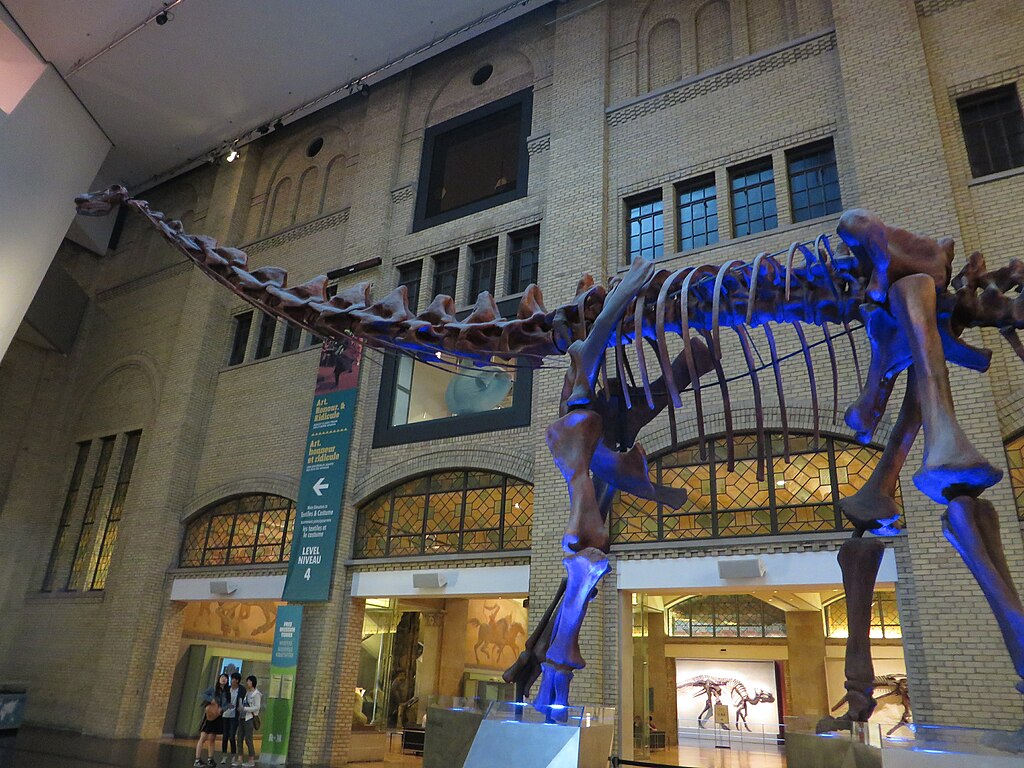

The majestic fossils of ancient dinosaurs that captivate us in museum displays represent more than just scientific treasures—they’re irreplaceable windows into Earth’s distant past. Yet beyond the carefully curated exhibits lies a shadowy world where these priceless specimens are treated as commodities, traded illegally for enormous sums of money. The black market for dinosaur fossils has flourished in recent decades, creating a lucrative underground economy that threatens paleontological research, damages fragile excavation sites, and undermines our collective natural heritage. As prices for premier specimens reach into the millions, the incentive for illegal excavation and trafficking has intensified, creating an urgent crisis for scientists, law enforcement, and governments worldwide. This illicit trade doesn’t just represent lost specimens—it represents lost knowledge about our planet’s evolutionary history.

The Scope of the Illegal Fossil Trade

The black market for dinosaur bones operates on a surprisingly vast global scale, with annual estimates ranging from $100 million to over $500 million in illegal sales. This underground economy spans continents, connecting fossil-rich regions like Mongolia’s Gobi Desert, China’s Liaoning Province, and the American Southwest with wealthy private collectors in Europe, Asia, and North America. While exact figures remain elusive due to the secretive nature of the trade, high-profile cases reveal the extraordinary values involved, like the 2012 auction of a Tarbosaurus bataar skeleton that commanded $1.05 million before being identified as illegally exported from Mongolia. The digital age has transformed this illicit market, with online auctions and private messaging platforms facilitating anonymous transactions that bypass traditional regulatory channels. Some experts believe the publicly visible cases represent merely the tip of a much larger iceberg of illegal fossil trafficking.

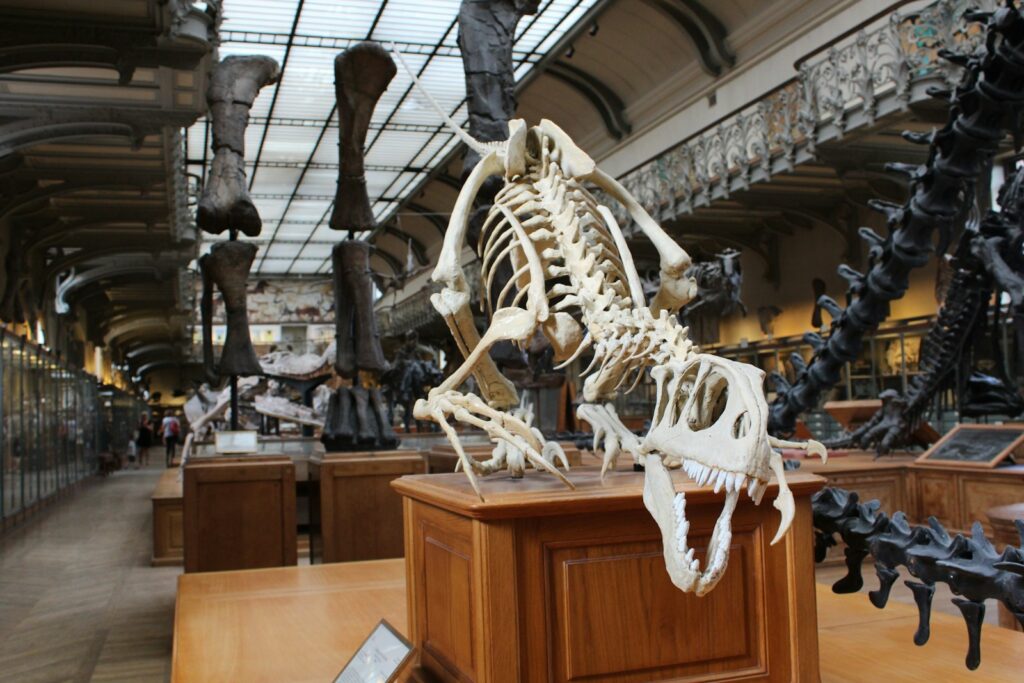

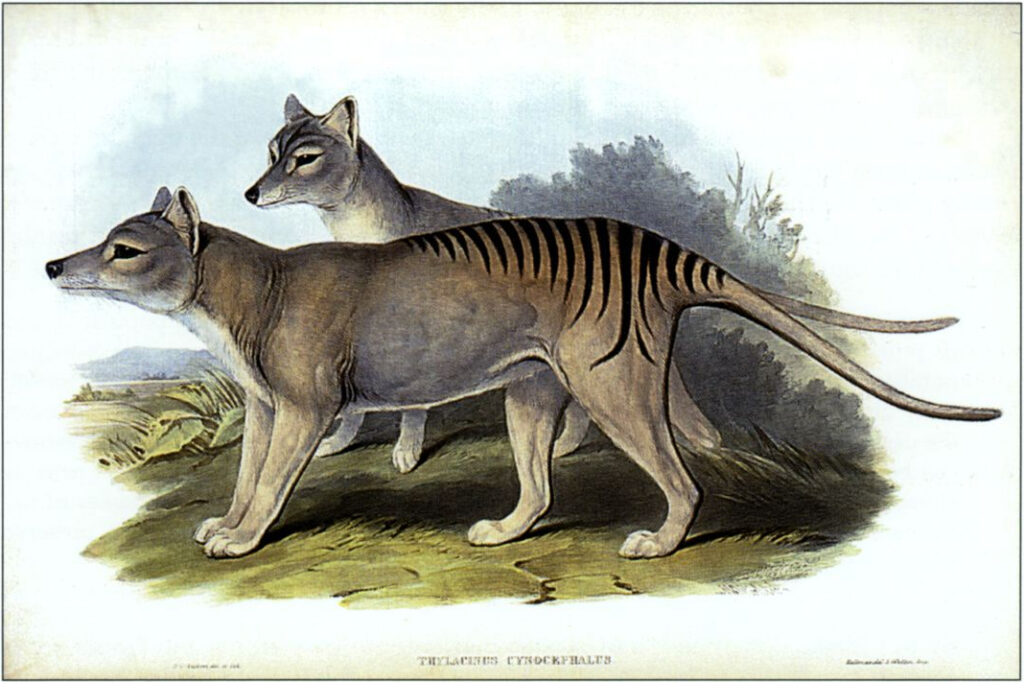

The Most Coveted Specimens

Not all dinosaur fossils command equal attention on the black market, with certain specimens fetching astronomical prices due to their rarity, completeness, or aesthetic appeal. Complete skulls and articulated skeletons of iconic predators like Tyrannosaurus rex and Velociraptor routinely top the most-wanted list, with well-preserved examples potentially worth millions. Specimens with unusual features—such as evidence of pathologies, exceptional preservation of soft tissues, or rare behavioral moments like fighting or nesting—command premium prices for their scientific significance and display value. The fossil black market also places extraordinary value on transitional forms that illustrate evolutionary developments, such as feathered dinosaurs that demonstrate the dinosaur-bird connection. Paradoxically, the scientific importance of a specimen often correlates directly with its black market value, meaning the fossils most crucial for research are precisely those most targeted by illegal collectors and dealers.

How Fossils Enter the Black Market

The journey of an illegally traded fossil typically begins with unauthorized excavations in fossil-rich regions, often conducted hastily by untrained individuals using improper techniques that damage specimens and destroy contextual information. In countries like Mongolia, China, and Morocco, networks of local diggers may be hired by middlemen who provide basic tools and rudimentary instruction but little scientific guidance or documentation. Once extracted, fossils move through a series of intermediaries who falsify documentation, obscure the specimen’s origin, or smuggle materials across borders through commercial shipping disguised as art objects, furniture, or construction materials. Sophisticated fossil laundering operations may route specimens through countries with less stringent export regulations or fabricate convincing but fraudulent provenance documents that misrepresent when and where specimens were collected. Some black market fossils even enter legitimate channels through commercial fossil shows or auctions with deliberately vague descriptions of their origins.

The Scientific Cost of Fossil Trafficking

When fossils are illegally excavated, the scientific community loses far more than just the physical specimens—it loses irreplaceable contextual information that gives those specimens meaning. Professional paleontologists meticulously document the precise position, orientation, and geological context of each fossil, data that reveals crucial information about the ancient environment, the animal’s behavior at the time of death, and its relationship to other organisms in its ecosystem. Black market excavations typically discard this context entirely, focusing solely on extracting visually impressive pieces while discarding fragmentary remains that might complete the scientific picture. Many illegally excavated specimens are damaged during hasty extraction, with delicate structures broken or improperly preserved, and potentially groundbreaking specimens have been irreparably harmed by untrained handling. Perhaps most devastating is the permanent loss of scientific access, as specimens disappearing into private collections become unavailable for comparative study, preventing researchers from testing hypotheses or making discoveries from these materials.

Major Source Countries and Their Vulnerabilities

Certain countries have become particularly susceptible to fossil poaching due to their rich paleontological resources combined with challenging economic conditions and limited enforcement capabilities. Mongolia’s Gobi Desert contains extraordinarily rich Late Cretaceous deposits with remarkably preserved dinosaurs, yet its vast, sparsely populated terrain makes comprehensive monitoring nearly impossible despite strong national laws protecting fossils. China’s Liaoning Province, famous for its feathered dinosaur specimens and exquisitely preserved fossils in the Jehol Biota, struggles with illegal excavation despite increasingly stringent enforcement. Morocco’s phosphate deposits and dinosaur-rich areas in the Atlas Mountains region have developed sophisticated networks of local excavators feeding international markets, sometimes operating in gray areas of inconsistently enforced regulations. The United States faces significant challenges in the American West, particularly on public and private lands in Montana, Wyoming, and South Dakota, where the boundaries between legal commercial collection and illegal activities often blur. Brazil, Argentina, and Madagascar have all experienced increasing pressure from international fossil traffickers targeting their unique paleontological heritage.

The Market Drivers: Collectors and Status Symbols

The ultimate engine driving the illegal fossil trade is demand from wealthy private collectors who view dinosaur fossils as ultimate status symbols and conversation pieces. High-net-worth individuals in technology, entertainment, and finance sectors have increasingly embraced dinosaur specimens as dramatic home décor and investment assets, with some viewing them as alternatives to traditional art investments. This collector market has transformed dramatically in recent decades, as specimens once valued primarily by scientific institutions now command prices comparable to fine art masterpieces. Celebrity collectors have inadvertently normalized and glamorized private fossil ownership, with high-profile purchases by actors, musicians, and business leaders generating media attention that further stimulates market demand. Some collectors genuinely appreciate the scientific and historical significance of their acquisitions, while others view them primarily as investment vehicles or decorative objects, often displaying limited concern for proper documentation or scientific access. The competitive nature of high-end collecting creates bidding wars for premier specimens, driving prices to levels that incentivize continued illegal excavation and trafficking.

Legal Ambiguities and Enforcement Challenges

Combating the illegal fossil trade is complicated by a patchwork of inconsistent laws and regulations that vary dramatically between countries and even between regions within countries. While nations like Mongolia maintain that all fossils within their borders are national property and cannot be privately owned, the United States allows private ownership of fossils found on private land, creating a legally permissible commercial market that can serve as cover for illicitly obtained specimens. Enforcement agencies face substantial challenges in distinguishing legally collected fossils from illegal ones, particularly when provenance documentation is limited, falsified, or deliberately vague about a specimen’s origins. International cooperation between law enforcement agencies remains incomplete, with limited resources devoted to fossil trafficking compared to other smuggling priorities like narcotics or weapons. Even when illegal specimens are identified, the complex legal process of repatriation can take years, as demonstrated by the lengthy proceedings required to return the famous smuggled Tarbosaurus bataar skeleton to Mongolia after its 2012 auction identification.

High-Profile Cases and Prosecutions

Several landmark legal cases have highlighted the scope and significance of the fossil black market. The 2012 case of Eric Prokopi, self-described “commercial paleontologist,” resulted in a high-profile prosecution after he attempted to sell a complete Tarbosaurus bataar skeleton illegally removed from Mongolia. Following his guilty plea, Prokopi received a three-month prison sentence and forfeited multiple dinosaur specimens that were subsequently repatriated to Mongolia. The 1997 “Sue” Tyrannosaurus rex case illustrated the complex legal questions surrounding fossil ownership, as this exceptional specimen was seized by the FBI from its discoverers amid disputes over land ownership rights before eventually selling at auction for $8.4 million to Chicago’s Field Museum. In 2020, federal prosecutors in Wyoming charged two commercial fossil dealers with conspiracy, theft, and depredation of government property for illegally collecting fossils from federal lands and selling them internationally. The case against actor Nicolas Cage, who voluntarily returned a Tyrannosaurus bataar skull to Mongolia in 2015 after learning it had been illegally exported, demonstrated how even well-intentioned collectors can unwittingly participate in the illegal trade.

The Ethics of Commercial Fossil Collecting

The relationship between commercial fossil collecting and scientific institutions remains contentious, with legitimate debates about where appropriate boundaries should be drawn. Professional commercial fossil hunters argue they rescue specimens that would otherwise erode and be lost to science, while providing necessary expertise and resources that cash-strapped academic institutions cannot match. Many reputable commercial collectors maintain careful documentation practices, work with scientific experts, and ensure important specimens reach museums rather than private collections. However, critics maintain that commercialization fundamentally transforms fossils from scientific resources into commodities, distorting incentives and encouraging speed over careful methodological excavation. This tension plays out differently across countries, with some nations banning all commercial collection while others, like the United States, maintain a mixed system that allows commercial collection on certain private lands. The ethical complexities extend to museums themselves, which sometimes rely on donations or purchases from commercial sources to acquire important specimens they could not otherwise afford, potentially creating indirect incentives for continued commercial collection.

Digital Technology and the Changing Black Market

The evolution of digital technologies has transformed the illegal fossil trade, creating both new opportunities for traffickers and new tools for enforcement. Online auction platforms, specialized websites, and private messaging applications now facilitate anonymous global transactions that would have been impossible in previous decades, allowing buyers and sellers to connect across international boundaries with minimal scrutiny. Social media platforms inadvertently serve as advertising venues where sellers can reach potential buyers while maintaining plausible deniability about their intentions to sell protected specimens. At the same time, digital photography and imaging technologies help enforcement agencies document suspected illegal specimens and compare them with databases of known stolen fossils. Advanced scanning technologies allow researchers to create detailed digital models of specimens in legitimate collections, preserving scientific data even when physical specimens might be at risk of theft or trafficking. The cryptocurrency revolution has further complicated tracking of payments for illegal specimens, with untraceable transactions adding another layer of anonymity to the black market.

Museum Acquisition Policies and Ethical Dilemmas

Natural history museums worldwide face increasingly difficult ethical questions regarding fossil acquisitions in an era of rampant fossil trafficking. Many major institutions have adopted stringent acquisition policies requiring comprehensive documentation of a specimen’s provenance, legal excavation permits, and export documentation before considering purchases or donations. The Society of Vertebrate Paleontology has established ethical guidelines recommending that members avoid studying or publishing research on potentially illegally collected specimens, as scientific attention can inadvertently increase black market values. Museums must balance their scientific mission to preserve important specimens against the risk that purchasing fossils might indirectly incentivize further illegal collection. Some institutions have pioneered collaborative arrangements with fossil-rich countries, developing partnerships where specimens can be studied by international teams while ultimate ownership remains with the country of origin. When faced with specimens of exceptional scientific importance but questionable provenance, museum curators and administrators navigate complex ethical territory, weighing the scientific loss if specimens remain unstudied against the potential legitimization of improper collection practices.

Conservation Efforts and International Cooperation

Addressing the fossil black market effectively requires coordinated international response strategies that address both supply and demand aspects of the trade. Organizations like INTERPOL have expanded their focus on cultural property crimes to include paleontological resources, facilitating cross-border investigations and information sharing about trafficking networks. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) framework, while primarily focused on living species, provides a potential model for tracking and regulating the international movement of significant paleontological specimens. Several countries have implemented innovative educational programs targeting local communities in fossil-rich regions, creating economic alternatives to illegal excavation through sustainable scientific tourism or training residents as legitimate fossil preparators. Mongolia’s Institute for Paleontology and Geology has partnered with international organizations to conduct comprehensive inventory programs documenting known specimens in foreign collections to aid in identifying potentially smuggled materials. Digital databases shared between countries help track stolen specimens and provide crucial evidence for repatriation claims, while collaborative training programs help build enforcement capacity in countries with limited resources.

The Future of Fossil Protection

Protecting dinosaur fossils from illegal trafficking will require evolving approaches that adapt to changing market conditions and technological developments. Emerging genetic technologies may soon enable reliable geographic origin determination for fossils through analysis of trace DNA or geological markers, making it harder to falsify provenance documentation. Blockchain certification systems offer potential for creating tamper-proof digital records of a specimen’s discovery, legal excavation permits, and chain of custody. Several countries are exploring expanded use of in-situ conservation, where significant fossil discoveries are protected and developed as scientific and tourism resources rather than being excavated, preserving their full contextual information while providing sustainable economic benefits to local communities. Educational initiatives targeting potential collectors and auction houses may help reduce market demand by highlighting the scientific cost of private fossil ownership and encouraging philanthropic support of public institutions instead. Some experts advocate for creating legitimate, regulated markets for certain common fossil types while maintaining strict protections for scientifically significant specimens, channeling commercial interest into sustainable practices rather than trying to eliminate it.

Preserving Prehistoric Heritage from Fossil Trafficking

The black market for dinosaur fossils represents a critical conservation challenge that transcends simple law enforcement, touching on complex questions of scientific access, cultural heritage, and national sovereignty. These irreplaceable resources—the physical evidence of Earth’s evolutionary history—deserve protection not simply as valuable objects but as sources of knowledge that belong to humanity collectively. By strengthening international cooperation, addressing economic root causes, and fostering ethical collecting practices, we can work toward preserving these windows into prehistoric worlds for scientific study and public appreciation. Every illegally trafficked fossil represents not just a lost specimen but lost knowledge about our planet’s remarkable past—a history that, once erased, cannot be recovered.