When we imagine dinosaurs thundering across prehistoric landscapes, speed is often a captivating element of these ancient creatures. While the enormous Brachiosaurus and mighty Tyrannosaurus rex capture our imagination with their size and power, certain dinosaur species evolved for remarkable velocity. Using a combination of fossil evidence, biomechanical analysis, and comparisons with modern animals, paleontologists have developed increasingly accurate estimates of dinosaur locomotion capabilities. These prehistoric speed demons evolved various adaptations, from lightweight skeletons to specialized leg muscles, allowing them to achieve impressive velocities that would rival modern animals. This ranking explores the fastest dinosaurs that ever lived, examining not just how fast they could move but why speed was crucial to their survival in the dangerous world of the Mesozoic Era.

Understanding Dinosaur Speed: How Scientists Make Their Estimates

Determining how fast extinct animals moved presents significant scientific challenges, requiring multiple lines of evidence. Paleontologists analyze fossilized trackways, measuring stride length and patterns to calculate potential speeds. Biomechanical modeling provides another crucial approach, where scientists examine leg bone proportions, muscle attachment sites, and joint construction to assess movement capabilities. Computer simulations have revolutionized this field, allowing researchers to create detailed models that account for body mass, center of gravity, and other physical factors. Additionally, comparative anatomy with living relatives like birds provides valuable insights, as does examining ecological niches—predators typically need sufficient speed to capture prey, while prey species require adequate velocity to escape threats. These methodologies combined offer increasingly refined estimates, though exact speeds remain subject to ongoing research and debate.

Velociraptor: Not As Fast As Hollywood Suggests

Despite its fearsome portrayal in popular films like “Jurassic Park,” Velociraptor was not the lightning-fast predator often depicted in entertainment. Standing approximately 1.6 feet (0.5 meters) tall and weighing around 33 pounds (15 kilograms), the actual Velociraptor was much smaller than its movie counterpart, closer in size to a turkey than a man. Scientific analysis suggests these dromaeosaurids could reach speeds of approximately 24-25 mph (39-40 km/h)—impressive but far from the fastest dinosaurs. Their primary hunting advantage came not from raw speed but from maneuverability, problem-solving intelligence, and pack hunting behaviors. Paleontologists believe Velociraptors were more like agile ambush predators, using their infamous curved claws to latch onto prey after short, explosive bursts of speed rather than maintaining high velocities over long distances. This hunting strategy would have been particularly effective in the densely vegetated environments of the Late Cretaceous period.

Gallimimus: The Ostrich Mimic Built for Speed

Gallimimus stands as one of the most impressive speed specialists among dinosaurs, with physical adaptations explicitly evolved for rapid movement. This ostrich-like ornithomimid dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous period featured a lightweight frame, hollow bones, and exceptionally long, slender legs designed for covering ground efficiently. Growing up to 20 feet (6 meters) in length, Gallimimus possessed a distinctive combination of a small head, long neck, and aerodynamic body that minimized wind resistance. Biomechanical studies suggest Gallimimus could achieve speeds of approximately 30-35 mph (48-56 km/h), comparable to modern ostriches. Their feet featured three forward-facing toes that provided excellent traction and shock absorption during high-speed running across the ancient Mongolian plains. As a primarily herbivorous species, this impressive velocity served primarily as a defense mechanism, allowing Gallimimus to flee from larger predators rather than pursue prey.

Compsognathus: Small Size, Surprising Speed

Compsognathus proves that impressive velocity wasn’t exclusive to larger dinosaurs, with this chicken-sized theropod achieving remarkable speeds despite its diminutive stature. Weighing only about 6-7 pounds (2.5-3.5 kg) and measuring roughly 3 feet (1 meter) in length, Compsognathus combined lightweight construction with powerfully built hind limbs. Biomechanical analysis of their well-preserved fossils suggests these Late Jurassic predators could reach speeds of approximately 25 mph (40 km/h), making them among the fastest small dinosaurs. Their velocity would have been crucial for hunting small prey like lizards and insects while also helping them escape larger predators. Interestingly, Compsognathus’ speed capabilities may have represented an early evolutionary development of the rapid locomotion that would later become more pronounced in their avian descendants. The impressive speed-to-size ratio of Compsognathus demonstrates the remarkable diversity of locomotion strategies that evolved among different dinosaur lineages.

Tyrannosaurus Rex: Faster Than You Might Think

The iconic Tyrannosaurus rex has been the subject of significant debate regarding its locomotion capabilities, with scientific understanding evolving considerably over time. While early research suggested this seven-ton predator might have been limited to walking speeds, more recent biomechanical models indicate T. rex was moderately fast for its massive size. Current estimates place adult T. rex’s top speed at approximately 12-17 mph (20-27 km/h)—not as swift as smaller theropods but still surprisingly quick for an animal weighing as much as an elephant. This speed would have allowed T. rex to overtake many potential prey animals that couldn’t sustain higher speeds over distance. Anatomical evidence indicates T. rex had proportionally massive leg muscles and specialized weight-bearing adaptations that facilitated this unexpected mobility. Juvenile T. rex specimens likely moved considerably faster than adults, potentially reaching 20 mph (32 km/h) before their massive growth spurt added significant body weight that would have limited their top speed.

Carnotaurus: The Bull-Horned Speed Demon

Carnotaurus stands out among large theropods for its extraordinary adaptations, specifically evolved for high-velocity pursuit. This distinctive Late Cretaceous predator featured remarkably long, slender hindlimbs with specialized muscle attachments that paleontologists believe provided exceptional running ability. Most striking were its extremely reduced forelimb, even smaller proportionally than those of T. rex, which reduced frontal weight and wind resistance. Biomechanical studies of its unusually well-preserved fossil remains suggest Carnotaurus could achieve speeds of approximately 25-30 mph (40-48 km/h), placing it among the fastest large theropods. Their vertebral column showed adaptations that increased body rigidity during running, while their lightweight skull with distinctive horn-like features reduced head weight without sacrificing predatory capabilities. These specialized running adaptations indicate Carnotaurus likely pursued fast-moving prey across the open plains of ancient Argentina, representing a different hunting strategy than many other large theropods.

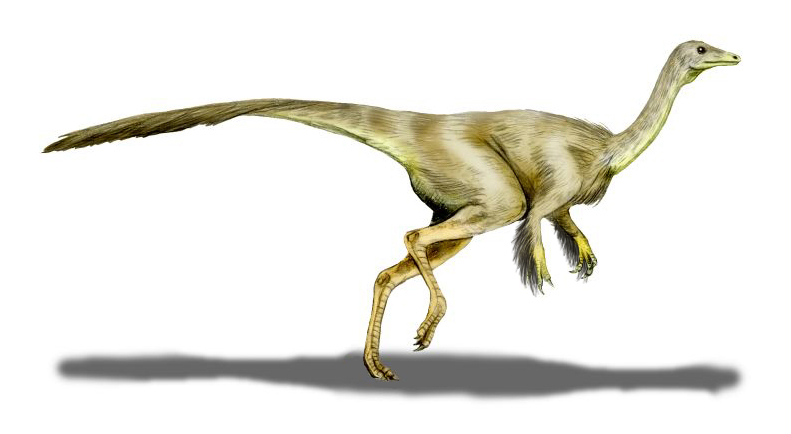

Dromiceiomimus: The Roadrunner of the Cretaceous

Dromiceiomimus epitomizes the ornithomimid family’s reputation for exceptional speed, with its name meaning “emu mimic.” This Late Cretaceous dinosaur possessed the classic ornithomimid body plan optimized for velocity: a small head, long neck, lightweight torso, and exceptionally elongated legs with adaptations for powerful running strides. Standing approximately 11 feet (3.5 meters) long, Dromiceiomimus had a particularly favorable weight-to-muscle ratio that facilitated rapid acceleration and high sustained speeds. Paleontological estimates suggest these dinosaurs could achieve velocities of 35-40 mph (56-64 km/h), rivaling modern ostriches and placing them among the fastest dinosaurs ever to exist. Their three-toed feet featured reduced digits that minimized ground contact area, decreasing friction during high-speed running across the ancient North American landscapes. As primarily herbivorous or omnivorous animals, Dromiceiomimus likely relied on this exceptional speed primarily to escape predators rather than to chase down prey.

Ornithomimus: Built Like a Modern Ostrich

Ornithomimus represents another standout member of the ornithomimid family with remarkable adaptations for high-velocity movement. With a body structure strikingly similar to modern ostriches, these Late Cretaceous dinosaurs featured the characteristic ornithomimid blueprint of long, powerful legs, a horizontal posture, and lightweight construction that facilitated exceptional speed. Growing to approximately 12 feet (3.7 meters) in length, Ornithomimus possessed proportionally some of the longest limbs among dinosaurs relative to their body size. Analysis of their fossilized leg bones suggests exceptional muscle attachment sites designed for powerful running strides. Scientific estimates place their top speed at approximately 30-35 mph (48-56 km/h), placing them in the upper echelon of dinosaur speedsters. Recent fossil discoveries have revealed that Ornithomimus possessed feathers, which would have further streamlined their bodies during high-speed running while also providing insulation and display functions. Their omnivorous diet and speed capabilities made them exceptionally successful animals in the Late Cretaceous ecosystems of North America.

Struthiomimus: The Speed-Adapted Omnivore

Struthiomimus exemplifies the ornithomimid family’s evolution toward high-velocity locomotion, with specialized adaptations that made it one of the Cretaceous period’s fastest runners. Measuring approximately 14 feet (4.3 meters) long, Struthiomimus possessed the classic ostrich-like body plan with notably long limbs that paleontologists estimate comprised nearly 40% of their total height. Their lightweight, hollow bones reduced overall mass while maintaining structural integrity during high-speed running. Biomechanical models suggest Struthiomimus could reach speeds of 30-35 mph (48-56 km/h), placing them among dinosauria’s elite runners. Their three-toed feet featured elongated metatarsals that effectively extended their leg length and stride capability, while their horizontal posture with counterbalancing tail created an ideal body configuration for rapid movement. As omnivores feeding on plants, small animals, and possibly eggs, Struthiomimus used their impressive speed primarily as a defensive adaptation, allowing them to escape the numerous large predators that shared their Late Cretaceous North American habitats.

Gigantoraptor: Surprisingly Fast for Its Size

Gigantoraptor represents a fascinating case study in dinosaur locomotion, combining enormous size with adaptations suggesting surprising speed capabilities. Despite weighing approximately 1.5-2 tons and standing about 17 feet (5 meters) tall, this unusual oviraptorosaurian dinosaur from Late Cretaceous Mongolia maintained many of the cursorial (running) adaptations seen in its smaller relatives. Their relatively lightweight construction featured hollow bones and possibly feathered covering, while their powerful hindlimbs showed specializations for efficient locomotion. Biomechanical analysis suggests Gigantoraptor could potentially reach speeds of 20-25 mph (32-40 km/h)—slower than the nimblest dinosaurs but remarkably fast for an animal of its substantial size. The combination of their unusually large stature with retained running adaptations indicates a unique evolutionary path, possibly allowing them to both intimidate potential predators and cover large territories in search of food resources. Gigantoraptor demonstrates how certain dinosaur lineages maintained impressive mobility even as they evolved toward larger body sizes.

Parasaurolophus: The Surprising Sprinter

Parasaurolophus defies the common assumption that large herbivorous dinosaurs were necessarily slow-moving, with evidence suggesting these distinctive crested hadrosaurs possessed impressive running capabilities. Despite their substantial size, growing to approximately 31 feet (9.5 meters) in length and weighing around 2.7 tons, paleontological analysis of their leg structure reveals adaptations for efficient locomotion. Their powerful hindlimbs featured well-developed muscle attachment sites and specialized joints that facilitated both walking and running gaits. Scientific estimates suggest Parasaurolophus could achieve short-burst speeds of approximately 19-25 mph (30-40 km/h), making them faster than many predators of comparable size. Their distinctive hollow cranial crest, while primarily evolved for sound production and display, may have also helped balance their body during rapid movement. This surprising speed capability would have provided Parasaurolophus with a crucial survival advantage, allowing family groups to flee from predators like Tyrannosaurus rex and Albertosaurus across the Late Cretaceous landscapes of North America.

Deinonychus: The Agile Pack Hunter

Deinonychus represents one of the most perfectly adapted predatory dinosaurs, combining moderate speed with exceptional agility and coordinated pack hunting behavior. These dromaeosaurids from Early Cretaceous North America measured approximately 11 feet (3.4 meters) long and weighed around 160 pounds (73 kg), with their lightweight frame supported by powerful hindlimbs. While not the absolute fastest dinosaurs in terms of raw speed—estimated at approximately 20-25 mph (32-40 km/h)—their true locomotive advantage came from remarkable maneuverability and acceleration. Their infamous “killing claw” on each foot required them to keep their weight off this specialized digit during running, resulting in a distinctive two-toed running posture that fossilized trackways have confirmed. Deinonychus likely employed a hunting strategy combining short, explosive bursts of speed with exceptional turning ability to outmaneuver prey rather than relying on sustained high-velocity pursuit. This locomotive state, paired with their pack hunting behavior, would have made them exceptionally efficient predators capable of taking down animals significantly larger than themselves.

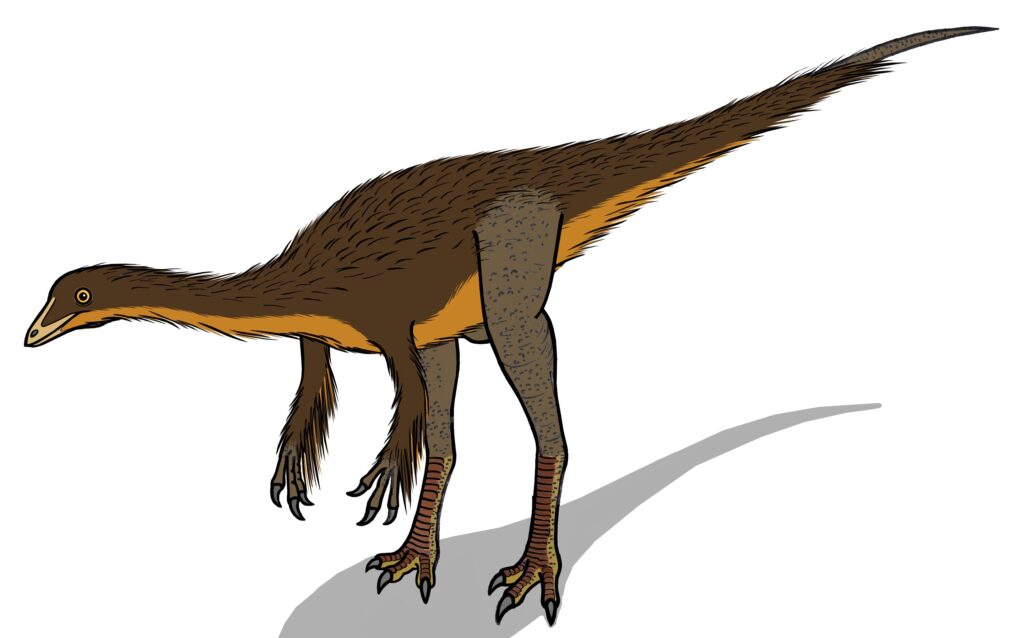

The Champion: Heterodontosaurus – The Unexpected Speed King

Perhaps the most surprising contender for the title of fastest dinosaur comes from an unexpected source: the diminutive Heterodontosaurus tucki from the Early Jurassic period. This dog-sized ornithischian dinosaur, measuring just 3 feet (1 meter) in length and weighing approximately 10 pounds (4.5 kg), possessed remarkable adaptations for high-speed movement despite not belonging to the typically swift theropod lineage. Recent biomechanical studies analyzing their perfectly proportioned hindlimbs, specialized hip structure, and lightweight frame suggest these small herbivores could potentially reach astonishing speeds of 40-45 mph (64-72 km/h) in short bursts. Their long, stiffened tail provided counterbalance during rapid locomotion, while their unusually diverse teeth (hence their name “different-toothed lizard”) allowed them to process plant material efficiently, fueling their high-energy movement. As small herbivores in an ecosystem filled with predators, Heterodontosaurus likely relied on this exceptional speed as their primary defense mechanism, allowing them to escape threats in the early dinosaur communities of southern Africa approximately 200 million years ago.

Honorable Mention: Microraptor – The Four-Winged Glider

While not technically a runner, Microraptor deserves special mention for pioneering an entirely different form of high-speed locomotion among dinosaurs. This remarkable four-winged dromaeosaurid from Early Cretaceous China, measuring just 2.5 feet (77 cm) in length and weighing only 2.2 pounds (1 kg), represents one of the most fascinating locomotor adaptations in dinosaur evolution. Exquisitely preserved fossils reveal Microraptor possessed flight feathers not only on its arms but also on its legs, creating a four-winged configuration that allowed for sophisticated aerial movement. While they could not achieve true powered flight like modern birds, biomechanical models suggest Microraptor was capable of exceptional gliding speeds, potentially exceeding 40 mph (64 km/h) when descending from trees. This unique locomotive strategy represents an important evolutionary experiment in dinosaurian mobility, potentially illustrating one pathway in the transition from ground-dwelling dinosaurs to fully flight-capable birds. Microraptor demonstrates that dinosaurs explored diverse solutions to the challenge of rapid movement beyond just running faster on the ground.

Evolution of Speed: Why Velocity Mattered in the Mesozoic

The remarkable range of locomotive capabilities across dinosaur species reflects the powerful evolutionary pressures that shaped these animals during their 165-million-year reign. Speed emerged as a critical