch and Quetzalcoatlus emerging from the later azhdarchid radiation. This timing is crucial for understanding pterosaur evolution, as it shows how flying reptiles continued to diversify and adapt to new niches even in the final stages of the Mesozoic Era. The late appearance of giants like Quetzalcoatlus demonstrates that pterosaurs were still evolving new forms and reaching size extremes right before their extinction, rather than gradually declining as was once thought.

Locomotion on Land: Grounded Differences

How these pterosaurs moved when not in flight reveals another stark contrast in their lifestyles. Quetzalcoatlus shows anatomical adaptations suggesting it was highly competent on land, with sturdy limb bones and features indicating it could walk efficiently using a quadrupedal stance, with the wing fingers pointed outward and upward. This terrestrial proficiency aligns with theories that it hunted like modern ground birds, stalking prey across open landscapes. Track evidence of related azhdarchids shows they could walk with surprising efficiency, contradicting older notions that pterosaurs were awkward on land. Pteranodon, conversely, appears to have been much less adapted for terrestrial locomotion, with limb proportions suggesting limited ground mobility. Its foot structure and leg anatomy indicate it would have been comparatively clumsy on land, likely spending minimal time grounded except for breeding purposes. This difference in terrestrial capability perfectly complements their different feeding strategies – the fish-hunting Pteranodon needed only to land occasionally, while Quetzalcoatlus’ hunting style required substantial time walking and stalking prey on the ground.

Hunting and Dietary Adaptations

Dietary specializations drove many of the anatomical differences between these pterosaurs. Pteranodon’s feeding strategy is well-established based on its oceanic habitat, narrow skull morphology, and occasional fish remains associated with its fossils. Like modern gannets or pelicans, it likely flew over water bodies, spotting fish from above before making precise dives or surface dips to capture prey. Its long, pointed beak was perfectly adapted for seizing slippery fish, while its toothless jaws suggest it swallowed prey whole rather than processing it extensively. Quetzalcoatlus presents a more complex and debated feeding ecology. Its ground-dwelling adaptations and long neck suggest it was likely a terrestrial stalker that preyed upon small animals, including lizards, mammals, and juvenile dinosaurs. Some researchers propose it may have probed into soil or shallow water for invertebrates, similar to modern storks, while others suggest it could have scavenged from dinosaur carcasses. This diversity of potential food sources would have made Quetzalcoatlus more adaptable to environmental changes, though specialized enough to dominate its terrestrial niche.

Reproduction and Life History

While direct evidence of reproductive behavior remains limited for both genera, pterosaur reproduction can be inferred from related species and comparative anatomy. Like all pterosaurs, both Quetzalcoatlus and Pteranodon laid eggs rather than giving birth to live young, with recent fossil discoveries confirming pterosaurs produced parchment-shelled eggs similar to many modern reptiles. Sexual dimorphism was pronounced in Pteranodon, with males possessing dramatically larger head crests and generally larger body sizes, suggesting complex mating displays and possible harem-based social structures. For Quetzalcoatlus, sexual dimorphism remains less clearly established due to fewer specimens, though size variations hint at similar patterns. Both pterosaurs likely produced relatively small clutches of eggs compared to their body size, following the pattern seen in other pterosaurs. Juvenile development was probably rapid, with evidence from other pterosaur species suggesting young could fly relatively soon after hatching, though the massive size of adult Quetzalcoatlus indicates its young may have had a longer growth period before achieving full flight capability.

Scientific Discoveries and Fossil History

The fossil history of these creatures reflects the challenges of preserving the delicate bones of flying animals. Pteranodon was among the first pterosaurs well-known to science, with initial discoveries dating back to 1870 by American paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh. Its relatively numerous fossils (over 1,000 specimens) from the Niobrara Formation have made it one of the best-understood pterosaurs, though complete skeletons remain rare. Quetzalcoatlus has a much briefer scientific history, first described in 1975 based on a partial wing discovered in Texas by graduate student Douglas Lawson. The type species, Quetzalcoatlus northropi, was named for the aircraft designer John Northrop, whose flying wing designs seemed to parallel the pterosaur’s massive wingspan. Despite its iconic status, Quetzalcoatlus remains known from surprisingly few specimens, with much of our understanding based on fragmentary remains and more complete fossils of related azhdarchid pterosaurs. This limited fossil record has fueled ongoing debates about its exact size, appearance, and behavior, with discoveries and analytical techniques continually refining our understanding of this aerial giant.

Cultural Impact and Common Misconceptions

Both pterosaurs have secured prominent places in popular culture, though often with significant inaccuracies. Pteranodon is frequently mislabeled as a “pterodactyl” in movies and children’s books, despite Pterodactylus being a different, much smaller European pterosaur. Media depictions commonly show Pteranodon capable of picking up humans or large animals on their feet like eagles, despite lacking the strong grasping talons necessary for such feats. Quetzalcoatlus suffers from its misrepresentations, often incorrectly portrayed as a giant scavenger circling battlefields or depicted with an impossibly massive body relative to its already impressive actual size. Both creatures are routinely shown with bat-like wing membranes rather than the complex four-layered flight membranes paleontologists now know pterosaurs possessed. Perhaps most persistently, both are frequently depicted as dinosaurs, despite belonging to a separate reptile lineage that evolved flight independently. These popular misconceptions continue to shape public perception of these animals, despite scientific advances that have given us increasingly accurate understandings of how these remarkable creatures lived and flew.

Extinction Patterns and Legacy

The end of these aerial giants tells two different extinction stories. Pteranodon disappeared approximately 84.5 million years ago, well before the end-Cretaceous mass extinction event, likely due to ecological changes in its marine ecosystem and competition from other marine flying reptiles and early seabirds. Its disappearance represents a normal turnover in the pterosaur evolutionary timeline rather than a catastrophic event. Quetzalcoatlus, however, persisted until the very end of the Cretaceous period and was among the last pterosaur lineages to exist before being eliminated in the mass extinction event 66 million years ago that also claimed the non-avian dinosaurs. This dramatic difference in extinction timing highlights how these pterosaurs, despite their superficial similarities as flying reptiles, had entirely different evolutionary trajectories and fates. After their extinction, the ecological niches they occupied remained largely unfilled for millions of years until large soaring birds like teratorns and pelagornithids evolved to claim similar aerial domains, though none would ever match the spectacular size achieved by Quetzalcoatlus, truly the largest animal ever to conquer Earth’s skies.

Conclusion

The comparison between Quetzalcoatlus and Pteranodon reveals how evolution crafted remarkably different flying specialists from the same ancestral stock. While Pteranodon soared over ancient seas hunting fish with its specialized beak, Quetzalcoatlus stalked terrestrial landscapes as the largest flying creature in Earth’s history. Despite often being confused or conflated in popular culture, these pterosaurs were separated by millions of years, distinct habitats, and divergent adaptations. Their differences illustrate the remarkable diversity of the pterosaur lineage and demonstrate how flight evolved.