In the early nineteenth century, as the first dinosaur fossils were being scientifically classified, a profound intellectual challenge emerged within Christian communities across Europe and America. The discovery of creatures that appeared nowhere in scripture—massive reptilian beasts that had dominated Earth long before humans—created a theological crisis that would reshape religious thought. These ancient bones told a story seemingly at odds with the biblical timeline of a 6,000-year-old Earth created in six days with all creatures formed simultaneously. This article explores how Christian denominations and religious thinkers confronted, resisted, and ultimately adapted to the revolutionary implications of paleontological discoveries that questioned fundamental interpretations of Genesis.

The First Dinosaur Discoveries and Initial Religious Confusion

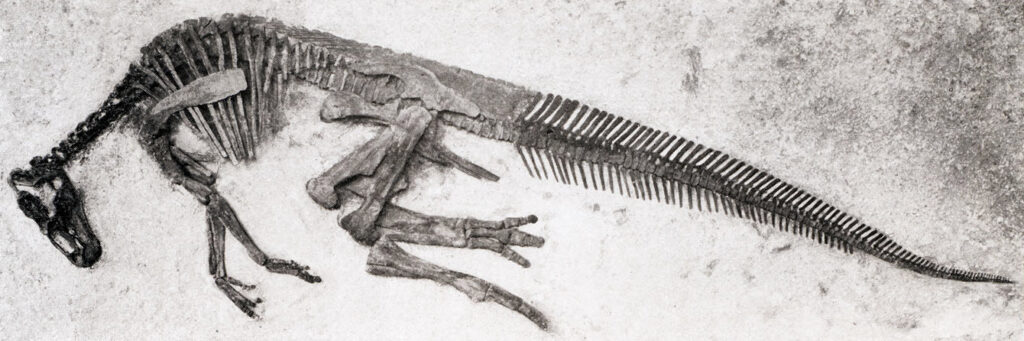

The scientific recognition of dinosaurs began in the early 1800s, with formal naming occurring in 1842 when Sir Richard Owen coined the term “Dinosauria,” meaning “terrible lizards.” Before this taxonomic classification, giant bones had been unearthed across Europe and America, with some initially misidentified as the remains of biblical giants or victims of Noah’s flood. When Mary Anning discovered complete ichthyosaur and plesiosaur fossils along England’s Jurassic Coast beginning in 1811, and later when William Buckland described the first Megalosaurus in 1824, religious authorities faced perplexing evidence. Early reaction from church officials often involved attempts to incorporate these findings into the existing biblical framework, suggesting these creatures had been drowned in the Great Flood. However, as the sheer antiquity and diversity of these creatures became apparent, simple explanations became increasingly difficult to maintain, creating significant theological discomfort that would require more sophisticated responses.

The Biblical Timeline Under Pressure

The traditional Biblical chronology, carefully calculated by 17th-century Archbishop James Ussher, placed Earth’s creation at precisely 4004 BCE, making the planet approximately 6,000 years old. This timeline left no room for the extensive geological periods required for dinosaur evolution, fossilization, and extinction. When Georges Cuvier demonstrated that fossils represented extinct species from a pre-human era, and when geologists like Charles Lyell established that Earth’s features required millions of years to form, religious authorities faced a serious interpretive challenge. Many church leaders initially responded with skepticism toward the emerging sciences, questioning the methodology and assumptions of geologists and paleontologists. Some influential religious thinkers specifically attacked the nascent concept of “deep time,” arguing that the appearance of great age was misleading, perhaps even a divine test of faith. This tension created a pivotal moment for Biblical hermeneutics, forcing Christian thinkers to reconsider how certain passages should be interpreted.

Catastrophism as a Compromise Theory

One of the earliest attempts to reconcile dinosaur fossils with Genesis came through catastrophism, a geological theory championed by naturalists like Georges Cuvier and initially embraced by many religious scientists. Catastrophism proposed that Earth’s history was marked by a series of global cataclysms, with Noah’s flood representing just the most recent disaster. This theory allowed religious thinkers to acknowledge fossil evidence while maintaining some biblical literalism, suggesting that dinosaurs had lived and died in earlier epochs or “worlds” before the current creation. William Buckland, an Anglican priest and Oxford geology professor, became catastrophism’s most prominent religious defender, attempting to demonstrate scientifically that a universal deluge had occurred. In his 1823 work “Reliquiae Diluvianae” (Relics of the Flood), Buckland initially argued that geological evidence supported the biblical flood narrative, though he later modified his views as evidence mounted against a single global catastrophe. Catastrophism offered temporary comfort to religious institutions facing scientific challenges, but ultimately proved unsustainable as a comprehensive explanation.

The Gap Theory: Finding Space for Dinosaurs

As direct contradictions between fossil evidence and literal Bible readings became increasingly difficult to ignore, the “Gap Theory” emerged as an influential theological response. Developed by Scottish theologian Thomas Chalmers in the 1810s and popularized by the Scofield Reference Bible in the early 1900s, this interpretation proposed a vast time gap between Genesis 1:1 (“In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth”) and Genesis 1:2 (“And the earth was without form, and void”). This exegetical approach suggested that dinosaurs and other prehistoric creatures had existed during this unspecified interval before being destroyed in a cataclysm preceding the six-day creation described in the rest of Genesis 1. The Gap Theory gained significant popularity among educated Christians because it required minimal adjustment to traditional biblical interpretation while accommodating scientific discoveries. Religious leaders who embraced this view could accept the reality of dinosaurs while maintaining that Adam and Eve were still the first humans, created specially by God approximately 6,000 years ago in a world remade after the destruction of the dinosaurs.

Day-Age Theory: Redefining Biblical Days

Another interpretive approach that gained traction among religiously inclined scientists and theologically progressive clergy was the Day-Age Theory, which proposed that each “day” in Genesis represented not 24 hours but extended geological epochs. This interpretation found biblical support in passages like 2 Peter 3:8, which states that “one day is with the Lord as a thousand years, and a thousand years as one day.” Presbyterian theologian Benjamin Warfield and Scottish geologist Hugh Miller became prominent advocates of this view, suggesting that the creation sequence in Genesis aligned with scientific understanding of Earth’s development if each “day” represented millions of years. Under this framework, dinosaurs could be understood as created during the fifth and sixth days alongside other animals, eventually going extinct before human creation at the end of the sixth day.” The Day-Age Theory proved particularly appealing to denominations emphasizing education and intellectual engagement, as it preserved biblical authority while acknowledging scientific evidence. This interpretation remains influential among religious scientists today, particularly those in organizations like the American Scientific Affiliation who seek harmony between faith and science.

Catholic Responses and Theological Flexibility

The Catholic Church’s institutional response to dinosaur discoveries demonstrated greater theological flexibility than many Protestant denominations initially showed. Unlike more literalist Protestant groups, Catholic theology had long incorporated natural law alongside divine revelation, following Thomas Aquinas’s teaching that scientific and biblical truths could not fundamentally contradict each other. In 1950, Pope Pius XII’s encyclical “Humani Generis” officially acknowledged that Catholic faith was compatible with evolutionary theory as a scientific explanation for biological diversity, including extinct species like dinosaurs. This position continued evolving under subsequent popes, with John Paul II stating in 1996 that evolution was “more than just a hypothesis.” Catholic educational institutions generally incorporated paleontological findings into their curricula without perceiving a threat to faith, and prominent Catholic scientists like paleontologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin developed sophisticated theological frameworks integrating evolution into Christian cosmology. The Catholic approach exemplified how established religious institutions with centralized authority could adapt official doctrine to accommodate scientific discoveries without perceiving fundamental threats to religious identity.

Fundamentalist Rejection and Young Earth Creationism

While many Christians found ways to reconcile dinosaur fossils with their faith, a significant countermovement emerged that rejected paleontological timelines entirely. This position, later formalized as Young Earth Creationism, insisted on a literal six-day creation approximately 6,000 years ago, with all animal kinds—including dinosaurs—created simultaneously. The 1961 publication of “The Genesis Flood” by John Whitcomb and Henry Morris provided pseudo-scientific arguments for this view, suggesting that Noah’s flood created fossil deposits and that dinosaurs were contemporary with early humans. This position gained significant traction among conservative evangelical and fundamentalist denominations in America, leading to the establishment of institutions like the Institute for Creation Research and the Creation Museum, which depicts humans and dinosaurs coexisting. Young Earth Creationism represents perhaps the most direct rejection of mainstream paleontology, arguing that scientific consensus about dinosaur extinction 65 million years ago reflects anti-religious bias rather than evidence. This movement has profoundly influenced American religious education and remains a powerful force in debates about science curriculum in public schools.

Scriptural Reinterpretation: Finding Dinosaurs in the Bible

Some religious thinkers took a different approach by suggesting that dinosaurs were mentioned in scripture, just not by that name. They pointed to biblical passages describing creatures like “behemoth” in Job 40, which is characterized as having a “tail like a cedar” and “limbs like bars of iron,” or the sea monster “leviathan” in Job 41, as possible references to dinosaurs or other prehistoric creatures. This interpretive strategy allowed believers to claim that scripture had acknowledged these creatures all along, even predating scientific discovery. Ken Ham’s Answers in Genesis ministry has particularly championed this view, producing educational materials suggesting that “dragons” mentioned in various cultures were based on human encounters with surviving dinosaurs. However, mainstream biblical scholars and paleontologists have generally rejected these interpretations, noting that behemoth more likely referred to contemporary animals like hippopotamuses or elephants, while leviathan descriptions align with crocodiles or mythological creatures. Nevertheless, this approach remains popular among those seeking to maintain biblical inerrancy while acknowledging dinosaurs’ historical existence.

Clergy-Scientists: Navigating Dual Identities

An intriguing aspect of the church’s early response to dinosaur discoveries was the significant role played by clergy-scientists who personally navigated the intersection of religious and scientific authority. Many early paleontologists were themselves ordained ministers who saw no fundamental conflict between their scientific work and religious vocation. The Reverend William Buckland, who described the first dinosaur (Megalosaurus) in scientific literature, served as Dean of Westminster while holding the Oxford chair of geology. Similarly, Edward Hitchcock, a Congregationalist pastor who became president of Amherst College, conducted pioneering work on dinosaur footprints while maintaining his faith. These dual-identity figures often developed nuanced theological positions that influenced their denominations’ official responses. Their intellectual journeys—sometimes involving painful reassessment of previously held beliefs—created pathways for their religious communities to engage with new scientific information without wholesale rejection of tradition. The clergy-scientist phenomenon decreased through the nineteenth century as both fields professionalized, but these early figures demonstrated that religious leadership and scientific inquiry could coexist in the same individual.

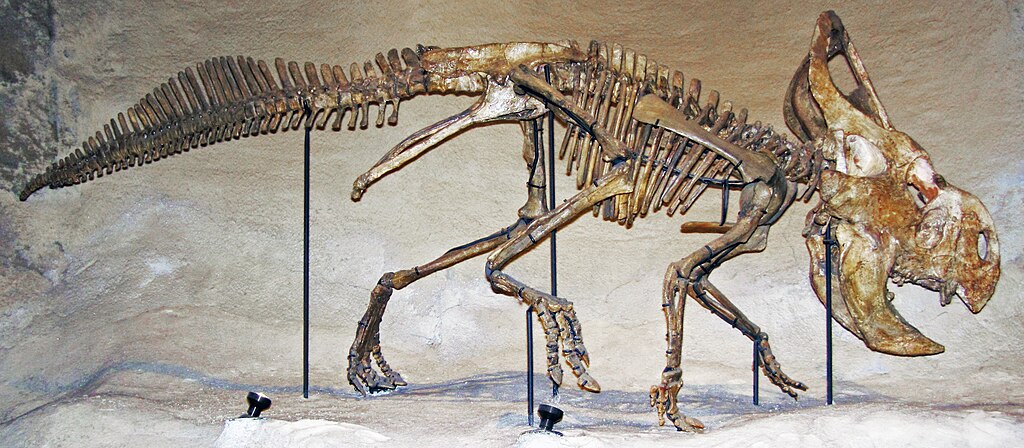

Museum Culture and Public Understanding

As natural history museums began displaying dinosaur fossils to the public in the mid-nineteenth century, these institutions became important sites where religious communities encountered and processed challenges to traditional beliefs. The Crystal Palace dinosaur models, unveiled in London in 1854, represented the first major public display of these prehistoric creatures, while the American Museum of Natural History’s first mounted dinosaur skeleton in 1868 became a sensation that both fascinated and troubled religious visitors. Church leaders recognized these museums’ powerful influence on public understanding and responded with varying approaches. Some religious groups organized guided tours offering faith-compatible interpretations of exhibits, while others discouraged attendance entirely. Museum directors like Richard Owen in Britain and Edward Drinker Cope in America negotiated these tensions carefully, often framing dinosaur displays in ways that minimized confrontation with religious sensibilities. The spectacular nature of mounted dinosaur skeletons made theoretical debates about geology and scripture concrete for ordinary believers, forcing religious communities to develop practical responses to paleontological evidence that extended beyond academic theological adjustments.

Religious Education Responses and Children’s Literature

The challenge of explaining dinosaurs to children within religious contexts created particular pressure on church educational systems and religious publishing. Sunday school curricula and religious children’s literature needed to address creatures that fascinated young minds while maintaining doctrinal positions. By the early twentieth century, different denominational approaches had emerged in educational materials. Mainline Protestant publishers generally incorporated dinosaurs into creation narratives that acknowledged their prehistoric existence, while more conservative materials either omitted dinosaurs entirely or presented them as contemporaneous with biblical events. Catholic educational materials typically presented dinosaurs within a framework compatible with both scripture and science, consistent with the church’s more accommodating stance toward evolutionary timeframes. The publication of explicitly creationist children’s books accelerated in the 1970s, presenting alternative narratives like dinosaurs on Noah’s ark. These educational choices reflected deeper theological positions and significantly shaped how generations of religious children reconciled their faith with scientific information they encountered in school and popular culture.

Modern Religious Paleontologists and Evolving Perspectives

The contemporary landscape of religious responses to dinosaurs has been significantly influenced by the emergence of openly religious paleontologists who fully accept mainstream scientific chronologies while maintaining their faith. Scientists like Francis Collins, who led the Human Genome Project while publishing about his evangelical Christian faith, have created intellectual space for religious believers to accept evidence for Earth’s ancient history. Religious paleontologists like Robert Bakker, who revolutionized understanding of dinosaur behavior while maintaining his Pentecostal faith, demonstrate ongoing integration possibilities. These figures often articulate sophisticated theological positions that separate scientific questions (how and when dinosaurs lived) from religious ones (why they existed and what meaning their existence might hold). Many religious colleges that once rejected paleontological timelines now maintain geology departments that teach mainstream science while offering theological frameworks for interpretation. This evolving perspective has produced significant denominational shifts, with many religious groups that once opposed evolutionary timelines now accepting the scientific consensus about dinosaurs while maintaining distinct theological understandings about divine purpose and human uniqueness.

The Ongoing Cultural Legacy of the Dinosaur-Religion Conflict

The early tensions between paleontological discoveries and religious interpretations continue to shape American cultural and political landscapes in profound ways. The 1925 Scopes “Monkey Trial,” though technically focused on human evolution rather than dinosaurs, exemplified how fossils had become cultural battlegrounds with religious significance. More recent legal battles over teaching evolution in public schools, such as Kitzmiller v. Dover in 2005, have similarly focused on who controls narratives about prehistoric life. The ongoing popularity of creation museums that present alternative views of dinosaur history, alongside the mainstream success of institutions like the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, demonstrates America’s continuing cultural divide. This scientific-religious tension has transcended purely theological concerns to influence political affiliations, educational choices, and cultural identities. The specific ways religious communities initially responded to dinosaur discoveries established patterns of science engagement, ranging from integration to opposition, that continue to influence how these same communities approach contemporary scientific issues like climate change and genetic engineering.

Conclusion

The discovery of dinosaur fossils presented nineteenth-century Christianity with one of its most significant intellectual challenges, forcing religious communities to reconsider deeply held beliefs about Earth’s timeline and the relationship between scripture and natural evidence. The varied theological responses—from outright rejection to sophisticated reinterpretation—demonstrated both the flexibility and constraints of religious thought when confronted with revolutionary scientific discoveries. Rather than producing a single unified “church reaction,” dinosaur fossils catalyzed a spectrum of responses that reflected existing theological divisions while creating new ones. This historical episode provides valuable perspective on contemporary science-religion discussions, demonstrating that religious worldviews can adapt to accommodate new scientific understanding, though often through complex and sometimes contentious processes. Today’s religious perspectives on dinosaurs continue to reflect this diverse legacy, with positions ranging from young-earth creationism to fully integrated evolutionary understandings, each claiming authentic religious fidelity while drawing different boundaries around scientific authority.